Fat Men's Clubs of D.C.

The body-acceptance movement is nothing new. The National Society to Advance Fat Acceptance has been around since the 1970s, and similar organizations are gaining traction across the country. People have been stating the case that body fat is nothing to be ashamed of for far longer than 40 years, however.

In the late 19th century, there were actual fat men’s clubs in “every state in the Union”[1] and the nation's capital. At the time, being overweight was sought-after and prized by certain social classes. In the eyes of many, obesity was still a sign of wealth and prestige, and members would intentionally pack on the pounds at the time of membership renewal in order to remain eligible. They were proud of their weights, even boasting about how much they had gained each week. Membership rolls featured influential people, including policemen and politicians.

Washington, D.C. boasted several fat men’s clubs, girth and power going hand in hand back in the day. The Jolly Fat Men’s Club was the most popular. Dating back to the 1870s, this club was a celebration of corpulence that had a large presence in the town. The members of the club were more often than not wealthy, and - as the name suggested - of genial character. The simultaneous comradely and well-to-do natures of the Club’s members can be seen in an 1887 ad for a clothing sale. The shop-owner was having a clearance sale on small suits, and gave the reason:

“The Fat Men’s Club have made a run on us and purchased all the large sizes, and gentlemen wearing...from 33 to 38 breast measure, can have any of these sizes at...just one-half the original price.”[2]

The ad practically begged thin men to come and pick at the leftovers of the Club.

The D.C. fat men’s club scene was wildly popular. Their events and excursions were extraordinarily well-attended. In 1891, they began chartering annual outings to River View, where they would picnic, barbecue, and participate in various games. Their third such trip, in the summer of 1893 was particularly spectacular; notably, as reported, “[t]hree steamers were chartered for the event and made seven trips, transporting 6,200 people.”[3][4] Fat and thin alike were welcome. Athletic events, most only open to fat men, were a mainstay at these outings; they included footraces, three-legged races, and even dancing competitions.[5] Baseball games pitting fat and skinny men against one another were also popular. That same year, the Jolly Fat Men’s Club held its first annual parade.[6] Over one hundred of the club’s 200 members at the time turned out for the parade; they rode in carriages instead of walking the parade route.

Logically enough, a great deal of the Club’s activities revolved around eating. The club hosted banquets, barbecues, and clam bakes. The weight-celebration style of the day involved being proud and unashamed of food. Weigh-ins after the Club’s annual clam bakes were routine for members.[7] These records were printed in the newspaper, and their weights were a point of boasting. This pride in one’s weight was not limited to the men of the club; women were among the record-holders as well. A Mrs. Oscar Church was a proud participant at the clam-bake in 1894, her weight increasing to a respectable 367.5 pounds.[8]

Popular at the time was the idea that fat men were, by nature, better-tempered and more kindly than their skinnier neighbors. The idea that the better angels of our nature rather resemble cherubs was a key component of the Clubs’ ethos. One club’s unofficial motto was “we’re fat and we’re making the most of it”; another was “I’ve got to be good-natured - I can’t fight or run.”[9]

Despite their good-natured mottoes, however, the District’s fat men’s clubs got up to a good deal of mischief. In 1894, a brawl between the Jolly Fat Men’s Club and the Fat Men’s Beneficiary Association, which was a splinter group that broke off after a financial dispute. The two groups had scheduled their annual barbecues for the same day, and came to blows when there was a territorial dispute concerning picnicking areas.[10] On another occasion, the Club was busted for serving beer on a Sunday (which, at the time, was illegal). The police raided the headquarters, only to find eight police officers, three in uniform, drinking with the rest of the club.[11] Beer-gutted policemen aside, the halls of the Fat Men’s Clubs were filled with many men of wealth and prestige; they lionized Shakespeare and Caesar, whom they claimed for the ranks of the fat.[12]

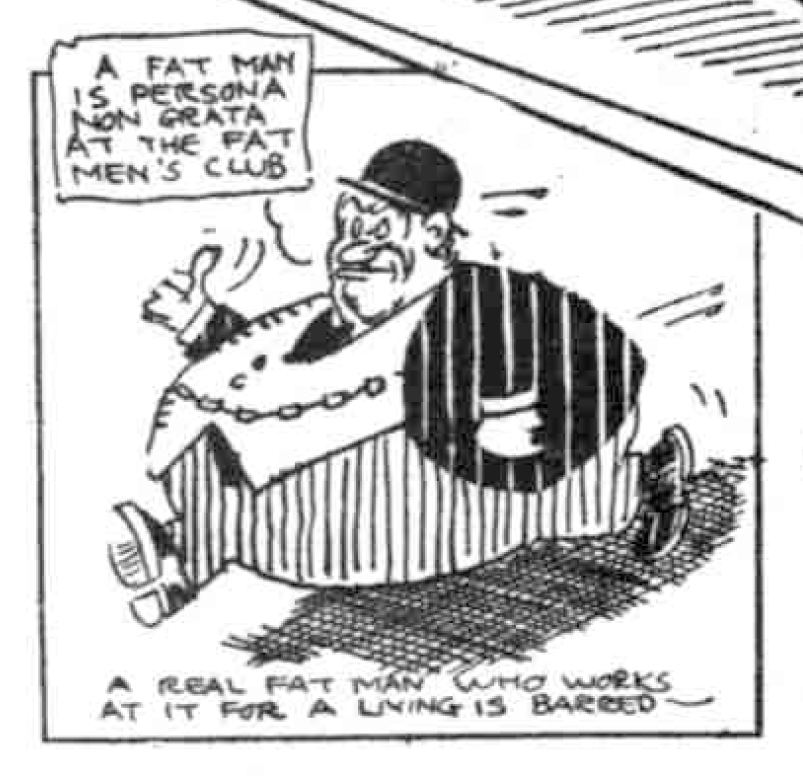

As time went on, however, obesity acquired more and more stigma.[13] Many clubs, while not outright ridiculed, were covered with a mocking tone by the press. [14] Case and point: in 1892, the Evening Star devoted several inches of print space to report on an unlucky member of a local fat men’s club who ripped his pants while participating in a bicycle race.[15] In the late 19th century, some civil service jobs started refusing to hire obese people, because they were thought to be lazy.[16] In the 1920s, William Johnston, author of The Fun of Being a Fat Man, reported being constantly bombarded with “unsolicited advice on ‘How to Get Thin’”[17] perhaps because the Surgeon General began issuing warnings declaring obesity unhealthy. In the subsequent decades, Fat Men’s Clubs declined in popularity and all but disappeared as the nation tightened its belt during the Great Depression and World War II.

Footnotes

- ^ William Johnston, The Fun of Being A Fat Man (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, & co., 1922), 80. Another quote from this same page: “Who ever heard of a Thin Men’s Club? Who would want to belong to it if there were one? Fat Men’s Clubs get together and have wonderful times, but if a lot of thin men should meet, when they weren’t querulous, they would be sure to be fighting…” (80)

- ^ Evening Star, July 27, 1887, p. 1.

- ^ Kerry Segrave, Obesity in America, 1850-1939: A History of Social Attitudes and Treatment, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2008), 40.

- ^ The Evening Star declared the day a “colossal success”; it’s unclear if this was a cruel joke or simply the work of an unvigilant copyeditor. “Along the Wharves,” Evening Star, June 19, 1893, p. 3.

- ^ “Along the Wharves,” Evening Star, June 19, 1893, p. 3.

- ^ Segrave, Obesity in America, 40.

- ^ Kerry Segrave, Obesity in America, 1850-1939: A History of Social Attitudes and Treatment, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2008), 40.

- ^ Seagrave, Obesity in America, 40.

- ^ Tanya Basu, “The Forgotten History of Fat Men’s Clubs,” NPR, http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/03/07/469571114/the-forgotten-….

- ^ Segrave, Obesity in America, 1850-1939, 40.

- ^ Kerry Segrave, Obesity in America, 1850-1939: A History of Social Attitudes and Treatment, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2008), 42.

- ^ Johnston, The Fun of Being A Fat Man, 79.

- ^ Segrave, Obesity in America, 1850-1939, 62.

- ^ Other coverage was downright tautological. The Evening Star reported on one soiree: “The Jolly Fat Men’s Club gave a banquet last night. All present were consistent members of the club. Everybody was fat and jolly.” [“Jolly Fat Men’s Club,” Evening Star, January 11, 1894, p. 8.]

- ^ “Many Country Runs,” Evening Star, June 18, 1892, p. 9. Imagine having an article in the newspaper written about your public humiliation. I feel kind of cruel dredging it up here; my point was to show how the press generally mocked the Fat Men, but in a way I’m participating in it, 142 years later.

- ^ Segrave, Obesity in America, 1850-1939, 43.

- ^ Johnston, The Fun of Being A Fat Man, 63.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)