A Forgotten Fight? Kicking Bear and the Dumbarton Bridge

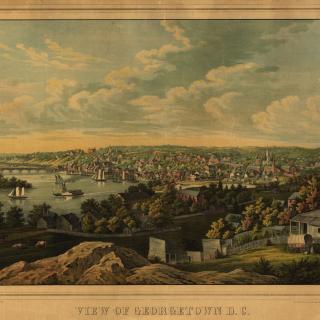

Dumbarton Bridge is nestled between Georgetown and Dupont Circle. As it spans Rock Creek, the bridge curves northward, gracefully joining two misaligned stretches of Q Street. Bronze Buffalo guard the approaches and 56 identical sculptures of a Native American man line the base of the bridge’s second tier of arches. Chosen to provide a distinctly “American character,” these design features are reflective of an artistic movement that idealized European settlement and western expansion.[1] Ironically, the man depicted by the replicate busts spent his entire life fighting European settlement.

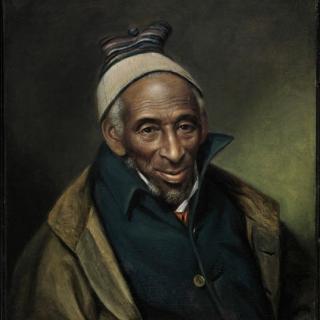

Matȟó Wanáȟtake, also known as Kicking Bear, was born in an Oglala Lakota community near Pine Ridge, South Dakota in 1846. He was identified as a capable fighter from an early age and at 20, took charge of his own group of fighters in the War for the Black Hills, or the Great Sioux War. After the war, Kicking Bear put down arms and began to resist settlement through other means.

In 1889, Kicking Bear was sent on a pilgrimage to Nevada where he met with a Northern Paiute holy man by the name of Wovoka. Wovoka was the founder of a pan-Native religious movement called Ghost Dance, which is summarized by Black Elk in Black Elk Speaks:[2]

“[Wovoka] told [his students] that there was another world coming, just like a cloud. It would come in a whirlwind out of the west and would crush out everything on this world, which was old and dying. In that other world there was plenty of meat, just like old times; and in that world all the dead Indians were alive, and all the bison that had ever been killed were roaming around again… If [people danced the Ghost Dance] they could get on this other world when it came, and the [European Settles] would not be able to get on, and so they would disappear.”[3]

Kicking Bear staged the first Lakota Ghost Dance and soon developed a reputation as a distinguished holy man.[4]

Though Ghost Dance was explicitly nonviolent, the United States Government became fearful of the highly successful movement.[5] Washington sent troops to Standing Rock where they found and arrested Kicking Bear and other prominent figures.[6] Kicking Bear and his fellow captives were offered release provided they join the 1891-92 European Tour of Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. Kicking bear agreed but became enraged with the way in which the show depicted Native Americans. He quit the tour and was imprisoned once again.[7] The U.S. released Kicking Bear in the summer of 1892, by which time his national reputation as a headstrong leader was well established.[8]

On February 14, 1896, Kicking Bear was one of five men elected to travel to Washington and air grievances against the United States Government and European Settlers.[9] The delegates arrived in D.C. on February 27 and took up residence in Hotel Le Fétra. Over the course of their three week visit, the delegates met with the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Congressional Committees on Indian Affairs. Their primary demands were that the United States uphold prior treaties and that it stop interfering with local law enforcement and Lakota trade practices.[10] Transcripts from these meetings show that Kicking Bear was by far the most vocal and openly critical member of the delegation.[11]

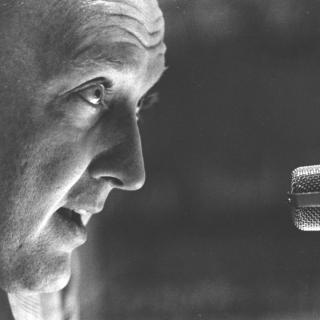

As well as meeting with government officials, the Lakota delegates were toured around the city. It was on one of these outings that Kicking Bear was introduced to anthropologist James Mooney. At the time, Mooney was working for the Bureau of American Ethnology, which was charged with developing the Smithsonian Institutions’ ethnographic archives. According to a 1991 article from Smithsonian Magazine, the Bureau made over 500 life masks of “Native Americans, Africans, Polynesians, Asians, and Europeans” (as well as casual visitors to the Smithsonian, politicians, and several anthropologists) but Kicking Bear was one of the first and most famous people to be cast.[12]

The process took several hours. The Smithsonian anthropologists began by coating Kicking Bear’s face with petroleum jelly and placing straws in his nostrils before applying a thick layer of plaster and leaving it to set. After the Lakota delegation’s departure on March 14, the Smithsonian announced that it would cast the plaster life mask in bronze, but no such casting took place.[13] Instead, the Smithsonian painted the life mask, fitted it with a wig and placed it atop a figure dressed in Kicking Bear’s own buckskin clothing. The figure was then put on display in the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.[14] By 1950, Kicking Bear’s clothes were falling apart and were put into preservative storage and the figure was moved to another exhibit and renamed “Sioux Warrior.”[15] From 1950 onwards, museumgoers would have no idea that the face of this figure was a casting of one of the most famous Lakota leaders of his time.

Kicking Bear Passed away in 1904. A year later, talks of a new bridge over Rock Creek got underway. Washington had experienced a massive population boom and traffic over Rock Creek had become unmanageable.[16]

Construction on a new bridge over the Rock Creek ravine got underway in 1910. The bridge itself was designed by Glenn Brown, a secretary of the American Institute of Architects. Sculptor Alexander Phimister Proctor was hired to provide a distinct “American character” to the bridge so as to set it apart from the unadorned Roman aqueducts on which it was modeled.[17] Of course, while bridges are inherently functional structures, effort was poured into the bridge’s stylistic details. Not only was Washington’s “City Beautiful” movement still in full swing, affluent Georgetowners believed an ugly bridge would negatively impact property values and demanded an elegant structure.[18]

Like many of his contemporaries, Proctor was captivated by the notion of the “vanishing west.” Proctor “was born during the frontier period of the United States and grew up in Colorado during the best of it.”[19] Proctor’s art was undoubtedly influenced by childhood “tales of the early frontier West, of Indian fights, and of bears.”[20] As Metropolitan Museum of Art scholar Thayer Tolles notes, Proctor’s first hand experience as a European settler informed countless works that oxymoronically grieved the loss of the “American Eden,” while also reinforced “the notion that continental expansion by Euro-Americans was preordained in order to spread democratic principles as well as social and economic ‘progress.’”[21] For artists like Proctor, western motifs represented something quintessentially American. When tasked with providing an “American character” to the bridge, Proctor cast four bison, an animal which western settlers had driven to near extinction. After receiving Kicking Bear’s life mask on loan from the Smithsonian, he used it as the model for 56 identical busts, which were then placed below the bridge’s corbels.[22]

While little was made of it at the time, Proctor’s decision to appropriate Kicking Bear’s likeness has a healthy dose of irony. The Native American leader had been best known for his resistance to the U.S. government’s advance into tribal lands. In fact, Kicking Bear’s life mask was cast while he was on a trip to Washington denouncing western expansion. Yet, after his death, the mask was used for an architectural pursuit that is but one of many artistic pieces of the period to present the “vanishing west” as an unfortunate side effect of “preordained” expansion.

Footnotes

- ^ Brown, Glenn and Bedford Brown. “The Q Street Bridge, Washington D.C.,” The American Architect 108, no. 1 (1915): 277.

- ^ Neihardt, John G.. Black Elk Speaks. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1932. 181.

- ^ Ibid.,178-180.

- ^ Ibid., 182.

- ^ Philbrick, Nathaniel. The Last Stand. New York City: Penguin USA, 2010. 293.

- ^ “Buffalo Bill Indians.” The New York Times. Apr. 24, 1892. The William F. Cody Archive.

- ^ Neihardt. Black Elk Speaks. 191.; “Buffalo Bill Indians.” New York Times, Apr. 24, 1892.

- ^ “Buffalo Bill Indians.” New York Times, Apr. 24, 1892.

- ^ “Selected the Indian Delegates.” Omaha Daily Bee. Feb. 15, 1896. Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

- ^ “Big Sioux Here.” The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), Feb. 28, 1896. Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

- ^ Duncan, David Ewing. “The Object at Hand.” Smithsonian Magazine 22, no. 6, Sept., 1991. History Reference Center.

- ^ Duncan “The Object at Hand.”

- ^ “Art and Artists.” The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), Mar. 21, 1896. Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

- ^ Duncan, “The Object at Hand.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Georgetown Citizen's Association asked the city to fill in the then trash-laden Rock Creek ravine and build a tunnel to relieve traffic. When the plan for a tunnel was deemed too costly, residents suggested the city provide a quick fix by dismantling either the Thompson Bridge or the Old Calvert Street/Woodley Lane Bridge and rebuilding it in Georgetown. Unsurprisingly, this alternative was also rejected and Georgetowners were told to wait for the construction of a new bridge. (See: “Georgetown Will Ask for Tunnel.” The Washington Times, Jan. 10, 1905. and “To Ascertain Cost and Feasibility of Moving Bridge Across Rock Creek” The Evening Star, Feb. 9, 1905.)

- ^ Brown, Glenn and Bedford Brown. “The Q Street Bridge, Washington D.C.,” The American Architect 108, no. 1 (1915): 273-278.

- ^ “Georgetown Will Ask for Tunnel.” The Washington Times, Jan. 10, 1905.

- ^ Proctor, Alexander Phimister. “Sculptor in Buckskin: An Autobiography.” Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 1971. 202.

- ^ Ibid., 22.

- ^ Tolles, Thayer. “Bronze Statuettes of the American West, 1850–1915.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2006. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bsaw/hd_bsaw.htm.

- ^ Boucher, Jack . “Detail of Indian Sculpted by A. Phimster Proctor from Life Mask of Chief Kicking Bear.” 1993. Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/dc0775.photos.047880p/

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)