How a Confederate Woman's D.C. Home Became a Union Prison

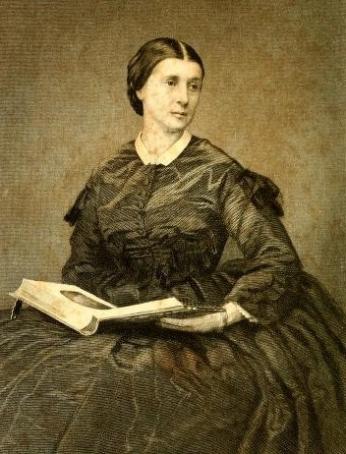

Rose O’Neal Greenhow’s house on 16th Street was always a site of political activity. Within view of the White House and in walking distance of some of the most prominent politicians in the country, it served as a meeting place for the social and political elite—from the wealthy women of Washington, like Greenhow, to senators and cabinet members.[1]

But as the Civil War heated up, so did the activity within Greenhow’s house. First, she turned the three-story, brick building into a hub of Confederate espionage. Then, it became a Union prison.

Greenhow’s political views were plainly obvious to anyone who spoke with her. Like many women in Washington at the time, Greenhow vehemently defended slavery, calling it a “benign and paternal” institution in the South, and “thoroughly identified [herself] with the cause of the South.”[2]

So when Thomas Jordan, then an officer of the U.S. Army (he later left to fight for the Confederacy), came looking for people to lead a Confederate spy ring, Greenhow was an obvious choice.[3] She had connections with people high up in both the Union and Confederate governments, and her opinions on the Confederacy were well established.

According to William Beymer, who wrote a piece about Greenhow in Harper’s Magazine in 1912, Jordan asked Greenhow what she would do to help the Confederacy. Greenhow said she would do anything, and her espionage work was underway. Jordan gave Greenhow a system for encoding messages and told her to send him dispatches, all in code and addressed to “Thomas John Rayford.”[4]

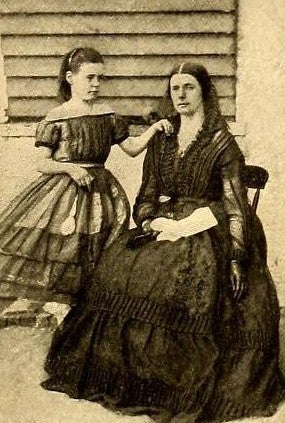

Greenhow soon set up shop in her house, sending, receiving, and storing letters about Union and Confederate missions. She used her charming personality and her political connections with Northern politicians to learn the Union’s plans, sending information through her 16-year-old courier, Bettie Duvall.[5] One of these dispatches allowed General Pierre Toutant-Beauregard to win the Battle of Bull Run.[6]

But this early success wouldn’t last. As soon as April 1861, George McClellan, the commander of the Union Army, hired Allan Pinkerton to gather “information on the movements of the traitors.”[7] That alone would not likely have made Greenhow a suspect, as Pinkerton recalled in his memoir that “little attention was paid to [women] of the old regime, as it was not deemed possible that any danger could result from the utterances of non-combatant females, nor was it considered chivalrous that resolute measures should be adopted toward the weaker sex.”[8] But then an unidentified woman reported that Greenhow seemed to be seducing federal officials in exchange for military intelligence, and Greenhow became a suspect.[9]

On August 23, Greenhow noticed that, as she was walking to her house with a neighbor, she was being watched by Union Army officers. As someone passed her by, she commented, “Those men will probably arrest me.” And sure enough, she was right. As she arrived at her door, Pinkerton walked up to Greenhow and arrested her.[10]

The arrest greatly annoyed Greenhow, who called it an assault on her constitutional rights and criticized the government for going after “helpless and defenceless women and children.”[11] (Greenhow’s child, also named Rose, was kept under arrest as well.) But none of her arguments swayed the guards into letting her go.

The arrest did not stop Greenhow. Immediately, Union officers searched her house and took every piece of paper they could find. Few would have provided the officers with much information, but one document would have proven vital to them. In Greenhow’s pocket was the cipher she used to communicate with Confederates.[12]

Quick on her feet, Greenhow moved as if to change her clothes. “Thanks to the slow movements of these agents of evil,” she wrote in her memoir, “I was allowed to go to my chamber, and then resolved to accomplish the destruction” of these papers.[13] She succeeded.

In short time, other women, too, were arrested and sent to Greenhow’s house as prisoners. The New York Times mentioned about ten women who were, at one point in time, imprisoned in Greenhow’s house. At least one of these other women was suspected by the U.S. government of assisting the Confederacy.[14]

Even detained and without the help of her cipher, Greenhow was determined to stay in communication with the Confederate spy ring. According to Pinkerton, the initial “intention of the government was to treat [Greenhow] as humanely and considerately as possible”—a charge which Greenhow vigorously refuted. But Greenhow, Pinkerton said, tried several times to “send messages to her rebel friends.”[15]

In one instance, the New York Daily Herald claimed officials seized a cake that contained inside it bribe money for Greenhow’s guards and a note containing plans for her escape.[16] The alleged “cake affair” of Jan. 1, 1862 initially caused guards merely to ban the prisoners from using windows.[17] But Greenhow would shortly be moved from her house altogether.

By the middle of February, Greenhow had been sent to the Old Capitol Building, which had been used for the past year as a prison for secessionists.[18] The embarrassment of Greenhow’s alleged attempts to communicate with Confederate forces while detained, and the widespread curiosity surrounding so-called “Fort Greenhow,” caused Pinkerton to find such a move necessary. The political activity at the house on 16th Street was finally to end.

But Greenhow’s own political actions were far from over. After being released from the federal prison, Greenhow went to Europe and then left to South Carolina, where she served as a blockade runner for the Confederacy. One day, her ship was caught in a storm while she had on a belt that was packed with gold. She fell overboard and drowned in the water.[19]

Footnotes

- ^ [1] It’s not entirely clear where Greenhow’s house is. According to Pinkerton, the house was at the corner of 13th and I Streets; however, both the Washington Chronicle and Undercover Washington describe the house as on 16th Street. Allan Pinkerton, The Spy of the Rebellion; Being a True History of the Spy System of the United States Army During the Late Rebellion (New York: G.W. Carleton & Co., 1886), 253; The Washington Chronicle, “The Female Traitors,” in The New York Times 22 January 1862; Pamela Kessler, Undercover Washington: Where Famous Spies Lived, Worked, and Loved (Sterling, VA: Capital Books, 2005), 37.

- ^ Pinkerton, The Spy of the Rebellion, 250; Rose O’Neal Greenhow, My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington (London: Richard Bentley, 1863), 13.

- ^ William Beymer, “Mrs. Greenhow,” in Harper’s Magazine March 1912, 563.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Cate Lineberry, “The Wild Rose of Washington,” The New York Times, 22 August 2011.

- ^ Beymer, “Mrs. Greenhow,” 565.

- ^ Cate Lineberry, “The Union’s Spy Game,” The New York Times, 15 August 2011.

- ^ Pinkerton, The Spy of the Rebellion, 251.

- ^ H. Donald Winkler, Stealing Secrets: How a Few Daring Women Deceived Generals, Impacted Battles, and Altered the Course of the Civil War (Naperville, IL: Cumberland House, 2011) , 12.

- ^ Lineberry, “The Wild Rose of Washington.”

- ^ Greenhow, My Imprisonment, 40.

- ^ Ibid., 56, 61.

- ^ Ibid., 61.

- ^ “The Female Prison at Washington,” The New York Times, 17 January 1862.

- ^ Pinkerton, The Spy of the Rebellion, 269.

- ^ Greenhow, My Imprisonment, 172.

- ^ “Female Prison at Washington,” The New York Times.

- ^ “The Old Capitol Buiding,” The New York Times, 19 April 1862.

- ^ Pinkerton, The Spy of the Rebellion, 269-70.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)