How Helen Hayes Helped Desegregate the National Theatre

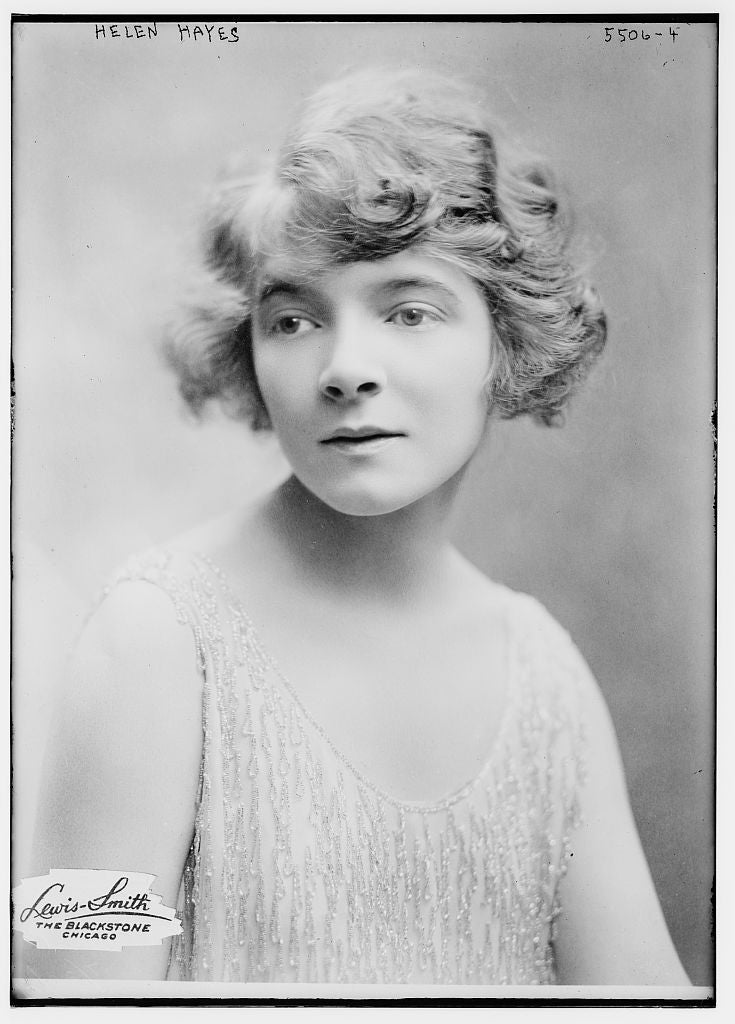

There are two things that all D.C. residents love: the first lady and the performing arts. It’s no surprise then that in the capital, “First Lady of American Theatre” Helen Hayes is an icon. Born in 1900 in Washington D.C., Hayes’ career spanned nearly eighty years. She was the first EGOT (Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony) recipient to be awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom from Ronald Reagan in 1986.

But out of all her accomplishments, perhaps one of the most overlooked is Helen Hayes’s involvement in the desegregation of the National Theatre.

The daughter of an aspiring actress, Hayes made her stage debut at age five at the Belasco Theater at Lafayette Square, across from the White House.[1] After her Broadway performance and nationwide tour in Pollyanna, Hayes debuted at the National in 1919 in On The Hiring Line. She played at the National frequently, including the debut of one of her most famous roles: Queen Victoria in Victoria Regina in 1935. When the production moved to Broadway, Queen Victoria’s granddaughter, Queen Victoria of Spain, was reportedly astonished at Hayes’s regal performance of her grandmother and invited her to tea.[2]

However, Hayes’ performances could only be witnessed by a fraction of Washington D.C.’s population. Thanks to Jim Crow legislation, black people were banned from attending District theatres in 1910. While the policy led to a proliferation of theaters and clubs on U Street, also known as “Black Broadway,” audience members and performers felt the impact of discrimination.

The policy led to Marian Anderson’s famous performance at the Lincoln Memorial after she was denied the opportunity to perform at Constitution Hall. Similarly, famed singer and actor Paul Robeson gave an open-air concert on the banks of the Potomac in 1943 but skipped Washington D.C. and Baltimore in the national tour production of Othello that same year due to the discriminatory theater policies of the cities.[3]

The segregation policy had been lifted only a handful of times in the National’s history for premier black performers. The musicals At Home Abroad and As Thousands Cheer both starred Ethel Waters. Porgy and Bess also came to the National in 1936 for a one-week engagement. In 1942, a War Department production called This is the Army attended by President Roosevelt had a desegregated audience.

Yet in 1947, when President Truman and his family went to the National for a production of Blossom Time, the tone in Washington had changed. The National Theatre was in the midst of a lawsuit from Edward S. Henderson, who accused the theatre of racial discrimination for refusing to sell him a ticket to the December 1946 show Eagle Rampant.[4] The theatre was picketed by members of the Committee for Racial Democracy, a local civil rights organization closely associated with the D.C. branch of the NAACP.[5] President Truman, seen as complicit to the racism in the nation’s capital, avoided eye contact with the protestors.

The Committee for Racial Democracy and NAACP picketed for months but made little progress until in April 1947, when the Actors’ Equity Association joined the fight. Actors such as Ingrid Bergman had been “disgusted” by the segregation they witnessed while performing in Washington D.C., Actors’ Equity declared they would forbid their members to play at the National Theatre unless it was integrated by June 1, 1948.[6]

The National Theatre didn’t budge. Owner Marcus Heiman refused to change the policy, citing “long established custom and deep-seated feeling” and potential loss of revenue. In a letter to the editor of The New York Times, Actors’ Equity Association President Clarence Derwent pointed out that the segregation policy had been in place for less than thirty years. Even if that was the case, he said, such persons would “swallow their prejudices and come rushing to the box office” to see Alfred Lunt, Lynn Fontanne, or Helen Hayes.

Derwent encouraged Heiman to open his doors in “a Lincolnian gesture” and be on the right side of history.[7] Actors’ Equity moved the boycott date back to August 1, 1948, in hopes that the judge in the Henderson case would force the National Theatre to integrate.

In the meantime, Hayes took advantage of her fame to demonstrate that Washington was ready for desegregated theatres. Fresh off her win of the first Tony Award for Best Actress in a play for Happy Birthday, Hayes also happened to be Vice President of Actor’s Equity.[8]

In June 1948, Hayes played an eight-day engagement of J.M. Barrie’s play Alice-Sit-by-the-Fire at the integrated Olney Theatre in Montgomery County, Maryland. Much to Clarence Derwent’s prediction, the show sold out two weeks before opening night.[9]

At the end of the show’s run, Hayes wrote an eloquent letter to the editor of The Washington Post about her experience. Hayes praised the integrated audience of over 9,100 and said that the successful run was “an overwhelming and gratifying indication” that D.C. residents were ready for integrated theatres. For Hayes, integrated theater was “actively and conscientiously” practiced democracy, the epitome of what the District should stand for.[10]

Unfortunately, the judge on the National Theatre lawsuit did not agree. He dismissed the case of racial discrimination two days before Hayes’ letter was published. However, National had felt the pressure — and the loss of revenue from boycotts — and decided to convert into a movie house in August rather than give into Actors’ Equity’s demands.[11]

Now D.C. was faced with a new problem altogether: it lacked a legitimate theater. The blacked-out stage was a national political embarrassment. How could Washington D.C. be a world capital without a theatre? How could the United States be a democratic leader to the world when its own theatres practiced segregation? D.C.’s political vulnerability made it the perfect place for the NAACP and Equity to stage a protest.[12]

Actors’ Equity’s solution was to reopen the Belasco Theater, where Hayes had made her stage debut, which had since been transformed into a Treasury Department warehouse.[13] Despite the promise of federal support from 50 senators, a reopened Belasco stage never materialized.[14]

Washington D.C. remained without a theatre until 1950, when opportunity finally appeared in an unlikely place: the Gayety, a burlesque theatre on 9th St. NW. The Gayety, famous for its long-legged dancers and well-known audience, such as Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, had been in decline for years. It reopened as a legitimate theater in March 1950 and was followed by the Arena Stage in August.[15] Both theatres were successful and served packed houses of integrated audiences.[16]

In May 1952, the National Theatre had a change in the lease and with it, a change of heart. The new owners, Richard Aldrich and Richard Meyers, announced that “it was a privilege and an honor” to return the National into a proper stage, while “striking a blow” at the evil of segregation.[17]

The first show to play at the newly-integrated National, Call Me Madam, included a nineteen-year-old D.C. native in the company: Chita Rivera. Five years later, the National hosted the world premiere of West Side Story.

As for Hayes, she was welcomed back to the National’s stage in 1953 as the lead in Mrs. McThing. Washington Post drama editor Richard L. Coe applauded Hayes’s absence as much as her acting:

Miss Hayes took an early stand and did not play here during the dispute but pointedly did act at the non-discriminating, nonsegregating [sic] Olney. More Southern than Northern, Miss Hayes was on record early and never wavered. So, tomorrow night, a second cheer is in order for this aspect of her outspoken courage.[18]

Hayes was pleased to be back on stage in Washington. While she “hurt many of [her] old friends” with her stance, she reaffirmed that “any form of segregation is outrageous and revolting, particularly in our Nation’s capital, the showcase of democracy.”[19]

Even after her retirement from the stage in 1971, Helen Hayes continued to advocate for the arts. In 1983, the Helen Hayes Awards were established to foster excellence in the Washington D.C. regional theatre. Today, the Helen Hayes Gallery at the National Theatre hosts free programs for children. The National Theatre may not have been the wonderful performing arts center it is today without its First Lady.

Footnotes

- ^ Evely, Douglas E., Dickson, Paul, and Ackerman, S.J."The White House Neighborhood" On This Spot: Pinpointing the Past in Washington D.C. (Capital Books: 2008) 166.

- ^ "Biography," The Official Web Site of Helen Hayes, Accessed June 14, 2016.

- ^ Ray C.B. Brown, "Watergate Crowd Hears Robeson Sing," The Washington Post, June 26, 1943. Billy Bows, "Paul Robeson Will Leave Out D. C. and Baltimore during 'Othello' Tour," The Pittsburgh Courier, June 19, 1943, City Edition.

- ^ "D.C. Jim Crow Deflated: Helen Hayes Plays to Mixed Audience in Md.," Afro-American, June 12, 1948.

- ^ "Trumans Ignore Picket Line at Jim Crow Theatre," Los Angeles Sentinel, January 30, 1947.

- ^ "AEA Timeline | 1940's." Accessed June 13, 2016. http://www.actorsequity.org/AboutEquity/timeline/timeline_1940.html.

- ^ Clarence Derwent, "Equity's Head Appeals to Marcus Heiman for End of Negro Ban in Washington," New York Times, April 06, 1947.

- ^ Hayes shared the first Tony Award for Best Actress with Ingrid Bergman.

- ^ "D.C. Jim Crow Deflated.”

- ^ Helen Hayes, "Nonsegregated Theater," The Washington Post, June 11, 1948.

- ^ "D.C. Jim Crow Deflated.”

- ^ Richard L. Coe, “Control of Bookings is Heiman's Ace,” The Washington Post, November 28, 1948.

- ^ Krefft, "Belasco Theatre."

- ^ "Belasco Revival," The Washington Post, September 18, 1949.

- ^ John DeFerrari, "Lost Washington: The Gayety Theater," Greater Greater Washington, January 26, 2011, Accessed June 14, 2016. http://greatergreaterwashington.org/post/8960/lost-washington-the-gayet…

- ^ Richard L. Coe, "First Gayety Season Proves Ours is a Hot Theater Burg," The Washington Post, June 03, 1951.

- ^ "National Theatre to go Interracial," Afro-American, November 17, 1951.

- ^ Richard L. Coe, "Helen Hayes is Indeed the Right Party," The Washington Post, March 01, 1953.

- ^ "Theater Wing here Honors Helen Hayes," The Washington Post, March 13, 1953.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)