Save the Suitcases! The Willard Hotel Fire of 1922

There have certainly been worse fires, but the Willard Hotel blaze of 1922 caused quite a stir. It resulted in $400,000 — about $5,400,000 today — in damages to the grand hotel and sent some of the District's most distinguished citizens and guests out into the street in their pajamas.[1] Some just moved a little more quickly than others. Apparently, emergency procedures were a little different back then.

Don’t believe us that every statesman worth his salt was staying at the Willard? In the 1860s, Nathaniel Hawthorne (who, as you might remember, had a lot to say about D.C.) commented “the Willard Hotel more justly could be called the center of Washington than either the Capitol or the White House or the State Department.”

Yeah, it was a pretty big deal. The clientele was the picture of distinction; permanent guests included Vice President Calvin Coolidge and President Warren Harding's personal physician, as well as a bevy of senators and congressmen from around the country.

The fire began in the early hours of Sunday morning, April 23, on the tenth floor in a banquet hall just vacated by the Gridiron Club. Unfortunately, nobody noticed until the flames were strong enough to be seen from the street below. The alarm was finally raised around 6 a.m. Each room in the hotel was phoned while policemen, hotel attendants, and volunteers knocked on doors telling occupants to “take their time” but to leave their room as soon as possible.[2] (Because, you know, fire waits for the rich and famous.) However, despite the obvious danger, only floors seven, eight, and nine were evacuated, and even then it was just to avoid the water that was streaming down from the firefighters’ equipment.

Yes, the elegant statesmen of the Willard were all rather cavalier about the inferno going on over their heads. More than a few were reported to have bathed and shaved before exiting, including Senator T Coleman du Pont, one of the largest stockholders of the company that owned the hotel. Coleman apparently “peacefully [took] a bath with the roof blazing above his head and the corridors running rivers.”

One’s toilette was very important, of course, and that’s why it was so scandalous that Peacock Alley, a corridor on the main level of the hotel “famous as a promenade for the great and near great,” was “crowded with scantily-clad men and women.” Many made themselves respectable in rooms off Peacock Alley, but some were brave enough to finish themselves while chatting outside with the press. In fact, a picture of two such young ladies while perched on a fire engine with hand mirrors graced the front page of the next day’s newspaper.[3]Coolidge “smoked a cigar and joked with newspapermen” while waiting for his wife to complete her toilette (Coolidge was apparently the sort who could laugh about a lot). By 8 o’clock, most of the guests from the upper floors were seated downstairs in the dining room calmly eating breakfast.

The Coolidges and the Harding's physician secured rooms at the White House, but the other some 200 guests were hard-pressed to find anywhere else to stay. The Willard had already been at capacity, and the District was stuffed to the gills with conferences and conventions that week. No worries though, everyone reportedly found a place to stay eventually. And, just so it’s clear that we know what is important, no one died or was hurt seriously in the three hours that it took to vanquish the blaze. (Apparently, those staying at the Willard knew what was important, too. After the alarm was raised, the hallways on the seventh, eighth, and ninth floors were “cluttered” with baggage as guests worked to save their wardrobes and kept the elevator busy to this end.)

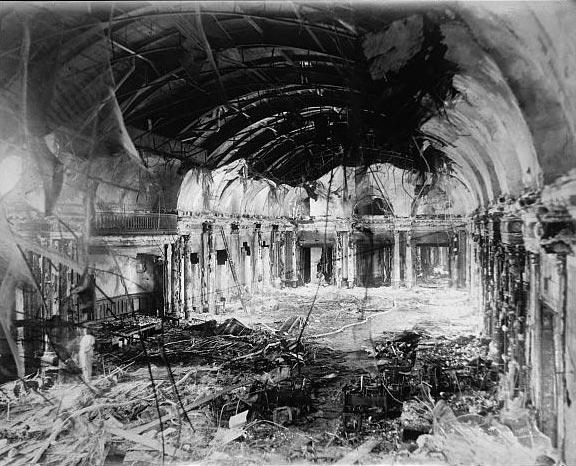

The damage from the fire was extensive. The entire tenth floor was destroyed, including two ballrooms and a banquet hall with “several pianos, scores of tables and chairs, costly rugs and other decorations.”[4] The entire floor had actually just been completely renovated the summer before at the cost of $50,000 — about $635,000 today — a special stage with “lighting effects” had been installed and the whole thing had been done in gold and mulberry.

The water hoses firemen used to fight the flames also took its toll, ruining the rugs and other decorations on the ninth floor. The spray made such an impression that one congressman “thought the weather indicated rain” and took his umbrella with him.

The Willard fire disrupted the scheduling of countless society balls (at the time of the ballroom’s destruction, it was “engaged for pretty nearly every evening”[5]) but all in all, is on the lighter side of Washington’s tragedies. The tenth floor was reopened in late September of the same year and continued to service a bundle of who’s who in Washington until it closed in 1968, reopening a second time in 1986 after more renovations.

Sources:

National Park Service register of historic places: Willard Hotel

Willard Hotel Website, History

Footnotes

- ^ The Washington Times. (Washington [D.C.]), 31 Dec. 1922. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1922-12-31/ed-1/seq-10/

- ^ The Washington Herald. (Washington, D.C.), 24 April 1922. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045433/1922-04-24/ed-1/seq-1/

- ^ The Washington Times. (Washington [D.C.]), 30 April 1922. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1922-04-30/ed-1/seq-23/

- ^ The Washington Times. (Washington [D.C.]), 24 April 1922. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1922-04-24/ed-1/seq-3/

- ^ The Washington Times. (Washington [D.C.]), 30 April 1922. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1922-04-30/ed-1/seq-23/

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)