Organ Grinders and Their Monkeys Once Entertained on DC Sidewalks

If you're a Peter Sellers fan, you're probably familiar with this scene in the 1975 film Return of the Pink Panther, in which Inspector Clouseau fails to notice a bank robbery because he is questioning a street accordion player and his chimpanzee companion about whether or not they have the required permit. ("I am a musician and the monkey is a businessman," the accordionist explains. "He doesn't tell me what to play, and I don't tell him what to do with his money.")

You may not realize that there's a grain of truth in the comedy. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, there actually were street musicians who performed with dancing simians in the streets of the nation's capital, and they actually sometimes got into similar beefs with District police. And in one instance, the nation's First Lady reportedly interceded on an organ grinder's behalf.

According to period newspaper accounts, the musicians usually were Italian immigrants, and they usually played what was known as a barrel or street organ. The latter, as described in Douglas Earl Bush's and Richard Kassel's The Organ: An Encyclopedia, was a musical instrument developed in the 1700s in Europe. It was a lot like a player piano, in that a paper cylinder with punches inserted into the box told the organ pipes what notes to play. The musician simply turned the crank on the side, which also operated a bellows that pumped air through the organ's pipes. Bigger street organs needed a cart, but there were also smaller wearable versions. Street organs started out as the musical accompanyment for puppet theaters in Italy. But eventually, itinerant Italian street musicians took them to other parts of Europe and to England, and they eventually started using monkeys who would scamper around and collect change from the audience. (The exception was in France, where contrary to the scenario in Return of the Pink Panther, the organ grinders preferred to work with bichons and other small dogs.)

Sometime in the mid-1800s, immigrant organ grinders started showing up in U.S. cities as well. The first mention of a local man-and-monkey team was in the Oct. 8, 1884 Washington Post. The paper, which in those days sometimes sought to entertain readers with mockery of immigrants, related a tale of an Italian organ grinder "and his red-coated monkey" who walked into the old Deaf and Dumb Asylum at Sixth and M streets, not realizing that the inhabitants would be unable to hear his music. Apparently, though, the residents enjoyed the monkey's antics, because he left "enriched by numerous coppers."

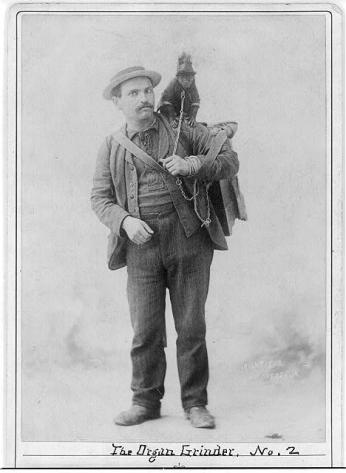

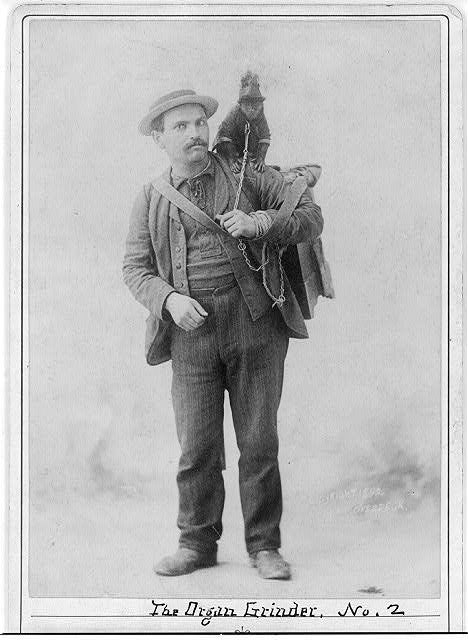

A 1906 Post article described how the man-monkey musical teams operated on downtown streets. The organ grinder would set up on a street corner, wearing his instrument on a strap over his shoulder, and then support its weight with a stick while he plaed. Meanwhile, the monkey, tethered to a leash, would scamper around with a tin cup, collecting change. Audiences were dependable, and "the organ man always knew what the monkey would bring back," the article explained.

Organ grinders and their animals provided entertainment to people who were too poor to afford to go to music halls or purchase phonographs, but better-off Washingtonians often regarded them as a public nuisance. In 1898, a resident named C.A. Snow got police to press cruelty charges an organ grinder for taking his monkey out in cold and damp weather to dance for coins. But others defended the performers. In an 1893 letter to the editor, a District resident named E.C. Palmer lamented that the "doleful grumblings of a few disgrunted dyspeptics can deprive the masses of their chief musical soiree."

It was true, though, that the monkeys and their owners got into scrapes. An 1896 Post article told of a man who was arrested for assaulting an organ grinder and throwing him to the ground on K Street. A 1901 article reported upon an unfortunate eight-year-old boy named Thomas, who ended up in the emergency hospital after being bitten by a monkey who was dancing with an organ grinder at Ninth and E streets. The red-coated simian had been climbing a lamp post "when one of a group of boys seized his tail and gave it a sharp twist." The angry monkey then jumped down from the pole, sank his teeth into the boy's arm, and then proceeded to chew his fingers "with apparent relish" until it was forced to let go. The organ grinder defended his furry partner, complaining that the boys should have left it alone, and then continued his performance with a song entitled "You'll Remember Me."

But gradually the organ grinders began to vanish, in large part because District authorities began making an effort to eliminate panhandling. In April 1930, the Post reported that Walter Proctor, a traveling "hurdy-gurdy man" — another name for organ grinders — had been arrested shortly after arriving in the District. Proctor was hauled before Judge Robert E. Mattingly for soliciting change with the aid of a monkey. Mattingly offered the Italian immigrant a deal. If he agreed not to play his street organ in the District again and immediately left the city on an afternoon train, he wouldn't be prosecuted and put in jail.

"And don't forget your monkey," the judge added. "If you do, we'll have to put him in the zoo." Proctor dutifully obeyed, catching the 2 p.m. train with his animal and heading to Winchester, Va., where he intended to perform at an apple blossom festival.

In 1935, Joe Canzona, a local who might have been the last organ-grinder to work with a monkey in Washington, found himself in a jam when his monkey, Judy, bit a child. According to a 1962 Post article, authorities ordered Canzona to have Judy's teeth removed for public safety, and he reluctantly complied, taking the animal to a dentist in Milwaukee. But Judy was traumatized by the extraction, and by the time they had returned to the District, her fur had begun to fall out and she refused to perform tricks. Canzona sadly then left Washington and returned to Rome with his toothless, balding monkey.

That left but one, monkey-less organ grinder in the District. According to a Dec. 9, 1936 Post article, Pietro "Pete" Battaglioli, who for 20 years had earned a living from passersby who gave him pennies, nickels and dimes to hear songs such as "Dixie" and "Funiculi, Funicula," was stopped by police, who charged him with solicitation of alms. A friend of the organ grinder reportedly wrote a letter about the man's plight and sent it to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who then used her influence on his behalf. District Commissioner Melvin Hazen overruled the police and awarded a license to Pietro. "Organ grinding is no crime," Hazen explained to the newspaper. "If people want to give the man something now and then, I don't think that constitutes solicitation of alms." Battagliola, who complained that the phonograph and the radio were unfair competition, continued working the streets until his death shortly after World War II.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)