“Those Ladies Were Outraged”: A Lesbian Collective on Capitol Hill Shakes Up Feminism

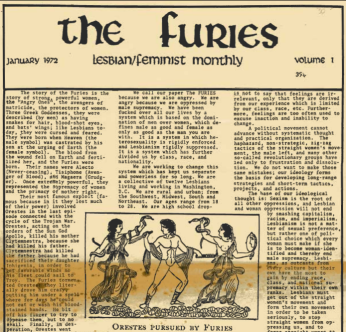

Splayed across the front page of the inaugural issue of The Furies newspaper in January, 1972, was an article that served as both an introduction and a call to arms. Speaking for her twelve-woman collective of the same name, the author, Ginny Berson, recounted the Greek myth of Orestes. The prince, having murdered his mother, flees from the relentless pursuit of the Furies: livid goddesses of vengeance and justice.

“We call our paper The FURIES because we are also angry,” Berson wrote. “We are angry because we are oppressed by male supremacy.” These women were tired of living within a “system which is based on the domination of men over women, which defines male as good and female only as good as the man [she is] with.”1

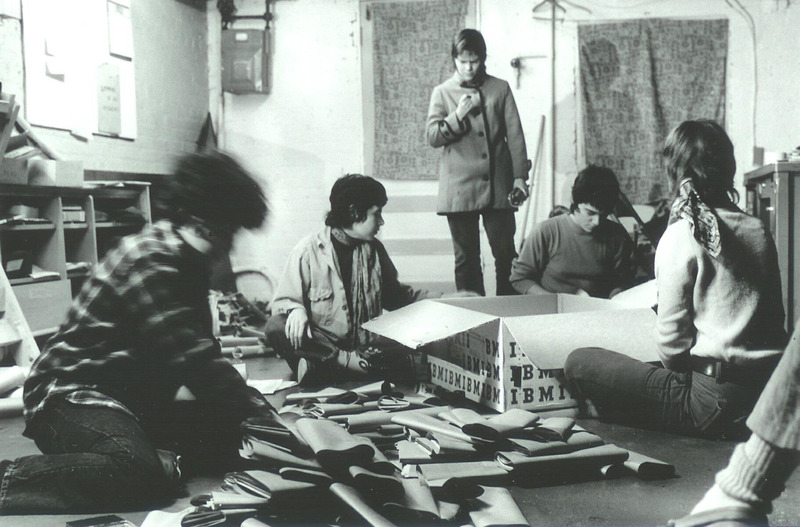

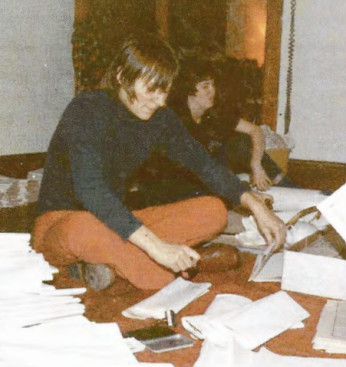

Ginny Berston wrote these words in a townhouse on 11th St SE, just south of Lincoln Park in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Washington, D.C. In the basement of the two-story house, she and eleven other women assembled their monthly newspaper, one part of their activities as a local lesbian separatist collective. The Furies were small and short lived—active only from 1971 to 1972—but the members, their radical ideas, and insistence creating room for lesbians within the feminist movement made waves long after the collective fell apart.

The women who would eventually become the Furies came from varying backgrounds: they were all lesbians, in their late teens to late twenties, from working- and middle-class families. They had experience in the turbulent world of social activism in the 60s, and most had already lived in feminist collectives.

“Anybody who was anybody lived in a collective or a commune then,” recalled ex-Fury Rita Mae Brown in her memoir.2

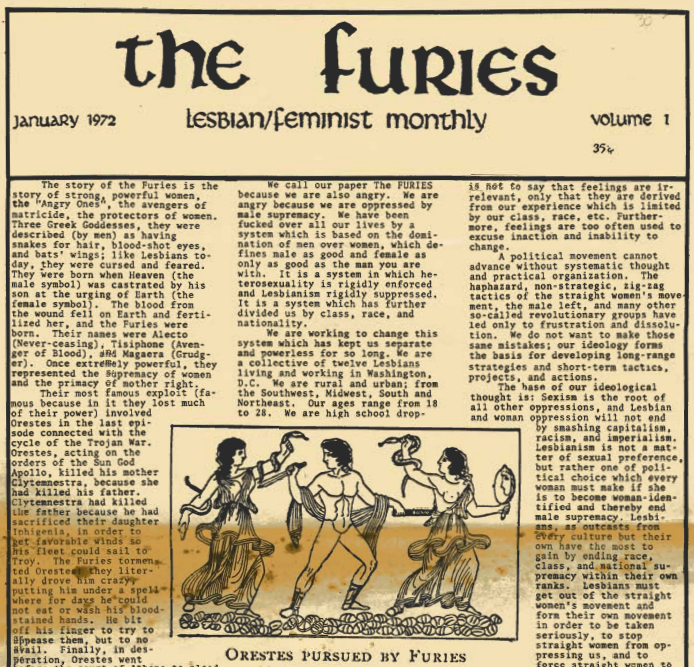

By 1970, several future Furies had already banded together, creating the Women’s Skills Center on California St. NW to teach women about home repair and self-defense.3 The workers at a nearby feminist daycare derisively called them “those women,” and for a time that was their name—though they spoke it with pride, not disdain.4

In 1971, Those Women helped to publish a lesbian feminist issue of motive magazine. They were attracted to the possibilities of publishing articles that would help carve out a place for lesbians in the Women’s Liberation movement. At the time, the rights and issues of gay women were far on the fringes of even radical feminist platforms. One of the Furies later recalled, “It didn’t matter whether they were black or white, rich or poor, men or women, feminists or non-feminists; nobody wanted anything to do with gay people.”5

The women began discussing the possibility of publishing their own newspaper, which could represent their views and goals. Their vision was ambitious: the monthly paper would include “poetry, photography; survival ([information] on motorcycle repair, running away, etc.); news page—what gay women are doing around the country; ideological articles including reprints; general articles about the facts of lesbian oppression; listings of gay collectives, organizations, publications, services; articles about women’s sexuality.”6 They figured it would take a dozen people to publish it.

At the end of 1971, the collective expanded to twelve lesbians: Ginny Berson, Joan Biren, Rita Mae Brown, Charlotte Bunch, Sharon Deevey, Susan Hathaway, Helaine Harris, Nancy Myron, Tasha Peterson, Coletta Reid, Lee Schwing, and Jennifer Woodul. Three children—two infants and a four-year-old—also lived with them.7 Having changed its name to the Furies, the collective moved to the gay-friendly neighborhood of Barracks Row, into a house with room for “all the equipment we needed to publish a newspaper.”8

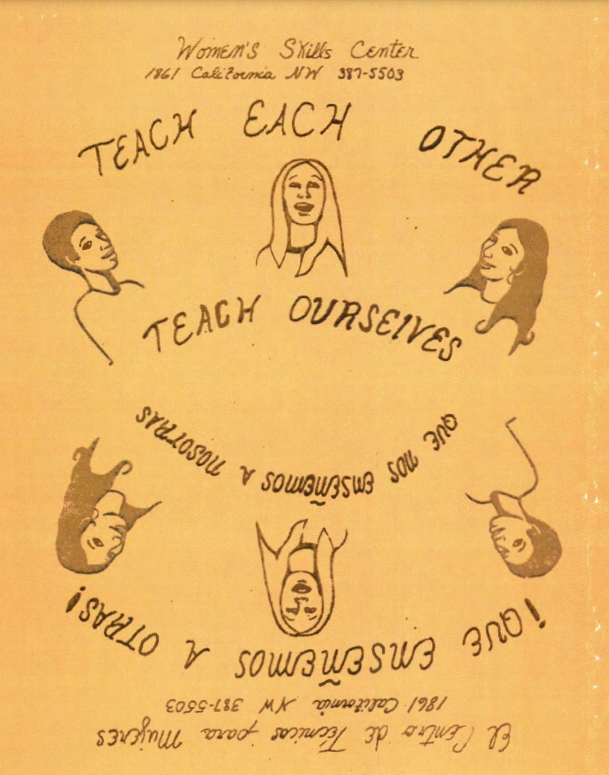

Patching the paper together on the chilly floor of their basement, the Furies published the first of ten issues of their newspaper in January, 1972. Theirs was the first serious lesbian collective in America (several Furies had previously been part of another lesbian collective in New York that lasted only a week). The women’s movement took notice—and not everyone was happy.

From the beginning, the ideology of the Furies was bound to cause a stir. The collective hailed from the radical branch of the feminist movement, which sought political and social change along with thorough personal transformation. They were interested in class conflict and racial inequality, as well as sexuality and women’s oppression.

The Furies saw feminism as a well of possibilities for creating a new and more equitable world, in which women would no longer be reliant on men—and in which the harms of imperialism, capitalism, and racism would cease, too. “We were patriotically motivated,” Rita Mae Brown wrote. The Furies were “dismayed, frightened, [and] disgusted” with America’s role in tragedies like the Vietnam War and the shooting of students at Kent State.9

The most contentious aspect of the Furies’ activism, however, was their position as lesbian separatists. In their newspaper, they explored lesbianism as a political, rather than biological, phenomenon. Developing their own feminist theory, the Furies argued that if heterosexual norms empowered the patriarchy, then straight women not only reinforced, but inherited male privilege through nuclear families and male partners. Sexual identity was socially constructed, they maintained, and just as all lesbians should be feminists, “all feminists must become Lesbians if they hope to end male supremacy.”10

In The Furies, Ginny Berson declared:

“Lesbianism is not a matter of sexual preference, but rather one of political choice which every woman must make if she is to become woman-identified and thereby end male supremacy... Whether consciously or not… the Lesbian has recognized that giving support and love to men over women perpetuates the system that oppresses her.”11

Other members phrased it more gently. Rejecting all male relationships would center the movement on women alone and allow them to develop their own ideologies. Political lesbianism was a form of radical growth and freedom, “to love women, and to take that love and nurture away from men completely, to only focus on ourselves and where we wanted to go.”12

At the most basic level, the Furies argued that they had no choice but to separate themselves from society because neither men nor straight women took them seriously. They had no place to exist.

The Furies’ positions “shocked” much of the women’s movement. “I don’t think [conservative feminists] believed lesbians could be literate,” Rita Mae Brown recalled humorously. “Those ladies were outraged.”13

Criticisms and debate poured in from other feminist groups, wary of hierarchies and the role of national ideological leadership the Furies were attempting to forge. The Furies were too elitist, too anti-male, too insular, unyielding to debate, or brutally focused on their singular ideology.14 The Furies addressed some of these criticisms, but largely turned inward to focus on their own projects.

The newspaper was not just a platform to discuss emerging lesbian ideology and theory, but also a means of communication. Its endpapers soon carried ads for women’s film and music festivals, feminist publishing houses, and women-owned businesses. It was also a beacon of visibility. Rita Mae Brown wrote that the Furies “alerted other gay women to the shattering knowledge that they weren’t alone. Today it’s almost impossible to feel the resonance of that connection.”15

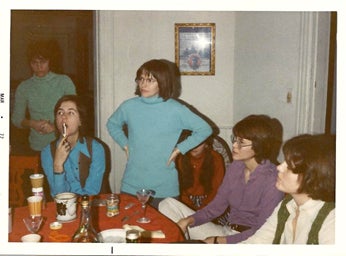

Beyond publishing the paper, the Furies found it imperative to put their ideas into practice. If the personal was political, then the political must also be made personal. To that end, they continued giving classes on California Street, coordinated public discussions and film screenings, and delivered theory workshops.

Living collectively in their Capitol Hill house was a key part of the Furies’ experimental feminist ideology. The little brick house was a political “laboratory where each member” could “overcome patterns of behavior that reflected both their class status and internalized hatred of women.”16 Their experiment of collective living would allow them to constantly exchange ideas and protect them from other activists who degraded their lesbian identities.

The Furies “rotated jobs in the outside world,” never working full-time “so more time would be put into Furies projects.”17 There was always something to do, whether that was writing articles, canvassing at local gay bars, or teaching at the Women’s Skills Center. Classes were given in English and Spanish, and the Furies struggled to stay ahead of their students: Joan Biren taught herself electrical wiring just before teaching a class on it.18

Members might arrive home to find a study group spread over the living room. In Coletta Reid’s history group, “we read materials from the Russian and Chinese revolutions,” as well as social and political theorists “Frantz Fanon, Norman O. Brown, and Herbert Marcuse.”19 The women pooled their money and possessions together, sleeping on mattresses on the second floor and storing all their clothes together.

Rita Mae Brown even brought her cat, named Baby Jesus (who reportedly did not enjoy living in the twelve-person collective). Every night, Brown set a place for her at the dinner table, to the humor and annoyance of her housemates.20

Unfortunately, not all the living experiments were successful. Personal grievances and ideological differences made life in close quarters increasingly difficult. Disagreements had to be resolved collectively, often in meetings that extended well past midnight.

Everyone happily agreed to pool collective resources, but it was “how it got divided out that was the problem,” wrote Joan Biren. “Could we have individual toothbrushes? Everything was up for grabs. Nothing was assumed about anything and it was just exhausting to figure it all out.”

Other Furies also criticized Biren on her class consciousness—a thorny ideological issue within the collective that was never resolved. Her graduate degree in political science from Oxford could have made her a valuable contributor on the subject for the newspaper. But other members argued that her elite education “trained her to verbally take advantage of others.” She was told to “develop modes of communication free from such ‘patriarchal taint’.” As a result, Biren became the paper’s photographer.21

The presence of the three children also caused disagreement. Childcare was a shared responsibility, and some members thought that it took away valuable time for activism. Rita Mae Brown was a vocal opponent of their presence, not only because the Furies were a political, not familial, venture, but because she “never trusted that we would be physically safe” in the house. Eventually, the children and their mothers were the first to leave the collective.

Brown left soon afterward, citing a laundry list of complaints, not least that the women (including herself) had failed to be “emotionally open” with one another, but that the duties of keeping the collective afloat had stretched them all thin. She “worked all the time” and had “no personal life”; there was no escape from the increasingly strained relationships inside the house. For Brown, the collective came to “[keep] the language of the revolution but the procedure of the Inquisition.”22 23

Under those conditions, it is unsurprising that the remaining women parted ways in the summer of 1972.

Their newspaper limped on for another year—a rotating, patchwork staff assembled editions from new contributors. The focus remained on lesbian issues but shifted away from separatism to building feminist institutions within society.24 The original Furies went their separate ways to become writers, artists, scholars, and activists for the women’s movement and other causes.

However, their intellectual contributions to the women’s movement far outlasted their collective. The Furies did not merely lead the debate over lesbians’ place and role in the feminist movement: they created it entirely. The Furies’ ideas—on sexuality, relationships, and identity—inspired debate throughout the twentieth century and remain relevant as examples of early lesbian and feminist theory. In recognition of those contributions, in 2016 the Furies’ house on 11th St SE became the first lesbian site on the National Historic Register.25

Looking back, collective member Coletta Reid summarized their intellectual legacy, taking the successes with the struggles: “The Furies should be remembered for developing a theory of lesbian-feminism… Through discussion, conflict and interaction, members were able to come to a holistic understanding of oppression which is now called intersectionality.”26

“We thought we were changing the world,” said Rita Mae Brown, then many years removed from her time writing articles and setting type in a basement on Capitol Hill. “I don’t know if we did that but we changed ourselves.”27

Footnotes

- 1

Berson, Ginny. “The Furies.” The Furies Vol. 1, January 1972.

- 2

Brown, Rita Mae. Rita Will: Memoir of a Literary Rabble-Rouser. Bantam, 2009.

- 3

The Furies Collective. “The Furies Collective – Challenging Notions of Separatist Space.” Accessed June 13, 2024.

- 4

National Register of Historic Places, Furies Collective, Washington, District of Columbia, Ref. #16000211.

- 5

Rhodes, Jacqueline. “Once a Fury (2020) - Trailer.” Video. YouTube, December 11, 2021.

- 6

National Register of Historic Places, Furies Collective, Washington, District of Columbia, Ref. #16000211.

- 7

The Rainbow History Proejcts. “The Furies.” Accessed June 13, 2024.

- 8

National Register of Historic Places, Furies Collective, Washington, District of Columbia, Ref. #16000211.

- 9 Brown, Rita Mae. Rita Will: Memoir of a Literary Rabble-Rouser. Bantam, 2009.

- 10 Valk, Anne. Radical Sisters: Second-Wave Feminism and Black Liberation in Washington, D.C. pp. 142–143

- 11 Berson, Ginny. “The Furies.” The Furies Vol. 1, January 1972.

- 12

Rhodes, Jacqueline. “Once a Fury (2020) - Trailer.” Video. YouTube, December 11, 2021.

- 13 Brown, Rita Mae. Rita Will: Memoir of a Literary Rabble-Rouser. Bantam, 2009.

- 14

Valk, Anne M. “Living a Feminist Lifestyle: The Intersection of Theory and Action in a Lesbian Feminist Collective.” Feminist Studies 28, no. 2 (2002): 303–32.

- 15 Brown, Rita Mae. Rita Will: Memoir of a Literary Rabble-Rouser. Bantam, 2009.

- 16

Valk, Anne M. “Living a Feminist Lifestyle: The Intersection of Theory and Action in a Lesbian Feminist Collective.” Feminist Studies 28, no. 2 (2002): 303–32.

- 17 Brown, Rita Mae. A Plain Brown Rapper. Oakland, CA: Diana Press, 1976.

- 18

National Register of Historic Places, Furies Collective, Washington, District of Columbia, Ref. #16000211.

- 19

National Register of Historic Places, Furies Collective, Washington, District of Columbia, Ref. #16000211.

- 20 Brown, Rita Mae. Rita Will: Memoir of a Literary Rabble-Rouser. Bantam, 2009.

- 21

Valk, Anne M. “Living a Feminist Lifestyle: The Intersection of Theory and Action in a Lesbian Feminist Collective.” Feminist Studies 28, no. 2 (2002): 303–32.

- 22 Brown, Rita Mae. A Plain Brown Rapper. Oakland, CA: Diana Press, 1976.

- 23 Brown, Rita Mae. Rita Will: Memoir of a Literary Rabble-Rouser. Bantam, 2009.

- 24

National Register of Historic Places, Furies Collective, Washington, District of Columbia, Ref. #16000211.

- 25

Riley, John. “Furies Collective Becomes First Lesbian Site on National Register.” Metro Weekly, May 6, 2016.

- 26

National Register of Historic Places, Furies Collective, Washington, District of Columbia, Ref. #16000211.

- 27 Brown, Rita Mae. A Plain Brown Rapper. Oakland, CA: Diana Press, 1976.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)