Benjamin Banneker's Capital Contributions

Benjamin Banneker was already a practiced mathematician and astronomer when he was approached in February 1791 by his friend Andrew Ellicott to survey the land staked out for the new United States capital. A free black who grew up in Maryland as a farmer, Banneker was more than a laborer. Though his formal education ended at an early age, he continued to study science and physics and would later write a series of best-selling almanacs. He designed and built a striking clock at age 22 that kept perfect time for forty years until it was destroyed in a fire.[1]

Banneker’s principal role in surveying the new capital was to make astronomical observations for which the survey’s starting point could be determined. He also used his calculations to establish the boundary points for the district. Banneker was well suited for this role, having already accurately predicted solar and lunar eclipses, sunrises, and sunsets. But his contributions to the creation of the nation’s capital would grow beyond what anyone anticipated.

When the United States officially adopted the Constitution in 1789, there was as much debate about the location and shape of the new federal capital as there was about the other affairs of the new nation. The argument over its location, whether it be Boston or Philadelphia or New York, was so vehement that some feared it would shatter the unity of the young republic before it got off the ground.

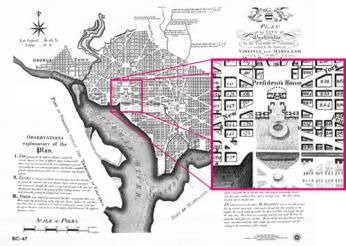

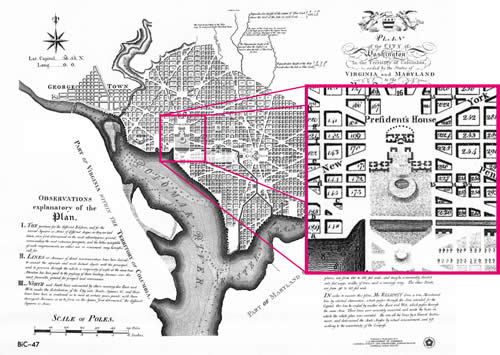

Even before the location was settled for a new federal capital called for in the Constitution, Pierre Charles L’Enfant wrote George Washington with a request to be commissioned to design the federal city. He was granted his wish when Congress passed the Residence Act of 1790, which set the permanent site for the capital on the Potomac River.[2]

L’Enfant, who served under Washington during the Revolution and was a successful civil engineer after the war, developed a grand design for the capital. “The entire city was built around the idea that every citizen was equally important,” wrote L’Enfant biographer Scott Berg. “The Mall was designed as open to all comers.”[3]

L’Enfant’s plans were well received, but he proved to be extremely difficult to work with, arguing incessantly with the commissioners in charge of the capital project. He frequently stepped beyond his mandate in budgetary and design issues, and Washington begrudgingly relieved him in 1792. When L’Enfant left the project, he took all the designs with him, leaving the project in disarray.

Unsure of how to proceed, Ellicott and the other planners feared they might have to start from scratch. According to writer Gaius Chamberlain, “Banneker surprised them when he asserted that he could reproduce the plans from memory and in two days did exactly as he had promised.”[4]

There has been much controversy over the years about whether such an event actually happened. Some historians claim that many of the facts about Banneker’s life were embellished or mythologized, leaving the fact that he was able to reimagine L’Enfant’s plans in dispute. Others have theorized that it was Andrew Ellicott’s brother Benjamin who aided in redrawing the plans from memory, theorizing that he was confused with Banneker because they shared the same first name.

In the final analysis, it cannot be denied that Banneker was a confirmed member of the team that designed the federal capital which would soon become known as Washington, D.C. In being a part of that team, Banneker, a free black man in a nation that was still practicing slavery, used his intellect and skill to disprove the theory that blacks were an inferior race. The extent of his contributions to the design and building of the U.S. capital may be disputed in some circles, but that Banneker played an important part in that grand project is a matter of public record.

Footnotes

- ^ Africans in America, Benjamin Banneker, PBS, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2p84.html

- ^ Officially titled “An Act for Establishing the Temporary and Permanent Seat of the Government of the United States,” the Residence Act also set Philadelphia as the interim capital for ten years until the permanent transfer to the federal city on the Potomac River. https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/Residence.html

- ^ Quoted in Kenneth R. Fletcher, “A Brief History of Pierre L’Enfant and Washington, D.C.,” Smithsonian Magazine, April 30, 2008. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/a-brief-history-of-pierre-le…

- ^ Gaius Chamberlain, “Benjamin Banneker,” The Black Inventor Online Museum, March 11, 2012. http://blackinventor.com/benjamin-banneker/

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)