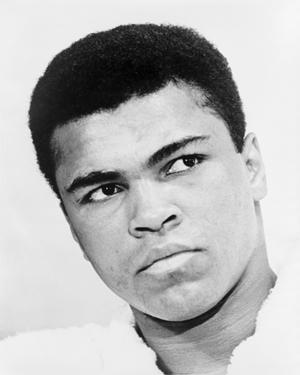

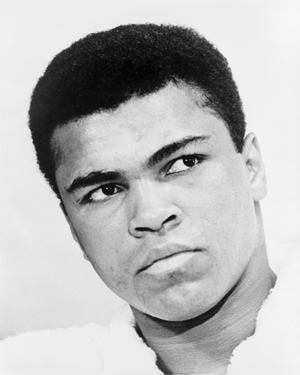

Muhammad Ali's Speech at Howard University, 1967

The PBS documentary The Trials of Muhammad Ali, covers the boxing champ's struggles outside the ring during the tumultuous mid-1960s, when his refusal to serve in the military during the Vietnam War led to him being stripped of his title, and nearly cost him his freedom. The program also explores Ali's involvement in the Black Power movement of the 1960s, and his emergence as a symbol of protest and dissent for young people of that time.

Ali's duality as a firebrand activist and a revolutionary icon is examplified, in some ways, by his controversial appearance at Howard University in April 22, 1967, where he gave a speech to African-American students just days before he refused induction in the armed forces, which led to his indictment and conviction for draft evasion.

Ali, thanks to his name-changing religious conversion and poetry-spouting braggadocio — an act which he actually developed by studying flamboyant wrestler Gorgeous George — already was a provocative figure in popular culture when the government's changing of his draft status in 1966 thrust him into the growing turmoil over the Vietnam War. In some ways, Ali's morphing into an antiwar figure was forced up on him. According to New York Times reporter Robert Lipsyste, who was with Ali the day that the boxer got the news, he was hounded by other journalists who called to badger him about his position on the war — was he a hawk or a dove? Would he be willing to kill a Vietnamese? — until he finally lost his cool. "Man, I ain't got no quarrel with them Viet Cong," he finally blurted. The offhand remark became the headline, and Ali suddenly found himself being denounced by sportswriters such as Red Smith, who likened him to "those unwashed punks who picket and demonstrate," and Murray Robinson, who demanded that "boxing should throw Clay (Ali) out on his inflated head."

But on college campuses across America, the outspoken boxer just as quickly became a hero. That was especially true at the District's Howard University, then a century-old traditionally black school that had long prided itself on producing students who could compete against the obstacles thrown up by a still-segregated American society. But as detailed in a the classic PBS documentary on the Civil Rights movement, Eyes on the Prize, a new generation of students at Howard was discontented by the status quo, and unhappy about Howard's lack of courses on black history and culture. In October 1966, they made a statement by electing as homecoming queen Robin Gregory, an activist who wore her hair in the natural Afro style that had become a symbol of black self-expression. The following April, the student Black Power Committee invited Ali to come to the campus and speak to students on the subject of African-American identity.

Four days prior to the speech, according to a Washington Post article published on April 22, 1967, the Howard campus was torn by strife, as scores of students marched in a Black Power rally and burned effigies of Selective Service director Lewis B. Hershey, Howard president James M. Nabrit, Jr., and liberal arts dean Frank Snowden. According to Ali biographer David West, University officials denied the committee an indoor venue, so Ali gave his speech on the steps of Frederick Douglass Memorial Hall, a national landmark designed by early 20th Century African-American architect Albert Cassell. According to the Washington Post's contemporary account of the event, about 800 students attended, though other sources put the crowd at more than 1,000. Ali waved a copy of a Nation of Islam newspaper, Muhammad Speaks, whose headline was "JUSTICE ON TRIAL." Except for two Howard security guards, there were no police in attendance, though six officers from the Civil Disturbance Unit stayed on call at the nearby 13th Precinct station.

The great athlete, so celebrated for his verbal flamboyance and clever turns of phrases, didn't disappoint. Ali gave what became known as his "Black is Best" speech, in which he exhorted students to abandon society's concept of them and to fashion their own, based upon pride in themselves and their people:

All you need to do is know yourself to set yourself free. We don't know who we are. We call ourselves negroes, but have you ever heard of a place called Negroland?

Ali blamed African-Americans' sense of inferiority upon a white dominated society that ignored them and their achievements, as if if they didn't exist — a message reminiscient of Ralph Ellison's 1952 novel Invisible Man, but delivered through a strident onslaught of metaphors more characteristic of Malcolm X.

See, we have been brainwashed. Everything good and of authority was made white. We look at Jesus, we see a white with blond hair and blue eyes. We look at all the angels, we see white with blond hair and blue eyes. Now, I'm sure if there's a heaven in the sky and the colored folks die and go to heaven, where are the colored angels? They must be in the kitchen preparing the milk and honey. We look at Miss America, we see white. We look at Miss World, we see white. We look at Miss Universe, we see white. Even Tarzan, the king of the jungle in black Africa, he's white!

Ali added:

The white tries to show the white as all-good. All the good cowboys ride wide horses. Angel food cake is white and devil's food cake is chocolate.

That conspiracy, he railed, concealed the truth — again, delivered in hyperbolic, almost comic metaphor:

Black dirt is the best dirt. Brown sugar causes fewer cavities, and the blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice.

For the most part, the Howard students — some clad in traditional African garb that the Post called "togas and shawls," and brandishing copies of Algerian writer Frantz Fanon's call to arms The Wretched of the Earth — seemed to eat it up. As the Post noted, Ali's contingent of bodyguards had difficulty restraining the surging audience from enveloping Ali. Shouts of "Tell it like it is!" and "Hear the word" erupted from his listeners. The boxer exorted them to "seek out" the teachings of Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad. Ali told them that he had 28 invitations from leaders of Muslim countries across the globe.

I am the brother of more than 600 million followers of Allah. You are living in the last days of hell in this country.

At the end of his speech, in what the Post called an "off-key voice," Ali launched into a rendition of a song called "A White Man's Heaven is a Black Man's Hell," originally recorded by Louis Farrakhan in 1955. The lyrics indicted whites for enslaving black Africans, stealing their natural resources and destroying their culture.

![504 Button Bright yellow protest button created by the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities (ACCD). The pin reads in black block-lettering: "Handicapped Human Rights, Sign 504, ACCD." [Source: National Museum of American History]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/504%20Button.jpeg?itok=yiaSjVx2)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)