"Will We Let the Ballot Be Taken From Us?": Black Marylanders Fight to Keep the Vote

In 1910, Maryland state senator W. Mitchell Digges was tired of talking about race. For forty years, slavery had been dead in the Old Line State, and Black and White Marylanders had both been able to cast ballots in the state’s elections. And yet, for Digges, everything still seemed to revolve around debating the rights of African Americans. The Charles County native called it “a state of political slavery,” one that spread division and shifted attention from more important issues.

But Digges had a simple answer. All Maryland had to do was ban African Americans from voting and be done with the race question forever. With help from his fellow Democrats, he devised a plan to secure the “elimination of the negro from politics in Maryland” once and for all.[1] But Maryland’s Black community, about 250,000 strong, was not willing to yield their suffrage without a fight. In 1911, they faced off against Digges and his allies to determine the future of democracy in Maryland, and maybe the future of democracy in America at large.

The battle in Maryland was not an isolated struggle. Around the turn of the twentieth century, a wave of disenfranchisement crashed across the southern United States. Starting in the Deep South, White lawmakers from the Democratic Party began stripping away the right of Black Americans to vote. While White “redeemers” had long used violence and intimidation to control the ballot box, they now turned to the more refined power of the law to do the same thing. They passed poll taxes, implemented literacy tests, and rewrote their state constitutions to make it as hard as possible for Black voters to reach the polls.[2]

Though Maryland had fought with the Union during the Civil War, it was still a former slave state. About 20% of its population was African American, and white leaders resented the influence of Black voters. In 1903, the Democratic candidate for governor called the state’s election “‘a contest for the superiority of the white race’’ and said Black voters were “‘dumb driven cattle.’’ He won handily.[3] To begin their disenfranchisement effort, Democrats passed a “trick ballot” law which made the voting process in heavily-Black counties intentionally confusing. They followed it up by placing two constitutional amendments on the ballot to eliminate Black voting rights, one in 1905 and the other in 1909. They both failed to pass, but only barely.[4]

When the state legislature convened in 1910, Sen. Digges believed the third time would be the charm for disenfranchisement. He introduced a package of bills that would, as one of his allies put it, “disenfranchsie the worthless negro.” First, the state would ban all Black people from registering to vote. Then, it would require every voter to re-register before the 1911 general election. Finally, they would submit a constitutional amendment barring Black people from voting forever. With only white people allowed to vote on it in 1911, it would probably pass easily.[5]

The rationale Digges offered was straightforward. In his formulation, it was “not possible for two races as different as the Caucasian and the African to undertake to govern a country jointly.” If there could only be one race in power, Digges saw it as a moral and natural imperative that White people govern. The “law of self-preservation” demanded that they maintain power, no matter what the Constitution may say. To protect white supremacy, Digges lamented that White men had to resort to tactics that “no civilized man ought to be put to the necessity of employing,” a not-so-subtle nod to lynching and violence. His amendment promised to put the issue to rest and spare everyone the hassle.[6]

Though the Fifteenth Amendment clearly stated that states could not discriminate on the basis of race, Democrats argued that it was invalid. Maryland had never ratified it (and in fact did not ratify until 1973). Leading Democrats like Blair Lee of Montgomery County held that this kept the amendment from applying at the state level.[7]

Maryland Republicans, who relied on Black support to compete statewide, were aghast. They did everything they could to fight the proposal, including making the statehouse clerk read lengthy bills aloud to eat up time. But by a one-vote margin, Democrats broke their filibuster and passed the Digges bills.[8] But Governor Austin Lane Crothers, a vocally racist Democrat, decided to veto most of the package. The bills were too blatant, he said, and would provoke immediate blowback from the federal government. Congress might permit racial disenfranchisement in the Deep South, but not just across the District line.

Instead, Crothers called for a vote on just the constitutional amendment. In its final form, the amendment would strip voting rights from any Black voter who did not own $500 in property (about $15,000 today). It would be up to the people of Maryland to decide whether or not to adopt it in the 1911 elections.[9]

As the campaign got underway, things did not look good for supporters of multi-racial democracy. While Democrats were energized, the Baltimore Sun reported that white Republican voters were stuck in “apparent apathy” and were not prepared to fight for their Black party-mates. William Alexander, one of the state’s leading Black activists, lamented that “it looks like the Digges Amendment will be the election law in Maryland.” In his assessment, the passage of the amendment would bring the full force of Jim Crow to bear in the state.[10]

And it wasn’t just about Maryland. Black community leaders saw the election as the latest episode of a national struggle for civil rights that had increasingly turned against them. Another defeat might create an unavoidable snowball of racial restrictions. “Maryland is the border state,” wrote a group of Black citizens in the Baltimore Sun. “If Maryland should pass the disenfranchisement amendment, Delaware would follow suit. Pennsylvania and New Jersey, with their large colored populations, would attempt the experiment. New York would fall in line and there would be no guarantee that New England would not seek an invitation to join the Un-American compact.”[11]

But Maryland’s African American community was ready for a fight. As Margaret Law Callcott wrote, Black Marylanders were known for their uniquely “intense political involvement.” They were better organized and more literate than communities in states farther south, in large part because about half of the state's African American population was free even before the Civil War. Over 40% lived in urban areas like Baltimore, where they were safer from intimidation. And because only one in five Marylanders was Black, the threat of “Negro Domination” held less power as a scare tactic than elsewhere in the South.[12]

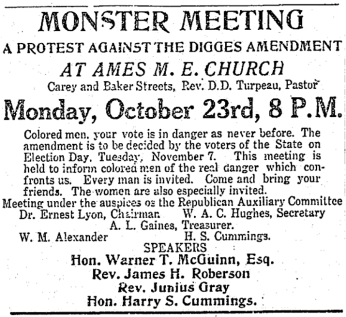

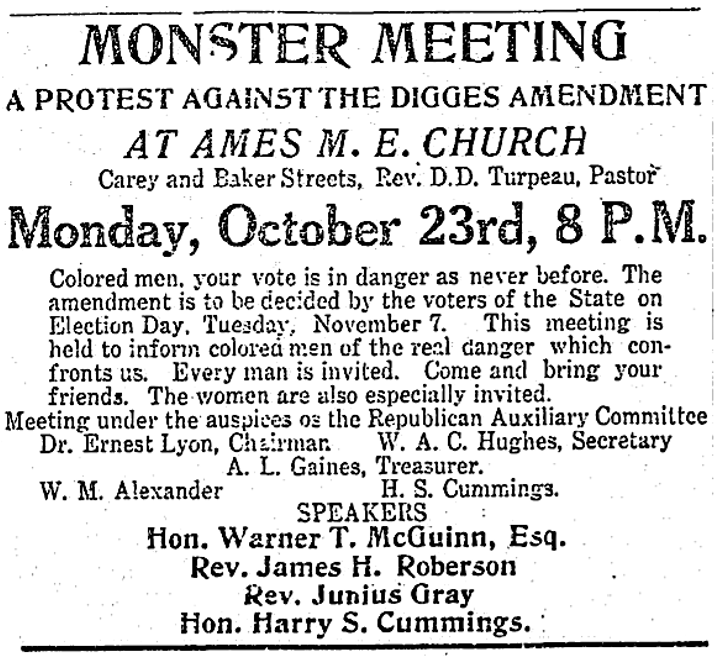

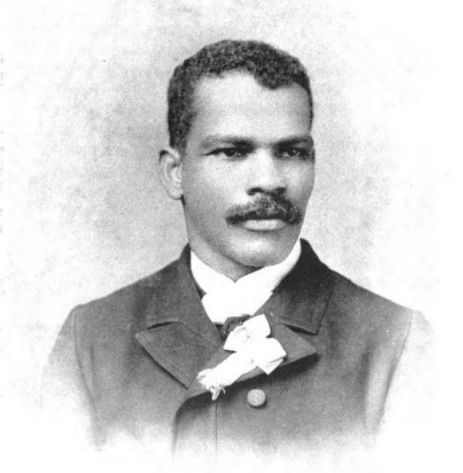

In 1911, every element of the Black society in Maryland got to work. Leading citizens formed an “Auxiliary Committee” to lead the campaign, chaired by former ambassador to Liberia Ernest Lyon. The committee had thousands of copies of the “obnoxious amendment” printed and “scattered broadcast” across the state for all to see.[13] With fundraised cash, they organized night schools where volunteers trained illiterate Black voters how to cast their ballots. Even the New York Sun took notice of the education program, which it called “wonderfully apt.”[14]

The Committee also recruited White voters to fight the amendment. The amendment’s property requirement only applied to African Americans, but if that restriction was deemed unconstitutional, the Committee argued that Democrats leaders might just disenfranchise poor White and Black voters alike. In most southern states, that’s exactly what happened. Bulletins from the Committee argued that “everything which affects the one class of citizens is bound to affect the other class. We are not fighting so much for ourselves as we are fighting for all the people and the progress of the state.” As a result, poor immigrant voters rallied to the cause.[15]

While men were the only ones allowed to vote, Black women played an equal (or even greater) role in helping defend the franchise. The Auxiliary Committee and friendly ministers called on women to use their time and influence to make sure their sons, husbands, fathers, and friends knew when and where to vote. Led by Eliza Cummings, the mother of Baltimore’s first Black city councilman, hundreds of women formed the “Anti-Digges Amendment League.” They knocked on thousands of doors, gave speeches, and helped staff voter training schools.[16]

Their efforts paid off. By the time November 1911 arrived, the issue was as good as settled. “Democrats concede the defeat of the amendment and are making no fight for it,” wrote the Evening Capital and Maryland Gazette. But the anti-amendment forces did not relent. They continued get-out-the-vote efforts on behalf of the Republican ticket, which staunchly opposed the amendment.[17]

On Election Day, the Digges Amendment was crushed at the polls. 65% of voters rejected it. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party which had passed it was driven from power, losing the governor’s mansion for only the second time since the Civil War ended 45 years earlier. As historian Michael Perman wrote, “In no other state was the struggle for constitutional disfranchisement so protracted or so disastrous for its proponents.”[18] Black activists were overjoyed. The Baltimore Afro American quoted William Tyndale, saying with joy that “the universe is full of cogs and wheels and saws and teeth that make for righteousness, and those who get in the way of these are ground to powder.” In their estimate, disenfranchisement was now “down and counted out” in Maryland.[19]

The Afro American was right. No other serious effort to eliminate Black voting rights was ever launched in Maryland. Though smaller discriminatory laws managed to lower African American voter registration from 93% in 1900 to 73% by 1912, that loss was nothing compared to what took place further south.[20] Meanwhile, disenfranchisement efforts halted in their tracks. As Black voters continued to cast ballots north of the Mason-Dixon line, they could thank the hard work of men and women in Maryland for preserving their place in American democracy.

Footnotes

- ^ “A Plea from Mr. Digges,” Baltimore Sun, March 29, 1910, 10.

- ^ Michael Perman, Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001). C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1955).

- ^ Perman, Struggle, 233.

- ^ “Close Fight in Maryland,” The Sun (New York), November 6, 1911, 8. “Disenfranchise White Voters,” New York Times, January 6, 1912, 9. Perman, Struggle, 232. “State Democrats Still Harping on the Negro,” Baltimore Afro American, August 12, 1911, 6. “Don’t Be Fooled,” Baltimore Afro American, September 30, 1911, 4.

- ^ “Barred By One Vote,” Washington Post, April 3, 1910, 9. “Digges Disenfranchisement Plan in Brief,” Baltimore Sun, March 27, 1910, 2. “For Color Line at Polls,” Baltimore Sun, March 23, 1910, 10.

- ^ “Plea,” Baltimore Sun. “Negro Rule by Force,” Baltimore Sun, November 7, 1911, 1.

- ^ “For Color Line,” Baltimore Sun. “State Control An Issue,” Baltimore Sun, March 29, 1910, 10. “Some Baltimore Views,” Baltimore Sun, March 27, 1910, 2.

- ^ “Race Vote Filibuster: Republicans Try to Prevent Disfranchising of Negro,” Wasington Post, March 30, 1910, 5. “Barred,” Washington Post.

- ^ “Will Veto Digges Bill: Governor Says Negro Disfran- chising Is Impractical,” Washington Post, April 9, 1910, 3. “Refuses to Sign Digges Bill,” Washington Post, April 10, 1910, 4.

- ^ “Republican Leaders Will Work Hard to Defeat Amendment,” Baltimore Afro American, July 22, 1911, 6. William Alexander, “Will We Let the Ballot Be Taken From Us,” Baltimore Afro American, July 15, 1911, 4.

- ^ “The Committee's Appeal To The Voters Of Maryland,” Baltimore Afro American, October 21, 1911, 2.

- ^ Stephen Tuck, “Democratization and the Disfranchisement of African Americans in the US South during the Late 19th Century,” Democratization 14, no. 4 (August 2007): 580-602. Margaret Law Callcott, The Negro in Maryland Politics, 1870–1912 (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1969), 155-161, quote on 156.

- ^ “Dr. Earnest Lyon, Former Minister to Liberia, and his Associates in Charge of Auxiliary Headquarters,” Baltimore Afro American, October 21, 1911, 6. “Suffrage League Gets Busy,” Baltimore Afro American, July 15, 1911, 8.

- ^ “Close Fight,” The Sun.

- ^ “Dr. Earnest Lyon,” Baltimore Afro American. Tuck, “Democratization,” 594.

- ^ “Women Will Help to Get Out Voters,” Baltimore Afro American, October 21, 1911, 4. “Negroes in Campaign,” Evening Capital and Maryland Gazette, October 31, 1911, 1. Alexander, “Will We Let the Ballot.”

- ^ “Negroes in Campaign,” Evening Capital and Maryland Gazette.

- ^ Callcott, Negro in Maryland Politics. Perman, Struggle, 230.

- ^ “Three Times and Out,” Baltimore Afro American, November 11, 1911, 4.

- ^ Stats from Callcott, Negro in Maryland Politics, 162.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)