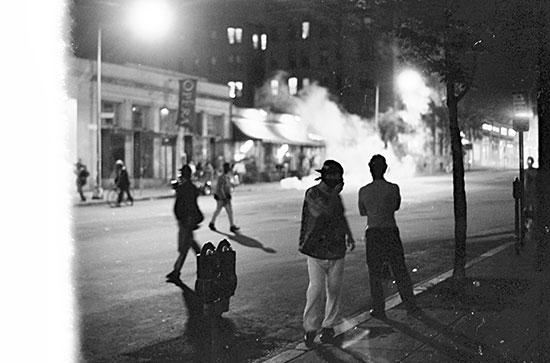

Mount Pleasant Boils Over, 1991

Angry mobs clashing with police… Looting… Flames…. It was a scene out of the 1968 riots. But this was a different time and place. The year was 1991 and D.C.’s Mount Pleasant neighborhood was boiling over.

The firestorm started at around 7pm on the evening of May 5. Angela Jewell and Girsel Del Valle, rookie cops from the Metropolitan Police Department’s 4th District, were out on patrol in the neighborhood. They approached a group of men who appeared to be drinking in public at 17th and Lamont Streets, NW. Angry words were exchanged and the men supposedly became disorderly. The officers began to make arrests.

What happened next was the source of some debate.

According to a police spokesman, one of the men, 30-year-old Daniel Enrique Gomez, drew a knife and lunged at Officer Jewell. In an effort to defend herself, she fired her weapon, critically wounding Gomez in the chest.

But some bystanders in the predominantly Latino community presented a far more disturbing version of events: that Gomez had been shot when he was already in handcuffs.

The incident sparked immediate outrage in the community. Crowds took to the streets and pushing and shoving soon led to flying rocks and bottles. Demonstrators overturned several cruisers and set them on fire as MPD officers called for reinforcements. In the words of one witness, “all hell broke loose.”[1] Around midnight a crowd broke into a 7-11 store at Mt. Pleasant St. and Kenyon St. At 18th and Columbia Road in neighboring Adams Morgan an Up Against the Wall clothing store was looted.

Many in the city government were caught off guard. As D.C. Councilmember Frank Smith, Jr. remarked, the chain of events pointed to larger fissures in the community, “This takes me by surprise; its magnitude concerns me very much. This is an intimation of the flashpoints in the community.”[1]

The biggest flashpoint was the strained relationship between the city’s primarily white and black police force and the Latino residents of the Mount Pleasant neighborhood. Quite literally, they did not speak the same language and there was considerable distrust on both sides.

As one resident told the Post in the days after Gomez’s shooting, “We are oppressed by the police. If you look Spanish or speak Spanish, they’re suspicious of you.”[2] Another added, “This explosion has been brewing for a long time. If you live here, you see a lot of abuse by police.”[3]

Columnist William Raspberry saw a connection to 1968. “The parallels between the Latino communities and riot-torn black communities of the ‘60s are striking. The same substandard, overcrowded housing; dreary, poorly paid jobs (or no work at all); the same resentment on the part of neighbors, the same voicelessness, the same complaints of police brutality. And the same feeling that nobody cares.”[4]

Given the history, it’s no surprise that police struggled to get the situation in Mount Pleasant under control. After rain showers helped bring a short-lived calm to the area, roving packs of youth clashed with police again the following night.

Multiple businesses were looted including a Safeway on Columbia Road and a Giant Food Store on 14th Street as the disturbances expanded beyond Mount Pleasant. Protesters torched a Church’s chicken fast food restaurant. On 16th St., a crowd boarded a Metrobus and set it ablaze, one of a number of vehicle fires in the neighborhood. Police countered with tear gas and other non-lethal measures to disperse the crowds, but had trouble wrangling the protesters.

As the unrest wore on, observers noted a shift. “Sunday night’s rage, triggered by the shooting and focused sharply on the police by Hispanic residents, gave way Monday to an unfocused free-for-all by teenagers and young men in their early twenties. Rather than guns, they carried an anger relieved only by breaking and taking things.”[5]

In response, Mayor Sharon Pratt Dixon – who many had criticized for being slow to react to the emergency – instituted a nighttime curfew in Mount Pleasant, Adams Morgan and Columbia Heights. Businesses were expected to close and residents traveling to and from work would have to show identification in order to be on the streets. Violators risked fines of $300 or 10 days in jail. (The curfew started out as midnight - 5am and was later expanded to 7pm - 5am.)

The mayor also announced a change in approach to law enforcement. After initially telling police to disperse crowds but not make any arrests, which she feared might further strain relations with the community, Dixon changed tactics. Saying that the situation was “not as contained as it needs to be,” she announced, “We’re going to have to be more aggressive. We’re going to cordon off the area and we’re going to arrest them now.”[3]

Fearing further violence, some business owners along the commercial strips began boarding up their windows like you might see before a hurricane. A few Latino community leaders walked with the police on patrol in hopes of keeping the peace.

Fortunately, the combination of tactics had the desired result. After a third night of unrest, the violence dissipated over the following days. By week’s end the mayor lifted the curfew.

While there were some injuries (primarily to police officers) and significant property damage, no one was killed in the riots, a fact which MPD Chief Issac Fulwood celebrated: “Our whole idea from Day One was to use a minimum of force. That’s why we haven’t had any persons killed in this community.”[6]

But even as law enforcement put a positive spin on the city’s response to the unrest, it was clear that D.C. faced new challenges. As Council Chairman John Wilson reflected, “We’ve learned a lot of things in the past week. We learned that the city is changing. That the government had better have better communication with all segments of the city. That the militancy of our young is at its highest ebb. That the poor of this city are extremely frustrated.”[7]

For photos of the riots, see Secorlew's gallery on Flickr and the Telemundo news report below. Also, check out the great 2011 audio story by WAMU's Emily Friedman, which includes interviews with police and community members who experienced the Mount Pleasant riots first-hand.

Footnotes

- a, b Lewis, Nancy and James Rupert, “D.C. Neighborhood Erupts After Officer Shoots Suspect,” The Washington Post, 6 May 1991: A1

- ^ Castaneda, Ruben and Nell Henderson, “Simmering Tension Between Police, Hispanics Fed Clash,” The Washington Post, 6 May 1991: A1.

- a, b Sanchez, Carl and Rene Sanchez, “ Dixon Imposes Curfew on Mount Pleasant Area As Police, Youths Clash for a Second Night,” The Washington Post, 7 May 1991: A1.

- ^ Raspberry, William “Grim Reruns of the ‘60s,” The Washington Post, 8 May 1991: A31.

- ^ Henderson, Nell, “‘We’re Angry ‘Cause of Being Hassled,’ Youths Say,” The Washington Post 8 May 1991: B1.

- ^ Spolar, Christine and Mary Ann French, “Dixon Moved Cautiously In Effort to Restore Calm,” The Washington Post, 8 May 1991: A1.

- ^ Spolar, Christine, “The Painful Lessons of Mt. Pleasant,” The Washington Post, 12 May 1991: A1.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)