Minnie Keyes: Savior or Slumlord?

In 1933, eleven words made Minnie Keyes a wealthy woman. They were scrawled on a blank telegram slip, tied to a pencil with an elastic band, and stuffed under a mattress. “Minnie Keyes: You have been good to me. All is yours.” These sentences were the final will and testament of Leonard A. Hamilton, who had lived as a boarder at Keyes’ home for 30 years. Once a court accepted the scrap as legitimate, Keyes inherited Hamilton’s $100,000 estate, about $2.1 million in today’s money. Most of its value lay in real estate: dozens of homes scattered across Washington.[1]

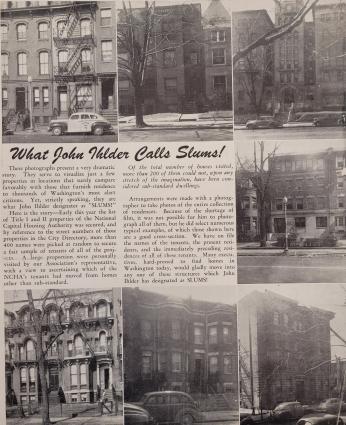

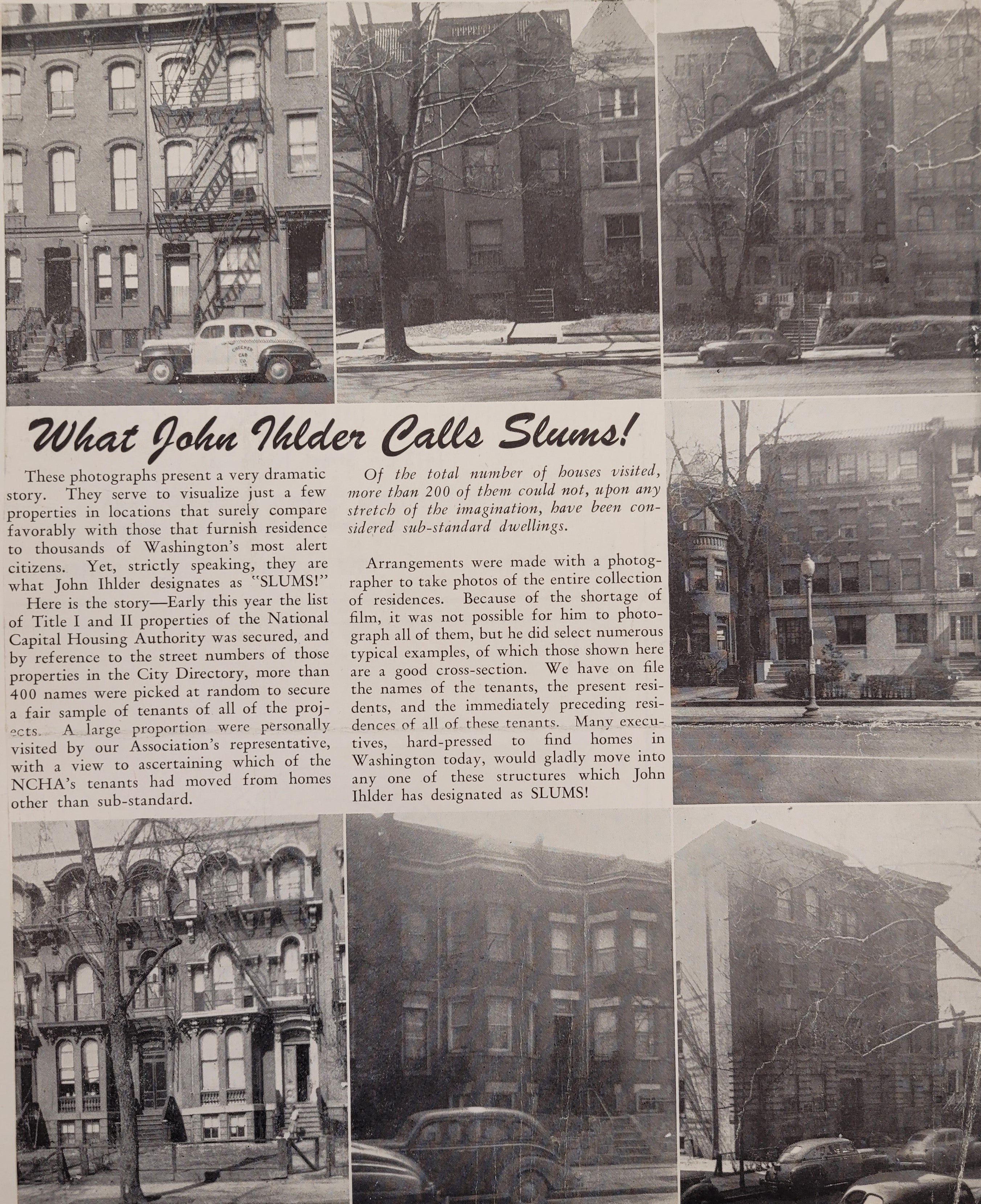

The properties Minnie Keyes came to own, however, were not the city’s best. They were almost all worn-down, overcrowded, and in desperate need of repair. The properties were concentrated in Southwest, and almost everyone who lived in them was Black. To most observers, they were “slums.” The government wanted them gone. But Keyes, a White D.C. native, was not going to let go without a fight. For the next twenty years, she fought federal and local officials over her houses- and over the future of housing in the District of Columbia.

The contested terrain of housing policy that Keyes barreled into after inheriting Hamilton’s properties was decades in the making. Since the Civil War, the poorer sections of the District had been notoriously overcrowded. The city became infamous for its congested alleys, where throngs of impoverished, predominately Black families lived without clean water or adequate shelter. Reformers like First Lady Ellen Wilson wanted to change this, but they never managed to affect widespread redevelopment.[2]

But in the 1930s, the long-awaited transformation of Washington’s “slums” finally got under way. With New Deal money from the federal government, officials set their sights on building quality public housing for low-income people. In 1934 Congress created the Alley Dwelling Authority (ADA) and gave it power to develop better properties in the place of decrepit homes. The ADA was led by local activist John Ihlder. He envisioned a grand redevelopment of the city’s poorest areas, destroying squalid alleys and replacing them with modern public housing. In the process, Ihlder hoped to transform the poor population too. Looking at poor Black communities with a mix of sympathy and condescension, he hoped that “with dwellings of a different type, the character of the people will be altered” as well.

Not everyone shared Ihlder’s vision, though. Most city planners had no interest in making new developments open to the Black people who had once lived on their sites. Where Ihlder saw a chance for uplift, they eyed profit and commercial growth. The ADA even held meetings at segregated venues where their own Black staff were not permitted to attend. As a result, “few black Washingtonians had faith that white housing reformers had their best interests at heart,” according to Chris Asch and Derek Musgrove. They worried that government officials would claim their homes and then fail to replace them with affordable, non-segregated living options. The reality of the wrecking ball always seemed to overshadow the promise of better things to come.[3]

This was the perspective that Minnie Keyes adopted when she first came into conflict with government housing reformers. In 1935, the Public Works Administration, in cooperation with the ADA, revealed big plans to redevelop an area of Southwest Washington near the Army War College, close to where Nationals Park now stands. They wanted to clear out the “sprawling Negro slums” and spend $3 million on new, low-cost housing. Fifteen of Keyes’ inherited properties stood on the proposed site: 121 to 141 P Street, 1256 to 1261 Half Street, and 9 and 10 Pierce Court SW. The Washington Post called the P Street houses “a low row of dingy clapboarded dwellings joined together.” But they were in the middle of the proposed 17 acre development, and nothing could proceed without tearing them and the others down.[4]

However, Keyes was not willing to let them go. The government offered her just $3,000 for the houses, not much considering that they generated $1,000 a year in rent. And it was not just about the money. Speaking to the Post and Evening Star, Keyes criticized the whole system of redevelopment in D.C. “This slum clearance is only a money-making scheme,” she said. “They don’t care anything for the colored people and they don’t care about me.”

In contrast to common depictions of Southwest as a crime-ridden hellscape, Keyes called it “nice and quiet,” a community where White and Black Washingtonians had lived contently for generations. In her view, redevelopment threatened to destroy this status quo. While her houses rented for $10 to $12 a month (about $200/month in 2021 dollars), Keyes warned that new units could cost two times that with only marginal gains in quality. And in segregated Washington, there was no guarantee that the mostly-Black tenants who occupied her houses would even be allowed to rent what replaced them.[5]

Keyes’ arguments were not based on hypotheticals. They were already playing out in other portions of the city. In Foggy Bottom, the ADA levelled the homes of poor Black residents, but tried to replace them with white-only housing. Only concertered activism secured access for the people who had once lived there. And in the Fort Reno neighborhood of Tenleytown, city and federal officials used eminent domain and building condemnations to expel Black homeowners to make way for new houses that were only available to White buyers. It was not unreasonable to expect that the same might happen in Southwest.[6]

To avoid that fate, Keyes rallied other local property owners. They sued the Public Works Administration, arguing that the agency had no right to claim their houses because “slum clearance” was not a public good. They were bolstered by a recent case from Louisville where a court deemed that the federal government could not claim land just to build low-cost housing. Federal lawyers insisted that they had the legal authority to act, but the District Supreme Court disagreed. They ruled that condemning land to build new residences was not a legitimate use of power. Keyes could keep her houses.[7]

But the housing issue did not fade away. In 1937 Congress passed the Wagner–Steagall Act, which expanded the country’s public housing programs. The law enlarged the power of the Alley Dwelling Authority, and recharged the enthusiasm of activists for low-cost housing. But there was a catch. To appease southern congressmen and the real estate lobby, the law created an “equal elimination” principle. For every new unit of public housing created, one unit of existing housing had to be destroyed. As a result, there would be no progress in D.C. without demolition to go with it.[8]

In 1941, the ADA put this new principle to work in Navy Yard. They planned to build the Carrollsburg Dwelling project, offering low-rent housing to Black families, but they needed to clear land and units to make it happen. Among those houses slated for demolition was another Keyes property: 407 L Street SE. This time, officials knew what to expect from Keyes, so they moved fast. Before Minnie could even file an injunction, the building had already been partly demolished. “I warned them not to touch my property,” she fumed to the Star, “but they began tearing it down anyway.”

In court, Keyes argued that her property was not in an alley and had not been deemed unsafe, so the ADA had no right to take it. But this time, the courts disagreed. The Court of Appeals ruled that Congress had all the powers of a state government when acting within Washington, and if they wanted to use eminent domain to claim land for public housing, they could. Keyes v. U.S. was the first case to confirm this federal power, and over the next 10 years, John Ihlder and the ADA ran with it, building low-rent projects across the city.[9]

But Minnie Keyes never quit fighting. Neither did District officials. In 1945 they condemned her houses on P Street and other properties in Southwest. Keyes sued again, filed extensions and challenges, and kept the struggle going. ”[10] But the years of appeals highlighted just how rundown Keyes’ houses were. Though Keyes claimed that “I keep my rents down and I keep the properties up,” almost every observer said the opposite. During one court fight, Judge Matthew McGuire was invited to tour the houses, and he declared that the D.C. government would have been “derelict in its duties” to not condemn them. In an editorial, the Washington Post called them “wretched quarters” that were “not fit for human habitation.[11]

News coverage of the case never bothered to ask Keyes’ tenants what they thought of the conditions; for instance, whether the seeming squalor they lived in was worth the low cost and stability. But almost everyone in a position to judge the properties agreed that these homes were not fit to stand in a modern American city. Keyes may have positioned her properties against the specter of racist displacement, but the status quo she fought for (and profited from) seemed even more destructive.

Ultimately, Minnie Keyes never had to watch her houses meet the wrecking ball. She died in 1957 at age 67.[12] Six months later, D.C. officials finally tore down the P Street properties that stood at the center of her disputes. In an article on the demolition, the Post wrote that “the walls of the most publicized condemned houses in the District are finally tumbling down.” A relieved member of the District Board of Condemnation of Insanitary Buildings reflected that it was the “most stubborn case we’ve encountered.”[13]

An era of housing in Washington died alongside Minnie Keyes and her properties. The ramshackle wooden homes that once defined whole sections of the city became a thing of the past. But many of the dynamics that shaped her fight persist in the city’s current period of rapid growth. Homeowners, activists, and officials still debate whether the promise of progress justifies the risks of displacement and disruption. And today, just like the 1930s and 40s, separating the good from the bad remains an almost impossible task.

Footnotes

- ^ “Brief Will: "All Is Yours" Is Penned to Dispose of $11,000 D.C. Estate,” Washington Post, March 19, 1933, 9. “All is Yours,” Washington Post, March 25, 1933, 2. “Briefest of Wills Leaves ‘All’ to One ‘Good to Me,’” Evening Star, March 18, 1933, A14. “Eleven-World Scribbled Will Giving $90,000 Estate Upheld,” Evening Star, December 12, 1933, A1.

- ^ Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove, Chocolate City: A History Of Race And Democracy In The Nation's Capital, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 179-180, 200-206.

- ^ Ibid, 252-260.

- ^ “$3,000,000 Slum Clearance Is Imperiled by D.C. Woman,” Washington Post, July 18, 1935, 1. “Slum Clearance Plan Hits Snag,” Evening Star, July 18, 1935, A4. “Air View of D.C. Slum Clearance Area,” Evening Star, August 4, 1935, A14.

- ^ “$3,000,000 Slum Clearance,” Washington Post. “Slum Clearance Plan,” Evening Star.

- ^ Asch and Musgrove, Chocolate City, 254-258.

- ^ “U.S. Has Power To Ban Slums, Says Counsel,” Washington Post, July 21, 1935, 10. “Slum Clearance Suit Withdrawn,” Evening Star, July 25, 1935, A1. “Owner Renews Fight,” Evening Star.

- ^ Gail Radford, Modern Housing for America: Policy Struggles in the New Deal Era, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 189-191.

- ^ “Owner Renews Fight,” Evening Star. “Slum Clearance in D.C. Upheld by Court,” Evening Star, March 10, 1941, A1, A4. “Appeals Court Upholds ADA Housing Plan,” Washington Post, Mar 11, 1941, 1.

- ^ “Woman Fined for Renting Condemned Building,” Evening Star, June 27, 1945, A3. “Woman Owner Fined $500 for Renting Unsafe Housing,” Evening Star, August 11, 1945, B3. “Owner of 11 Houses Sues to Void Condemnation,” Evening Star, March 23, 1946, B4. “D.C. Wins New Round in P Street Houses Condemnation Fight,” Evening Star, April 8, 1948, B1. “D.C. is Upheld in Condemning Slum Buildings,” Evening Star, December 16, 1949, A1. “Highest Court Refuses to Rule on District Condemnation Claim,” Evening Star, April 4, 1950, A4. “Court Supports Ruling Southwest Houses Are 'Unfit,’” Washington Post, April 8, 1948, B1. “3 Slum Property Cases Delayed,” Washington Post, June 28, 1955, 22. “Judge Delays Condemnation Case Penalty,” Washington Post, September 30, 1955, 25.

- ^ “$3,000,000 Slum Clearance,” Washington Post. “Condemnation Of Slums,” Washington Post, December 21, 1949, 14. “D.C. Wins New Round,” Evening Star.

- ^ “Obituary: Minnie Keyes,” Washington Post, March 6, 1957, B2. Minnie Keyes, 1940 U.S. Census.

- ^ “Razing Begins On S.W. Slums,” Washington Post, September 19, 1957, A23.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)