Before the Bonus Marchers There was Coxey's Army

You might be familiar with the story of the Bonus Marchers of 1932, the large group of World War I veterans who gathered from around the country in Washington, D.C., demanding their long-promised benefits. For many veterans, the bonus money for military service was the difference between keeping a roof over their families’ heads or keeping the bank from repossessing their property. But this was not the first time disgruntled citizens descended on Washington seeking economic redress.

In 1893, after years of sustained economic growth in the United States, the bottom fell out of the credit markets. The failures of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad on February 26, the National Cordage Company on May 5, and the Erie Railroad on July 25, caused concern about the solvency of other firms and created a run on banks and currency.[1] Unemployment reached record levels and many families became destitute.

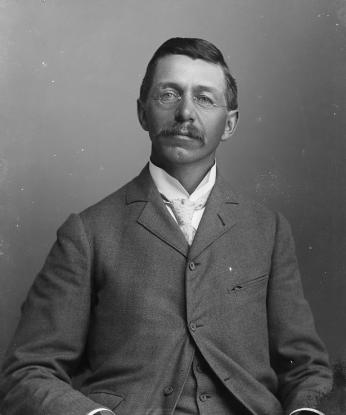

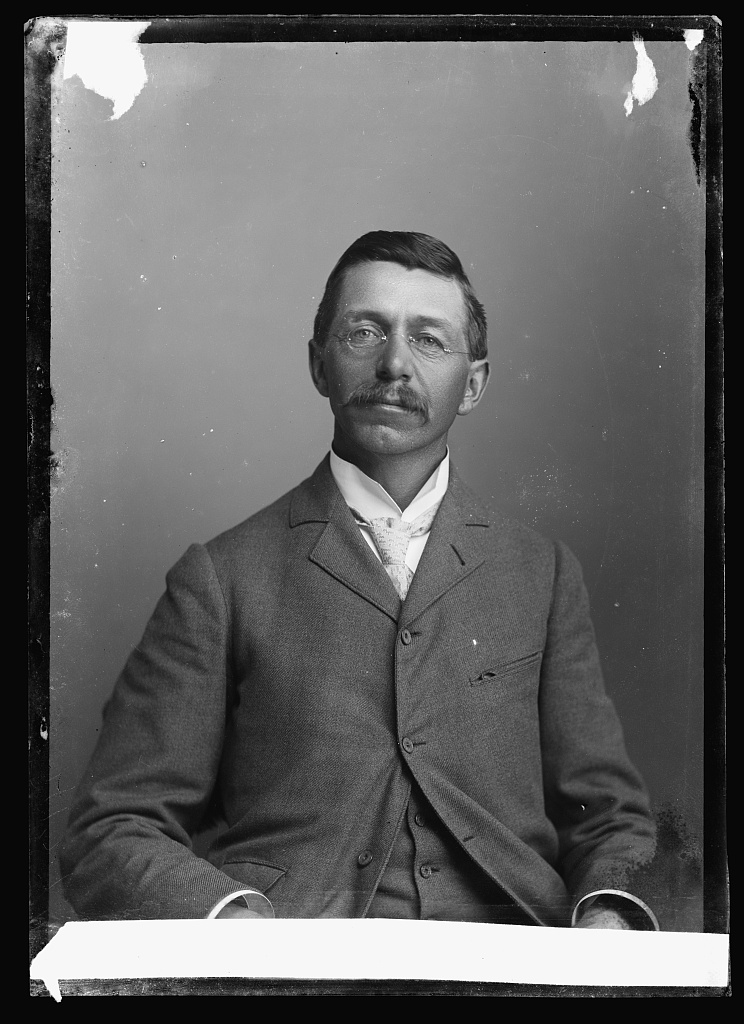

In early 1894, Ohio businessman Jacob Coxey devised a solution by proposing a plan through which the government would hire men to work on public infrastructure projects. Coxey’s Good Roads Bill was far ahead of its time, preceding Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal by decades.

Coxey and his eccentric colleague Carl Browne, who fancied himself the reincarnation of Jesus Christ, put together a collection of unemployed men and women to march to Washington to present their plan. They left Massillon, Ohio on March 25, arriving in Washington, D.C. at the end of April. Along the way, they were joined by dozens of similarly affected men and women eager to find a solution to their economic plight.

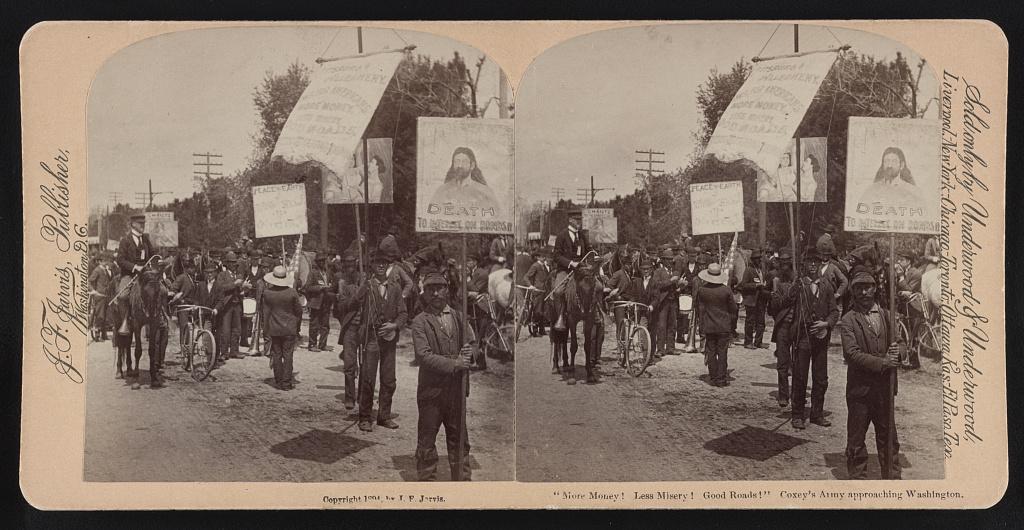

Coxey and Browne called their group the Commonweal of Christ, but the press and the public referred to them as Coxey’s Army. The group earned the sympathies of many who felt the federal government wasn’t doing enough to address peoples’ problems. The government itself and the wealthy, however, believed that Coxey’s Army and similar gatherings around the country were early signs that a class war that was brewing.

Coxey’s Army marched on the Capitol on May 1, and the authorities were ready. “While the Coxeyites were marching, the Metropolitan Police were drilling, and Army and Marine units were on alert for the occasion,” writes Benjamin Alexander. “Moreover, officials in the capital had made clear that they had full intention of enforcing the 1882 Capitol Grounds Act prohibiting political processions and the display of political flags and banners on Capitol property.”[2]

The First Amendment guarantees the right of the people to petition the government for a redress of grievances, but according to the laws of the time, they could do so only if they kept off the grass. When Coxey, Browne, and company approached the Capitol to read the Good Roads Bill, they were swarmed by the police. People were clubbed, and Coxey was arrested and sentenced to 20 days in jail.

The Good Roads Bill never came to be, but Coxey became a hero of the Progressive movement. He was invited back to Washington on May 1, 1944 to read the petition he was never allowed to fifty years earlier, and he lived to see the proof that his ideas could be put to use for the public good.[3]

Footnotes

- ^ See Mark Carlson, “Causes of Bank Suspensions in the Panic of 1893” for more information on the causes and reactions to the bank panic. http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2002/200211/200211pap.pdf

- ^ Benjamin Alexander, “In 1984, Coxey’s Army knew how to get the attention of Congress (without a gyrocopter).” JHU Press Blog, Johns Hopkins University Press, May 1, 2015. http://jhupressblog.com/2015/05/01/in-1894-coxeys-army-knew-how-to-get-…

- ^ See Jon Grinspan, “How a Ragtag Band of Reformers Organized the First Protest March on Washington, D.C.,” Smithsonian.com, May 1, 2014. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-ragtag-band-r…

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)