How a Failed German Spy Mission Turned into J. Edgar Hoover’s Big Break

On June 13, 1942, four Nazi spies disembarked their U-Boat on a beach near Long Island, New York. Four days later, a similar group landed on Ponte Verda Beach, Florida. Their goal: to harm American economic targets in the hope of turning the war back in favor of Germany. The men had been extensively trained at a sabotage school near Berlin and carried enough explosives, primers, and incendiaries to support two years worth of destruction. They carried plans with them that outlined attacks of New York’s Hell Gate Bridge, hydroelectric plants at Niagara Falls, aluminum plants in Philadelphia, the canal lock systems in Cincinnati and St. Louis, and other targets.[1]

The mission, coined Operation Pastorius after the leader of the first group of German immigrants to the United States, went awry from the very beginning. After the Long Island crew had landed and buried four boxes of sabotage material, they ran into John Cullen, a young member of the Coast Guard on duty that night. The men had been instructed to dress in German uniform so that if they were caught it would be as prisoners of war rather than spies, so Cullen immediately suspected something was up. The leader of the group, George John Dasch, quickly bribed him with $260 to keep his mouth shut. Despite this, Cullen reported what he saw to the authorities, but by the time they were alerted the spies had already escaped to New York City.[2]

The mission seemed to be back on track. But, within a few days Dasch deviated from the plan and traveled to Washington. After checking into the Mayflower Hotel on June 19, he called the FBI from room 351, revealed his identity, and asked to speak with FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.

The call, first regarded as a prank, soon led FBI agents to pick up Dasch at the Mayflower and transfer him to the Department of Justice. While he didn’t get a chance to confess to Hoover himself, Dasch recounted his landing in New York (a detail that the FBI had taken note of thanks to Cullen, yet one that had not been released to the public) and presented the $82,350 the Nazis had given him.[3] Clearly, it was no prank. Agents prodded the German for more information.

Over the next several days, Dasch revealed the identities of the others involved, as well as a handkerchief with addresses written in invisible ink that would prove to be useful in their capture. The remaining members of the Long Island crew were arrested in New York City on June 20th, two of the Florida group were found in the City on the 23rd, and the final two were picked up in Chicago on June 27th. FBI officials also uncovered electric blasting caps, pen and pencil delay mechanisms, ampoules of acid and other tools that were to be used for the mission.[4] All eight spies declared their guilt.

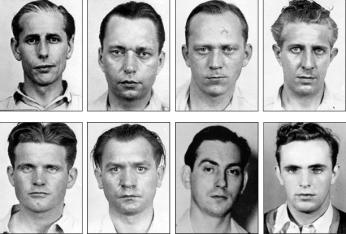

The eight Nazi spies: George John Dasch, Ernest Peter Burger, Heinrich Harm Heinck, Richard Quirin, John Kerling, Werner Thiel, Herbert Hans Haupt, and Herman Otto Neubauer. (Photo source: FBI)

What happened next was a classic Washington spin job. The information about the case was skewed when it was first released to the press on June 28th. There was little mention of Dasch’s confession. Rather, the spies’ capture was hailed as an effort of the FBI spearheaded by Hoover. He had decreased in popularity over the past years and took the chance to capitalize upon the German spies who had fallen into his lap. When it was mentioned at all, Dasch’s role in unraveling the plot was greatly minimized, as evidenced by the Washington Post’s simplistic account of the case, which stated only that Dasch “cooperated with United States officials in procuring evidence against the others.”[5] In fact, his full confession was completely unknown to the public until 1945, when the impact of the events had already faded and Hoover had become a superhero in American society. Hoover didn’t even include the fact that Dasch confessed in a letter he wrote to President Roosevelt informing him of the capture![6]

For obvious reasons, the trial of these German saboteurs was not like any other. It was the first invasion of American soil from enemy vessels in 125 years. And in a proclamation dating July 2, 1942, President Roosevelt decreed that Dasch and his fellow spies “be subject to the law of war and to the jurisdiction of military tribunals.”[7] This was the first time a military tribunal had been used since the Civil War, and there was little doubt that the spies would be condemned to death.[8] The trial began in a converted room in the Department of Justice on July 8th, and by August 3rd the seven military generals of the tribunal found all defendants guilty.

With this ruling, those who were aware of Dasch’s integral role apparently grew uncomfortable with the idea that the man who had hand-delivered the case to the FBI would be executed. In one account, even Hoover, in the midst of celebrating his great triumph over German espionage, believed Dasch’s sentence should be lessened.[9] Shortly after the case closed, Attorney General Francis Biddle appealed to President Roosevelt that Dasch not receive the death penalty. Roosevelt spent five days pondering the matter.

In the end, Dasch was given only a 30 year prison sentence due to his “assistance to the Government of the United States in the apprehension and conviction of the others.”[10] Another spy, Ernest Peter Burger, was given a life sentence for his aid in obtaining the Florida spies. The other six – Richard Quirin, Heinrich Harm Heinck, John Kerling, Werner Thiel, Herbert Hans Haupt, and Herman Otto Neubauer – were condemned to the electric chair.

The lights of the District of Columbia Jail were turned out the morning of August 8th when the spies were put to death. Officials worried that the chair, a relatively new punishment in Washington, would cause the lights to flicker or dim. Each execution took about 14 minutes, so that the whole ordeal was over in about an hour and a half.[11] For the rest of the war, no similar German sabotage effort was uncovered and many came clean as a result of Operation Pastorius. And who took major credit for these facts? You guessed it: Hoover.

Dasch and Burger were freed from prison and sent back to Germany in 1948 by Attorney General Tom C. Clark. The Department of Justice stated that the men had been sufficiently punished, even after just 6 years in jail. Their legend quickly faded, though Dasch attempted to set the record straight in a self-defending memoir 11 years later. In describing his decision to come to Washington and confess, he claimed his motive was genuine: loyalty to the U.S., a country he called his own, having lived in the states for 19 years prior to the war.[12] But, for the most part, the memoir flew under the radar. Those who read it believed Dasch to be “just another Nazi” who got what he deserved.[13] Meanwhile, Hoover’s reputation flourished and, largely because of these lesser-known German spies, he became synonymous with the modern-day FBI.

Footnotes

- ^ “FBI Captures Eight Saboteurs Landed in US by Axis Subs: Spies Carried American Money, Elaborate Plans to Impede Progress of our War Effort,” The Washington Post, June 28, 1942.

- ^ “Night of the Nazis: 50 years ago, LIer stumbled upon German saboteurs on the beach,” Newsday, June 13, 1992.

- ^ Johnson, David Alan. Betrayal: the true story of J. Edgar Hoover and the Nazi Saboteurs, (New York: Hippocrene Books, 2007).

- ^ “George John Dasch and the Nazi Saboteurs,” FBI, accessed June 3, 2015, http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/history/famous-cases/nazi-saboteurs.

- ^ “Saboteurs’ Trial to Start in Washington Wednesday,” The Washington Post. July 6, 1942.

- ^ “Night of the Nazis...”

- ^ United States Reports: “Cases Adjudged by the Supreme Court of the United States at July Special Term, 1942,” Library of Congress.

- ^ Johnson, 149.

- ^ “George John Dasch…,” FBI.

- ^ “One Nazi Who Informed On Others Gets Life Term, Second 30 Years; Doomed Six Are Given Scant Notice: Six Nazi Spies Die In Electric Chair,” The Washington Post, August 9, 1942.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ George John Dasch, 8 Men Against America, (New York: R.M. McBride Co., 1959), 17.

- ^ Johnson, 255.

![Small Arms Practice Six OSS recruits watch an instructor shoot a small arm during training at Chopawamsic's Area C. [Source: National Park Service]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2A8CB9F8-1DD8-B71C-070E22100840145DOriginal.jpg?itok=xboGo_08)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)