The Night 'West Side Story' Opened in Washington

When West Side Story premiered in the summer of 1957, Felicia Montealegre wanted to be in Washington.

Felicia, wife of composer Leonard Bernstein, had come down with the flu while on a trip to Chile and was missing the August 19 premiere of Bernstein’s show at The National Theatre. A contemporary retelling of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet that takes place in New York’s Upper West Side, the show was scheduled to open in Washington for a three-week pre-Broadway tryout.

"Well, look-a me. Back to the nation’s capitol, & right on the verge,” Bernstein wrote to Felicia days before the premiere. “This is Thurs. We open Mon. Everyone’s coming, my dear, even Nixon and 35 admirals. Senators abounding, & big Washington-hostessy type party afterwards.”

After hearing news of the premiere’s success, Felicia sent her husband a letter from Chile.

“I’m bursting with pride and frustration — of all the moments to miss sharing!” she wrote. “Oh God how exciting it must have been! Were you very nervous — did you sit through it or pace?”

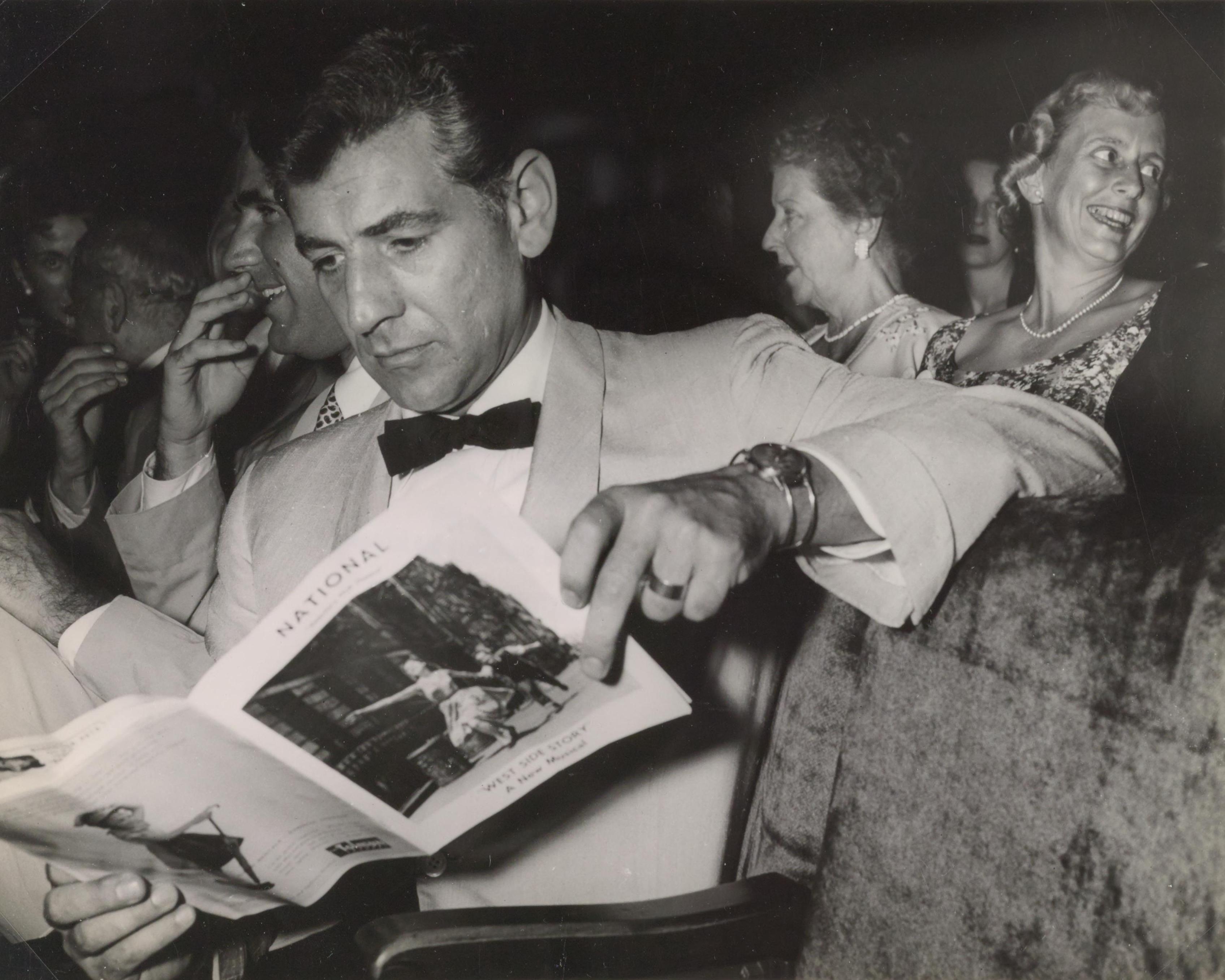

Bernstein wasn’t nervous, and he didn’t pace. It was opening night, and Bernstein stood in the theater among senators, ambassadors, Mrs. Robert Kennedy, and Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter when an acquaintance grabbed his arm and felt his pulse. It felt normal. Bernstein was calmer than she was, the woman announced.

According to National Theatre staffers, the audience was the dressiest they had seen in a long time. But perhaps less renowned than the prominent political leaders in the theater, that night was a woman named Helen Coates, whom Bernstein described as “someone I couldn’t live without.” Coates had been Bernstein’s music teacher when he was 14 and had worked as his secretary since. Also in attendance was associate producer Roger L. Stevens, who bought his own ticket. He sat in the last row, in the center aisle. A superstitious man, he refused to sit anywhere else.

Throughout the evening, Bernstein remained a dynamic presence in the theater — he joked with friends, hugged and kissed audience members, and spoke to reporters and admirers. At one point, a woman approached Bernstein and said that she used to be a social worker in a rough neighborhood with a lot of gang activity, just like the setting of West Side Story.

“It’s all so real, so true,” she told him. “It chills my blood to remember.”

“It isn’t meant to be realistic,” Bernstein said. “Poetry — poetry set to music — that’s what we were trying to do.”

In the weeks leading up to the premiere, Bernstein talked a lot about poetry. He wrote to Felicia near the end of July complaining that the “‘big,’ poetic parts” of his score — which were also the parts that he liked the most — were being criticized for being too operatic, and a show that was too operatic wouldn’t be as profitable. “Commercial success means so much to them,” he wrote. “To me too, I suppose — but I still insist it can be achieved with pride. I shall keep fighting.”

“You are so far ahead of all that mediocrity,” Felicia wrote back, “and in the long run they’re only interested in the ‘hit’ aspect of the theatre. What you wrote was important and beautiful. I can’t bear it if they chuck it out — that is what gave the show its stature, its personality, its poetry for heaven’s sake!”

One of the critics of Bernstein’s big, poetic score was Stephen Sondheim, the show’s 27-year-old lyricist. Sondheim also talked a lot about poetry. But for him, poetry meant simplicity.

"My idea of poetic lyrics is, because music is so rich, I think you have to underwrite them, not overwrite them," he told NPR in 2007. "And that accounts for lines like, 'Maria / I just met a girl named Maria,' because with music that soars that way, if you start trying to put 'poetry' — or purple prose — into it, it just becomes like an overly rich fruitcake."

Sondheim was a late addition to the show’s creative team. Before Sondheim — and even before Bernstein — it was Jerome Robbins who originally thought to turn Romeo and Juliet into a modern love story.

“I remember all my collaborations with Jerry in terms of one tactile bodily feeling: composing with his hands on my shoulders,” Bernstein said. “I can feel him standing behind me saying, ‘Four more beats there,’ or ‘No, that’s too many,’ or ‘Yeah — that’s it!’”

Robbins, who was also the show’s director and choreographer, came to Bernstein in 1949 with the idea to create a show about the Jews and the Catholics at the overlap of Easter and Passover. The collaborators eventually abandoned the religious conflict (the Jews and Catholics became Sharks and Jets, rival gangs on the West Side). Later that year, Bernstein and Robbins asked Arthur Laurents to write the book, and Laurents asked Sondheim to write the lyrics.

The collaborators revised and rewrote through the summer up until the premiere, and Bernstein was getting frustrated (“I never sleep: everything gets rewritten every day,” Bernstein complained to Felicia). Scenes were switched around, the opening number was changed, and entirely new songs were added.

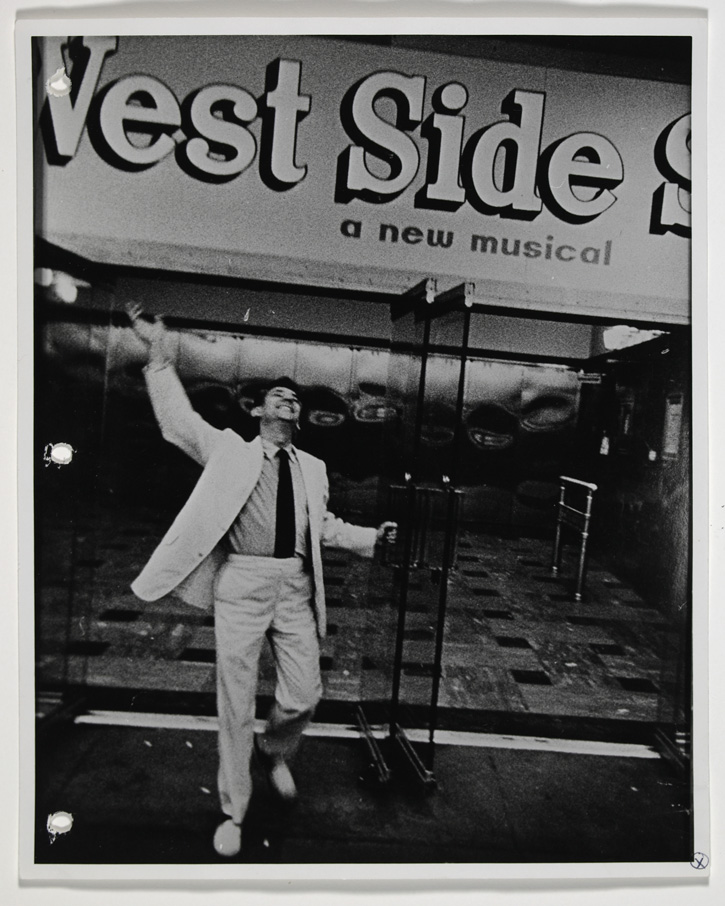

But when the surprisingly calm composer of big, poetic scores attended the premiere and saw the first performance of the finished show, he was satisfied.

“All the peering and agony and postponements and re-re-re-writing turn out to have been worth it,” he wrote in his log on August 20. “There's a work there; and whether it finally succeeds or not in Broadway terms, I am now convinced that what we dreamed all these years is possible; because there stands that tragic story, with a theme as profound as love versus hate, with all the theatrical risks of death and racial issues and young performers and ‘serious’ music and complicated balletics.”

Reviews of the show were largely positive. And soon, it sold out for the entire five-week run. Bernstein had lunch at the White House, and he said everyone there was talking about West Side Story.

“It’s only Washington, not New York; don’t count chickens,” Bernstein wrote to Felicia. “But it sure looks like a smash.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)