Witch Hunts in the DC Area - Older Than You Think

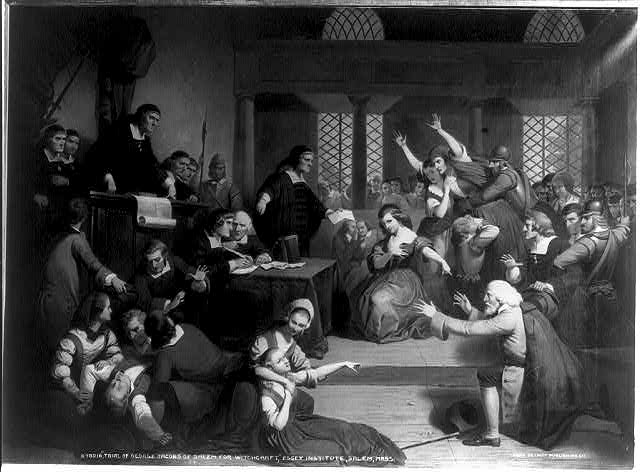

When you think of witch trials, Salem, Massachusetts usually comes to mind, as the site of a rash of accusations and mass hysteria that ended with hundreds accused and twenty people executed for witchcraft in a span of a few weeks. The DMV was never gripped by a panic of Salem’s scope; for one thing, the District was founded in a significantly less witch-paranoid century.[1] However, the area was not quite a stranger to witch trials. In 1635, the Maryland Assembly adopted England’s Witchcraft Act of 1604, declaring witchcraft to be a felony, punishable by death in some instances. Before, witches were the province of the church; now both church and state would punish witches. While this law was seldom used, a few witches were actually put to trial, including Rebecca Fowler, the unfortunate Marylander who was the only person to be executed for witchcraft in the state’s history.[2]

The number of witch trials in Maryland’s history are in the single digits. The few accusations of witchcraft that were brought to court mostly ended in the discrediting of the accuser and lawsuits for defamation.[3] Executions for witchcraft were not common outside of New England (even trials were almost unheard of outside of Massachusetts and Connecticut), but a few occurred elsewhere, including on ships heading to bound for America (in one instance, the captain of a Maryland-bound vessel blamed an old woman on board for causing a storm, and hung her from the mast).[4][5] Most judgements on witchcraft were focused on cracking down on false accusations, which were considered more serious by judges because they could lead to violence (e.g.: Salem).[6] The more southern Chesapeake colonies were less Puritanical than their northern countrymen, and so, as researcher William H. Cooke speculates,”they may have been less inclined to look around every corner for a witch.”[7]

Nevertheless, seven years before the Salem Witch Trials, Rebecca Fowler was accused of witchcraft in Calvert County. Probably in her forties or fifties at the time she was accused, Rebecca lived in the area known as Mount Calvert Hundred, having sailed from England in 1656.[8] She and her husband John met while indentured servants to the same landowner; they had worked their way out of indenture, and her husband had managed to finally purchase some land in 1683. Her accuser was an indentured servant himself, named Francis Sandsbury, who worked on her husband’s plantation, Fowler’s Delight.[9] The details of the incident are unclear, but from what we can infer from court documents, Francis suffered some kind of injury or illness which he blamed on Rebecca. Possibly she cursed at him, or the two had some sort of altercation prior to this injury; either way, he reported Rebecca for witchcraft, and she was seized by the authorities.

The Maryland Provincial Court was the only one in the state allowed to try capital cases, so Rebecca was arrested and taken to trial at the then-state capital of St. Mary’s City, on September 30, 1685.[10] The court brought forward the accusations that she had been “led by the instigation of the Divell” to practice “certaine evil & dyabolicall artes called witchcrafts.”[11] Her indictment declares her to have made Francis’ body “very much the worse, consumed, pined & lamed,” as well as the vague accusation of repeating these offenses on “severall other persons” at “severall other dayes & times.”[11][12] Rebecca pled not guilty to the charges, and requested a jury trial, which she was granted.[13] We have no record of the evidence put forth against her, but the jury must have found it convincing; the twelve jurors found her guilty of the charges against her, and left it up to the court to determine if this meant she met the legal definition of witchcraft. (It’s telling of how few witch trials there were that the court was so unfamiliar with the specifics of the laws on witchcraft that they had to take a recess of a few days to bone up on the particulars.)[14] She was sentenced on October 3, when the justices ordered that she “be hanged by the neck untill she be dead.”[14]

This was an extremely unusual decision. Other trials of similar character occurred, but none of them led to such a harsh sentence. Another woman from Mount Calvert Hundred, Hannah Edwards, tried in 1686 in similar circumstances, was acquitted and set free.[15] (The fact that she probably knew two of the jurors may have had something to do with this, but her case’s result was the general rule rather than the exception.)

So why was Rebecca punished so harshly? One modern scholar, Dr. Rebecca Logan, speculates that the court’s decision may have been linked to a recent scandal that made the court look bad, making them want to appear “tough on crime” and regain their authority in the public eye.[16]Whatever the reason, Rebecca suffered the full punishment of the law for an impossible crime of which she was unquestionably innocent.

The only other time that the Maryland Provincial Court handed down a conviction for witchcraft (John Cowman, convicted in 1674), the putative witch was saved by a last-minute decree of the Maryland Assembly.[17] If Rebecca hoped for a pardon, however, she hoped in vain: the Assembly was out of session during her trial and sentencing.[18] Rebecca Fowler was executed on October 9, 1685, with no chance for appeal.

No other Marylanders shared Rebecca’s fate. The last witch trial in the Chesapeake area was in 1712, when Virtue Violl was acquitted of making Elinor Moore’s tongue “lame and speechless.”[19] Witch trials became much less frequent in 18th-century America, although a handful still occurred sporadically until mid-century; executions for witchcraft in the United States ended with the panic in Salem.[20] In 1736, England repealed the Witchcraft Act; the era of the witch trial was over, but not soon enough to save Rebecca Fowler.[21][22]

More Information

How King James I’s obsession with witchcraft led to the harsh laws under which Rebecca Fowler was prosecuted: http://www.llewellyn.com/journal/article/2186

Information on witchcraft trials in Virginia (there were a few, although none in the DC area): http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Witchcraft_in_Colonial_Virginia

Footnotes

- ^ Although a 2010 Congressional candidate did feel the need to deny she was a witch in a campaign ad.

- ^ Many Marylanders are probably familiar with Moll Dyer, the legendary witch tried in Leonardtown, who fled in the night from the townspeople who burned her cottage, and left marks on a boulder that can supposedly be seen to this day. However, there is no record of a Moll Dyer being tried as a witch, so this tale is unlikely to be historically accurate; there are records of a Mary Dyer immigrating to Maryland in 1677 (Moll was a nickname for Mary), but both Mary and Dyer were fairly common names. (Maryland Hall of Records, Land Books, Liber 15, Folio 438)

- ^ These included a woman named Elizabeth Bennett (no relation), who was accused in October 1665, but escaped without indictment.

- ^ Her name was Elizabeth Richardson, and she was killed in 1658. This led to a trial, in court, prosecuted by John Washington, George Washington’s great-grandfather; the accused shipowner ended up being acquitted because Washington didn’t want to miss his newborn son’s baptism, and so did not appear in court. (Francis Neal Parke, “Witchcraft in Maryland,” Maryland Historical Magazine 31, no. 4 (1936): 274.)

- ^ There were also three executions in Spanish-ruled New Mexico in 1631 (in modern-day Santa Fe).

- ^ William H. Cooke, Witch Trials, Legends, and Lore of Maryland: Dark, Strange, and True Tales. (Undertaker Press, 2012), 30. (Despite the title, this book is actually a well-researched and -sourced historical resource.)

- ^ Ibid., 40.

- ^ Francis Neal Parke, “Witchcraft in Maryland,” Maryland Historical Magazine 31, no. 4 (1936): 291; Rebecca C. Logan, Witches and Poisoners in the Colonial Chesapeake, (Ph.D. Union Institute, 2001), 102.

- ^ Rebecca C. Logan, Witches and Poisoners in the Colonial Chesapeake, (Ph.D. Union Institute, 2001), 112.

- ^ Logan, Witches and Poisoners, 33.

- a, b Parke, “Witchcraft in Maryland,” 283.

- ^ Exactly which other persons, times, or offenses these were is never specified.

- ^ Logan, Witches and Poisoners, 118.

- a, b Parke, “Witchcraft in Maryland,” 284.

- ^ Ibid., 285-6, 291; Logan, Witches and Poisoners, 134.

- ^ Logan, Witches and Poisoners, 123. The scandal, to be more specific, was one in which the temporary regent of Maryland, George Talbot, murdered someone in a dispute while on a ship. The captain took him to trial in Virginia, where the governor refused to return Talbot to Maryland. Talbot later escaped, and the Maryland justices were accused of helping him. After Talbot turned himself in to the Maryland court, the justices waffled until Lord Baltimore returned and managed to secure him a royal pardon. This tarnished the Court’s reputation a great deal, so it is somewhat plausible that they would want to restore it somewhat with a show of decisiveness. (John Fiske, Old Virginia and Her Neighbors, (Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1897), 156-8.)

- ^ Logan, Witches and Poisoners, 38.

- ^ Ibid., 124.

- ^ Parke, “Witchcraft in Maryland,” 288. By this time, skepticism about witch trials was growing, if not about witches themselves. As Thomas Addison said in 1711, “I believe in general that there is and has been such a thing as Witchcraft; but at the same time can give no Credit to any Particular Instance of it.” (289)

- ^ Marc Carlson, “Historical Witches and Witch Trials in North America,” last modified June 13, 2011, http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/witchtrial/na.html.

- ^ Cooke, Witch Trials, Legends, and Lore, 54.

- ^ The last “witch trial” in America happened in 1878, by the way (in Salem, of course), when a woman accused a man of trying to harm her with “mesmeric mental powers” - but that’s an entirely different story.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)