America’s First Drag Queen Was a Former Slave from Maryland

On an early spring night in 1888, as the rest of the F Street neighborhood in northwest Washington settles down to sleep, the lights of an unassuming house are burning warmly. From the street, a passerby might see in the windows on the third floor all the signs betraying a lively party: music, chatter, the wide silhouettes of women’s gowns swishing as the attendees dance together.

But what the neighbors do not know is that the party inside is invitation-only, and that there are no women present at all. The party is called a “drag”: a space for queer black men to come together in whatever clothing they wished without fear of judgement or exposure.

The drag participants arrive in carriages, dressed to the nines in “low neck and short sleeve dresses” or “neatly dressed” in jackets. Inside, the room is “heavy with perfume” and a long table is laden with snacks. Refreshments are available: the sideboards are well-stocked with “wine, whisky and beer.”1

At the center of it all is a formerly enslaved black man who has just turned thirty; this “drag” is in honor of his birthday. As such, he is the night’s “queen,” reigning with grace over the festivities in his white silk dress and gold-embroidered slippers.2 His name is William Dorsey Swann, an early queer activist and America’s first drag queen.

Before long, the night will turn chaotic as police arrive and arrest a dozen attendees, including Swann, as others flee the scene, shedding their fine skirts and accessories. But for now, the night is young and the festivities are just beginning.

Much of what is known today about William Dorsey Swann comes from historian and journalist Channing Joseph, who came across newspaper accounts of police raids on Swann’s drag balls while researching his own family tree. He is compiling his research on Swann into an upcoming book called The House of Swann: Where Slaves Became Queens.

Swann was born in 1860 to Mary Jane Younker and Andrew Jackson Swann in Hancock, Maryland. He was the fifth of thirteen children. The family was enslaved to Ann Murray: Mary worked as a housekeeper and Andrew farmed wheat. Joseph writes that growing up, William was close to and admired his mother, who set a strong example as the “matriarch of a large and loving household” even when times were tough.3

Swann and his siblings grew up in Hancock, a busy Potomac River port whose white population was starkly divided between Union and Confederate sympathies. Hancock’s residents struggled during the Civil War as soldiers tramped through the countryside, damaging property and crops. Despite the difficult circumstances, Mary ensured the family celebrated holidays together with singing and dancing—childhood memories that deeply influenced her son William.4 When the war ended, the Swanns were fortunate enough to be able to buy land nearby to start a farm.

But with fifteen mouths to feed, money was tight. Like many other formerly enslaved children, William was not able to go to school but went to work as soon as he was old enough. In the early 1880s, he ventured down from western Maryland to the national capital, looking for a higher-paying job to support his family. He was hired as a janitor in a local college, where his employers described him as “free from vice, industrious, refined in his habits and associations, gentle in his disposition, courteous in his learning” and of a “sensitive nature.” The college also provided an environment to “improve his education,” practicing reading and writing in the classrooms he cleaned.5

It isn’t quite clear when Swann began hosting his “drags” (perhaps as early as 1882), but they were in full swing by 1887. At various houses in the Dupont area, Swann and his acquaintances, many of them also formerly enslaved, traded their uniforms as cooks, waiters, and servants for the sumptuous silks and satins of ball gowns. They would come wearing “corsets, bustles, long hose and slippers” in “the latest fashions.”6 Invitations were circulated secretly to trusted acquaintances by word of mouth at locations like the YMCA. Attendees arrived under the cover of night, stepping out of carriages to mingle with friends, refreshments in hand.

The central event of Swann’s drags was a competition for prizes during a dance: usually a cakewalk, which had been developed by enslaved people on plantations. With its improvisation and use of movement as communication, the cakewalks at Swann’s parties were a precursor to the voguing of today’s ballroom culture. The winners were crowned “queens” of the drag ball. It isn’t certain where that title came from, but Joseph proposes that Swann lifted it from the “Queens of Liberty” he observed in Washington’s Emancipation Day parades: black women perched on flowery floats “personif[ying] African Americans’ newfound freedom.”7

Why the parties were called “drags” is unclear. The word might refer to how long dress hems dragged behind performers.8 It was possibly “a corruption of “grand rag,” an antiquated term for a masquerade ball.”9 What is certain is that William Dorsey Swann was the first to proclaim himself (and others) “queen” of a drag.

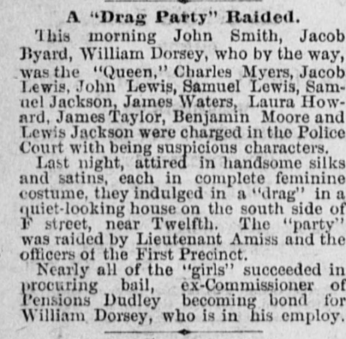

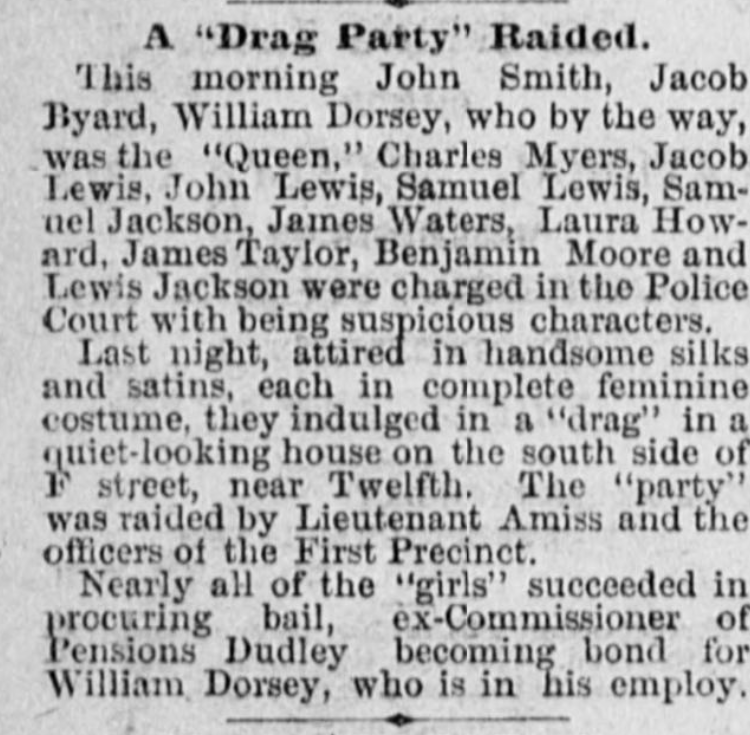

While the parties were a rare chance for queer men (there is no concrete evidence of women attending) to enjoy themselves and foster community, the views of the public were much less benign. Police crashed drags whenever they were tipped off by a neighbor, with the names of those arrested at the parties published, sometimes next to lurid details, in the next morning’s paper. Members of the “House of Swann,” as Joseph called the group, knew that they “faced jail time as well as the possibility of economic and social ruin from being outed.”10

When police arrived at the party in April 1888, Swann ran to block their entry inside with his own body. With “an attitude of royal defiance,” he reportedly snapped at the police, “You is no gentlemen,” as they tried to force their way past him.11 In the ensuing struggle, Swann’s gown was torn to shreds and he was arrested along with a dozen others. But by resisting (and becoming the first documented example of violent queer resistance in America), he was able to buy time for other attendees to escape: out of windows, through a skylight, onto the sloping roofs of the neighbors’ houses. A few leapt out of the third story window, breaking through a skylight below with a “rattling and crashing” of glass.12

The attendees who were not able to escape faced humiliating judgement both by the law and their neighbors. As Swann and others were marched towards the police station, a reporter noted that “men who had caught on to the situation followed after and gibed the prisoners, especially those in women’s clothes.”13 Most of the times Swann and other drag participants were arrested, they were charged with vague offences like “vagrancy” or being “suspicious characters.”14 They were often given thirty days in jail or an option to post bond.

Drag balls—and their participants—were deemed morally dangerous because they challenged norms of gender and sexuality in nineteenth-century America. Queer identities at the time, when they were discussed, were often treated as pathological oddities, a type of psychological aberration. Words like lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and other language of self-identification were still on the verge of developing. Queer individuals might have been lumped under other terms like “erotopathy,” an outdated term meaning “an abnormality of sexual desire.”15 Swann would have had to look no further than medical journals of the day to see how doctors discussed the very drag parties that were going on in Washington. In medical journals, Washington’s drag balls were described as “orgie[s] of lascivious debauchery” and “sable performance[s] of sexual perversion.”16

In reality, Swann’s parties likely offered just the opposite. At a time when the best opportunity to meet other gay or genderqueer people was by cruising for sexual partners in Lafayette Square, Joseph notes that an invitation to a drag ball was an “opportunity to transgress nineteenth-century social norms in a supportive and primarily nonsexual environment” and to “deepen social bonds without the expectation of sex, the need to prostitute themselves, or the pressure to perform for an audience of leering outsiders.”17 It was also one of the few places in which queer life was not segregated: while most of the invitees were black (a fact which made raids on the parties and ensuing arrests “even more sensationalized”), drag parties were mixed-race in attendance.18 To attend a Swann drag, all one needed was their dancing feet.

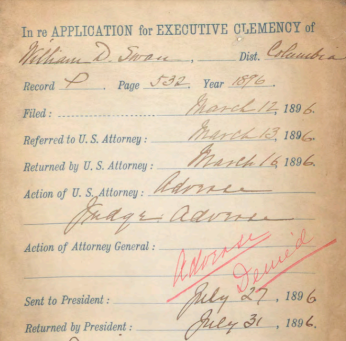

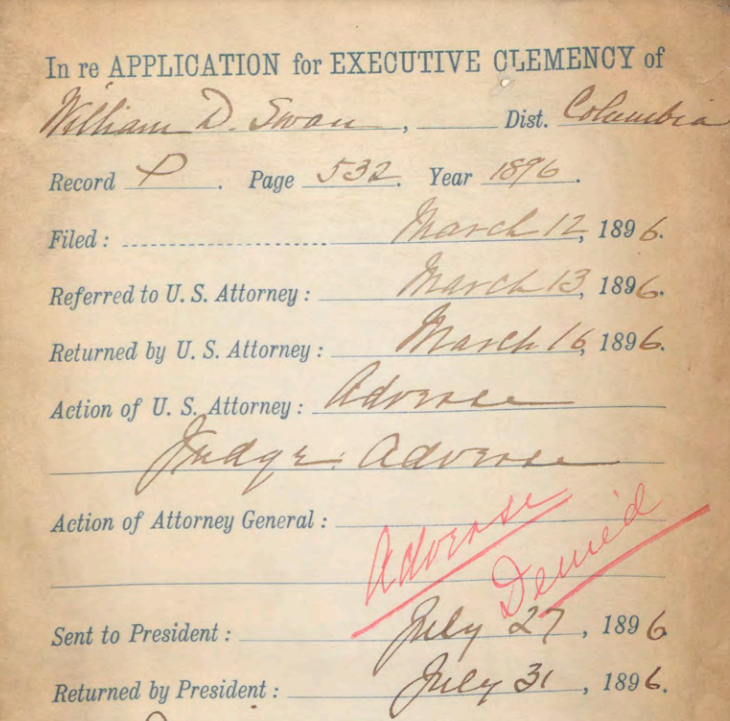

In 1896, though, the party came crashing down a bit harder than usual. While white and black partygoers were enjoying themselves at Swann’s house on L Street, police raided the building, arresting Swann. It was not his first arrest, but the consequences this time looked to be more serious. During the trial, the irate judge called Swann’s house a “hell of iniquity.” In less than twenty-four hours, William Dorsey Swann found himself convicted of “keeping a disorderly house” (a euphemism for a brothel) and sentenced to ten months in prison—without a bond to get him out this time.

Three months into his sentence, from his cell Swann wrote a petition for a presidential pardon. In doing so, he became the first person “to use the legal and political system to fight for the right of the queer community to gather in America.”19 He argued for his release on three points: that he had “always been a hard working and industrious man,” the court had punished him with “unusual severity,” and he would “hereafter live a proper and law abiding life” after release.20

There were also the matter of his health. Several of Swann’s friends had already called the prison office to voice their concerns over his well-being even as prison physicians maintained that Swann was in “very good health.” However, in July the doctor found that Swann had a “disease of the heart.” Serving his full sentence, he conceded, “will endanger his life and health.”21

The file sent to the White House also included notes from legal officials who harshly criticized the deviation from social norms inherent in Swann’s drags. Attorney A.A. Birney wrote that Swann was convicted of “an offence so disgusting that it is unnamed” and argued that Swann “should have been sentenced had it been possible, to so long a period in the penitentiary that his presence in the community could never again pollute it.” The judge who oversaw Swann’s trial “thoroughly endors[ed]” Birney’s opinion.22

President Cleveland ultimately denied the petition when it landed on his desk in July. In a short memo on Executive Mansion stationary, he wrote that the “representations” of the petition did not outweigh the “character of his offense.”23 Swann finished his sentence in September, 1896.

When he was released from prison, Swann was beginning to think of stepping away from his reign as queen of drag balls. Years of notoriety in Washington’s newspapers—and becoming synonymous with the city’s nascent drag scene—hampered his ability to find work. By 1900, he had returned to his family in Hancock, where he lived until 1925. When he died, city officials set his house on fire, destroying any documents or artefacts that might have been inside.24

In the capital, Swann’s legacy nonetheless lived on. His brother Daniel (who was arrested at more than one of William’s drag balls), a tailor, continued to provide women’s clothing for Washington’s drag scene until 1954. The “House of Swann” might credibly be called the forerunner of all modern ballroom culture, which follows the same basic structure William developed: “chosen families led by “queens” and “mothers” who officiate at beauty and dance competitions.”25

In July of 2022, neighbors in the Dupont area began advocating that Swann Street NW be officially rededicated to William Dorsey Swann (it had been named for Maryland congressman Thomas Swann). The DC council approved the bill in July 2023, promising to install a commemorative sign to mark Swann’s “historic contributions” to the Washington—and American—queer community.26

Footnotes

- 1

National Republican. (Washington City (D.C.)), 13 April 1888. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 2

National Republican. (Washington City (D.C.)), 13 April 1888. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 3

Joseph, Channing. “William Dorsey Swann - Oxford African American Studies Center.” African American National Biography, 2021.

- 4

Joseph, Channing. “William Dorsey Swann - Oxford African American Studies Center.” African American National Biography, 2021.

- 5

J-202, William D. Swan, 1882, NAID 165128485. Pardon Case Files Series, Record Group 204, National Archives, Washington D.C.

- 6

The Washington critic. (Washington, DC), Jan. 15 1887.

- 7

Joseph, Channing. “William Dorsey Swann - Oxford African American Studies Center.” African American National Biography, 2021.

- 8

Shane, Cari. “The First Self-Proclaimed Drag Queen Was a Formerly Enslaved Man.” Smithsonian Magazine, June 9, 2023.

- 9

Joseph, Channing. “William Dorsey Swann - Oxford African American Studies Center.” African American National Biography, 2021.

- 10

Joseph, Channing. “Channing Joseph: Historical Research and Discoveries.” Accessed May 20, 2024.

- 11

National Republican. (Washington City (D.C.)), 13 April 1888. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 12

Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 13 April 1888. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 13

National Republican. (Washington City (D.C.)), 13 April 1888. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 14

Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 13 April 1888. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 15

Merriam Webster Medical Dictionary. “Definition of Erotopathy.” Merriam-Webster Medical. Accessed May 20, 2024.

- 16 Hughes, Charles Hamilton. “Postscript to Paper on ‘Erotopathia’—An Organization of Colored Erotopaths.” Alienist and Neurologist 14, no. 4. (October 1893): 731–32.

- 17

Joseph, Channing. “Channing Joseph: Historical Research and Discoveries.” Accessed May 20, 2024.

- 18

Shane, Cari. “The First Self-Proclaimed Drag Queen Was a Formerly Enslaved Man.” Smithsonian Magazine, June 9, 2023.

- 19

American Masters PBS. “William Dorsey Swann: The First ‘Queen of Drag.’” Video. YouTube, October 6, 2021.

- 20 P-532, William D. Swan, 1896, NAID 165128484. Pardon Case Files Series, Record Group 204, National Archives, Washington D.C.

- 21 P-532, William D. Swan, 1896, NAID 165128484. Pardon Case Files Series, Record Group 204, National Archives, Washington D.C.

- 22 P-532, William D. Swan, 1896, NAID 165128484. Pardon Case Files Series, Record Group 204, National Archives, Washington D.C.

- 23 P-532, William D. Swan, 1896, NAID 165128484. Pardon Case Files Series, Record Group 204, National Archives, Washington D.C.

- 24

Joseph, Channing. “William Dorsey Swann - Oxford African American Studies Center.” African American National Biography, 2021.

- 25

Joseph, Channing. “William Dorsey Swann - Oxford African American Studies Center.” African American National Biography, 2021.

- 26

Grablick, Colleen. “Swann Street Re-Dedicated For First Known Drag Queen.” WAMU 88.5 - American University Radio, July 14, 2022.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)