The Election of 1828: It's Always Been Ugly

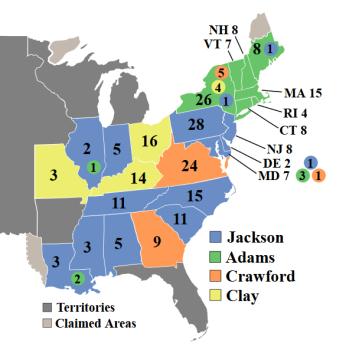

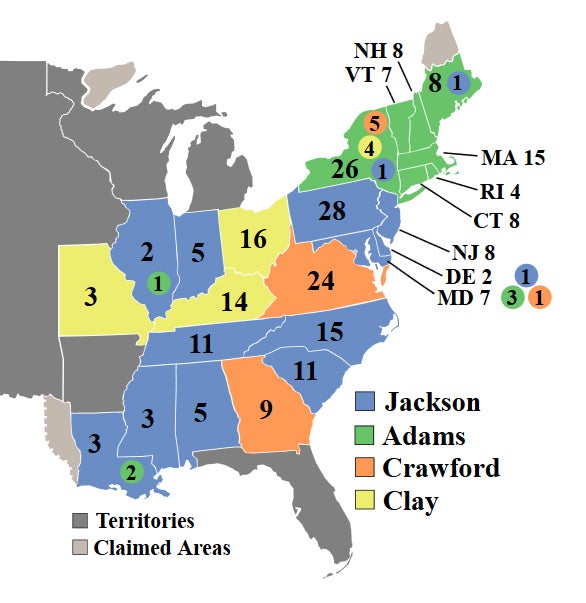

As the presidential election of 1828 approached, the nation’s emotions were running high. Andrew Jackson, the former Governor of Tennessee, was to challenge incumbent President John Quincy Adams. This was a partial rematch of the controversial four-way contest of 1824. Jackson won the most popular and electoral votes, but because no candidate won a majority, the election went to the House of Representatives, who chose second-place finisher John Quincy Adams.[1] Jackson and his supporters were furious. Calling it the “Corrupt Bargain,” Jackson’s supporters accused fourth-place candidate Henry Clay of selling his supporters to Adams for the job of Secretary of State. This set the stage for the most vicious campaign ever seen at that point in American history.

1824’s divided election was a result of the splintering of the Democratic-Republican party, which had been, for the better part of a decade, the only major political party in America. The election results only deepened the party’s divides. As soon as Andrew Jackson was defeated, he began planning for his 1828 run, contacting and marshaling political allies even on his journey home from D.C. after the House’s vote.[2] Tennessee’s legislature re-nominated Jackson for president almost immediately after the election results were announced; it was clear that the next election would be a rematch between Jackson and Adams.

By 1828, the Democratic-Republican Party had collapsed into two factions. John Quincy Adams was the candidate of the National Republicans (no relation to the modern party) while Jackson ran on the Democratic ticket (absolutely related to the modern party). The National Republicans were in favor of centralized government and protective tariffs. In the Ohio nominating convention, the party went so far as to say that “the hand of government never touches us, but to promote the general good."[3] The Jacksonians, on the other hand, were a bubbling populist movement. They declared that centralizing government was the first step to monarchy, and that tariffs were the cause of the nation’s economic woes. Jackson himself kept his policy positions intentionally vague, except for his plan to purify the Departments.[4]

The split between the candidates could not have been clearer. Jackson was the former Governor of Tennessee, a former general in the War of 1812, and a man of the people. Adams was the Massachusetts-born son of a former president, who switched parties multiple times in the past. To Adams’ supporters, Jackson was a dangerous man, unqualified and possibly unhinged.[5] To Jackson’s supporters, Adams was a corrupt elitist who stole the previous election. Both sides viewed the other candidate as a threat to the republic.

This election is often referred to as the birth of modern campaigning, and the total war that that implies. The campaigns of both sides’ supporters were overwhelmingly focused on the character of their opponent, rather than the policies at hand. The nominating conventions were long screeds against Jackson, Adams, and Henry Clay by name. Both sides aggressively courted individual politicians and newspaper owners with promised favors, and each denounced the other for doing so. Jackson supporters in the Senate began to focus on passing plans that were amenable to key swing states, like New York and Pennsylvania, in the hopes of garnering their votes.[6] Jackson himself focused on poaching politicians from Adams’ side; Jackson’s running mate was Adams’ sitting vice president, John C. Calhoun.[7] Jackson also had the support of the popular New York Senator Martin Van Buren.[8]

Brand-new newspapers began to pop up all over the country; the number of newspapers in the country nearly doubled between 1824 and 1828, with partisan daily papers providing slanted facts for either side.[9] No holds were barred. Jackson was accused of being a war criminal, an adulterer, and a murderer; Adams was painted as dreaming of a crown, and an aristocratic threat to democracy itself.

The Democrats’ main line of attack was on the idea that Adams and Clay had conspired to steal the previous election from Jackson. They compared Adams’ supporters to the Federalists, the Loyalists, and monarchists.[10] They accused the “federalists” of intentionally dividing the country by talking about votes for free black Americans, and criticizing the white slave-holding elite of the South.[11] They also attacked Adams for the acts of his father’s administration, in particular the Sedition Act of 1798, which criminalized “false” speech against the government.[12] In his first address to Congress, Adams said that politicians should not be “palsied by the will of our constituents”; this was a quote that came back to haunt him, particularly as he had already been criticized as cloistered and elitist.

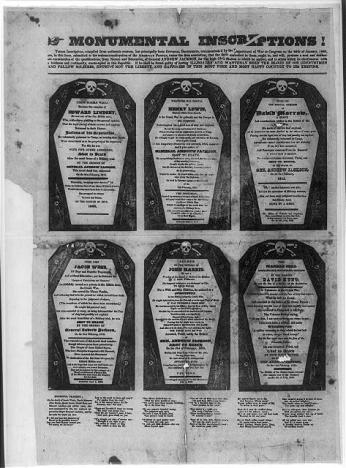

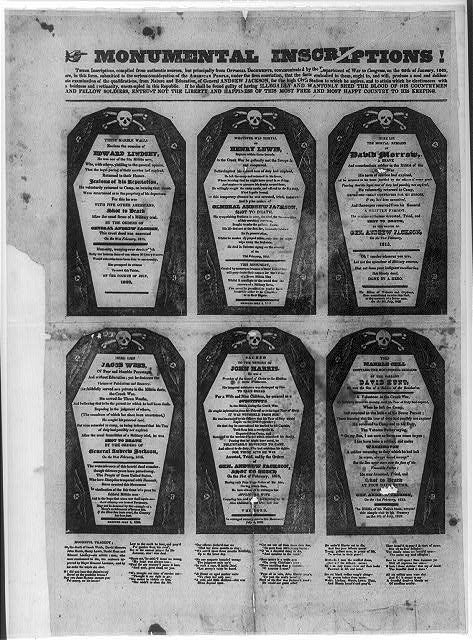

For their part, Adams’ supporters worried Jackson could be an American Caesar, a militarizing force leading to authoritarian rule. They attacked his bloody deeds in the war, most famously with the “Coffin Pamphlets,” which condemned Jackson for executing six militiamen in the War of 1812. They included biographies of the men he executed, pictures of six coffins at the top, and for some reason a sixteen-stanza poem condemning his actions.[13] Other editions of the pamphlets also condemned Jackson for killing “men, women, and Children” in his raids on Native American settlements. Jackson’s status as a war hero had launched his political career, so this was an attack on the foundation of his reputation. The pamphlets were so ubiquitous and overwrought that a satirical pamphlet was published accusing Jackson of cannibalism in the same style, and predicting that if he was ever displeased with Congress, he would “march to the Capitol...take it upon his shoulders...and hurl Capitol, Congressmen, and all, into the Potomac river[.]"[14]

The campaign was also characterized by baseless attacks on the candidates’ personal lives. Democrats accused Adams of being a spendthrift, spending money on gambling equipment in the White House (this turned out to be a billiards table). For their part, Adams’ supporters attacked Jackson for his marriage. He had gotten married to a divorcee, Rachel Donelson, when they were both under the impression that her previous marriage had been annulled; this was in fact not legally the case. The two of them got remarried as soon as they found out about the discrepancy. The Adams camp seizing on this, smearing Jackson as an adulteress’ “paramour.” Some Adams supporters went even further, claiming Jackson’s mother was a prostitute.[15]

When November rolled around, Jackson won the election decisively, winning almost every electoral vote outside New England.[16] Jackson’s supporters were ecstatic. No longer would their leaders be statesmen from Massachusetts and Virginia; the war hero from Tennessee was in the White House.

Things between the candidates remained icy. Jackson refused to meet with Adams after the election; in turn, Adams refused to attend Jackson’s inauguration. Rachel Jackson had also died two months before inauguration day; her husband privately blamed Adams and his partisans’ muckraking for her illness.

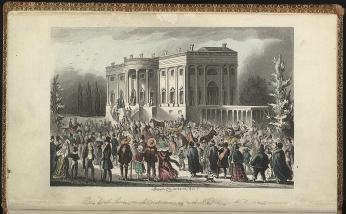

People flooded D.C. for the inauguration - despite poor weather, anywhere between ten and twenty thousand people showed up, an enormous crowd for the time. In true populist style, Jackson refused to have a military parade for his inauguration, opting instead to walk from his hotel to the Capitol. The organizers scrambled to invent some kind of order for the statesmen, citizens, and Revolutionary veterans who were to follow him. Extraordinarily for the time, “persons of every rank in life (and of almost every nation and complexion)” walked side by side.[17]

Following his speech, the people flooded up the stairs of the Capitol to shake Jackson’s hand and congratulate him. One witness recounted:

“The living mass was impenetrable...he mounted his horse which had been provided for his return (for he had walked to the Capitol) then such a cortege as followed him! Country men, farmers, gentlemen, mounted and dismounted, boys, women and children, black and white. Carriages, wagons and carts all pursuing him to the President’s House."[18]

That evening, Jackson had a party in the White House open to the public. Jackson was almost crushed against a wall by admirers, and had to be escorted out in a football-style wedge to get through the crowd. He ended up spending the night in a hotel in downtown DC, unable to sleep in his own bed because of the celebration of his victory.[19]

In later elections, John Quincy Adams’ faction became the National Republicans (no relation), and later on the Whigs; Jackson’s followers became the Democratic Party. The former was a prominent force in national politics through the 1850s, while the latter has been one of the two major American parties ever since.

More Information

- Jackson would later have further revenge for the “Corrupt Bargain” of 1824. In the election of 1832, he faced Henry Clay, the other man who helped deny him the presidency - and beat him handily as well.

- Joel Silbey’s The American Party Battle is an extremely valuable resource for understanding the positions and rhetoric of the political parties of the day (the Democrats vs. the National Republicans, and later the Whigs).

- For more on the more destructive aspects of Andrew Jackson’s legacy, check out Steve Inskeep’s book Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab.

Footnotes

- ^ The American electoral system strikes again! This rule, FYI, is still in place.

- ^ Steve Inskeep, Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab, (New York: Penguin Books, 2015), 167.

- ^ “Proceedings and Address of the Convention of Delegates...to Nominate...John Quincy Adams,” (Columbus, OH, 1827), p. 7.

- ^ Robert V. Remini, “Election of 1828,” in The Coming To Power, p. 73.

- ^ ‘[Jackson’s] whole life has evinced an arbitrary temper, not congenial to our institutions, and justifying fears of disastrous consequences, should the sword be entrusted to his hands”; “already so degenerated as to look, without horror, upon the possibility, of giving ourselves a master, and submitting our necks to the yoke?” The American Party Battle: Election Campaign Pamphlets 1828-1876: Volume I 1828-1854, ed. Joel H. Silbey, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), 9.

- ^ Robert V. Remini, “Election of 1828,” in The Coming To Power, p. 78-79

- ^ Calhoun actually ran with Jackson in 1824, and was elected even though Jackson lost to Adams, because when there is no clear winner in the Electoral College, the House picks the President, but the Senate picks the Vice President. Special thanks to the American electoral system!

- ^ Martin Van Buren became Jackson’s vice president in 1832 and was elected president himself in 1836. In that election, Van Buren’s opponents intentionally tried to emulate the strategy that kept Jackson out of the White House in 1824: they ran four candidates, each of them popular in different regions of the country, in the hope that no candidate would gain a majority and the decision would rest with the House of Representatives. The strategy failed; Van Buren simply won a majority of electoral votes. No one has tried this since.

- ^ Inskeep, Jacksonland, p. 173.

- ^ “Proceedings and Address of the New Hampshire Republican State Convention of Delegates Friendly to the Election of Andrew Jackson....Assembled at Concord, June 11 and 12, 1828,” (Concord, 1828), from The American Party Battle, ed. Joel H. Silbey, (Cambirdge: Harvard University Press, 2009), p. 56.

- ^ “Proceedings and Address of the New Hampshire Republican State Convention” from The American Party Battle, p. 77.

- ^ “Proceedings and Address of the New Hampshire Republican State Convention” from The American Party Battle, p. __.

- ^ The final two stanzas are as follows: “Sure he will spare! Sure Jackson yet/Will all reprieve but one - / O hark! those shrieks! that cry of death!/The dreadful deed is done. // All six militia men were shot!/And O! it seems to me/A dreadful deed - a bloody act/Of needless cruelty.” This is a baffling choice to me, since I sincerely doubt anyone unconvinced by the rhetoric in the pamphlet would be swayed by a poem, especially one of this quality.

- ^ “Supplemental account of some of the bloody deeds of General Jackson, being a supplement to the ‘Coffin hand bill’...”, pub. 1828.

- ^ Robert V. Remini, “Election of 1828,” in The Coming To Power, p. 81.

- ^ If you want to get into the specifics, Jackson won the electoral vote 178-83, and the popular vote 56%-43%. Locally, Virginia gave its 24 electoral votes to Jackson, and Maryland split its vote, giving 6 to Adams and 5 to Jackson.

- ^ Richmond Inquirer, “The Inauguration. Washington, March 5,” March 10, 1829, p. 2.

- ^ Rex M. Oppenheimer, Washington D.C.:The Concience of America, p. 43.

- ^ Inskeep, Jacksonland, 181-2.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)