The Short-Lived Baltimore & Potomac Railroad Station on the National Mall

In the late 1800s, people began to sour on the appearance of the National Mall and the general use of public space in Washington, D.C. In his original plans for the design of the federal capital, Pierre Charles L’Enfant called for a grand avenue that would run for one mile from a presidential monument to the Capitol building.[1] This grand avenue would include gardens and statuary in the form of monuments and artwork, later becoming what would be known as the National Mall.

In 1851, architect and horticulturalist Andrew Jackson Downing was approached by President Millard Fillmore to come up with a landscape plan for the Mall that would give some shape and style to this section of Washington. Downing came up with a detailed design, but his untimely death the next year brought a sudden end to plans to reinvigorate the Mall.[2]

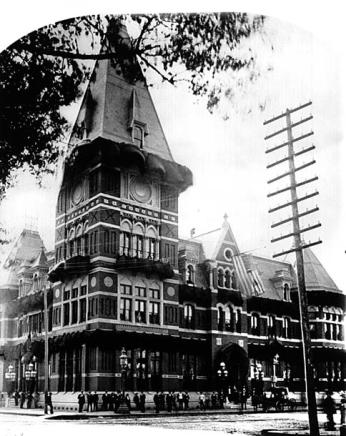

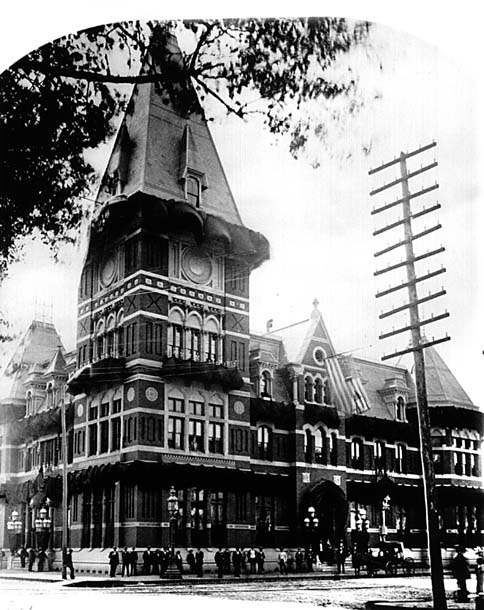

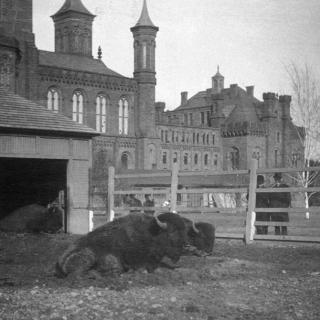

In the decades that followed, the Mall succumbed to commercial and industrial development. Perhaps the most notable addition was a railroad station belonging to the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad. This building, opened in 1873, was located on B Street (later Constitution Avenue) and 6th Street NW, where the National Gallery of Art now stands.

B&P trains ran along tracks to and from the station cut right through the Mall, but theirs was not the first railroad to do so. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the first to provide passenger service to the nation’s capital, had been operating since the 1830s. But the B&P, which was a subsidiary of the larger Pennsylvania Railroad, had the resources to establish a grand station on the Mall, while the B&O elected to move to a different location in the city.

The B&P station on the Mall embraced a Gothic architectural style, but the train shed that extended from the station was considered an eyesore. Whereas public opinion formerly believed that the railroad demonstrated the industry and ingenuity of the capital, people now believed that the mountains of coal, the noisy trains, and the black smoke destroyed the Mall’s natural beauty.[3]

A campaign was begun to redesign the Mall and remove the B&P railroad station, but not before tragedy struck. On July 2, 1881 while hurrying through the station to catch a train, President James Garfield was shot by the deranged Charles Guiteau. Garfield did not immediately succumb to the wound, but died nearly three months later after infection set in.[4]

Garfield’s assassination put an even darker shade over the station, and the movement to have it demolished gained momentum. In 1901, under the leadership of Sen. James McMillan of Michigan, the Senate Park Commission released a plan for the renovation and redesign of the National Mall. A number of individuals contributed ideas, including renowned landscape architect and designer of New York City’s Central Park Frederick Law Olmstead.

Elements of the plan included adopting a more classical architectural style, zoning for monuments, and the demolition of the B&P railroad station. There were still those who believed the station should be preserved at least for its historical significance. However, Congress passed legislation on May 15, 1902 authorizing construction for a new railroad terminal north of the Capitol. With the promise of this new Union Station, there was little need to keep the B&P station on the Mall open. It was demolished in 1908 and the tracks were torn up. The National Gallery of Art was erected in the same space and opened on March 17, 1941.

Footnotes

- ^ National Park Service, Map 1: L’Enfant Plan for Washington. https://www.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/62wash/62locate1.htm

- ^ Mary Hanlon, “The Mall: The Grand Avenue, The Government, and the People,” University of Virginia, http://xroads.virginia.edu/~CAP/MALL/chron.html

- ^ “What happened to the railroad stations on the Mall?” Histories of the National Mall, http://mallhistory.org/explorations/show/railroad

- ^ Kevin Baker, “The Doctors Who Killed a President,” New York Times, September 30, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/02/books/review/destiny-of-the-republic-…

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)