George Christian's Shipping Ring

December 13, 1873. The streets of Washington, soupy with mud from the previous day’s rains, began crystallizing with slick patches of ice as the first kiss from winter’s lips touched the city. Despite the oncoming cold, Officer Hawkins remained focused, his suspicions high. Nearby, a horse-drawn wagon and its female occupant continued to sit idle near the circle of 22nd Street. Upon earlier questioning, the young woman claimed she was only waiting for her husband to conduct business in a nearby home. Yet as the minutes ticked past midnight, the hairs on Hawkins’ neck began to stand on end—no honest business took place this late into the night.

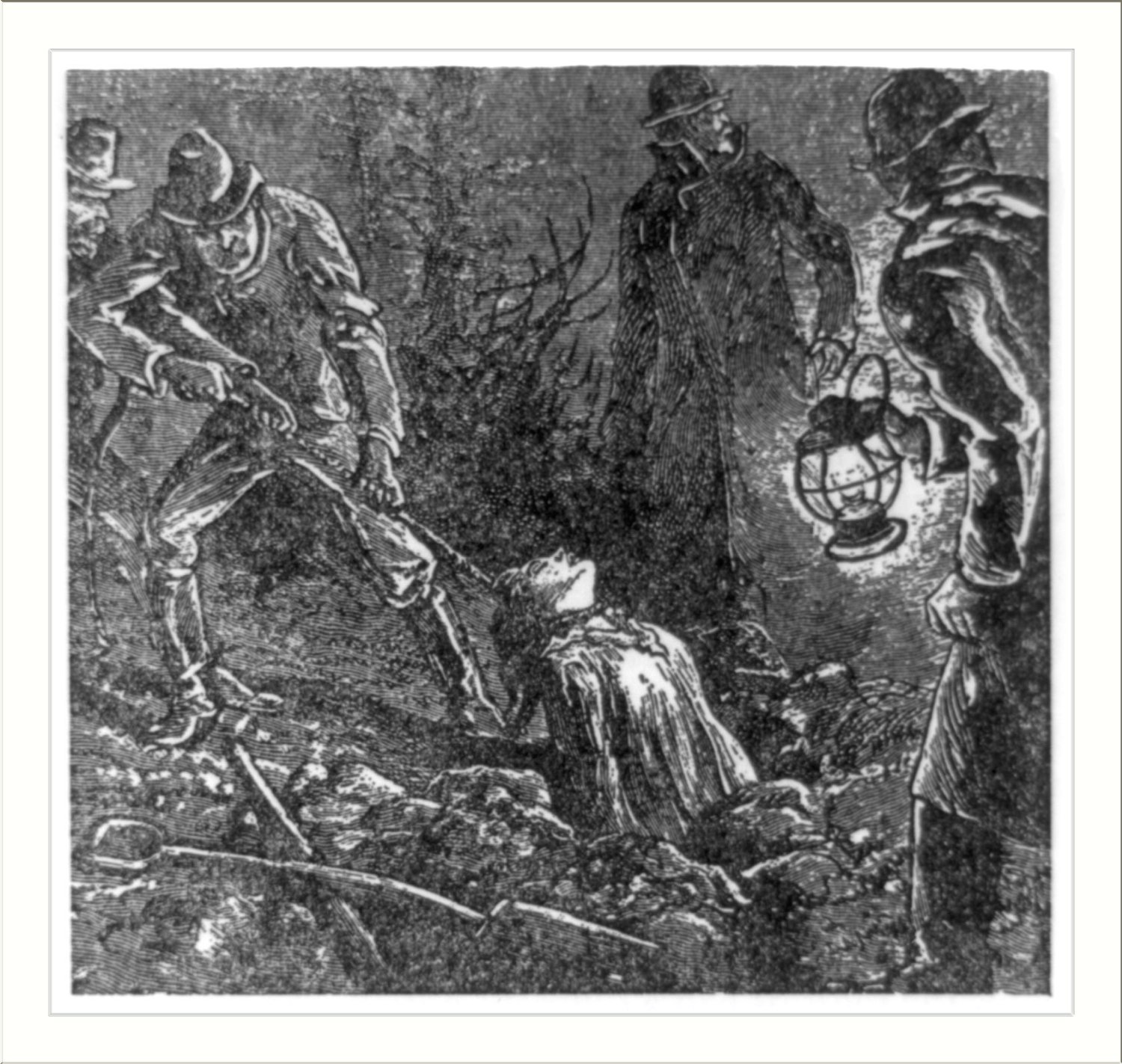

Suddenly two figures approached the woman’s wagon from the east, both carrying shovels. Hawkins smiled despite himself; his suspicions proved correct. As the wagon began moving down New Hampshire Avenue, Hawkins intercepted and arrested its occupants. This group consisted of thieves, Hawkins thought, conducting unseemly business and burying their ill-gotten gains to collect later once the scrutiny of their theft subsided. Only later would he realize the horror of the group’s true business. At nearby Holmead’s burying ground, a passerby discovered a large bag near a fence adjacent to the roadway awaiting retrieval. The bag contained the body of Thomas Fletcher—an African American buried the day before. Hawkins sickened when he heard the news. His suspects were not burying their stolen goods; they were digging up their stolen goods.[1]

In the second part of our Grave Robbing in Washington series, we’ll begin to look at the lives of the individuals who practiced the morbid trade in the cemeteries and potter’s fields of Washington. We’ll begin with the most fascinating professional grave robber documented in Washington, George Christian.

At first glance, Christian fits the mold of the student grave robber. He was born in Ohio and relocated to Washington in the early 1870s to attend Georgetown Medical College. His time there seemed to be a rewarding one. Elected secretary of the junior class at Georgetown in 1872, Christian's popularity and medical training helped him gain access to a clerkship at the Surgeon General’s office.[2]

Christian’s life to this point was uneventful to the vast majority of the District’s populace. This would change on a chilly evening in December 1873. Christian, along with two accomplices —a young woman named Margaret Harrison and an African American named Charles Green — were arrested after attempting to steal the body of Thomas Fletcher from Holmead’s burying ground. Among Christian’s possessions were several letters from medical schools across the country and a detailed journal that exposed Christian as a one-man consortium of body trading across the country.[3]

Christian’s journal is sadly lost to history, but many entries related to the day-to-day operations of a professional grave robber were published in the Jan. 15, 1873 edition of The Evening Star. The entries detailed grave robbing and business practices of Christian and his associates over the course of a full year. Christian employed many people in his grave robbing ring, mostly African American, to help him with collecting bodies. He mentioned that many of these African Americans worked as janitors and day laborers at hospitals and almshouses that Christian frequented during the daylight hours. He also employed women to act as mourners at cemeteries all across the city. They would insert themselves into funeral parties as friends or long-lost family members, marking gravesites with specific flowers which Christian and his associates would use to find their subjects each evening. Most interesting, Christian’s journal showed that he and his cohorts were shipping bodies across the country to medical schools:

Monday, Dec. 1st—Shipped two subjects to Dr. Frothingham today. Sent them in whiskey barrels by express to J.D. Quimby & Co. for him.

Monday, Dec. 8th—Sent two subjects to Virginia this morning, and wrote a letter to Dr. Davis in regard to them.[4]

Shipping bodies across the country was a difficult process during this time, as lack of refrigeration led to bodies rapidly degenerating before reaching their destinations. Any evidence of Christian’s shipping activity occurred in December, allowing the cold temperatures of winter to aid in preservation. Many cadavers were also injected with arsenic in order to prolong their viability. There were also ways to properly ship bodies. Dr. Frothingham, the Michigan medical doctor listed in the entries above, wrote to Christian in April expressing the proper way to pack and ship bodies. Frothingham requested that Christian:

Do not send barrels; they always get the heads knocked in, and excites suspicion if they do not, as the subjects shake about so. The best way to pack is in a tight box three feet by two, or near that dimension, the subject having the legs and thighs flexed and head resting on chest. Sawdust packed about prevent odor and the subject from shaking about in the box.[5]

These precautions showed the lengths that professional grave robbers needed to take to store and ship bodies.[6]

Christian’s work as a body snatcher earned him a $1,000 fine and a year in prison. His fine was waved, but the judge would not lighten Christian’s jail sentence, claiming that his work was not done for the advancement of medical science, but that Christian’s practice “wounded the living…you pursued this as a business, according to your book, and have brought grief to the living.” The fact that Christian used his body snatching for personal profit rather than for the advancement of medical science was the most damning evidence against him, forcing the judge to request a full sentence of jail time for his crimes.[7]

An interesting side note to Christian’s story is that he would be pardoned for his crimes by President Ulysses S. Grant in September 1884 at the behest of “the faculties of the Georgetown and Columbian Medical Schools, the editors of the leading Washington papers and many other citizens of the District of Columbia.”[8] Clearly, Christian’s business was important to a great many in the medical community and to the reporters who covered his crimes.

After his pardon, Christian kept his head down for a few months, but returned to his old game in 1875, setting up a depot on Capitol Hill where he and his associates prepared bodies for shipping along the Baltimore & Ohio railway. On his way to Baltimore, he was spotted by a Washington detective and arrested in September of 1875. Showing skills that he never learned in medical school, he escaped custody in transit from Baltimore to Washington, disappearing from the D.C. area, leaving his wife in Washington unaware of his whereabouts.[9]

Christian’s name comes up in several high-profile grave robbing cases throughout the late nineteenth-century. Many newspapers credited him with masterminding the theft and ransom of the body of Alexander Turney Stewart, a wealthy Irish entrepreneur in New York. Others claimed Christian was one of the culprits who attempted to steal Abraham Lincoln’s body in 1876. It seemed that wherever there was a stolen body, George Christian’s name was sure to pop up. It’s unknown what happened to Christian after his escape from Washington, but it is thought that he returned to his native Ohio. Whether he returned to his grave robbing ways there is a mystery.[10]

George Christian remains one of Washington’s most fascinating professional grave robbers, but he certainly wasn’t the most prolific or the most famous. In our final Grave Robbing in Washington post, we’ll look at a man who claimed to steal over 200 bodies throughout his career; a man known throughout the city as the Resurrectionist King.

Footnotes

- ^ This account was taken from “Arrest of Alleged Body Snatchers,” The Evening Star, December 13th, 1873.

- ^ The Evening Star, January 15th, 1872; January 18th, 1872. Robert S. Pohl, Wicked Capitol Hill: An Unruly History of Behaving Badly, The History Press, 2012, pg. 93-95.

- ^ “Arrest of Alleged Body Snatchers,” The Evening Star, December 13th, 1873.

- ^ “The Resurrection Business,” The Evening Star, December 15th, 1873.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Suzanne M. Shultz, Body Snatching: The Robbing of Graves for the Education of Physicians in Early Nineteenth Century America, McFarland & Co., 1992, pg. 38, 61-68.

- ^ “Christian the Resurrectionist,” The Evening Star, February 9th, 1874. “Dr. Christian, the Body Snatcher,” The Evening Star, June 11th, 1878. ”Adventures of an Expert Body Snatcher,” The Evening Star, June 22nd, 1878.

- ^ The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 25: 1874, http://digital.library.msstate.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/USG_volume/id/24496/rec/26

- ^ The Evening Star, June 11th, 1878; June 22nd, 1878.

- ^ “Grave-Robber Christian,” The New York Times, November 21st, 1878. Wayne Fanebust, The Missing Corpse: Robbing a Gilded Age Tycoon (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005).

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)