“I Catered for the Best People”: Hattie Sewell, a Black D.C. Entrepreneur in Rock Creek Park

If you enter Rock Creek Park on Tilden Street, you will find Peirce Mill: a quaint stone building with a water wheel paddling in a small stream off Rock Creek. Today, the Mill has been restored by the National Park Service, who use the building to educate visitors about D.C.’s agricultural beginnings.

But more than a century ago, the building had served a different purpose entirely: it had been transformed into a tea house, where families and park visitors could enjoy light meals and refreshments in a quaint, rustic atmosphere.

The mill was constructed in 1829, as part of the Peirce family’s estate. The property was incorporated into Rock Creek Park in 1890, and when the mill became inoperable, park managers set about improving the site, adding a dam and restoring the building.1 Rock Creek was managed by the US Army Corps of Engineers, who leased the Teahouse to civilians to run its business.

In the autumn of 1919, the director of Rock Creek Park, Colonel Clarence S. Ridley, was getting anxious. He desperately needed a new tenant to take over the teashop.

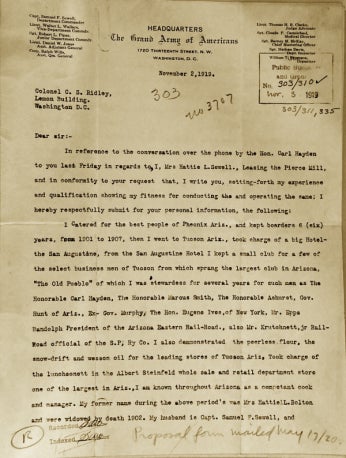

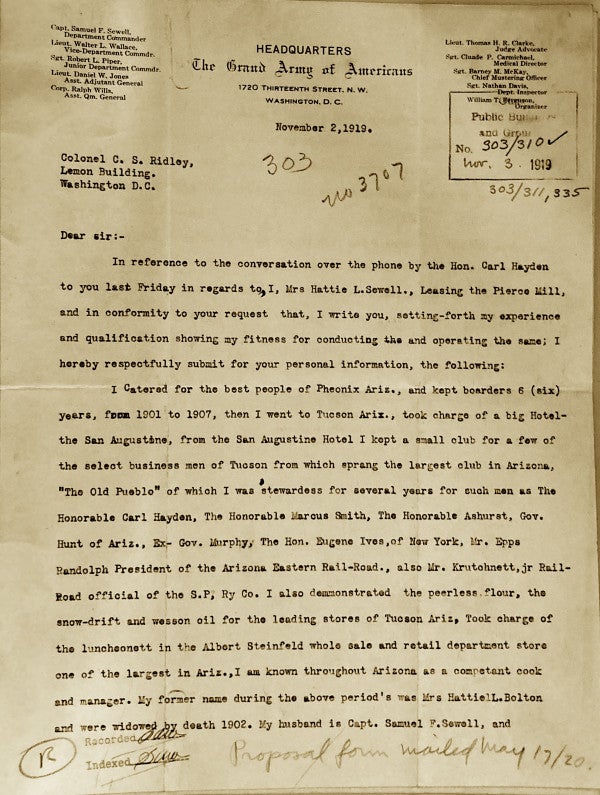

Out of many applications, this one looked promising. In typewritten script under heavy Gothic letterhead, the applicant wrote “setting-forth my experience and qualification showing my fitness for conducting and operating” the Teahouse.

The applicant’s experienced included managing department store “lunchonett[es]” and caring for boarders. They “catered for the best people of Phoenix Ariz[ona]” and they were the “stewardess” of the “largest club in Arizona,” whose membership included a railroad president, current and former state governors, and US congressmen.

“I am known throughout Arizona as a competent cook and manager,” the letter-writer boasted. They promised to “make quite a few profitable changes… in addition to making… the resort attractive and… improve [its] value.”2

The letter was signed by Hattie Sewell, a Black woman and entrepreneur who had only recently moved to Washington. In his office, Colonel Ridley’s interest was piqued.

Hattie Sewell was born Hattie Ridley in Dallas, Texas around 1883.3 She and her mother Rena were domestic servants: at only 10 years old, Hattie was already a maid and nanny.

But in her teens, Hattie would form part of the Great Migration, in which six million African Americans moved away from the South to “escape stifling segregation and find new economic opportunities.”4 The Ridleys relocated to Arizona, joining the state’s small African American population.

There, Hattie’s station began to improve, both by good fortune and her own industrious nature. She married J.W. Bolton, one of the city’s few Black businessmen, and together they lived in a mostly white neighborhood. After Bolton died in 1902, Hattie raised her only son, Chauncey, on her own. She ensured received a fine education: he was the only Black student in his school.5

She also began working herself, accumulating the significant hospitality experience she enumerated in her letter to Col. Ridley.

Hattie’s timing was impeccable. She had orchestrated a favor from one of her former customers, now a congressman. Arizona Representative Carl Hayden telephoned Ridley to recommend Mrs. Sewell for the teahouse contract.6 Not long after, Hattie’s letter arrived.

In addition, Col. Ridley badly needed a new manager. The previous tenant, Florence Blake, had been removed for “glaring incompetence.”7 She was bad-tempered, owed servers back pay, and was infamous for her “poor service, exorbitant prices, and poor standing” with vendors. She was also likely illegally selling alcohol, leaving behind “a great amount of trash” and “[t]wo hundred fifty-six empty whiskey bottles” when she vacated the teahouse.8

He received only a few other serious proposals: a higher bidder withdrew her offer and the other woman wanted to rent well below the market rate.9 Sewell offered a moderate $45 in rent and was also the only one to submit a formal proposal, with a menu and plans for “up to date… waiters, and first class cooks.”10

The civilian superintendent of the park interviewed her, and wrote approvingly to Ridley: Hattie “impresse[d] me as being a thorough business woman capable of rendering first-class service.” All her references spoke “very highly of her honesty and integrity and all stated that she will be a satisfactory” concessioner.11

Ridley wrote to Hattie soon after to let her know she had been selected for the contract.

This was exciting news. Only the year before, Hattie had moved to Washington with her new husband, Samuel Sewell. Sewell was a non-commissioned officer of the 10th US Cavalry (a Buffalo Soldier unit) and one of only 160 African American soldiers to earn the rank of Captain.12 A disabled veteran, he now headed a national advocacy organization for Black veterans of World War I: The Grand Army of Americans.

(Hattie penned her proposal to Ridley on the organization’s official letterhead, which included the Sewells’ address. The pomp couldn’t have hurt.)

The Sewells moved to 1720 13th Street NW, purchasing a home and taking on boarders.13 The vibrant African American community around U Street was much different than Arizona. The neighborhood boasted more than 300 Black-owned businesses, and jazz could be heard at all hours from cabarets and clubs.14 The first Black woman to earn her PhD would graduate within two years.15

At the same time, racism and oppression limited African Americans’ opportunities to succeed financially and socially. Race riots and white supremacist terrorism swept across the country in the “Red Summer” of 1919, exploding in D.C. in a four-day anti-Black riot which killed at least 15 people.16

Thus, when Hattie signed her 18-month lease in July 1920, she did so in an environment deeply prejudiced against her, but still glimmered with exciting new opportunities for African Americans.

She got to work without delay. Teahouses were “enormously popular” in the early 20th century, and Hattie set about making hers as homely as possible, with excellent service. Her menu offered soft drinks, refreshments, dinner options, cigars and cigarettes, candles, fruits, and hot waffles on Sunday mornings.17

In an advertisement, she called on Washingtonians to “hear the gentle ripples of the “Old Mill Stream” and enjoy the most beautiful garden-spot of any capital on earth.”18

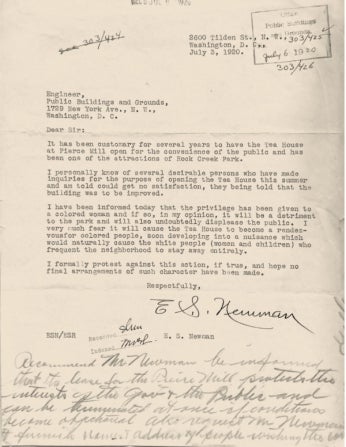

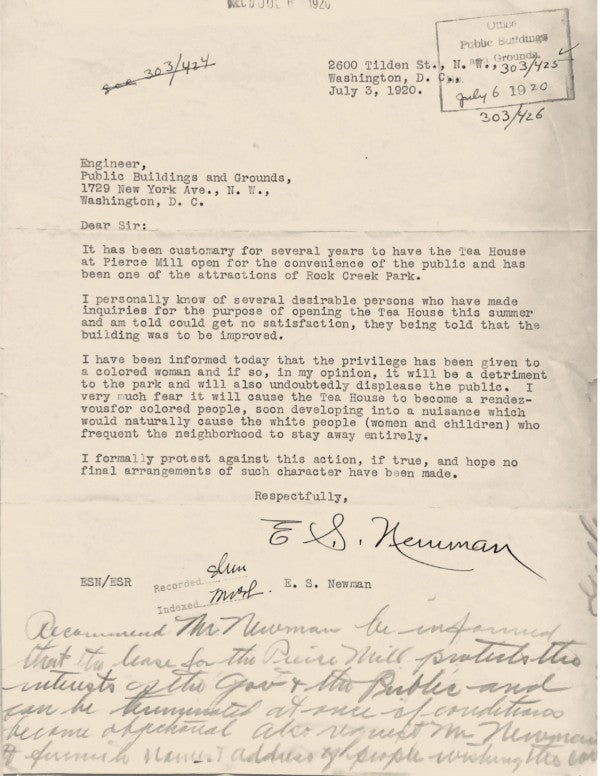

But almost immediately, there was a complaint. E.S. Newman, a neighbor and member of the Peirce family, wrote a delicately worded letter to Col. Ridley. He congratulated the Colonel on the reopening of the renovated building, but was writing to raise some ‘neighborly’ concerns about the proposed tenant.

He was worried that giving “the privilege” of the Teahouse contract to “a colored woman” would be a “detriment to the park.” He feared “very much” that it would “cause the Tea House to become a rendezvous for colored people, soon developing into a nuisance which would naturally cause the white people… to stay away entirely.”19

Newman’s complaint was racist and baseless, but Park managers had a reason to stay in his good graces: his mansion, Cloverdale, was just up the hill from the Teahouse. Management had long wanted to purchase the property to incorporate into the park and therefore wanted to avoid offending the man who might sell it to them.

In response, Ridley diplomatically wrote that the government could end the lease if “conditions become objectionable.”20 To this day, no other complaints have been found.

But Newman continued badgering Park leaders about Sewell’s proprietorship. His letters continued, and June 1921, he wrote angrily that visitors were turning up “every day and every night… to use [his] house phone.”21

According to Newman, Park visitors were now prohibited from using the Teahouse phone and were sent up the hill to Cloverdale instead. Newman had recently leased the house to US Senator Medill McCormick and did not want his distinguished guest inconvenienced by the constant interruptions. He heavily implied that Hattie (as a Black woman) was the cause of it all.

“At the time the tea house was rented to these colored people I protested and advised your office that it would become a nuisance,” he wrote. “This condition now exists… and it is hoped that when the lease expires the place will be rented to an experienced white person.”22

But this was not the full story. When the park superintendent investigated the matter, he found that Newman’s story was “not founded upon facts.”

Hattie had told him that the only reason she sent visitors up to Cloverdale at all was because “Newman’s wife Clara had invited the teahouse staff to send anyone needing telephone service up the hill” to their property.

In fact, the superintendent discovered that, “conditions at the Mill” seemed “satisfactory to the Newmans until they were required to pay for the services rendered by the concessionaire [Hattie] instead of making a convenience of her.”23

All Hattie had done was ask that the Newmans pay for their food like any other visitor.

But leadership had changed in Rock Creek. The Harding Administration had replaced Col. Ridley with Lieutenant Colonel Clarence O. Sherrill. According to historian Eric Yellin, Sherrill was “an avid segregationist” and more willing to entertain Newman’s racist complaints.24

He immediately installed a new public payphone and apologized to Newman. Despite Hattie’s improvements to revenue and excellent rapport with customers and staff, he assured Newman that once her contract expired, “the matter of selecting a new concessionaire will be given consideration.”25

Therefore, when Sewell wrote in September 1921 to request a two-year extension of her lease, she was given an unexpected answer.

Park leaders had received no other complaints about the Teahouse. Business increased 200% during Sewell’s tenure and, interviewed patrons spoke “very highly of the treatment received and the quality of the food served.” By her own admission, Hattie had “conducted [her] business in accordance with all regulations.”26

Despite her sterling record, Sherrill decided to end Sewell’s tenure at Rock Creek. The Teahouse would be turned over to the War Department, who would use the revenue for charity work.

This must have left Hattie baffled, perhaps searching for a reason Sherrill could be dissatisfied with her work. But she wrote a graceful response, asking that her application be reconsidered should Sherrill return to a “competitive” bidding process.27

She left quietly in October, deciding not to stay on through the slow, cold winter season.

The War Department, perhaps surprised by Sherrill’s abrupt offer, walked back its commitments. To avoid making a public offer (in which Hattie could re-apply), Sherrill scrambled to find another willing charity: the Girl Scouts of Washington D.C.

When the new proprietors (all white women) reopened the Teahouse in November, Sherrill announced that “A delightful air of hospitality will be found… at the teahouse, as the management is directly under a large committee of ladies prominent in Washington society.”28

As a government representative, it was improper for Sherrill to “steer business toward a particular contractor” over others.29 He recognized as much, but was unwilling to allow any competition, because that was how a Black woman had been selected.

“It would be impossible to select or obtain… the type of proprietors desired” via an open bid, he wrote. The “desired proprietors” did not, apparently, include African Americans. Justifying Hattie’s removal, he wrote only that “a great many complaints were received and a large number of people stopped patronizing the place.”30 Both these excuses were lies.

Whether Hattie ever knew the true reason for her dismissal is unclear, but it would not have been different from the all too common injustices and discrimination suffered by her neighbors and the national African American community at the time.

Clarence Sherrill’s prejudices would soon come out into the open. On Easter Sunday, 1922, visitors arriving in Rock Creek for picnics were met with new signs marking benches “For White Only” and “For Colored Only.”31 After the NAACP organized a protest, the signs were quietly removed.

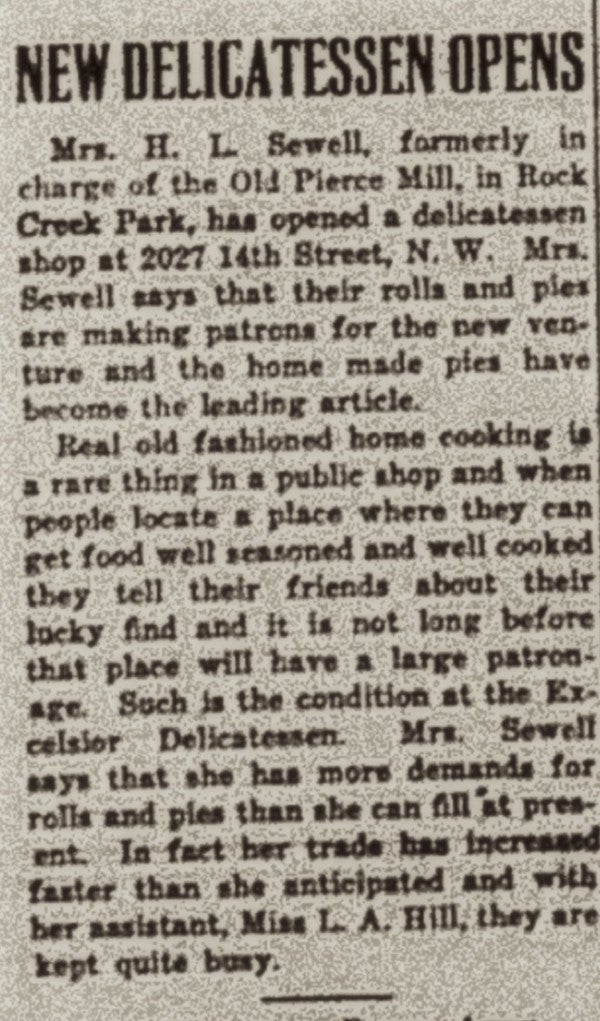

Though she had been forced out of the Teahouse, Sewell’s entrepreneurial spirit did not rest for long. Within six months, she had opened another delicatessen and café, called Balfour, at 2027 14th St. NW in the more welcoming U Street neighborhood. She was known for her “old fashioned home cooking” and continued to offer the best hospitality to her customers.32

It is unclear how long she operated this venture, but in 1922, she seemed to have been doing quite well:

“Mrs. Sewell says she has more demands for rolls and pies than she can fill at present,” The Washington Tribune reported. “Her trade has increased faster than she anticipated.”33

Special Note:

This article draws heavily on The Hattie Sewell Project, a joint research project by the Friends of Pierce Mill, Howard University Afro American Studies professor Dr. Amy Yeboah Quarkume, and her students Asan Hawkins (’21) and Yanava Ferreria (’23). The project was supported by a grant from DC Humanities in 2021.

For more on Hattie Sewell and the efforts to uncover her story, please see “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington” by Angela Kramer (Friends of Pierce Mill Executive Director); the Rock Creek Conservancy’s program “The Life and Times of Hattie Sewell”; and Hattie Sewell, a 30 minute film produced by the Friends of Peirce Mill in partnership with the National Park Service at Rock Creek Park and Howard University.

Footnotes

- 1

US National Park Service. “Peirce Mill (U.S. National Park Service).” NPS, April 10, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/places/peirce-mill.htm.

- 2

Kramer, Angela. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse.” Friends of Peirce Mill, March 7, 2023. https://www.friendsofpeircemill.org/hattie-sewell-and-the-peirce-mill-teahouse/.

- 3

Rock Creek Conservancy. The Life and Times of Hattie Sewell. 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uljNQNr2MMY.

- 4

Friends of the Peirce Mill & Howard University (Directors). (2021). Hattie Sewell (National Park Service, Ed.). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Os1dgrRzwcY

- 5

Rock Creek Conservancy. The Life and Times of Hattie Sewell. 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uljNQNr2MMY.

- 6

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 7

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 8

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 9

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 10

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 11

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 12

Friends of the Peirce Mill & Howard University (Directors). (2021). Hattie Sewell (National Park Service, Ed.). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Os1dgrRzwcY

- 13

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 14

Rock Creek Conservancy. The Life and Times of Hattie Sewell. 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uljNQNr2MMY.

- 15

Her name was Georgiana Rose Simpson; she received a doctoral degree in German philology from the University of Chicago in 1921.

- 16

Estimates have been as high as 40. See: Schaffer, Michael. “Lost Riot.” Washington City Paper, April 3, 1998. https://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/news/article/13015176/lost-riot.

- 17

Kramer, Angela. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse.” Friends of Peirce Mill, March 7, 2023. https://www.friendsofpeircemill.org/hattie-sewell-and-the-peirce-mill-teahouse/.

- 18

Kramer, Angela. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse.” Friends of Peirce Mill, March 7, 2023. https://www.friendsofpeircemill.org/hattie-sewell-and-the-peirce-mill-teahouse/.

- 19

Kramer, Angela. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse.” Friends of Peirce Mill, March 7, 2023. https://www.friendsofpeircemill.org/hattie-sewell-and-the-peirce-mill-teahouse/.

- 20

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 21

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 22

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 23

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 24

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 25

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 26

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 27

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 28

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 29

Rock Creek Conservancy. The Life and Times of Hattie Sewell. 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uljNQNr2MMY.

- 30

KRAMER, ANGELA. “Hattie Sewell and the Peirce Mill Teahouse: A Black Businesswoman in 1920s Washington.” Washington History 34, no. 2 (2022): 50–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48694020.

- 31

“Col. Sherrill and Race Prejudice.” The Washington tribune. (Washington, DC), Apr. 22 1922. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn87062236/1922-04-22/ed-1/.

- 32

“New Delicatessen Opens.” The Washington tribune. (Washington, DC), Apr. 22 1922. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn87062236/1922-04-22/ed-1/.

- 33

“New Delicatessen Opens.” The Washington tribune. (Washington, DC), Apr. 22 1922. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn87062236/1922-04-22/ed-1/.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)