The Rise and Fall of Sisterfire, D.C.'s Women's Festival

“REAGAN EXPECTED TO CUT SPENDING FOR THE ARTS.” These eight words, the headline from the February 3, 1982 New York Times newspaper, turned the arts world in America upside down.1 If Reagan got his way, federal arts and humanities funding would be cut by up to 50%. Fear rippled through the community and arts organizations large and small began to grapple with the possibility of losing their funding.

Roadwork, a community-based, multiracial coalition of women arts activists in Washington, D.C, is one such group that had to reckon with these cuts to grassroots arts. Founded in 1978 by Amy Horowitz and Bernice Johnson Reagon, Roadwork served to “put women’s culture on the road,” build multi-racial coalitions, and inspire social change through the promotion and production of women in the arts.2 The organization produced concerts, tours, workshops, and rallies that highlighted women artists from varied backgrounds.

In the years leading up to the formation of Roadwork, women’s social and political activism had been on the rise, but the simultaneous cultural expansion being pushed forward by women was less acknowledged. The music and arts industries were no exception to the racism, sexism, and homophobia that permeated other aspects of society, and many artists who focused on women’s issues were dismissed by the general public, written off as feminists or lesbians.

Roadwork offered a different approach according to co-founder Amy Horowitz: “The women's movement was a backbone for giving voice to this expression, but it's also much broader. We embrace so many issues by virtue of the range of artists we represent and the range of their issues that we'll never neatly fit into any one movement. What we're embracing is the concept of coalition, in a very spiritual and political sense, the coalescing of people.”3 While many of the movements occurring at the time were happening parallel to each other, Roadwork wanted these movements to work with each other.

As the Roadwork team grappled with the funding cuts proposed by Reagan, it came up with the idea of a concert fundraiser that would amplify the work of grassroots artists while also helping to keep their non-profit activist arts organization afloat.4

Organizers rushed to make plans and the first Sisterfire festival took place on June 26,1982. D.C. Mayor Marion Barry declared the day “Women’s Cultural Day” in honor of the festival5 and 4,000 people flocked to Takoma Park Junior High School, where a stage had been set up outside. Tickets went for $13, with children 12 and under getting in for free.6 Festival attendees, dressed casually for the D.C. summer weather, gathered on the lawn.7

A volunteer in a white t-shirt that read “SISTERFIRE” in orange text across the chest kicked off the event with a declaration of Sisterfire’s purpose:

“We as women on this planet are aching for a voice. And that is why we have drawn you and gathered you all here together with us today to help in the creation of that voice. Sisterfire does not exist in a vacuum, it is in the voice of the song, it is in the pictures we draw, it is in the leap of the dance, and it is in the shout of the poem that we send forth, beyond the battle, our vision of the way the world should be.”8

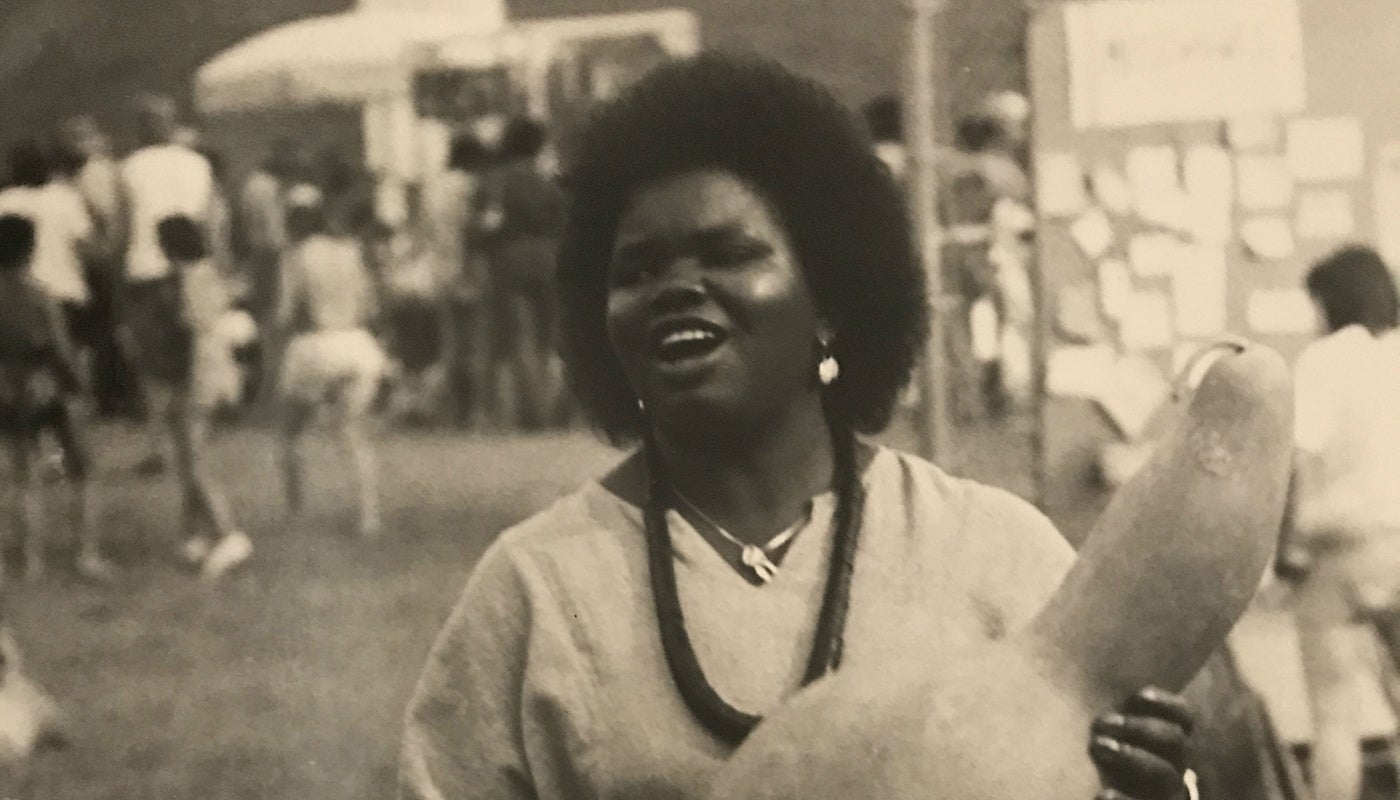

Festival-goers were then treated to performances by several acts at the forefront of the women’s music movement – all of whom donated their performances. Holly Near, Alexis De Veaux, Sweet Honey In The Rock, Michelle Parkerson, Retumba Con Pie, Women of the Calabash, The Harp Band, and Cris Williamson all performed and Margie Adam, who was in town working on an ERA concert at Constitution Hall, made a guest appearance.9

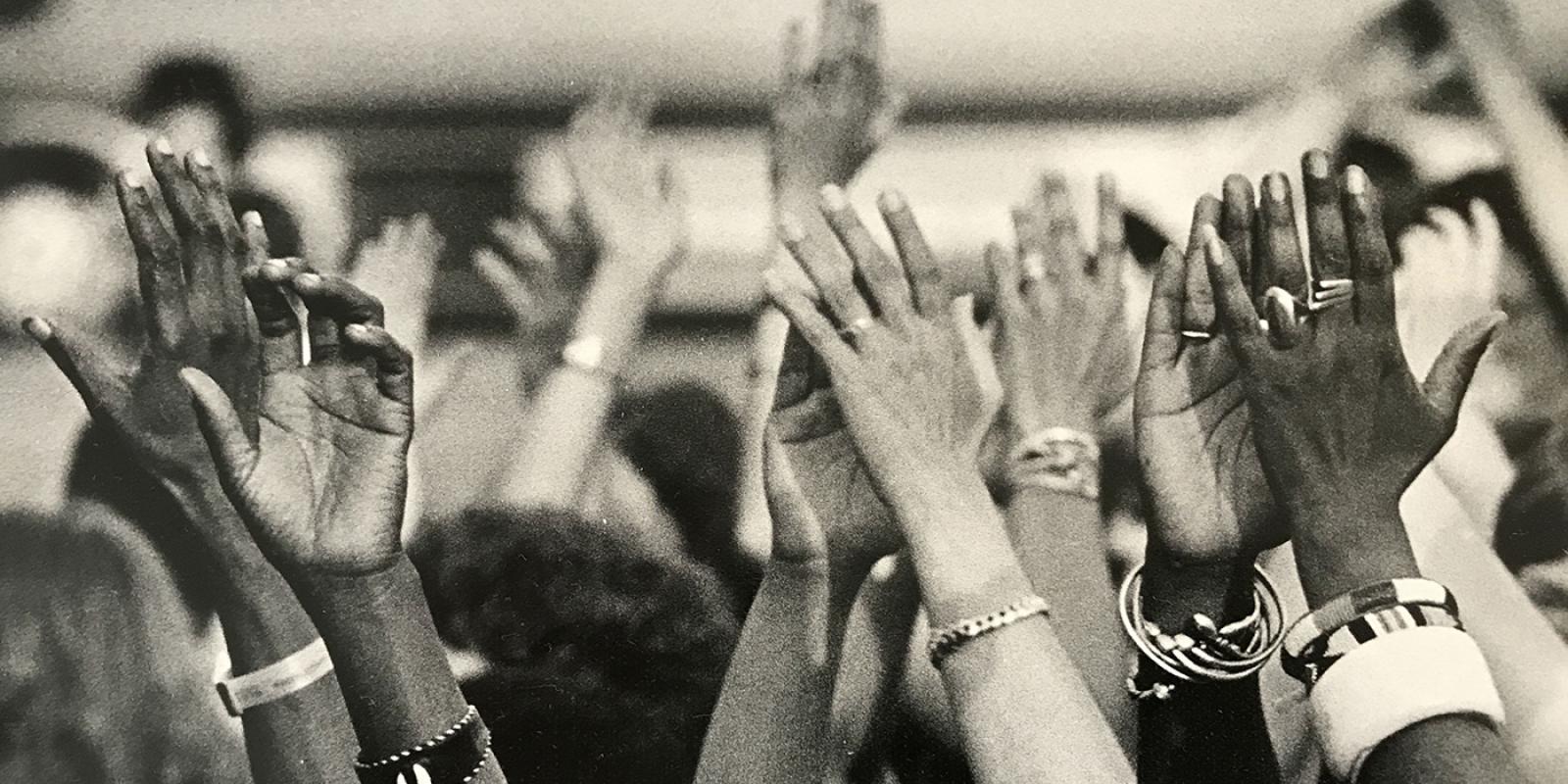

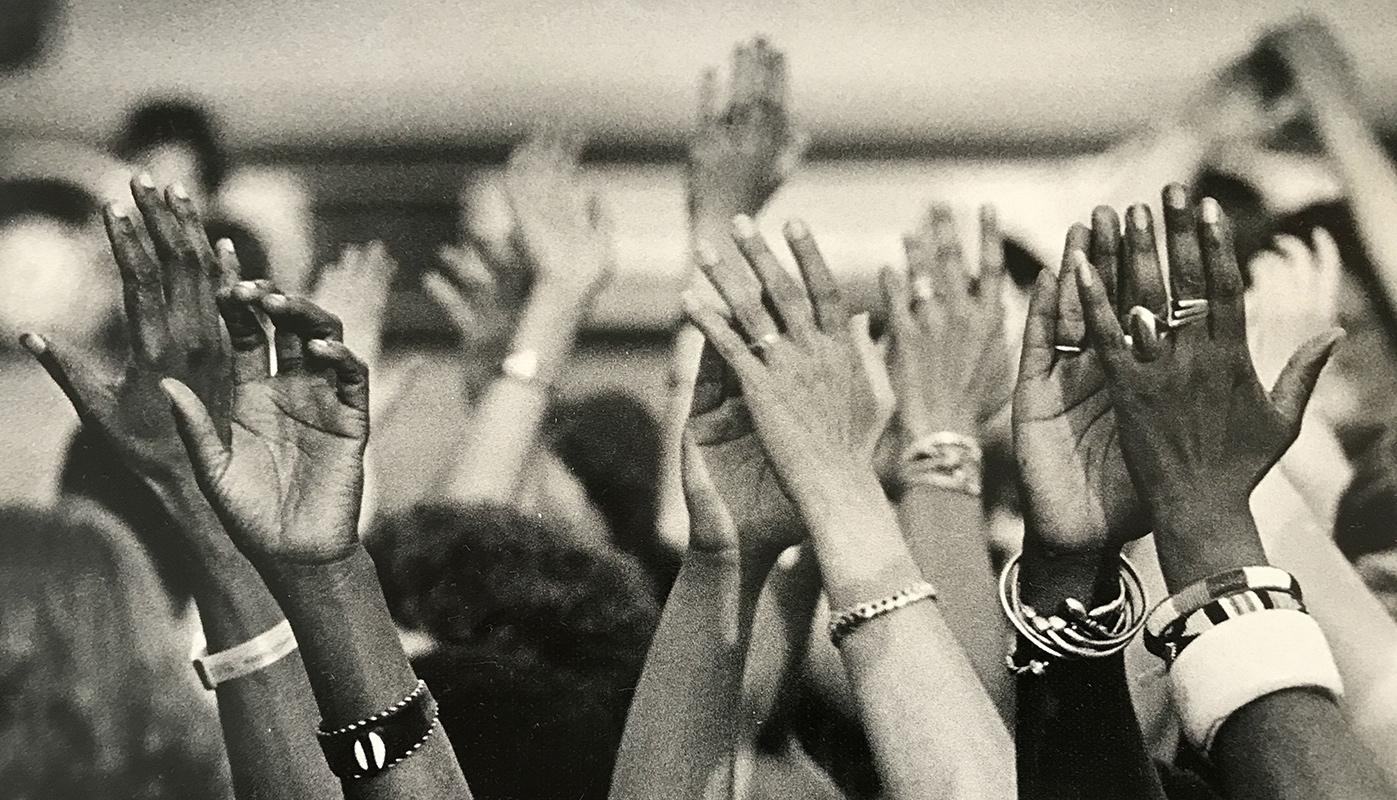

As the artists took to the stage, many attendees danced, chatted, and energetically sang. Others took jazz and Caribbean music and dance productions, poetry readings, food booths from around the world, and issue-oriented workshops on topics ranging from the environment to nuclear war to racial equality.10

Sisterfire encapsulated the Roadwork ethic: It was grounded in community, with 30 volunteers (known as Sistersparks) supporting the Roadwork crew during the first iteration of the festival (in later festivals there would be between 300 and 500 volunteers from all over the country)11, and it showed what a working model of multiracial coalition in an urban setting could look like.12

Buoyed by the success of the 1982 event, Roadwork turned Sisterfire into an annual festival.13 It grew from a one-day, one-stage event, to a two-day celebration of theatre, dance, poetry, music, and storytelling with a marketplace where artists could sell their goods. As it continued to expand, festival organizers catered it to the needs of a diverse audience. There were wheelchair accessible sections, sign language interpreters for every stage, and free childcare and children’s performers for festival-goers with kids. Additionally, Sisterfire constructed a stage dedicated to deaf artists where, in addition to hosting performances by deaf artists, they offered deaf women training in music production and performance.14

Sisterfire quickly became one of the largest women’s festivals in the United States.15 At the same time, however, it was not the “safe space” that other women’s festivals claimed to be – and that was by design. As Amy Horowitz told Hot Wire Journal in 1986, “it’s important for various groups to have safe spaces where it’s pretty homogenous and there’s a lot in common… Also, it’s important to have spaces where we move out of that safety, into a space that challenges us.”16 Sisterfire, according to Horowitz, was intended to be the latter. “There’s a cultural stretching going on for women. They’re going to hear things they may not be familiar with, that aren’t always comfortable and don’t always make sense to them.”17 In other words, Sisterfire was not just a women’s festival – it was a manifestation of Roadwork’s mission to create a multi-cultural coalition.

It was a big charge, and, as one might expect, there were tensions. Some white women complained that the Festival’s embracement of racially diverse music came at the expense of white women’s music. Meanwhile, some Black women complained that there were too many white women at the festival.18 And while Sisterfire was supposedly a festival that highlighted lesbians and lesbian musicians, one letter to Lesbian Connection magazine proclaimed that the festival “has clearly shown disdain for lesbians while profiting from lesbian money” and “lesbians finally got weary of supporting a festival where, almost without exception, lesbian visibility had been discouraged.” 19

Particularly controversial was the Festival’s decision to allow men. While other women’s festivals, such as the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, banned men from the premises, Sisterfire did not. In fact, organizers saw the inclusion of men as a strength: "What makes it real different is that it's designed to invite women and men to come and celebrate women's culture for a day," Horowitz told the Washington Post in 1982. 20 This was a source of criticism from some of the women who attended the event – which was advertised as an event by women and for women. As one frustrated attendee wrote to Lesbian Connection, “why can’t I go to a festival named ‘Sister’ and be with my sisters in women-only space?”21

Many of these tensions boiled over at the 1987 festival. Two white lesbian vendors were selling sculptures at a booth in the marketplace, and objected when two Black male volunteers approached the booth to view the art. As the vendors wrote later, the artist “gets her inspiration from womyn, and… does not choose to show her work to men.”22 Accounts of the incident vary, but one thing is certain: there was a physical altercation between the two male volunteers and the two female vendors. In the aftermath, the two vendors demanded that the men be banned from the festival going forward, but festival organizers balked at the suggestion as contrary to Sisterfire’s ethos.23 Upon review of the incident, they pointed to possible racial motivations as the root of the conflict: “We firmly believe that discrimination against men played a central role in initiating this incident and that racism played a role in escalating the exchange between the women and the men.”24

This clash turned out to be the beginning of the end of Sisterfire. As Horowitz recalled in a 2023 interview, “the festival went on for a few years after that, but we, at that point, couldn’t recover from that attack that we received from the radical lesbian separatist movement.”25 The last festival took place in 1989, but Roadwork continued to advance its mission to “put women’s culture on the road” in other ways.26

In 1991, Horowitz founded the Jerusalem Project, an ethnographic engagement among Israeli, Palestinian and US scholars and students, with the help of the Smithsonian Institution for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.27 This strengthened an already well-established relationship between the Smithsonian Folklife Center and Roadwork. Ralph Rinzler, co-founder of the Folklife Festival, was an early supporter of Roadwork and had provided them with their office space.28

The Sisterfire festival returned in July 2018 as a part of the Smithsonian Folklife Festival in celebration of Roadwork’s 40th anniversary. Artists represented by Roadwork took to the stage with performances of their music, poetry, and spoken word. The Folklife Festival has invited Roadwork back for the Sisterfire concert showcase every year since.29

Now over 40 years after the first Sisterfire festival in Takoma, the multicultural legacy of the event lives on. For Amy Horowitz, the amplification of non-white voices and the acknowledgment of racism within the women’s movement was one of the biggest ways that the festival was able to influence both the women’s movement and the wider cultural landscape. As she reflected to the Washington City Paper, “Sisterfire sent a message that racism is real within the women’s movement and within all the progressive structures that we were creating… we were born into a white supremacist structure, so unlearning is a lifetime commitment.”30

For others, like Alexis De Veux, a writer and attendee of the Sisterfire festivals, its impact looks forward. “The history and legacy of Sisterfire is poised to present women artists coming up behind us with a sense of —a model of—what is possible. That’s one of the things Sisterfire did. It made possible what had been impossible. And it can point the way to what can be done now.”31

Footnotes

- 1

Irvin Molotsky, “Reagan Expected to Cut Spending for the Arts,” The New York Times, February 3, 1982, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1982/02/03/199010.html?pageNumber=66.

- 2

“History of Roadwork Center,” Roadwork (blog), n.d., https://www.roadworkcenter.org/about/our-story/.

- 3

Richard Harrington, “Laying the Roadwork for Sisterfire,” The Washington Post, June 25, 1982, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1982/06/26/laying-the-roadwork-for-sisterfire/9ca29813-da27-4071-b5b4-1516b4344a96/.

- 4

Alona Wartofsky, “Sisterfire, a D.C. Women’s Festival From the ’80s, Is Being Resurrected This Weekend,” Washington City Paper (blog), July 6, 2018, https://washingtoncitypaper.com/article/324351/sisterfire-returns-for-smithsonian-folklife-festival/.

- 5

Anne Marie Welsh, “Sisterfire: A Dream Come True for Women Artists,” The Baltimore Sun, June 26, 1982, https://www.proquest.com/docview/537996680/abstract/A3D115BE1E134A03PQ/1?accountid=46320&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers.

- 6

Kay, “Sisterfire.”

- 7

Sisterfire - 1982, n.d., https://vimeo.com/195868964.

- 8

Sisterfire - 1982, n.d., https://vimeo.com/195868964.

- 9

Kay, “Sisterfire.”

- 10

Harrington, “Laying the Roadwork for Sisterfire.”

- 11

Nancy Seeger, “Sisterfire: Why Did Roadwork Skip 1986?,” Hotwire Journal, November 1986, https://hotwirejournal.com/pdf/hw_v2_n4.pdf.

- 12

Wartofsky, “Sisterfire, a D.C. Women’s Festival From the ’80s, Is Being Resurrected This Weekend,” https://washingtoncitypaper.com/article/324351/sisterfire-returns-for-smithsonian-folklife-festival/.

- 13

Sisterfire ran from 1982-1989, excluding 1986 when, due to internal and external concerns, the festival was not held.

- 14

“Sisterfire,” Blog, Wearing Gay History (blog), https://wearinggayhistory.com/exhibits/show/lesbiancapital/sisterfire#ref1.

- 15

Seeger, “Sisterfire: Why Did Roadwork Skip 1986?”

- 16

Rena Yount, “Roadwork: Putting Women’s Culture on the Road,” Hotwire Journal, March 1986, https://hotwirejournal.com/pdf/hw_v2_n2.pdf.

- 17

Rena Yount, “Roadwork: Putting Women’s Culture on the Road."

- 18

“Sisterfire,” Wearing Gay History.

- 19

"Responses,” Lesbian Connection, August 1989, p.18, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.28039233.

- 20

Harrington, “Laying the Roadwork for Sisterfire.”

- 21

"Responses,” Lesbian Connection, June 1988, p.10, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.28039226.

- 22

Lin Daniels and Myriam Fougere, “Violence Against Lesbian at Sisterfire,” Off Our Backs 17, no. 9 (October 1987), https://amyhorowitz.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Market-place-incident.pdf.

- 23

“Roadwork Responds...,” Off Our Backs 17, no. 9 (October 1987), https://amyhorowitz.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Sisterfire-Marketplace-response-1.pdf.

- 24

“Roadwork Responds...,” Off Our Backs.

- 25

Winter Hawk, “Roadwork Reflects on Its Herstory to Plan Its Future,” News Is Out (blog), March 21, 2023, https://newsisout.com/2023/03/roadwork-reflects-on-its-herstory-to-plan-its-future/12121/.

- 26

“History of Roadwork Center,” Roadwork (blog), n.d., https://www.roadworkcenter.org/about/our-story/.

- 27

Hawk, “Roadwork Reflects on Its Herstory to Plan Its Future.”

- 28

“Sisterfire: Roadwork 40th Anniversary Concert,” n.d., https://festival.si.edu/2018/sisterfire.

- 29

Hawk, “Roadwork Reflects on Its Herstory to Plan Its Future.”

- 30

Wartofsky, “Sisterfire, a D.C. Women’s Festival From the ’80s, Is Being Resurrected This Weekend.”

- 31

Alexis De Veaux, “Sisterfire Festival,” Blog, Alexis De Veaux (blog), n.d., http://alexisdeveaux.com/tag/sisterfire-festival/.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)