March 1981: The Tourist From Hell

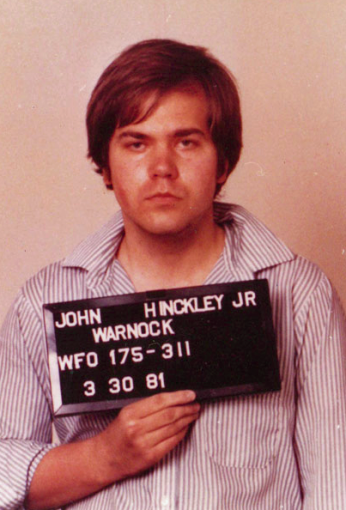

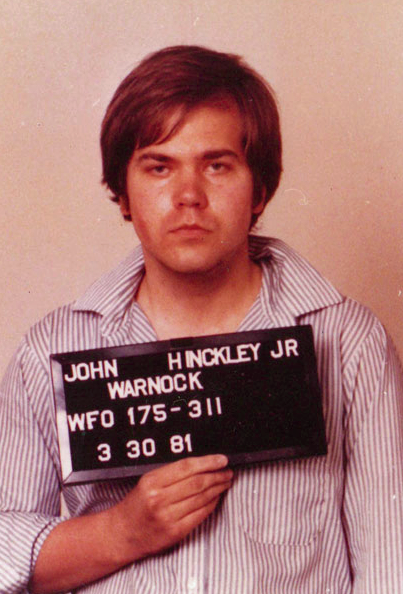

As the sun rose over Washington, DC, on the morning of March 30, 1981, in room 312 of the Park Central Hotel on 705 18th Street NW, a guest lay in bed, anxious and wired after a mostly sleepless night. He had arrived the night before on a Greyhound bus, and like many other tourists who visit Washington from afar, he had a big day ahead. But unlike most of them, he didn't plan to see the Lincoln Memorial or the Capitol dome, or to peruse the exhibits at the Smithsonian Institution's various museums. No, this visitor had something different in mind. His name was John Warnock Hinckley, Jr., and he was going to try to kill the President of the United States.

The room itself came into focus. The Park Central wasn't one of Washington's finer hotels, but for $47 a night, it was affordable, if a little dreary, with its brown carpet and the cheap-looking floral comforter on the bed. Nearby was a tan suitcase, whose contents later would be carefully catalogued by FBI agents. According to a report later compiled by the U.S. Justice Department, among other items, it contained: An assortment of shorts mostly purchased at J.C. Penney, a pair of undershorts, shoe laces, a used airline ticket, a studio pass to see the taping of the Merv Griffin Show on March 26, and a pocket Instamatic camera containing a 24-frame roll of film, though Hinckley had taken no pictures with it. Hinckley, who was just about two months shy of his 26th birthday, had been roaming the country restlessly for months, riding buses and staying in shabby motels, and apparently the grueling travel had taken its toll, as evidenced by the bottle of Doan's Pills for backaches and a partially-used roll of Di-Gel antacids. A red-and-black plaid suitcase contained more clothing, in addition to a couple of visitor's passes to the U.S. Senate

Ominiously, there was also the black box that contained his .22 RG Industries revolver, along with an instruction manual, and an assortment of ammunition, including 35 hollow-point shells.

Like other travelers, Hinckley had brought some reading material to pass the time. He had a copy of J.D. Salinger's Catcher in the Rye, and a book on serial killer Ted Bundy, and another entitled Strawberry Fields Forever: John Lennon Remembered, about the Beatle who had been slain just a few months before. The would-be songwriter also had a book on how to market his compositions. He also had a copy of the October 1980 issue of Esquire magazine, which contained an article that Jodie Foster had written about leaving Hollywood to attend Yale University. Hinckley was obsessed with Foster, but his letters to her had gone unanswered. As United Press International later reported, his possessions also included a cassette recording of two phone calls that he had made to Foster at Yale. ("Do me a favor and don't call back. All right?'' the actress had told him.) A few years before, Foster had appeared in the movie Taxi Driver, in which the title character--portrayed by Robert Di Niro--had made an aborted attempt to kill a politician. Now, in a twisted effort to impress Foster, Hinckley would follow that fictional template.

At approximately 8:00 a.m, according to the Justice Department report, Hinckley left the hotel and had breakfast alone at a sandwich shop. On the way back to the hotel, he picked up a copy of both the Washington Post and its then-competitor the Washington Star. Back in the room, he turned to the Star, and saw that President Ronald Reagan would be at the Washington Hilton on 1919 Connecticut Avenue N.W. to deliver a speech to an assembly of AFL-CIO members. That was welcome information to Hinckley. When he'd arrived in Washington the previous afternoon, he'd gone to the White House, and stood near the fence on the South Lawn. He asked some nearby tourists if the President was in town, and where somebody could go to see him. The tourists didn't really know--they'd suggested, naively, that Hinckley might be better off standing in front of the White House. But now he knew exactly where Reagan would be, and when.

Back at the hotel, he sat down at 12:45 p.m. and composed one last letter to Foster on a lined sheet of yellow paper. It began: "Dear Jodie, there is a definite possibility I will be killed in my attempt to get Reagan."It continued: "Jodie, I would abandon the idea of getting Reagan in a second if I could only win your heart and live out the rest of my life with you, whether it be in total obscurity or whatever. I will admit to you that the reason I'm going ahead with this attempt now is because I cannot wait any longer to impress you. I've got to do something now to make you understand, in no uncertain terms, that I'm doing all of this for your sake! By sacrificing my freedom and possibly my life, I hope to change your mind about me. This letter is being written only an hour before I leave for the Hilton Hotel. Jodie, I'm asking you to please look into your heart and at least give the chance, with this historical deed, to gain your love and respect." Then he left the hotel and hailed a cab to take him to the Hilton.

At 1:50 p.m. according to the Justice report, Hinckley was in the crowd of approximately 285 people standing behind a rope barrier a short distance from the Hilton's VIP entrance. He had $129 in his wallet and in the right pocket of his tan jacket, he had his revolver. He waited. At 2:25 p.m., sure enough, the President and his entourage, which included his press secretary James Brady, exited the building and walked toward the Presidential limousine. Hinckley had positioned himself just 15 feet from the car. He pulled out his .22 revolver, and fired six times.

The first person he hit was press secretary Brady, who took a bullet to the head and crumpled to the ground. The next shot hit District police officer Thomas Delahanty in the back of his neck, as he turned to shield Reagan. A third shot went over the President's head, and a fourth hit Secret Service agent Timothy McCarthy in the abdomen. The fifth shot hit the limousine window. One more shot left. Hinckley missed, again hitting the limousine, but the bullet ricochetted and hit Reagan under his left arm, grazing a rib and lodging in his lung, about an inch from his heart.

Suddenly, Hinckley found himself being punched and slammed against the wall, as the President was rushed off to George Washington University Hospital for treatment. (Del Quentin Wilber's 2012 book Rawhide Down: The Near Assassination of Ronald Reagan, gives a detailed account of the effort to save the President's life.)

Hinckley had failed. Reagan recovered from his injuries but Brady was left largely paralyzed and went through years of struggle before dying in August 2014. Hinckley was tried and found not guilty by reason of insanity in 1982, and was remanded to St. Elizabeths psychiatric hospital in Southeast DC. He was released from prison in 2016.

WETA looks back at the people and events of the 1980s in a one-hour documentary, Washington in the '80s.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)