“Burnt All Their Houses”: Mount Vernon Narrowly Escaped British Destruction During the Revolutionary War

As the summer of 1781 drew near, the situation on Chesapeake Bay and its waterways looked bleak for American revolutionaries. English warships “move[d] with impunity” through the Bay and commanded total control of the water. Virginia could organize little resistance, since the Continental Army was elsewhere. Orders from the British naval command gave captains “liberty to… destro[y] the enemy’s public stores and magazines” wherever they could.1

On one April evening, some ten miles south of Alexandria, a handful of British warships weighed anchor on the Maryland side of the Potomac, setting fire to plantation houses and outbuildings, slaughtering livestock and plundering stores. The clamor of shouts and gunfire drifted over the river.

Watching from Mount Vernon, a member of the Washington family watched smoke curl into the darkening sky with a deep-seated sense of worry. General Washington’s home was well-known and undefended. Would it be the British ships’ next target?

Watching the plantations burn that afternoon was Lund Washington, a distant cousin of George who had been caretaker of Mount Vernon for six years. While George Washington was commanding revolutionary troops, Lund's tasks were to manage the plantation and act to protect Martha and the Washington grandchildren should danger arise.

Until April of 1781, though, the Potomac had been quiet. British and American Tory privateers in light vessels had periodically forced small skirmishes with landowners along the river, but never to much effect. The Royal Navy had mustered its forces elsewhere.

But the tides of the war were changing. Washington and Rochambeau made bold plans to attack the British in Virginia, sailing troops through the Chesapeake. To cut the American forces off, the English flooded the Bay with warships. When Lafayette was dispatched to march troops south over land instead, the Royal Navy ordered half a dozen ships to meet them where they would have to cross the Potomac.

Up the usually quiet river came three ships, two brigs, and two schooners. They accompanied the British warship Savage, commanded by Captain Thomas Graves and armed with sixteen cannons. Captain Graves was ordered to take advantage of favorable winds to sail upriver, burn Alexandria, and deal whatever damages they liked to American revolutionaries along the way. Mount Vernon now found itself in range of British firing orders.

The flotilla drew within sight of Alexandria on April 11. The county militia marched out to meet it, likely mustering at Jones Point. Luckily, they didn’t have to fire a shot: three of the ships ran aground in uncharted mudbanks.2 By the time Captain Graves freed them, the element of surprise was lost. Fearing American artillery, the ships retreated, seeking new targets along the Potomac.

The next day, Graves and his men pillaged several homes on the Maryland side of the river. They were about ten miles south of Alexandria and only “1/4 mile [from] General Washington’s house.”3 The flotilla demanded food and supplies from Maryland landowners. If they did not comply, raiding parties burned and destroyed their property. These clashes may have included the burning of American Major Henry Lyles’ plantation, resulting in a skirmish with militia.4 Either the night of the 12th or the morning of the 13th, Captain Graves turned his attention to Mount Vernon. Well aware to whom it belonged, he sent a “flag of truce” ashore to Lund Washington.5

George Washington had tasked his cousin with safekeeping two things: his family and his property. Luckily, Martha and the children were not at home, but Lund knew Mount Vernon stood no chance against the flotilla’s cannons.

Captain Graves sent a boat to ashore with the same demand for provisions and supplies he had made of the Marylanders, “with a menace of burning it… in case of a refusal.”6

Lund replied that Washington had “given him orders by no means to comply with any such demands, for that he would make no unworthy compromise with the enemy, and was ready to meet the fate of his neighbors.”7

This response did not please Graves, who ordered the Savage to move from the Maryland shore to Virginia’s, practically on Mount Vernon’s doorstep. He sent another message, summoning Lund on board.

Lund’s personal account of the incident is lost to history, so it is impossible to know what he was thinking. Back in October, he had written with blustering confidence about his ability to defend Mount Vernon from attack with only “fifty men well armed,” and that he had been assured an invasion by “shipping” was impossible.8 Under the eye of the English warships, that confidence was probably badly shaken. Without George or Martha Washington to consult, he had to make his own judgement call on how—or whether—to defend Mount Vernon.

Lund likely decided to try and save the plantation. He boarded the Savage with a willingness to compromise—and a platter of warm chicken as a gift. The mood onboard changed immediately. Graves received him “hospitably” and “expressed his personal respect” for George Washington’s character and Lund’s personal conduct.9

He apologized for the threat to burn Mount Vernon: apparently Lund’s response had caused the Captain to misunderstand his intentions, and he would never have “tak[en] the smallest measure offensive to so illustrious a character as the General.” As to the properties set aflame in Maryland, those had been the result of “provocations” by property owners.10

Historians have argued that Lund was swayed by flattery, impressed by Captain Graves’ etiquette, or simply moved by his compliments. It is also possible that he was simply being pragmatic, choosing to keep the plantation safe however necessary. Whatever the case, when he disembarked the Savage, he “instantly despatched sheep, hogs, and… other articles” to the enemy flotilla.11

Satisfied and resupplied, Captain Graves withdrew from Mount Vernon and continued his cruise of the Potomac. The flotilla would rejoin the main fleet in the Chesapeake, leaving charred homes and furious Americans behind. With Mount Vernon still standing and the ships’ sails receding in the distance, Lund Washington must have breathed a sigh of relief.

But if Lund had ensured Mount Vernon’s safety, he had endangered something else: George Washington’s reputation. Neighbors had lost their homes and livelihoods resisting the British, while Lund had not only saved his property, but willingly boarded the Savage with gifts.

When Lafayette learned of the incident, he wrote to Washington with concern. Lund’s choice as George’s representative “Will Certainly Have a Bad Effect, and Contrasts With Spirited Answers from Some Neighbours that Had their Houses Burnt Accordingly.”12

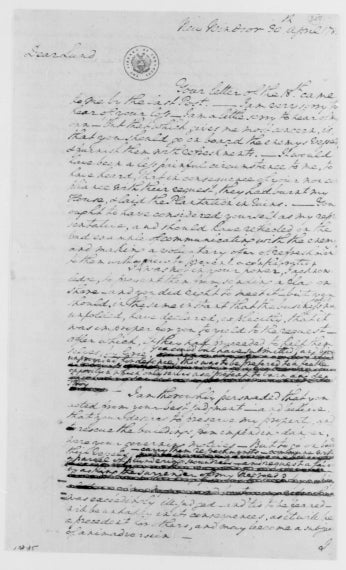

While Lund’s own report to his cousin is lost, but Washington deeply disapproved of his actions. In a letter, he wrote that Lund “ought to have… reflected on the bad example of communicating with the enemy, and making a voluntary offer of refreshment to them.”13

“It would have been a less painful circumstance to me,” George wrote, “To have heard, that in consequence of your non-compliance with their request, they had burnt my House, & laid the Plantation in ruins.” Though he thanked Lund for acting “from your best judgement” to preserve Mount Vernon, he reproached his decision to “commune with a parcel of plundering Scoundrels.”14

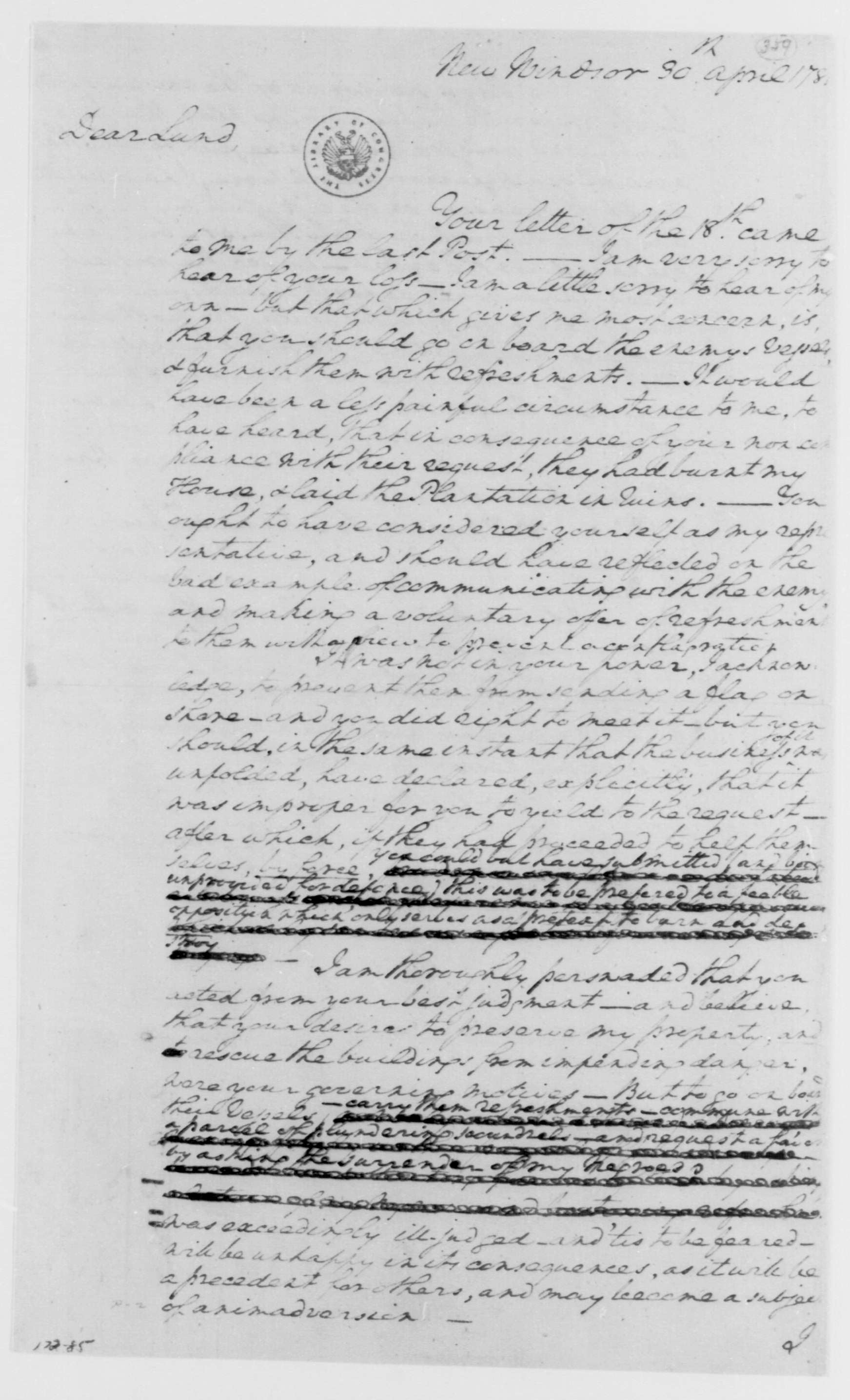

But the loss that most peeved Washington seemed to be the simultaneous escape of seventeen slaves, nearly 10% of Mount Vernon’s enslaved population.15 The British promised “Freedom to All… Slaves… being able to bear Arms” that escaped to English forces.16 Lund knew these individuals had taken refuge aboard the Savage. Perhaps he calculated that Graves might be more likely to return them in exchange for supplies and Lund’s cooperation. In any case, the Captain did not. The Savage carried slaves from Mount Vernon and other plantations along the Potomac to freedom.

Washington made “strenuous efforts” to recover these men and women after the war.17 Of the seventeen, seven were later recaptured in Philadelphia and Yorktown.18 The rest likely reached freedom in Canada, boarding English ships after Britain’s surrender later that year.

One of these slaves was a girl named Deborah, who was only eighteen years old when she escaped to the Savage. Sailing to the British naval base in Portsmouth, she later made her way to New York City. There, she married another escaped slave named Henry Squash.

When the Revolutionary War ended, the Treaty of Paris prohibited the British from “carrying away” Americans’ property, including slaves. The commander of the British evacuation, Sir Guy Carleton, refused to return escapees, saying that he would be “delivering them up some possibly to Execution and others to severe Punishment,” breaching England’s initial promise of freedom.19 Instead, he offered cash compensation to enslavers, which Washington reportedly accepted but never received.

Even after accepting compensation, he wrote to the commissioner of embarkation at New York, asking him to detain any of the Mount Vernon slaves: “If by Chance you should come at the knowledge of any of them, I will be much obliged by your securing them, so that I may obtain them again.”20

Luckily, Deborah had boarded a ship just the day before. With other freed slaves, she landed in Nova Scotia, likely in May of 1783. She settled in Birchtown, named for the British commander of New York who wrote the certificates of freedom for many American ex-slaves. She possibly remarried, and her death date is unknown, but she lived the rest of her life in freedom in Canada. Washington continued to own slaves until his death.

In the end, the survival of Mount Vernon was a brief smudge on Washington’s reputation, quickly forgotten about as the victorious General became the newborn nation’s first President. George Washington was not accused of traitorousness, nor did the incident split the Washington cousins. Lund would steward Mount Vernon for four more years without incident. George Washington wrote Lafayette that Lund acted more as “guardian of my property than… my honor” in dealing with Graves, which “plunged him into error.” But he had no question of the “integrety," which had led George to entrust “every species of my property to [Lund’s] care—without reservation, or fear of his abusing it.”21

Thanks to Lund, George Washington was able to retire to his beloved home overlooking the Potomac after his presidency. By acquiescing to the British once, an icon of American heritage was preserved for all Americans to come. Mount Vernon visitors today are indebted to Lund Washington and the other dedicated caretakers who shepherded George Washington’s home through hard times.

Footnotes

- 1

"BURNT ALL THEIR HOUSES" The Log of HMS Savage during a Raid up the Potomac River. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 99, no. 4 (1991): 513–30. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4249247?seq=1.

- 2

"BURNT ALL THEIR HOUSES"; see remarks for April 12.

- 3

"BURNT ALL THEIR HOUSES"; see remarks for April 12.

- 4

Schenawolf, Harry. “Mount Vernon Saved at Washington’s Embarrassment.” Revolutionary War Journal, February 27, 2025. https://revolutionarywarjournal.com/mount-vernon-saved-at-washingtons-embarrassment/.

- 5

"BURNT ALL THEIR HOUSES"; see remarks for April 12.

- 6

Washington, George to Washington, Lund, 30 April 1871, in NARA Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov/?q=%20Author%3A%22Washington%2C%20George%22%20Period%3A%22Revolutionary%20War%22%20lund&s=1111311113&r=115&sr=#GEWN-03-31-02-0415-fn-0002

- 7

Washington, George to Washington, Lund, 30 April 1871, in NARA Founders Online.

- 8

Hirschfeld, Fritz. “The British Raid on Mount Vernon.” Naval History 4, no. 4 (September 1990). https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/1990/september/british-raid-mount-vernon

- 9

See footnote in Washington, George to Washington, Lund, 30 April 1871, in NARA Founders Online.

- 10

See footnote in Washington, George to Washington, Lund, 30 April 1871, in NARA Founders Online.

- 11

See footnote in Washington, George to Washington, Lund, 30 April 1871, in NARA Founders Online.

- 12

Lafayette to Washington, George, 23 April 1871, in NARA Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-31-02-0354

- 13

Washington, George to Washington, Lund, 30 April 1871, in NARA Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov/?q=%20Author%3A%22Washington%2C%20George%22%20Period%3A%22Revolutionary%20War%22%20lund&s=1111311113&r=115&sr=

- 14

Washington, George to Washington, Lund, 30 April 1871, in NARA Founders Online.

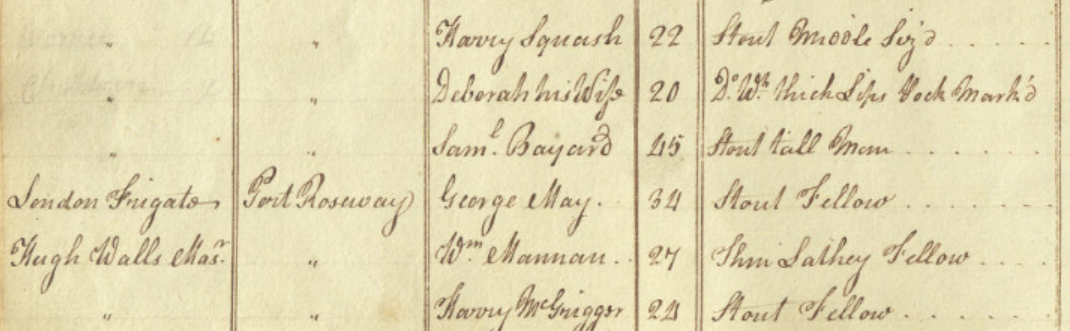

- 15

According to Lund’s recollection, the seventeen here: “Peter. an old man. Lewis. an old man. Frank. an old man. Frederick. a man about 45 years old; an overseer and valuable. Gunner. a man about 45 years old; valuable, a Brick maker. Harry. a man about 40 years old, valuable, a Horseler. Tom, a man about 20 years old, stout and Healthy. Sambo. a man about 20 years old, stout and Healthy. Thomas. a lad about 17 years old, House servant. Peter. a lad about 15 years old, very likely. Stephen. a man about 20 years old, a cooper by trade. James. a man about 25 years old, stout and Healthy. Watty. a man about 20 years old, by trade a weaver. Daniel. a man about 19 years old, very likely. Lucy. a woman about 20 years old. Esther. a woman about 18 years old. Deborah. a woman about 16 years old.” (See footnote in Washington, George to Washington, Lund, 30 April 1871, in NARA Founders Online.)

- 16

George Washington’s Mount Vernon. “H.M.S. Savage.” Accessed October 4, 2025. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/h-m-s-savage.

- 17

"BURNT ALL THEIR HOUSES" The Log of HMS Savage during a Raid up the Potomac River.

- 18

Their names were Frederick, Frank, Gunner, Sambo, Thomas, Lucy, and Esther. (See footnote in Washington, George to Washington, Lund, 30 April 1871, in NARA Founders Online.)

- 19

Gehred, Kathryn. “Escaping General Washington: The Story of Deborah Squash.” Washington Papers, December 15, 2017. https://washingtonpapers.org/escaping-general-washington-story-deborah-squash/.

- 20

Gehred, Kathryn. “Escaping General Washington: The Story of Deborah Squash.” Washington Papers, December 15, 2017. https://washingtonpapers.org/escaping-general-washington-story-deborah-squash/.

- 21

Washington, George to Major General Lafayette. 4 May 1781 in NARA Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-31-02-0453

![Newspaper advertisement for Ona Judge, runaway slave [Source: Encyclopedia Virginia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2024-05/Ona%20Judge%20-%20Runaway%20Ad.jpg?h=10a38b52&itok=0_-DEpCm)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)