The Perils of Pandemic and War: Spanish Flu Brings D.C. to its Knees

It was the start of October and the dog days of summer in the nation’s capital had officially come to an end. The crisp autumn air, a relief to most Washingtonians in years past, was an ominous foreshadowing of the days and weeks to come. There would be no more open windows in homes, streetcars, or workplaces for the foreseeable future. While keeping as much heat as possible inside a building is self-explanatory, warmth was not the only invisible entity kept within enclosed places that fateful fall of 1918.

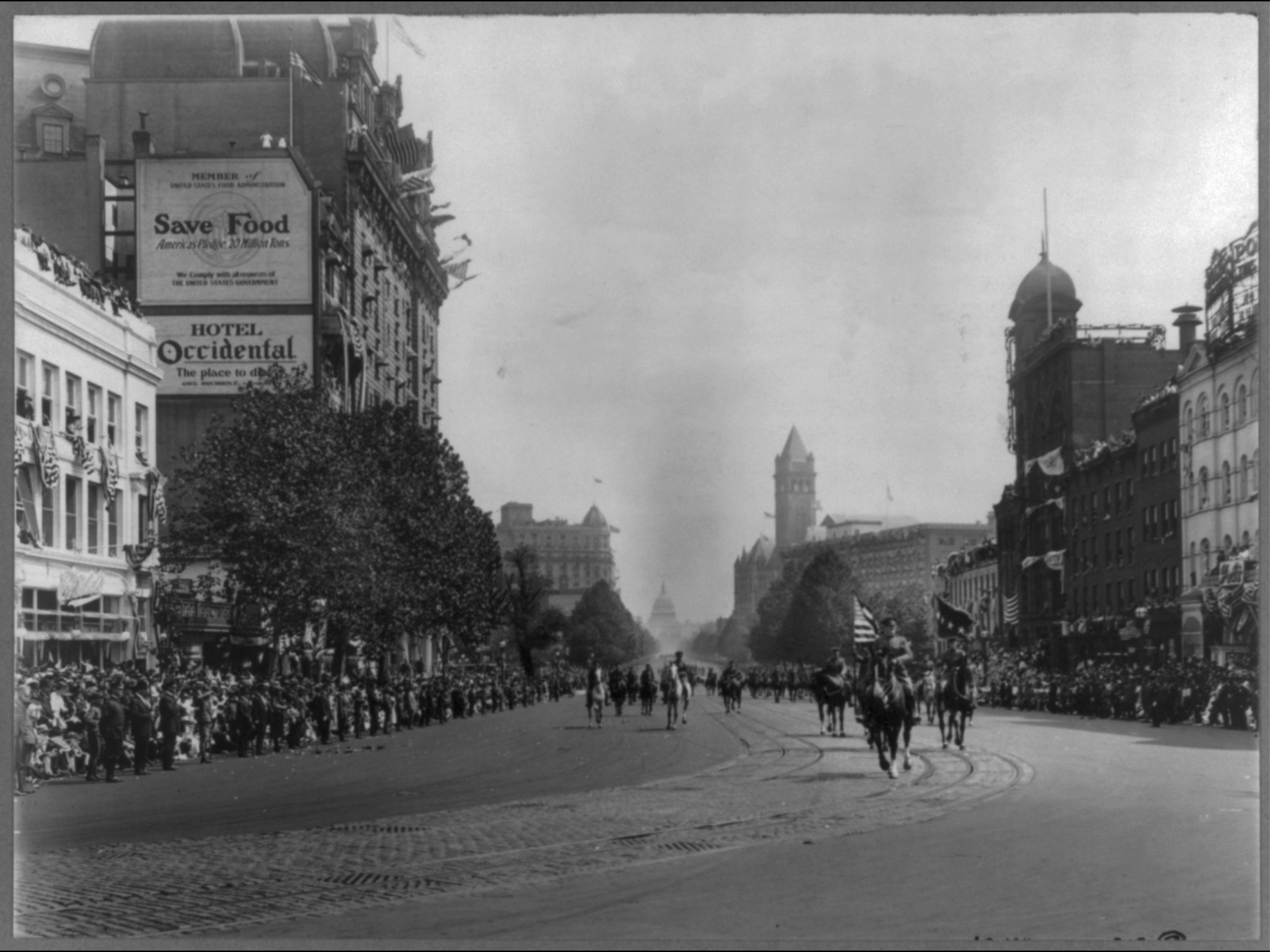

The nation’s attention, of course, was preoccupied with what was happening on the battlefields of Europe. For over a year, the United States had fought beside the beleaguered forces of the Allies in the Great War.[1] From the American entrance into the conflict in April 1917 until September 1918, the population in Washington, DC swelled.[2] Much like it would during World War II, the District became the hub for all aspects of the planning and execution of war activities.[3] The federal government grew exponentially to support the war effort and, as scores of men — including many government workers — were drafted into the military.[4] Thousands of them found themselves stationed in the various military installations in and around the city.[5]

The influx of service men and war workers to the District caused the city’s population to skyrocket. Before the war, Washingtonians numbered around 350,000.[6] By war’s end in November 1918, this number ballooned to 526,000 – a 66% increase. [7]

Washington reeled from the staggering numbers of people pouring into the city to aid in the war effort.[8] Housing quickly became scarce and overcrowded.[9] The cost of food and general living expenses inflated much too fast for wages to keep up.[10] Despite the poor living conditions in the nation’s capital, women from across America saw it their patriotic duty to sacrifice their lives at home and come to Washington to aid in America’s first total war. No good deed goes unpunished, though.

Trouble was brewing for months in the United States. In March of 1918, word began traveling of a flu-like illness slowly spreading throughout the country from its place of origin, Camp Funston, Kansas.[11] The sickness swept through the ranks of the American military, knocking many-a-men down for a few days, but killing very few.[12] This influenza epidemic caused few in DC much concern during that spring. The Evening Star, for example, spent little time discussing the rapid increase of service members hospitalized by the illness.[13]

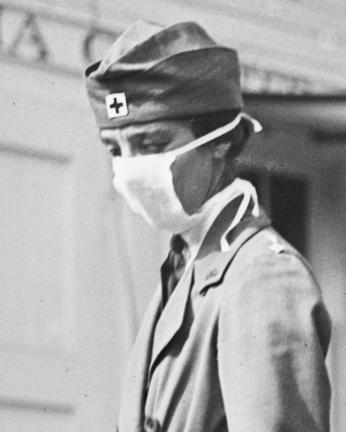

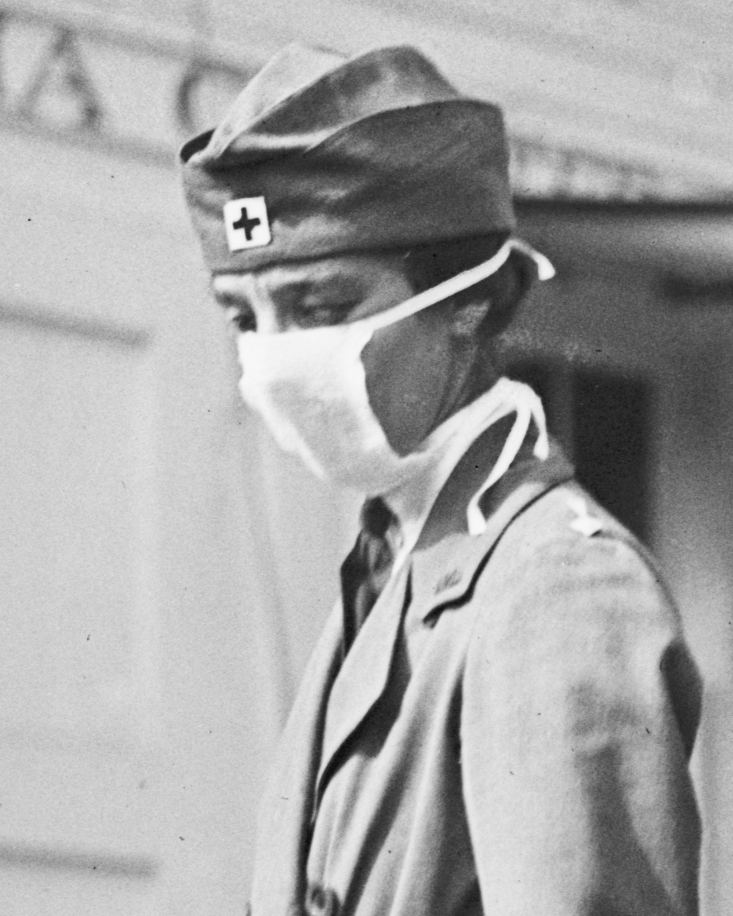

As spring melted into summer, however, an increasing number of Americans began taking note of the scourge. The epidemic found its way over to the trenches in Europe where it wreaked havoc on both sides of the conflict.[14] Back in the U.S., cases of the Spanish Flu (as it was inaccurately named – it did not originate in Spain) increased again during August and September. As the plague claimed more and more victims across the country, D.C. newspapers relayed reports. However, there seemed to be relatively little attention paid to how to protect the District from the seemingly inevitable spread of the malady to DC.[15] And spread it did.

On September 20, Dr. William C. Fowler, District Health Officer, confirmed the first cases of Spanish Flu within the confines of the city.[16] Just one day later, Washington faced the stark reality that the disease was not only in the city, but it had begun killing.[17] John W. Clove of 1103 Florida Avenue was the first person to die in the District.[18] Despite the death and the rising number of confirmed cases in DC, city officials dragged their feet on taking accepted public health measures of the day such as enacting quarantines, claiming that they were not necessary given the situation.[19] An Evening Star headline on September 24 reassured readers, “Influenza Fails to Gain in DC: No New Cases Reported Today to the Health Officer.”[20] Underestimating the situation would prove to be D.C.’s fatal flaw – many times over.

If only those same health authorities had heeded the lessons being played out in Boston, the first major American city to be affected.[21] The second and far more deadly strains of the flu first appeared in America at Camp Devens, outside of Boston, in late August and early September.[22] Before health officials knew what was going on, the illness spread into the civilian population in Boston, spurred on by mass gatherings surrounding the war effort.[23] Quickly, the number of daily infections reached the thousands and daily deaths rose to over a hundred.[24]

But during the final week of September, Washingtonians and Congress alike were preoccupied with finding more housing options for the hordes of war workers still coming into the city.[25] 135 soldiers from Camp Meade (which is now Fort Meade) were diverted from more typical preparations of war and sent out to the streets of the District to track down available lodging for war workers.[26] Meanwhile, Dr. Fowler downplayed the threat presented by the flu, “Sleep with the windows open… and you will be in little danger.”[27] Such reassurances were made in the wake of 20 civilians and 74 military cases of the malady confirmed in less than a week.[28]

There was no looking back once October came. Cases steadily ticked upward, and so did deaths. It quickly became apparent that no one was safe from the flu’s steely grip of death.[29] Not only were the young children and the elderly dying from the illness (these demographics typically faced high rates of fatality in other epidemics due to impaired immune systems), but those in the prime of their life — 20 to 40 years of age— were disproportionately affected by the infection.[30] This was not good news for the young female war workers and service members flocking to DC.

One such war worker who succumbed to disease that fall was Genevieve Alexander.[31] A college graduate in a time when countless American women did not make it past high school, Alexander fought for women’s rights as a suffragette.[32] Once the United States entered the First World War, she felt compelled to join the war effort on the home front. Not missing an opportunity to demonstrate the bravery and stamina of women, Alexander walked some 3,000 miles from her home in California to Washington, DC to start her new life as a government employee, all in the hopes of one day turning her experiences into a book.[33] While she made it to the Capital and began her duties with the Food Administration, her life was unceremoniously cut short when she contracted the malady most likely from someone within her living situation at 3055 Q St., NW.[34]

Even prior to the epidemic hitting the city, landlords provided significantly subpar living conditions for the vulnerable war workers. Housing was in short supply and the transplants – who were primarily young women – took what accommodations were recommended to them by the United States Home Registration Service.[35] Desperate for rooms, the government took what it could get from landlords who capitalized on the government’s distress. The result was slum-like conditions in many of the housing options offered to the fledgling civil servants.[36]

Once the flu came to Washington, the crowded, sub-par living conditions were akin to pouring gasoline on a fire. In innumerable situations, tenants reported a lack of heat provided to them.[37] Living in a perpetually cold place severely weakens the immune system, making a person more susceptible to getting sick. On the pages of The Washington Times, the President of the District Board of Commissioners openly pleaded with landlords to improve conditions:

It is extremely dangerous under present conditions not to have heat in apartment houses or homes on chilly mornings. I cannot understand how the most hard-hearted and most shameful profiteers can send his tenets to untimely graves by refusing to furnish heat for the sake of saving a little money off their coal bill. I am sure that such a man, if he exists In the District, will be visited with the condemnation of all right-thinking men and women. I am advised by the District health officer that on cold mornings and evenings heat is necessary. No action beyond this public notice should be needed for the most parsimonious landlord to start his furnace. One case of an apartment house owner refusing to furnish heat, with persons in the apartment ill, has come to my attention. I trust this will be the last and only case so reported. The temperature of living rooms and living apartments should be as near 63 degrees Fahrenheit as possible."[38]

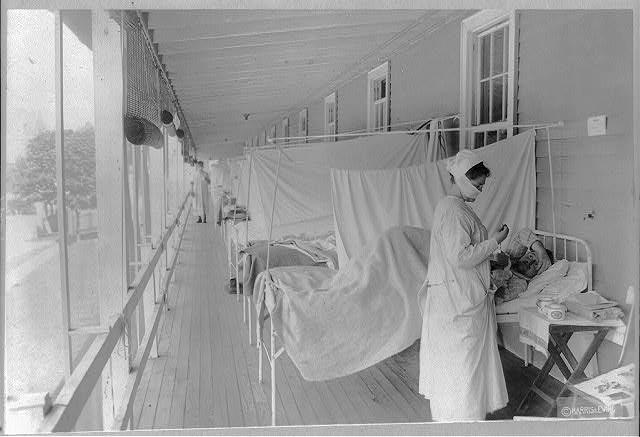

Despite the desperate calls, the poor conditions and overcrowding continued. Across the city, multiple people lived in small rooms, which previously only housed one.[39] If one person contracted the illness, more likely than not, all in the apartment would come down with it as they had nowhere else to go.[40] Scores of war workers were admitted to hospitals around the city as many did not have family in the area to help care for them and – hopefully – nurse them back to health. Fearing further spread, health officials discouraged mothers of female war workers to come to the city to aid with their daughter’s sickness. Existing hospitals were severely overcrowded and increasingly understaffed. D.C. and Federal officials scrambled to find beds for the afflicted and a War Department building at 18th St NW and Virginia Avenue was transformed into a 500 bed influenza hospital.[41]

If lucky, those admitted to the hospital would make it to the convalescent stage. Reaching this point of the illness did not mean they were out of the woods, but rather, they had merely survived the worst part. Given the state of the hospitals, these individuals could not stay once they made it to this stage of the illness (as a means of making room for the newly infected). But these women were still sick. They needed care and a place where they could recover[42] and many callous D.C. landlords discouraged sick tenets from returning to their vacated rooms – a policy that The Washington Times referred to as “chilly.”[43]

In response to the crisis, the Health and Housing Division of the War Department, put out a request for DC residents to open up their homes to the convalescing female war workers.[44] As spokeswoman Susanna Cocroft, proclaimed in The Washington Times, “These girls need fresh air and sunlight and pleasant surroundings while they are recovering.”[45] Cocroft then sought to reassure the public that housing patients would be safe, “the District Health Department informs us that the disease, in the convalescent stage, is not communicable. We have arranged for matrons to take charge of any home or homes that will be turned over to us for this work.”[46]

Notable Washingtonians rose to the occasion. Women like Mrs. Samuel A. Ellsworth of the Y. W. C. A., and Mrs. Herbert Hoover, wife of the Federal Food Administrator (and future First Lady of the United States), opened their homes to the recovering women.[47] The Georgetown estate known as “Castle View” (the home of Mr. and Mrs. Ben Allen) was donated to the Y.W.CA. as a convalescent home as well.[48] Giving up one’s home was not an option for all Washingtonians, especially if they lived in a smaller abode. But many still found ways to lend a hand to the war workers by donating furniture and other necessary items to go inside the homes.[49]

The kindness of DC citizens did not go unreciprocated. Female government workers wanted to do their part for the city, which helped them in their time of need. Individuals like Eleanor Sanford performed her patriotic duties during the day, working as a clerk for the United States Post Office.[50] After working a full day, Sanford packed up her bag at 4 PM and headed down to the Webster School where she moonlighted as a volunteer nurse for the Public Health Service.[51] Sanford was not alone. As The Times noted in October 1918, countless other female war workers followed suit.[52]

The so-called Spanish Flu terrorized the District for six weeks.[53] The city ran out of coffins as reports of the dead mounted, reaching over 3,100 by the time District infections started to wane in mid-November.[54] The timing was, in a way, poetic. Across the Atlantic, the Great War finally ended as well — on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918. The timing prompted a The Washington Times headline to declare “Victory Joy Kills Spanish Influenza.” [55]

Relief, of course, wasn’t quite that immediate. There continued to be flu cases and deaths for several more months. However, by the spring/summer of 1919, the epidemic appeared to peter out.[56] While there was a resurgence in 1920, it was not nearly as deadly as it had been in the Autumn of 1918. (Scientists speculated that the lack of deaths in the 1920 spike was the result of humans being significantly more resistant to the illness after the previous two years.)[57] At last – after years of death and destruction from compounding crises — D.C. and the World could turn the page.

Footnotes

- ^ “The U.S. in WWI,” Worldwar1centennial.org, The United States World War One Cenential Commission, accessedJuly 19, 2022.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Christopher Capozzola, “How World War I Transformed Washington,” Politico.com, Politico Magazine, August 7, 2014.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “No Bar to Influx of War Workers,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), October 8, 1918.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Food Chief Makes Childs Cut Prices,” The Washington Times (Washington, DC). October 2, 1918.

- ^ Carol R. Byerly, Fever of War (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2005), introduction.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Soldier Patients Increase,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), April 25, 1918.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Boston Panicstricken by Spanish Influenza,” The Washington Herald (Washington, DC), September 23, 1918.

- ^ “Move to Check Influenza in D.C.,” The Washington Times (Washington, DC), September 20, 1918.

- ^ “Influenza Kills Here: One Death and Two New Cases Reported," The WashingtonPost (Washington, DC), September 22, 1918.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Influenza Fails to Gain in DC: No New Cases Reported Today to the Health Officer,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), September 24, 1918

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Byerly, Fever of War, “Chapter 3: Worst Case Scenario.”

- ^ Alfred Crosby, America's Forgotten Pandemic (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2003), “Chapter 2: The Advance of the Influenza Virus.”

- ^ Ibid, “Chapter 4: The United States Begins to Take Note.”

- ^ “Soldiers to Make Rooming Canvas,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC) September 25, 1918.

- ^ “Soldiers Find 800 Rooms a Day,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC) September 28, 1918.

- ^ “Spread of Influenza here; Cause for Alarm Denied,” The Washington Post (Washington, DC), September 27, 1918.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Seven Die of Epidemic,” The Washington Post (Washington, DC), October 1, 1918.

- ^ Byerly, Fever of War, introduction.

- ^ “Suffragette War Worker Who Walked Here from California Dies of Flu,” The Washington Times (Washington, DC). October 24, 1918.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid. Although the Food Administration contacted Alexander’s family about her death, The Times reported that no one had claimed her body. It is unclear whether anyone ever did but this notion highlights the heartbreaking circumstances of war workers who passed without their families around them and still faced the effects of their distance from their homes even after they were gone.

- ^ “Soldiers to Make Rooming Canvas.”

- ^ “Landlords Are Warned by Brownlow to Heat Apartments They Rent,” The Washington Times (Washington, DC). September 9. 1918.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ John Kelly, “1918, the Year a Flu Caused an Epidemic of Terror,” The Washington Post (Washington, DC), January 22, 2004.

- ^ “Group of Eight Ill from Influenza,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), October 12, 1918.

- ^ “Flu Epidemic Here Well in Hand Says Surgeon General Blue,” The Washington Times (Washington, DC), October 17, 1918.

- ^ “Seek Homes for Flu Survivors.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Castle View Is Changed Into a Convalescent Home for Girl Workers,” The Washington Post (Washington, DC), October 16, 1918.

- ^ “Plea Made for Furniture,’ The Evening Star (Washington, DC), October 19, 1918.

- ^ “War Workers Give Nights to Nursing,” The Washington Times (Washington, DC), October 28, 1918.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Kelly, “1918, the Year a Flu Caused an Epidemic of Terror.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Victory Joy Kills Spanish Influenza,” The Washington Times (Washington, DC), November 17, 1918.

- ^ Crosby, America's Forgotten Pandemic, “Chapter 11: Statistics, Definitions, and Speculation.”

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)