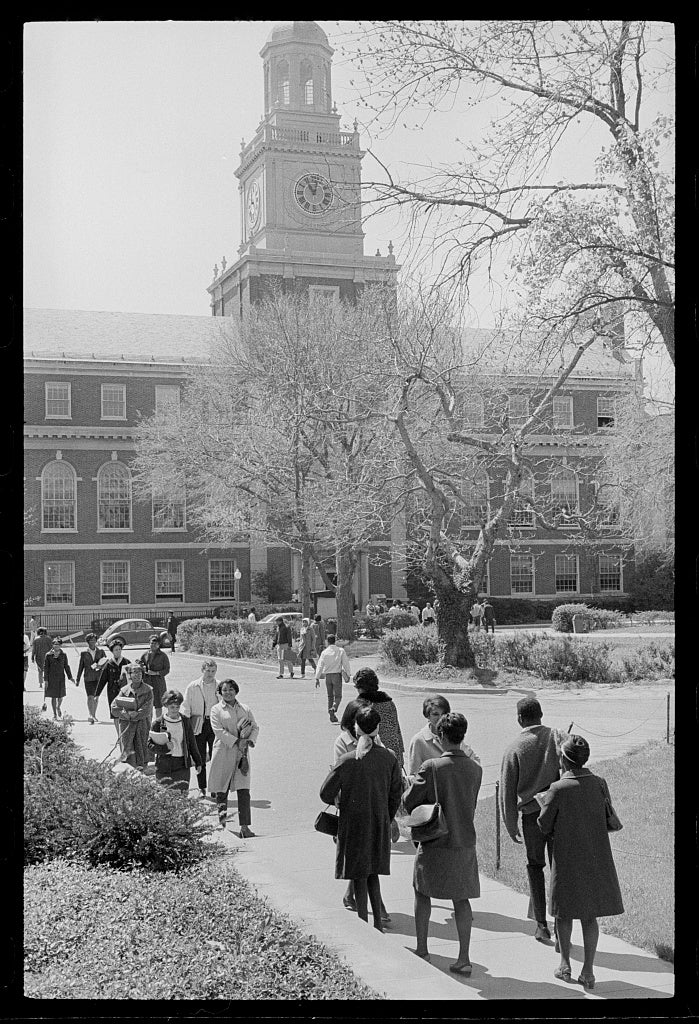

How Howard University Students Challenged its Identity as a Black University

On March 22, 1968, Adrienne Manns, senior editor of Howard University’s official student newspaper, The Hilltop, summed up the lively scene on campus in a bold editorial:

“If this is not revolution, then what is?”1

Three days earlier, one thousand students had taken over the university’s main administration building – known as the “A” building – refusing to leave. Everyday business at Howard ground to a halt.

Hilltop reporter Clyde Waite wrote: “Thus far, the ordinary demonstrator fills his days with readings primarily relative to the black revolution such as ‘The Autobiography of Malcolm X’, also with speeches, card games, and just sitting at their prescribed posts. Evening finds them huddling in what floor space they can find with blanket and pillow.”2 From the building’s entrance window, a sign in emboldened letters read “CLOSED”.

The protest was the culmination of months of tension between a portion of the student body and the administration. There were various contributing factors, but all seemed to point to a fundamental question: What was – and what should be – Howard’s identity as a Black university?

An institution chartered in 1867 to educate freedmen, Howard had long been renowned for its output of exceptional black professionals. But as the black power movement took hold in the 1960s, many students felt the administration had become “too reluctant to change” and unwilling to “adjust to the time and culture”.3 In order to be a true black university, the protestors claimed, Howard needed to transform the way it embraced and related to the larger black community.

As Manns would reflect later for the Eyes on the Prize documentary, “the black issue was that Howard should exist for the benefit of the black community” and it “ought to be involved in economic change and political change” with a purpose not only to achieve a “liberal education” and “become a member of the middle class”.4

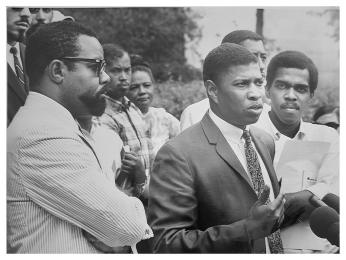

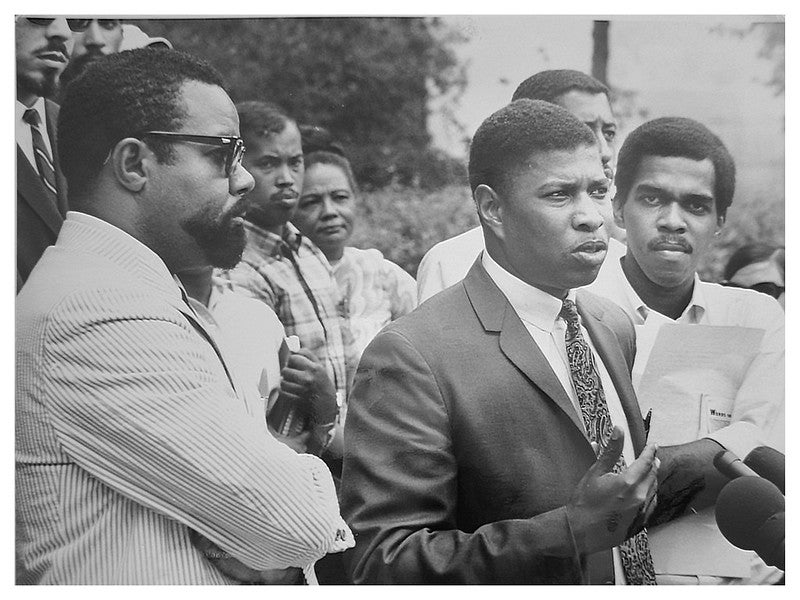

Though student led, the spirit of protest had been bolstered by some faculty members – notably Sociology professor Nathan Hare. Until his dismissal in 1967, Hare had led the University’s Black Power Committee, a group driven against what they saw as Howard’s “whitewashing” curriculum.5 It was Hare’s former students, including Manns and organizer Tony Gittens, that rallied their peers from the campus main yard to the administration building on the evening of Tuesday, March 19th.

While the A building takeover was the most extensive student protest to that point, it was, in many ways, a continuation of activism that had started months earlier. In March of 1967, the 100th anniversary of the University’s founding was clouded by tension. When Selective Service Director, General Lewis Hershey, was scheduled to speak at Howard’s Cramton Auditorium, students took their opportunity to speak out.6 Frustrated that the government could ask them to fight in a foreign country when there were significant battles to be faced at home, dozens rushed the stage under the rallying cry, “America is the black man’s true battleground.”7 On the main yard, a likeness of Hershey would be burned in effigy.8

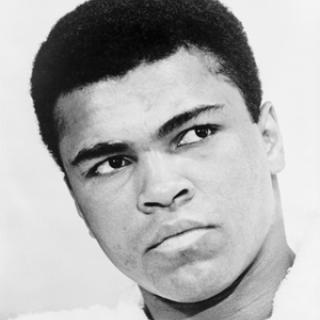

The campus was in uproar once again in late April, as Muhammad Ali made a visit to the school condemning the draft and echoing declarations of black pride.9 As he faced jail time for his refusals to fight in Vietnam, active students and faculty engaged in similar protests and soon found themselves fighting to keep their positions at the University.

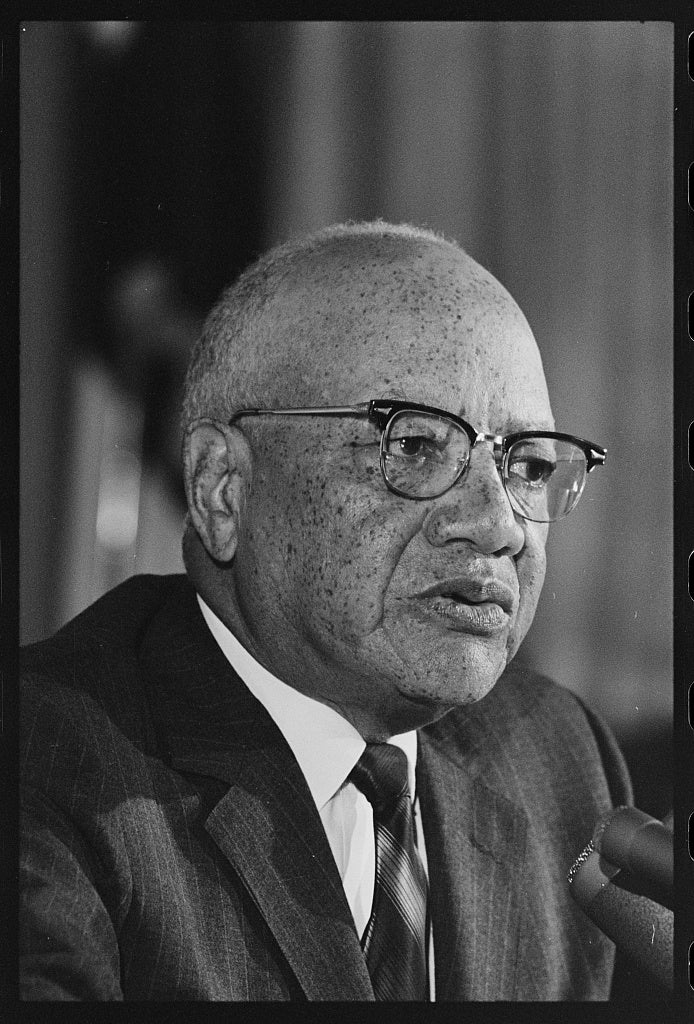

Acting to clear Howard’s good name and protect its finances, as a partially federally funded institution, University President James M. Nabrit punished those involved in the Hershey disruption by sending dismissal notices.10 Those impacted included Professor Hare and former Homecoming Queen Robin Gregrory, who, in 1966, had been the first queen to wear her natural hair.11

Sentiment towards the dismissed faculty and students – five of whom went on to successfully protest the administration decision to expel them in court12 – would touch off further protests during the 1967-68 school year.

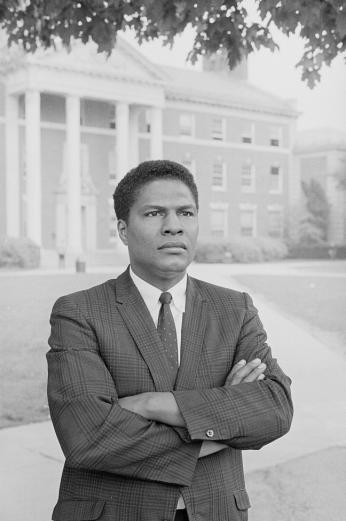

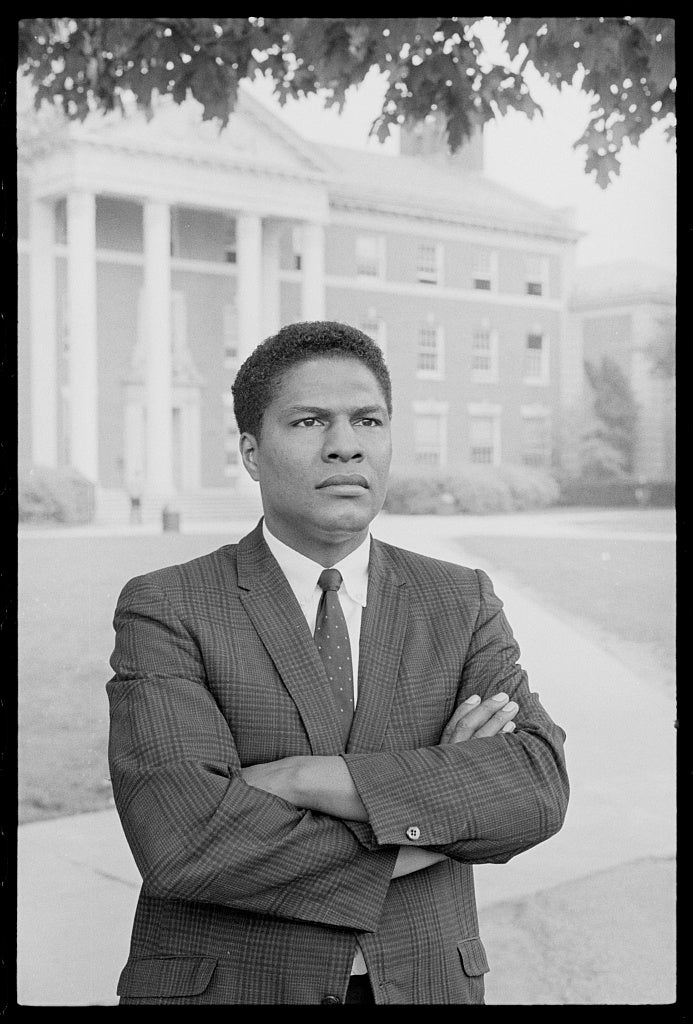

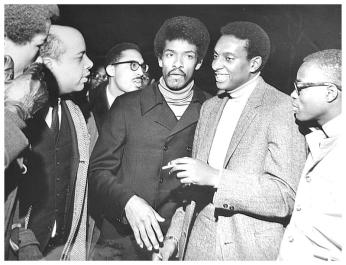

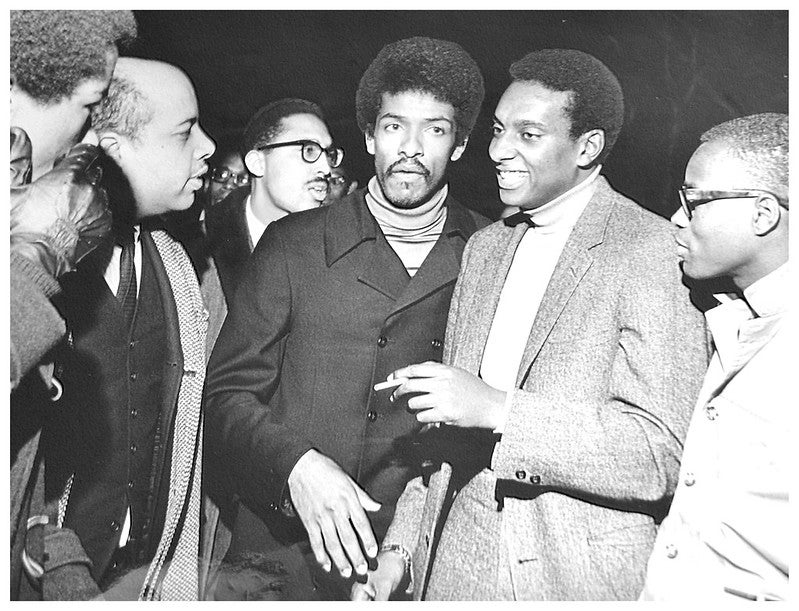

Indeed, student organizing and demonstrations became a main feature of the Hilltop throughout the fall semester of 1967. The Howard University Student Association, or HUSA, and other organizations like UJAMMA – a student coalition heavily involved with the political action on campus – brought together student leaders like Ewart Brown and Tony Gittens in hopes of compelling the school to operate as they thought a black university should.13

As Nabrit’s expulsion notices had resulted from a disciplinary hearing in which the students had no part, students demanded the creation of a student dominated judiciary.14 Additionally, activists took aim at the policy of compulsory ROTC, and the University’s enduring conservatism while embracing newer manifestations of black identity.15

In November, students staged a sit in at President Nabrit’s office to expedite administration decisions regarding the ROTC mandate for male students.16 In a “Pro Protestor” letter to The Hilltop editor, one student wrote, “the university is a training ground for the world” and the obligation to “stand up and fight for one’s beliefs” played out on Howard’s grounds when an upwards of seventy students occupied the office.17

In the wake of Howard’s 101st anniversary on March 1, 1968, feelings of dissent that had brewed in “individual student groups meeting in the dorms, between classes or private parties” were on the cusp of another explosion.18President Nabrit presided over the Charter Day event to an audience in Cramton Auditorium. Reminiscent of the previous year’s demonstrations, “a group of about 120 students filed to the front of the stage to present a list of grievances and demands which the president had not satisfactorily responded to”.19 Leaflets were distributed to the audience as they made their way down the aisles. Its text condemned the school’s vacant role in “elevating the position of Black people in this country.”20 Though an attempt was made to silence the demonstrators by cutting off the sound system, one speaker was able to assert, “black people must realize their culture and accept it before they could possibly think about other human ideas.”21

In a recent interview, Adrienne Manns recalled that she and Tony Gittens were the first to leave their seats and head towards the stage.22 She feared for retaliation from the administration, but the vision of change for the University among her peers was strong. When 39 senior leaders received letters condemning them to a judiciary hearing on Tuesday, March 19th – a decision considered a betrayal on the part of the administration – student leaders rallied hundreds to the campus “nerve center” and took over the A building.23

The unrest at Howard became nationwide news. The Los Angeles Sentinel invoked imagery of the Civil War likening the student demonstration as a “fight for freedom all over again” considering the historical struggle for black education.24 Other outlets were less supportive, however – including the Chicago Defender which called the Howard shutdown the “worst crisis in its 101-year history”.25

While not all students supported the A building takeover, the Howard community reaction was generally supportive. The activists’ efforts were seconded by some faculty, parents, and civil rights leaders – notably Stokely Carmichael, himself a Howard alum and leading advocate of black power.26

In the midst of the occupation, Manns spoke for the protestors: “We feel the administration must give some public indication that they will move to establish democracy and a black oriented curriculum before we can discontinue our protests. Our position is legitimate, and we must continue to push for all of our demands.”27

In a later interview, freshman Michael Harris explained: “I think it was a situation where they thought that Howard University should serve another purpose other than preparing people to fill slots in white society. This, I think was really the deep underlying cause for the unrest and took specific overtones on campus.”28

Many members of the Board did not fully embrace student enthusiasm to completely transform the identity of the University. To prioritize black history classes, and improve upon student power was one matter; uprooting the long-held reputation of Howard was another. The rhetoric of black power and pride that became inherent in the student’s actions - as a result of their relationship with mentors like Nathan Hare and involvement in “militant” organizations - was regarded as a threat to the character of the University.29 To the protestors, Nabrit and the administration represented an “outdated and outmoded” identity of the school under which autocracy, curfews, and exceptionalism prevailed.30

The tense scene on Sixth Street NW during March of 1968 came just weeks after a civil rights protest at South Carolina State University in Orangeburg, SC had ended in three fatalities when city police fired upon the crowd of student protestors.31 The Orangeburg Massacre had moved many on Howard’s campus. To avoid a similar outcome at Howard, a mutual line of communication needed to be established quickly between students and administration officials.

Still negotiations got off to a rocky start. President Nabrit who had been absent since the beginning of the takeover, initially refused to meet with student leaders and threatened to get the federal government involved.32 However, within a few days the student steering committee and members of the administration were negotiating.

During an exhaustive overnight session on March 22, they reached a series of compromises. On Saturday, March 23, their five-day occupancy ended when Board members vowed to protect participants from disciplinary charges, make further room for student voices, and “make an effort to see that Howard becomes more attuned to the times and the mood of its people.”33

The spirit of activism that empowered students that eventful semester was replicated at Black universities across the country. During the week of the takeover, The Hilltop reported that “Morgan State, Cheyney, and Fisk had been closed due to demonstrations similar to Howard’s” which prompted “a rousing ovation and cheers” in the A Building.34

While student leaders considered their A building takeover “a step” towards making Howard the black university they envisioned, they promised to continue pushing for change in the weeks and months that followed, and chip away at the mold of conservatism that they felt chained Howard University to the past.35

In a letter to the editor in the following weeks edition, published March 29, an anonymous former student wrote: “Howard has undergone a permanent change. The students are now the determiners of its direction. This is true not simply because they present force that can only be met with acquiescence, but their organizing ability and seriousness of purpose have proven them worthy of this power.”36

One of those permanent changes was the formation of the Afro American Studies department, which began during the 1968-1969 academic year. It’s first chairman, Professor Russel Adams recalled student emphasis that there ought to be a program whose responsibility was to “look at the experiences of persons of color, especially in the Western Hemisphere.”37The result has been a comprehensive curriculum that specifically “looks back…looks around…and looks to the future” of the black experience in America.

For more photos from the protests at Howard from the late 60s, check out the Washington Area Spark Collection.

Footnotes

- 1

Adrienne Manns, “The Motley Crowd,” The Hilltop, March 22, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_196070/168/.

- 2

Clyde Waite, “Students Take Over The University’s Administration Building,” The Hilltop, March 22, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_196070/168/.

- 3

Cindee Marshall, “Sit-Iners Surveyed,” The Hilltop, March 29, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1168&context=hilltop_196070.

- 4

“Ain’t Gonna Shuffle No More: 1964-1972,” Eyes on the Prize, 1990, https://www.kanopy.com/en/dclibrary/watch/video/285132/285124.

- 5

“Black Power Committee Holds Press Conference,” The Hilltop, April 7, 1967, https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1138&context=hilltop_196070.

- 6

“Hershey Retreats Under Attack; Apologies and Invitation Extended,” The Hilltop, April 7, 1967, https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1138&context=hilltop_196070.

- 7

“Hershey Retreats Under Attack; Apologies and Invitation Extended,” The Hilltop, April 7, 1967, https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1138&context=hilltop_196070.

- 8

WETA PBS, How Muhammad Ali’s Speech at Howard University Helped Inspire a Student Uprising, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E3Cf9T5z3X4.

- 9

WETA PBS, How Muhammad Ali’s Speech at Howard University Helped Inspire a Student Uprising, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E3Cf9T5z3X4.

- 10

“Howard Dismisses Teachers, Students,” New York Amsterdam News (1962-), July 8, 1967, https://www.proquest.com/docview/226645796/abstract/AFE2BF5EB0334165PQ/4.

- 11

Jerrod Wimbish, “Student Activism and the Historically Black University: Hampton Institute and Howard University, 1960–1972” (Harvard University, 2000), https://www.proquest.com/docview/304591217/BA0581504AD949C9PQ/7?accountid=11490&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses.

- 12

WETA PBS, How Muhammad Ali’s Speech at Howard University Helped Inspire a Student Uprising, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E3Cf9T5z3X4.

- 13

Brenda Adams, “Students Struggle For Black University,” The Hilltop, March 29, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1168&context=hilltop_196070.

- 14

Jerrod Wimbish, “Student Activism and the Historically Black University: Hampton Institute and Howard University, 1960–1972” (Harvard University, 2000), https://www.proquest.com/docview/304591217/BA0581504AD949C9PQ/7?accountid=11490&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses.

- 15

Jerrod Wimbish, “Student Activism and the Historically Black University: Hampton Institute and Howard University, 1960–1972” (Harvard University, 2000), https://www.proquest.com/docview/304591217/BA0581504AD949C9PQ/7?accountid=11490&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses.

- 16

Hugh Warner, “Nabrit’s Deadline Near For Decision On ROTC,” The Hilltop, November 17, 1967, https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1155&context=hilltop_196070.

- 17

“Pro Protestors,” The Hilltop, November 17, 1967, https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1155&context=hilltop_196070.

- 18

Adrienne Manns, “The Motley Crowd,” The Hilltop, March 22, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_196070/168/.

- 19

Clyde Waite, “Students Disrupt Charter Day, Claim Nabrit Broke Promise,” The Hilltop, March 8, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1165&context=hilltop_196070.

- 20

Clyde Waite, “Students Disrupt Charter Day, Claim Nabrit Broke Promise,” The Hilltop, March 8, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1165&context=hilltop_196070.

- 21

Clyde Waite, “Students Disrupt Charter Day, Claim Nabrit Broke Promise,” The Hilltop, March 8, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1165&context=hilltop_196070.

- 22

Kaylene Dial Armstrong, “Telling Their Own Story: How Student Newspapers Reported Campus Unrest, 1962-1970” (Ph.D., United States -- Mississippi, The University of Southern Mississippi, 2013), https://www.proquest.com/docview/1461742774/abstract/74F465A3331145F2PQ/1.

- 23

Adrienne Manns, “The Motley Crowd,” The Hilltop, March 22, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_196070/168/.

- 24

Chuck Porter, “Howard U’s Student Power Struggle: Students Paralyze Historic School in Wash., D.C.,” Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-), March 28, 1968, https://www.proquest.com/docview/564876902/abstract/692F9EE3C1244473PQ/1.

- 25

Ethel Payne, “Howard University Students Take Over Key Campus Building,” Chicago Daily Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1966-1973), March 23, 1968, https://www.proquest.com/docview/493433291/abstract/E0754358D98C4EC1PQ/3.

- 26

“Students Take Over The University’s Administration Building,” The Hilltop, March 22, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_196070/168/.

- 27

“Ain’t Gonna Shuffle No More: 1964-1972,” Eyes on the Prize, 1990, https://www.kanopy.com/en/dclibrary/watch/video/285132/285124.

- 28

Jerrod Wimbish, “Student Activism and the Historically Black University: Hampton Institute and Howard University, 1960–1972” (Harvard University, 2000), https://www.proquest.com/docview/304591217/BA0581504AD949C9PQ/7?accountid=11490&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses.

- 29

“Ain’t Gonna Shuffle No More: 1964-1972,” Eyes on the Prize, 1990, https://www.kanopy.com/en/dclibrary/watch/video/285132/285124.

- 30

Cindee Marshall, “Sit-Iners Surveyed,” The Hilltop, March 29, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1168&context=hilltop_196070.

- 31

Smithsonian Magazine and Lorraine Boissoneault, “In 1968, Three Students Were Killed by Police. Today, Few Remember the Orangeburg Massacre,” Smithsonian Magazine, accessed November 20, 2024, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/1968-three-students-were-killed-police-today-few-remember-orangeburg-massacre-180968092/.

- 32

Clyde Waite, “Administration To Get Injunction,” The Hilltop, March 22, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_196070/168/.

- 33

Cindee Marshall, “Sit-In Proves To Be Effective,” The Hilltop, March 29, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1168&context=hilltop_196070.

- 34

Cindee Marshall, “Sit-In Proves To Be Effective,” The Hilltop, March 29, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1168&context=hilltop_196070.

- 35

“Ain’t Gonna Shuffle No More: 1964-1972,” Eyes on the Prize, 1990, https://www.kanopy.com/en/dclibrary/watch/video/285132/285124.

- 36

“Students Organized,” The Hilltop, March 29, 1968, https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1168&context=hilltop_196070.

- 37

Larry Crowe, Russell Adams details the history of Afro-American studies at Howard University, pt. 2, July 28, 2003, https://da-thehistorymakers-org.proxyhu.wrlc.org/story/192725;q=howard%20university%201968.

![504 Button Bright yellow protest button created by the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities (ACCD). The pin reads in black block-lettering: "Handicapped Human Rights, Sign 504, ACCD." [Source: National Museum of American History]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/504%20Button.jpeg?itok=yiaSjVx2)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)