Japanese Cherry Blossoms Almost Didn't Make It to DC

Tourists often try to time their visits to Washington to coincide with the annual blooming of its famous cherry blossom trees along the Tidal Basin in April, and inevitably, someone tells them that the trees originally came from Japan as a gesture of international friendship. But the complete story is a bit more complicated, and includes plenty of odd twists and turns.

The saga starts in 1909, after William Howard Taft was sworn in as President. His wife, Helen Taft, had the ambition of hosting outdoor concerts in the Tidal Basin, in the days before the Jefferson and Lincoln memorials were built. But the area was fairly nondescript, and Mrs. Taft decided that it needed some decoration.

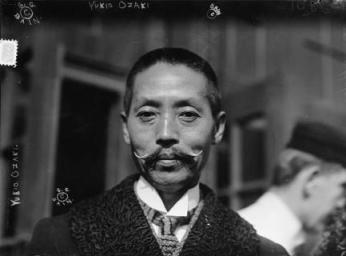

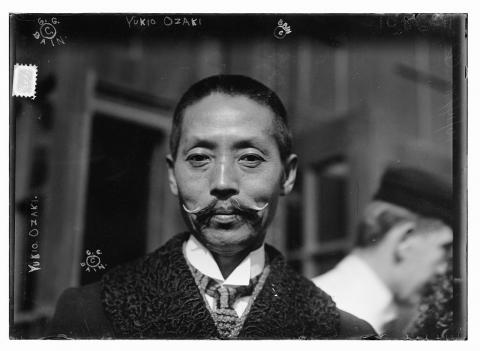

That's when Eliza Scidmore, a travel writer, and Agriculture Department official David Fairchild, who were both fans of Japanese cherry blossom trees, proposed to Mrs. Taft the idea of planting them in Washington. The First Lady, who'd been to Japan and seen the trees there, readily agreed. According to a 2012 essay by Japanese ambassador Ichiro Fujisaki, Japanese diplomats heard about the idea and then contacted Tokyo Mayor Yukio Ozaki, and suggested that he give some trees to the U.S. as a gift.

However, Ozaki — an ex-newspaperman and democracy advocate whose nickname was "The God of Constitutional Politics" — remembered the story a bit differently in his memoirs. Ozaki wrote that he felt warmly toward the U.S. because a powerful American financier, Jacob Schiff, had arranged for financing that enabled Japan to buy the munitions it used to defeat czarist Russia in the Russo-Japanese war of 1905. Ozaki claimed that it was he who first thought of presenting cherry trees to Washington in appreciation, but initially "kept my thought to myself," because he thought the Japanese government should be the one to make such a diplomatic gesture. But when the regime of his political rival Katsura Taro failed to think of it, Ozaki said he decided to act on his own after learning of Mrs. Taft's interest in planting cherry trees.

In October 1909, "I therefore proposed the idea to the city council as well as to the municipal assembly," both of which were in singular agreement," Ozaki wrote. "It was decided to present 3,000 young cherry trees of seven to eight feet in height, and experts were commissioned to take the necessary measures."

Apparently, the experts weren't quite diligent enough. After the trees were shipped across the Pacific they arrived in Seattle in December 1909. According to a 1909 Washington Post article, Col. Spencer Cosby, superintendent of public buildings and grounds in the District, wrote to Ozaki to convey "the hearty thanks of the government of the United States for your munificent gift, and the deep appreciation felt by its people." But U.S. Department of Agriculture inspectors promptly stopped the trees from being shipped across the country. "The trees were found to be infested with harmful insects and their eggs as well as various types of bacteria, and consequently, they all had to be destroyed," Ozaki wrote.

Ozaki recalls that a U.S. diplomat somberly gave him the bad news, probably expecting that Japan would be deeply offended. The mayor decided to break the tension by making a joke. "It has been an American tradition to desroy cherry trees since your first president, George Washington!" he exclaimed. "So there's nothing to worry about. In fact, you should be feeling proud!" It apparently worked, because Ozaki recalled that the official looked "very relieved" when he left.

Ozaki figured that the infestation had been a fluke, but when he went to replace the shipment, he learned, to his dispay, that "there was not a single field in the whole of Japan that had not been infested with pests or microbes. That was why trees grown in Japan usually to be drenched with toxins" — that is, insecticides.

In Ozaki's account, he got around that dilemma by asking Japan's Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce to grow cherry trees from seeds planted in special sterilized beds."

When the second batch of trees were finally grown, they again were shipped to the U.S., and this time, they passed inspection, Ozaki wrote.

On March 27, 1912, First Lady Helen Taft and Japanese ambassador Sutemi Chinda and his wife, Iwa planted the first cherry trees along the basin. As Ozaki marveled in his memoir, "Nowhere in Japan can one find such a concentration of three thousand trees in a single location. Not even in Yoshino are there so many."

Seventeen years later, Japan's Sakura-no-Kai, or Cherry Blossom Society, donated an additional 500 trees to replace some of the originals, which had ben destroyed by root rot after heavy rainfall during the summer of 1928.

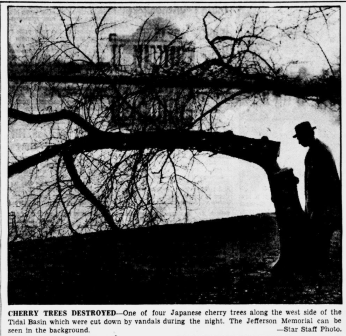

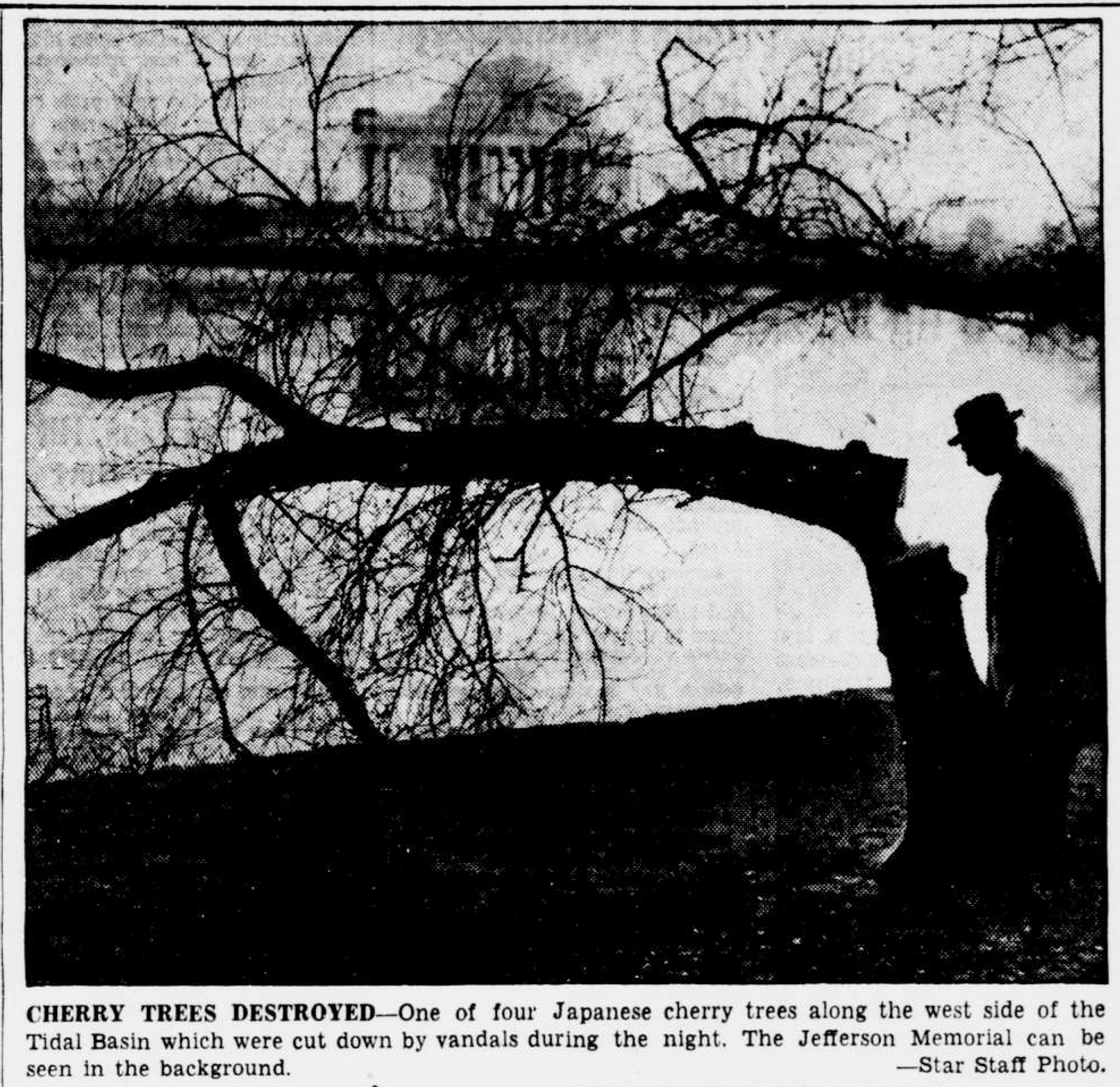

As a 2007 Washington Post profile of his daughter Yukika Sohma detailed, Ozaki's vehement opposition to the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 made him a marked man. Sohma recalled two truckloads of assassins pulling up outside their home, forcing the family to flee go into hiding. During World War II, according to Ozaki's memoir, Japanese newspapers reported that the trees had all been cut down, but the former mayor — by then, a member of the Japanese parliament — didn't believe it. "While the Americans must rightly have been angered by the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, I did not think that they would do such an insensitive thing," he wrote. He wasn't entirely right. Three days after the attack, vandals cut down four cherry trees, including two that had been donated by the Japanese.

He visited Washington in 1950, just four years before his death at age 95, and was photographed inspecting the blossoms.

Nevertheless, another diplomatic brouhaha occured in April 1965, after the postwar Japanese government offered Washington another 3,820 trees, as a gesture to recognize the strength of U.S.-Japanese ties, and to assist the First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson in her beautification campaign. To the embarrassment of Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall, who brokered the deal, Agriculture Secretary Orville L. Freeman refused to allow them into the country, citing a 1948 federal regulation blocking any importation of fruit trees. "Since then, no exceptions have been made to numerous requests," Freeman ruled. Eventually, the U.S. and Japanese governments quietly worked out a deal in which the Japanese donated trees of the same single-petal variety, but which had been grown in New Jersey.

In March 2012, First Lady Michelle Obama served as the stand-in for Mrs. Taft at a reenactment to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the planting of the cherry trees. According to Washington Post gardening columnist Adrian Higgins, only a few of the original trees still remain — "typically gnarled and misshapen specimens near the stone Japanese Lantern on the north side of the Tidal Basin."

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)