Encore: How the Tivoli Theater Became the Epicenter of a Debate over Urban Renewal

“The Tivoli Theater, a tarnished jewel from 14th Street’s past, awaits resurrection or the wrecking ball–a simple, straightforward choice. Or so it would seem.”[1]

In 1983, Washington Post reporter Benjamin Forgey’s words reflected the complex debate that was swirling around the Columbia Heights neighborhood. Should the Tivoli Theatre, a once magnificent movie palace from the Golden Age of movies, be restored as an entertainment space, preserving its history, or should it be partially demolished to make way for necessary additions to the neighborhood? The question split residents and led to a years-long real estate battle.

The Tivoli Theatre, a part of D.C. movie theater magnate Henry Crandall’s empire, opened in 1924 with a parade dancing from Pennsylvania Avenue to Columbia Road and a carnival full of street performers welcoming people at the door.[2] Tickets to the opening day showing on Saturday April 5, 1924, sold out within three hours of being put on sale on April 3.[3] One Washington Post article described the theater as “...largest and most beautiful playhouse in the National Capital,” and declared that it would “...exert a city-wide appeal to those who respond to superlative enjoyment provided in an atmosphere of beauty and artistry.”[4] The Tivoli was designed by Thomas White Lamb, one of the most prominent theater architects at the time, who made the Tivoli both beautiful and functional.[5] Its orchestra pit and organ, hallmarks of silent film theaters, were unique due to their attachment to elevators which could render them visible or invisible.[6]

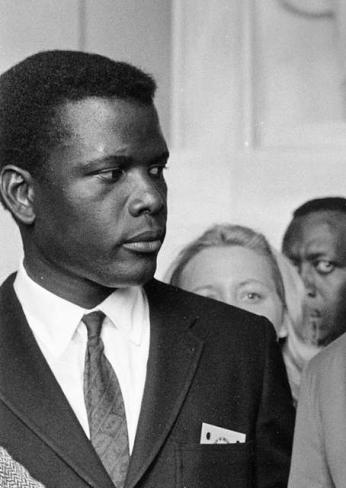

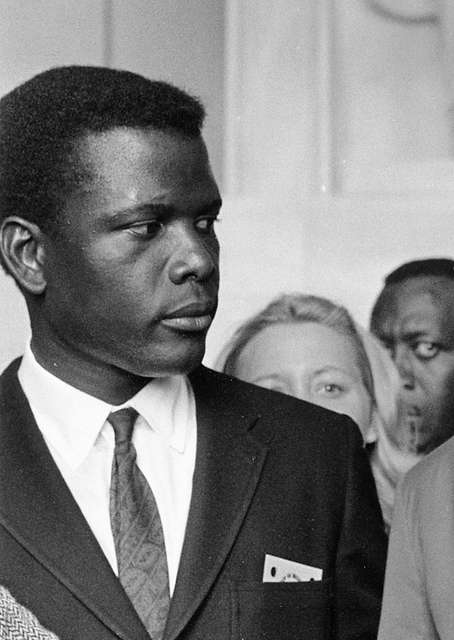

Though the Tivoli was a cultural phenomenon, it was not accessible to everyone. Black Washingtonians were not allowed to attend movies at the Tivoli until 1954, when D.C. began to integrate on a large scale after the passing of Brown v. Board of Education. That history would become a sore spot for some as the neighborhood’s demographics began to change. But by the late 1950s, the Tivoli had become a centerpiece for the Black community in Columbia Heights, though African American patrons were restricted to the balcony.[7] Mack James, one of the Advisory Neighborhood Commissioners for Ward 1 from 2003 to 2004, recalled: “Coming to the Tivoli back then, it was really great. 25 to 30 cent was all it cost and you see two movies all day long.”[8] In 1963, the NAACP and other local civil rights organizations held a fundraiser at the Tivoli to screen the film “Lilies of the Field,” a movie starring legendary actor Sidney Poitier, who himself showed up at the demonstrations to show his solidarity.[9] This event was part of a pushback against the theater for only allowing Black moviegoers to sit in the balcony and resulted in them gaining access to orchestra seats.[10]

Over time, Columbia Heights became a destination for black patrons and some even compared it to U Street, a neighborhood lovingly known as ‘Black Broadway’ for its rich history of African American clubs and music venues.[11] Unfortunately, everything changed in 1968. The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. hit the nation hard, and in D.C. riots broke out throughout the city. Columbia Heights was particularly hard hit, with many storefronts destroyed. Though the Tivoli survived, it slowly began to fall into disrepair and officially closed its doors in 1976 – one of many changes happening in the neighborhood.[12] By the 1970s, there were only two supermarkets serving Columbia Heights, which fueled discussions about ‘urban renewal’ that would test the neighborhood in the 1980s. Washington Urban League president Larry F. Weston appraised the area’s prospects bluntly, “This is not a fictionalized idealized community like Camelot or Lake Wobegon. It is a neighborhood with a history of underdevelopment and economic neglect. It is not a viable neighborhood right now.”[13] The Tivoli became a touchpoint as the community, the city, and developers debated competing visions for Columbia Heights' future.[14]

In November 1979, the D.C. government’s Redevelopment Land Agency (RLA) asked potential developers to propose a “complete new development” of the Tivoli which stipulated that the theater would be demolished unless essential to the project.[15] The RLA chose a group of developers known as Park Central Associates Corporation in 1981, and approved their plan to restore the lobby of the Tivoli while destroying the rest, to make room for a series of office and commercial spaces including a Safeway and a parking lot.[16] “There’s no question you’re sitting on a gold mine there,” A person familiar with the area said.[17]

That may have been true – especially considering that the Metrorail Green Line would eventually have a stop in Columbia Heights – but federal officials warned developers that the Tivoli might qualify as a national landmark under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966.[18] This decision caused conflict amongst the residents of Columbia Heights. Some, who did not want to see the building demolished, formed a grassroots organization known as Save the Tivoli Inc. Others saw the benefit in having a third grocery store in the neighborhood and hoped that more investment in Columbia Heights would help improve their lives.

Despite the RLA’s actions, the Tivoli’s destruction was not set in stone. On July 1, 1983, the now defunct D.C. Joint Committee on Landmarks designated the Tivoli as a local landmark. A Post article from the time read, “The Joint Committee, which oversees the city’s historic buildings and districts, ruled that the 62-year-old Tivoli, one of only two old-time movie palaces left in the District, has important historical significance and, if possible, should not be torn down.”[19] That same year, Save the Tivoli challenged the project in US District Court to block the demolition, which resulted in the RLA submitting a federal review, which would take until 1987 to complete.[20]

The conflict took another twist in March 1985 when the D.C. government changed direction. Facing a threat that federal historic preservation funds totaling $228,000 would be cut off, the District asked that the Tivoli be registered as a national historic landmark.[21] The decision infuriated developers. As J. Gerald Lustine vented to the Post, “They must have lost their minds. We’re trying to build a store up there. We can’t build anything if the building stays.”[22] Eric Graye, president of Save the Tivoli, had a much different perspective. “Better late than never. They have finally done it, but only under our pressure.”[23]

A little less than a month later, on April 10, the Tivoli was put on the National Register of Historic Places. While this didn’t mean that it couldn’t be demolished, the designation would give developers a 25% tax credit for renovating the building if the renovation met federal guidelines.[24]

Even with the incentives, full restoration would be a tough sell. A 1983 study had found that a complete renovation of the Tivoli would cost over 10 million dollars, an amount that the developers weren’t eager to pay, especially considering the likelihood that a fully restored theater would operate at a deficit.[25] Lustine explained that the city had two choices “You can take what we want or leave it there for another 20 years as it is. I just cannot imagine anyone touching that building for economic reasons. You can’t save the whole building.”[26] After the federal review was completed, the decision moved to the zoning board.

On April 15, 1989, a 3-to-2 vote by the D.C. Zoning Commission awarded Park Central Associates temporary approval for the Tivoli redevelopment project, allowing for a commercial rezoning of the area previously reserved for residences. The commission had initially rebuffed Park Central Associates plan for fear that the firm would eventually replace the dearly needed supermarket with more lucrative office space. However, a compromise was reached to put legal covenants on the land to prevent such a scenario.[27] Not all were pleased by the compromise, however. Lindsley Williams, one of the dissenting members, argued that “I think the commission will come to rue the day that it engaged in this process.”[28] Unfortunately, on December 2, 1989, one of Columbia Heights' two supermarkets closed. This closing increased pressure on the Tivoli project, as the only remaining supermarket in the neighborhood suffered from overcrowding.[29]

Despite the added pressure, the project continued to stall. Meanwhile, the demographics of Columbia Heights were changing. Though the neighborhood was still predominantly Black and Latino, more affluent white professionals began trickling in after being priced out of DuPont Circle and Georgetown.[30] In 1993, the stakes were upped once again in a conflict over whether to close a system of interconnected alleys. Those in support of the project wanted to close the bisecting alleys in order to see the project finally begin, but others pushed back, still upset at the commercial rezoning of the land behind the Tivoli. Residents were divided, with some determined to save the Tivoli and restore it to be an entertainment center and others who had no interest in a building that would not let them enter until the 1950s, instead focusing on the dearly needed supermarket.[31]

Three years later, with construction of the green line Metro stop well under way, there was still no change in sight for the Tivoli. The Post noted that though the neighborhood had long been home to many middle-class African Americans, the influx of Latino and Asian immigrants and the increase of students and artists looking for older houses to save money by living together. Despite the disruptive construction, and the lack of economic investment in the neighborhood, many long-time residents still held out hope for revitalization.[32] Delores Tucker, a lifelong Columbia Heights resident, explained: “The train of thought is that once you leave here, you’ll never be able to afford to come back.”[33] After years of inactivity, the District terminated the deal they had with Park Central Associates in 1998 and opened the floor for new bids.[34]

Three new developers threw their hats into the ring: Cleveland-based Forest City Enterprises, local construction company the Horning Brothers, and New York developer Grid Properties.[35] The Forest City Enterprises plan was popular amongst residents who supported the complete preservation of the Tivoli, as their more comprehensive plan closely mirrored the two years of planning done by members of the community. Despite its popularity, though, the RLA decided to go with the plans of the Horning Brothers and Grid Properties, upsetting those who campaigned for Forest City.[36] The other projects, which gained approval in 1999 were the Horning Brothers $18 million plan to restore the façade and lobby of the Tivoli, adding 40,000 square feet of retail inside, with a Giant Foods attached at the rear of the building and 29 town houses at the site and Grid Properties $131 million plan to build an entertainment complex across the street.[37]

The RLA’s approval was not enough to stop the continuing conflict. After the Horning Brothers’ (a company led by brothers Joe and Larry Horning) bid was accepted, suddenly D.C. officials questioned the awarding of the deal and tried to revoke it, resulting in an 18-month tussle that ended in the Horning Brothers signing a 99-year deal to lease the land from the city for development. The fight was not over yet though. Save the Tivoli filed a lawsuit in 2001 to try to preserve the theater’s stucco walls –an impossible task according to the Horning Brothers.[38] Joe Horning explained that if he preserved the interior, costs would jump so high that rents would be at prohibitive levels.

So, he proposed a compromise. The interior of the old movie house would be split into offices, retail, and a theater. To make it happen, Horning would put up $16 million of his own money and secure an additional $16 million loan from Riggs Bank. The D.C. government would need to chip in $8 million.

It was an attractive offer, and Horning explained that having a cultural element to the project was important to him: “I saw doing the Tivoli as a unique opportunity to blend residential with retail and to do something for the community. It’s a rare opportunity to combine both.”[39] Negotiations took more than two years but the issue was settled.[40]Though the solution did not please everybody, it brought an end to a decades long conflict and many Columbia Heights residents, such as Terry Lynching saw it as a step forward for their neighborhood. “We all have every finger and toe crossed that at last this is actually happening.”[41]

In January 2005, the Tivoli finally opened, heralding the “revival of the Columbia Heights neighborhood,” according to Post writer Debbi Wilgoren.[42] The performance space became the permanent home to GALA Hispanic Theatre, which pleased theater owners Rebecca and Hugo Medrano greatly. As Medrano told the Post, “This is wonderfully convenient for us, because we’ll have our offices and theater all in one place.”[43] Perhaps more importantly, the location put the GALA close to the District’s biggest Latino neighborhoods.

Along with the opening of the Tivoli, 10 more projects dedicated to the renewal of the Columbia Heights neighborhood, including several apartment complexes and the District’s first Target were either beginning or underway.

Christopher J. Donatelli, whose construction firm was working on the residential-retail projects, noted that “The impact is going to be huge. If you left for a year or two and then came back, you might not recognize it.”[44] Though members of the community were nervous about the possibility of rising rents pricing them out of their homes, D.C. Council Member for Ward 1 Jim Graham remarked that: “This is a neighborhood that, just a short time ago, we couldn’t get fast food into. And now it will have everything. There are tensions, but the mix is good.”[45] The future may have been unclear, but one thing stood out – the conflict over the Tivoli was finally over.

Footnotes

- ^ Benjamin Forgey. "A Landmark Case: Why the Tivoli Theater should be Saved the Tivoli Theater: A Tarnished Jewel." The Washington Post (1974-), Jun 04, 1983 (accessed July 9, 2022).

- ^ Ghosts of DC. “If Walls Could Talk: Tivoli Theater was the “Temple of the Arts.” Ghosts of DC. Ghosts of DC. April 16, 2012.

- ^ Homa, Shannon. “Tivoli Theater: Telling Compelling Stories since the 1920s.” 826DC. 826DC. October 24, 2016.

- ^ "BIG THEATER OPENS HERE ON SATURDAY: NEW TIVOLI, LATEST OF THE CRANDALL CHAIN, HAILED AS THE LARGEST AND MOST, BEAUTIFUL PLAYHOUSE." The Washington Post (1923-1954), Mar 30, 1924, (accessed July 9, 2022).

- ^ “Tivoli Theatre,” DC Historic Sites, accessed July 9, 2022.

- ^ "New Tivoli Theater Finest of the Fine." The Washington Post (1923-1954), Feb 24, 1924, (accessed July 9, 2022).

- ^ WETA Extras. “Tivoli Theater.” WETA. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Aired February 15, 2005.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ "Seats in Orchestra are Won by Negroes." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Sep 22, 1963, (accessed July 9, 2022).

- ^ WETA Extras, “Tivoli Theater.”

- ^ DEBBI WILGOREN Washington Post, Staff Writer. "Curtain Up again in Columbia Heights: Neighborhood Copes with Development as Restored Theater Reopens." The Washington Post (1974-), Jan 09, 2005, (accessed July 9, 2022).

- ^ David S. Hilzenrath, Washington Post Staff. "Development Battle Spotlights Tivoli Theater: Development Battle Puts Tivoli in Spotlight." The Washington Post (1974-), Jul 09, 1988, (accessed July 9, 2022).

- ^ "City Wants Old Tivoli Theater for Cardozo Community Hall." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Apr 04, 1969, (accessed July 9, 2022).

- ^ Hilzenrath, “Development Battle Spotlights Tivoli Theater.”

- ^ Along with the Tivoli, five other neighboring city-owned properties were also up for redevelopment per the agreement reached between the developers and city council. Source: Hilzenrath, “Development Battle Spotlights Tivoli Theater.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ "Old Tivoli Theater Declared Landmark." The Washington Post (1974-), Jul 02, 1983, (accessed July 9, 2022).

- ^ Hilzenrath, “Development Battle Spotlights Tivoli Theater.”

- ^ Kenneth Bredemeier Washington Post,Staff Writer. "Historic Rank Asked for Tivoli: Developers Oppose Listing for Theater Historic Status is Asked for Tivoli Theater." The Washington Post (1974-), Mar 19, 1985, (accessed July 9, 2022).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Kenneth Bredemeier Washington Post, Staff Writer. "Tivoli Makes Historic List: Fate Still Uncertain." The Washington Post (1974-), Apr 11, 1985, (accessed July 9, 2022).

- ^ Hilzenrath, “Development Battle Spotlights the Tivoli Theater.”

- ^ Bredmeier, “Tivoli Makes Historic List.”

- ^ "REAL ESTATE NOTES: ZONING BOARD BACKS TIVOLI DEVELOPMENT PLAN." The Washington Post (1974-), Apr 15, 1989, (accessed July 9, 2022).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Thomas Bell Washington Post, Staff Writer. "Safeway Closing Refuels Fight: Neighbors Want to Save Tivoli Theater Building." The Washington Post (1974-), Jan 04, 1990, (accessed July 9, 2022).

- ^ Wilgoren, “Curtain Up Again in Columbia Heights.”

- ^ Harris, Hamil. "Alley's Status at Stake in Theater Dispute." The Washington Post (1974-), Jul 22, 1993, (accessed July 26, 2022).

- ^ Dana Hull Washington Post,Staff Writer. "Amid the Turmoil, Columbia Heights Struggles to Revive." The Washington Post (1974-), Aug 24, 1996, (accessed July 26, 2022).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ DANA HEDGPETH Washington Post,Staff Writer. "Drama before Curtain Call at Theater." The Washington Post (1974-), Oct 04, 2004, (accessed July 26, 2022).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Brizill, Dorothy A. "Rebirth for Columbia Heights: A Difficult Labor: Why Doesn't the City Listen to the Community?" The Washington Post (1974-), Nov 21, 1999, (accessed July 26, 2022).

- ^ Pyatt, Rudolph A. Jr. "Tussling Over the Tivoli Theater Becomes A Bad Scene for Columbia Heights." The Washington Post (1974-), Oct 21, 1999, (accessed July 9, 2022)

- ^ Hedgepeth, “Drama before Curtain Call at Theater.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ NEIL IRWIN Washington Post,Staff Writer. "Historic Tivoli Theater Ready for its Close-Up." The Washington Post (1974-), May 12, 2003, (accessed July 9, 2022).

- ^ Wilgoren, “Curtain Up Again in Columbia Heights.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)