All's Wright that Ends Well: The Pope-Leighey House of Northern Virginia

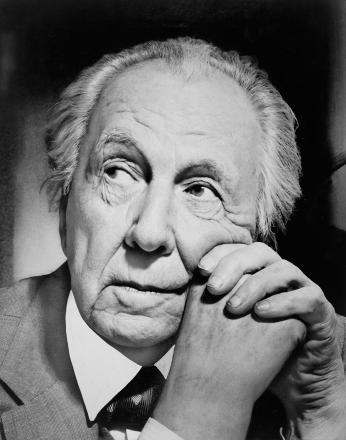

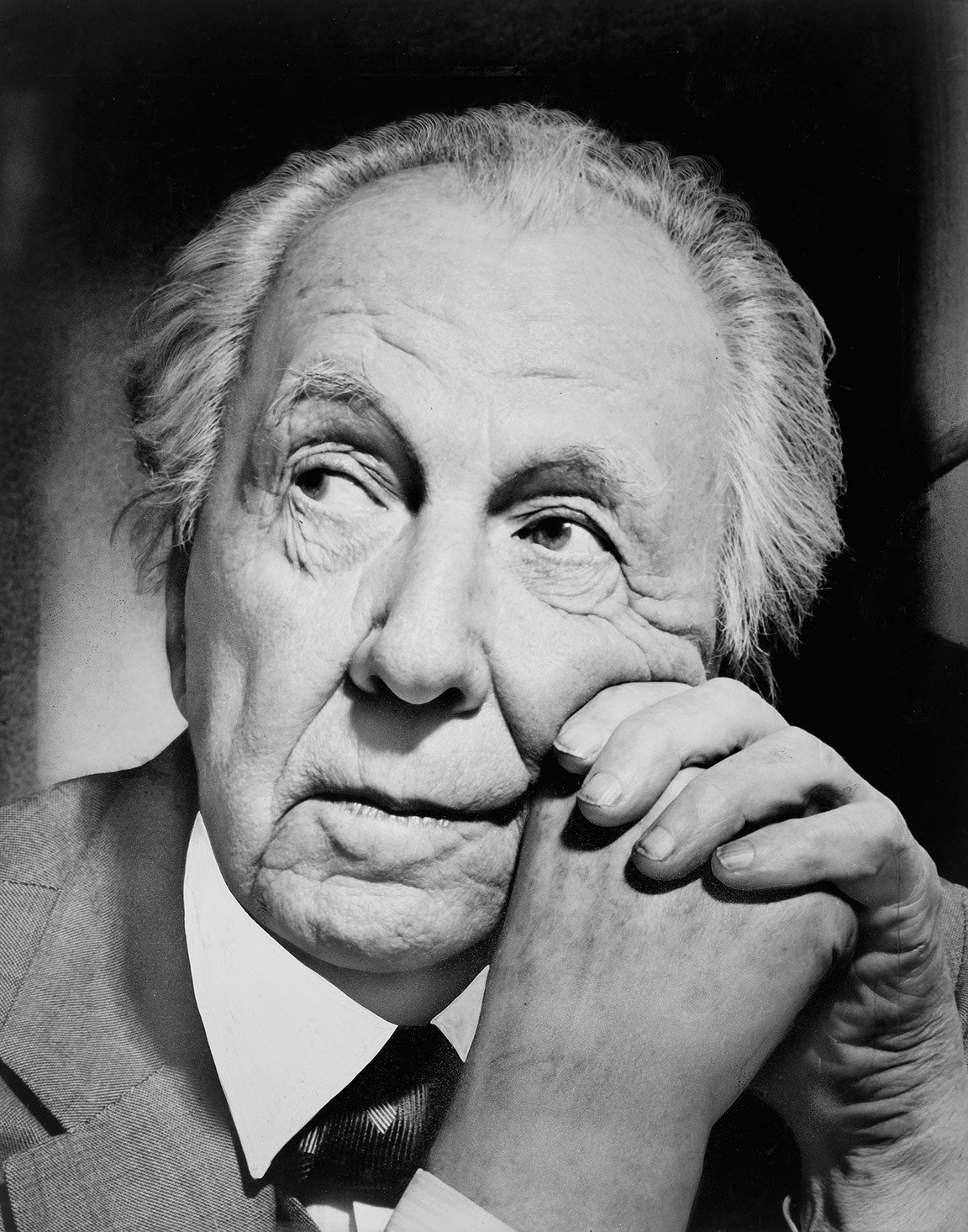

The name Frank Lloyd Wright may bring to mind New York City’s Guggenheim Museum, residences in Chicago, the Midwest, and deserts of Arizona. He built iconic modern structures all over the country; even Northern Virginia can boast a unique connection to the renowned American architect.

Born in 1867, Wright came of age in Wisconsin and knew early on that his future lay in architecture.[1] When he was twenty years old, he set off to Chicago and found work under the famed Louis Sullivan, a pioneer in the invention of skyscrapers. Where Sullivan built upwards, Wright, by contrast, was drawn to horizontality and opened his own office in 1893 to independently pursue the design of a truly American architecture.[2]

For Wright, this called for a landscape of vast, open prairies and his work during the turn of the 20th century became aptly known as the Prairie Style.[3] Acutely attentive to evolving the relationship between domestic and natural features, the architect simultaneously observed a bleak change in the country’s economic landscape during the Great Depression.[4] The 1930s inspired Wright to create an egalitarian style known as Usonia: houses that balanced beauty with affordability for the average American.[5]

It was also in the ‘30s that two such average Americans would spark an exceptional chain of events in the national capital region.

Loren Pope and Charlotte Swart met while studying at DePauw University in Indiana.[6] They married in New Jersey in 1936, then returned to their new home in the D.C. suburbs.[7] Loren began his career at the Evening Star, and the couple spent their evenings discussing plans to build a house in Falls Church.[8] The dream, however, would not be cheap and Loren was earning only $50 a week.[9] The Popes researched home construction loan prospects but with little success. “My last resort,” Pope recounted, “was the Evening Star, which financed homes for its employees. The Star offered to lend me $5,700, to be taken out of my pay at $12 a week.”[10] As historian Stephen Reiss explains, the newspaper’s program “was quite amazing when you think about it today, but they were encouraging employees to stay in the area.”[11]

The Popes purchased a one-and-a-third acre lot with the loan and agreed to build a “picket-fenced Cape Cod style home.”[12] Though comfortable with the plan, Loren still kept an open mind when a coworker suggested he look into Frank Lloyd Wright.[13] Pope skimmed, unimpressed, through a Wright portfolio at the public library, but soon experienced a dramatic change of heart.[14]

Time magazine featured Wright on the cover of its January 1938 issue, publishing a comprehensive survey of his work up to that point. Entitled “Usonian Architect,” the article explained, “Usonia is Frank Lloyd Wright’s name for the U.S.A.” Wright had recently materialized his philosophy of affordable domestic architecture in “the one-story, six-room, $5,500 house which he finished last month for Herbert Jacobs, a newspaperman in Madison, Wis.”[15] The Jacobs House would be the first of about 60 Usonian homes Wright built for professors, artists, schoolteachers, middle-class businessmen, journalists, and others - before his death in 1959.[16][17] (The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation features a number of them on their website.)

Pope was intrigued to learn a newspaperman like him could commission a Wright house. He immediately purchased and devoured the architect’s 1932 An Autobiography and, after attending Wright’s lecture in October with his wife, sat down to pen a letter.[18]

Several drafts and months later, his heart pounding, Pope mailed it. “Dear Mr. Wright,” he divulged in August 1939, “There are certain things a man wants during life, and, of life. Material things and things of the spirit. The writer has one fervent wish that includes both. It is for a house created by you.”[19]

The following three weeks, Pope went daily to the post office, anxiously checking for a response. Wright’s succinct reply finally came: “Of course I’m ready to give you a house.”[20]

While it was common for Usonian commissions to begin with letters from hopeful clients,[21] the 28-year-old copy editor and 72-year-old architect developed a remarkably sympathetic relationship during construction, projected to cost about $7000.[22] “When the house was about half done,” Loren narrated, “and as we talked during lunch he said, ‘Loren, this house is costing you too much; forget about the rest of the fee.’ His fee was ten percent of the cost and I had paid about half.”[23]

Pulling largely from the Herbert Jacobs House design and relying on Pope’s description of the plot, Wright aspired to capture “the sense of a happy, cloudless day.”[24]

Construction took nine months, and in March 1941, Loren, Charlotte and their two-year-old son, Ned, moved in.[25] Loren would vividly recall the L-shaped “big small house” in a 2016 interview. The red concrete floor doubled as the home’s radiant heater “by virtue of the hot water pipes underneath.”[26]

“The house has brick supporting piers and cypress walls. For light, ventilation, and decoration, the house has a patterned ribbon of clerestory windows between the top of the wall and the ceiling. You can sit by the fireplace at night and see the stars. There is no paint or plaster, and no masking of any material. The finish, both outside and in, is clear wax, a treatment that complements the beauties of brick and wood. The house gives you a sense of protection, but never of being closed in, and of leading you beyond where your eyes can see. The honest use of materials satisfies the urge you feel when you think you would like to have a log cabin or a rustic hide-out in the mountains. Altogether, it is a soft, warm symphony of charm.”[27]

It was “an extraordinary house for an ordinary price,” he resolved admiringly, pointing back to Wright’s commitment to his Usonian mission.[28]

Unfortunately, for all its marvel and wonder, the house could not protect the Popes from tragedy. In the later days of the spring they moved in, baby Ned embraced his newfound knack for walking. He roamed the nearby woods with his friend, a little girl who lived next door. With the innocent curiosity of any young child, “his attention had been attracted by the ducks in the pond” and he waddled into the water.[29] Although not very deep, the boy drowned before his parents could reach him. The funeral was held that May.

Weeks later, the Popes gave birth to Loren Jr., and then to Penelope in 1943.[30] As the family grew, they found the residence progressively cramped. On November 7th 1946 they placed an ad in the “House Sales” section of The Evening Star which read: “FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT house of cypress, plate glass and brick: radiant heat; three bedrooms, two terraces; mostly furnished; one and one-third acres landscaped near house, rest in woods; small stream; $17,000.”[31]

The Usonian home was promptly sold to Marjorie and Robert Leighey. “The day we left,” Loren Pope confessed, “I sat on the fireplace hob and wept."[32] The Leigheys moved in February 1947.

While the new owners’ adoration for Wright’s architecture never wavered, Mrs. Leighey believed the barren yard could use some work.[33] Together with a hired landscape architect – and the neighborhood children whom she paid a modest fee for gathering wildflowers – Marjorie transformed the surrounding acre into a luxurious garden.[34]

Speaking with The Washington Post in 1962, she pondered, “I think you become a better person by living here. Little by little, your pretensions fall away and you become a more truthful, a more honest person.”[35]

Because the Leigheys connected so profoundly with both the built home and sculpted land, it was an unwelcome shock when rumors began to float that “the quiet, shaded residence may be destroyed when Route 66 burrows into Virginia.”[36]

“If the new highway is to be routed through the property,” The Post reported, “the Leigheys will have to decide whether they can move the house.”[37] The situation was not only painful for the Leigheys. Though now living in Michigan, when Loren Pope heard of the “ghastly news that the urban planning vandals are about to demolish a work of art for the sake of a circumferential highway,” he immediately voiced his outrage in a letter to The Washington Post.[38]

“The Mongols astride their wild ponies never constituted the threat to Western culture that do these Mongoloids astride their slide rules and T- squares,” he fumed, echoing Frank Lloyd Wright with a grim warning: “America threatens to become the only society that ever went from infancy to decadence without a culture in between.”[39]

As if things were not fragile enough, Robert Leighey died late July 1963. “He leaves his wife, Marjorie,” the obituary read, and Marjorie was left to grapple with the fate of her home alone.[40] The prospect was daunting as, in her grief, Marjorie avoided collecting the mail she knew to contain the highway department’s letter of condemnation.[41]

It was not long before word of the threatened Wright masterpiece reached the National Park Service, National Trust for Historic Preservation, American Institute of Architects, and even Department of Interior Secretary Stewart Udall. As highway bulldozers aimed Route 66 at Marjorie’s property, the team of preservationists scrambled to devise a rescue campaign.

In March of 1964, the National Trust and AIA implored Virginia’s governor to reroute the highway, only to be told that “the state had gone too far to change its plans now.”[42] Marjorie, now being offered over $25,000 as compensation, suggested instead that she “deed her property to the National Park Service in return for a certificate designating it as a national ‘monument’ – a move that theoretically would interpose an inviolable Federal property right in the midst of Route 66.”[43]

The NPS and Interior Department tossed around the idea of picking up the house itself and moving it elsewhere, “perhaps as an exhibit of the Smithsonian Institution.”[44] Marjorie, meanwhile, had begun preparing for missionary service in Japan.[45]

Before she left, Marjorie and Secretary Udall hosted a conference with highway and conservation officials.[46] “Practicing the fine art of living room diplomacy,” Udall was driven by the conviction that America’s beauty was at stake.[47] The meeting confirmed that the highway route could no longer be altered, but optimism prevailed when officials agreed to honor Marjorie’s updated request that the house be moved.[48]

Just weeks later, the National Trust announced that it would reserve a plot for the house “at Woodlawn, the Colonial estate of Lawrence Lewis, George Washington’s nephew, near Mount Vernon.”[49] Considerable study of other nearby parklands and properties determined Woodlawn to be most appropriate due to its comparable ambience and topographical similarity to the Falls Church plot.[50] The National Trust promised Marjorie the right to occupy the residence and to honor her stipulation that the house be accessible to the public.[51]

After Mrs. Leighey and Secretary Udall signed the paperwork in July, a year since Robert’s death,[52] Marjorie left for Japan and the house left for Woodlawn. The Usonian was dismantled, moved 14 miles and reassembled at the new site by Harold Rickert, the home’s original carpenter. The ambitious operation would cost over $45,000.[53]

Still overseas in June 1965, Marjorie could not attend the joyous ceremony celebrating the Pope-Leighey house’s reconstruction at Woodlawn, but she was praised for her crucial role in its successful preservation. Secretary Udall addressed a crowd of 250 people, including the proud Loren Pope who admitted his “life-long love affair” with Wright’s work.[54]

Udall ruminated on the house’s serendipitous journey: “Now, as men and women of the centuries come to visit this historic place they may entertain thoughts of two men – George Washington and Frank Lloyd Wright – who were in quite different ways Founding Fathers.”[55]

Overshadowed by the pomp and circumstance of the day, there was even a deeper, more ideological twist at play all throughout the affair. Wolf Van Eckardt, architectural writer and critic, wrote in 1964 that the highway threat facing the Pope-Leighey house was not Frank Lloyd Wright’s first posthumous rodeo. Ironically, Wright “believed in the blessing of the automobile….He built this house so people could take advantage of the highway freedom and escape the pavements in undisturbed nature. He built it lovingly into the ground.”[56] Wright’s architecture and visions for Usonia are in fact creations for the future, Eckardt argued, explaining that its display as a “museum piece” would dishonestly make it a “relic of the past.”[57] However, he respected the rescue mission all the same, concluding with Wright’s own words that it makes the “difference between a society with a creative soul and a society with none.”[58]

Marjorie Leighey returned to her home in 1969, private resident on weekdays and host to the public on weekends, until she died in November 1983.[59] Twelve years later, the house underwent one more relocation – only a 30-foot shift this time – to stabilize its foundations and repair some of its weathered structure.[60]

Today, the Pope-Leighey House remains as true as can be to its original modest splendor, welcoming guests from near and far. Visiting the Woodlawn site was “especially meaningful” for a Falls Church local whose “parents made a point of driving us by the house in its original location” in the 1950s.[61] “We are very fortunate that the last owner of the home diligently pursued ways to save and preserve the house.”[62]

Visitors enjoy tours by the National Trust, which exhibits thought-provoking contemporary art in the Usonian home.[63] No doubt Marjorie Leighey would delight in hearing that her beloved home lives on to influence new generations.

“Little by little, your pretensions fall away and you become a more truthful, a more honest person.”[64]

Footnotes

- ^ "The Life of Frank Lloyd Wright." Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Accessed November, 2018. https://franklloydwright.org/frank-lloyd-wright/.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Reiss, Steven M. Frank Lloyd Wright's Pope-Leighey House. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014. Pg. 7

- ^ Evening Star. "Loren Pope Will Marry Miss Swart." March 29, 1939, 51.

- ^ Reiss, Steven M. Frank Lloyd Wright's Pope-Leighey House. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014. Pg. 7-8

- ^ National Building Museum. "The Pope-Leighey House: An Interview with Loren Pope." Blueprints 24, no. 3 (2006), 3-7.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Komp, Catherine. "As Frank Lloyd Wright Turns 150, A 'Small Jewel' In Virginia Shares Lessons in Simplicity." Virginia Currents, June 8, 2017. https://ideastations.org/radio/news/frank-lloyd-wright-turns-150-small-….

- ^ Reiss, Steven M. Frank Lloyd Wright's Pope-Leighey House. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014. Pg. 8

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid. pg. 9

- ^ Time. "Usonian Architect." Time, January 17, 1938.

- ^ Reggev, Kate. "What You Need to Know About Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonian Homes." Dwell. Last modified January 24, 2018. https://www.dwell.com/article/usonian-homes-frank-lloyd-wright-e75b5b56.

- ^ "Usonian." Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Accessed November, 2018. https://franklloydwright.org/style/usonian.

- ^ Reiss, Steven M. Frank Lloyd Wright's Pope-Leighey House. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014. Pg. 10

- ^ Reiss, Steven M. Frank Lloyd Wright's Pope-Leighey House. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014. Pg. 11

- ^ National Building Museum. "The Pope-Leighey House: An Interview with Loren Pope." Blueprints 24, no. 3 (2006), 3-7.

- ^ Craven, Jackie. "What Is a Usonian House? Frank Lloyd Wright's Solution for the Middle Class." ThoughtCo. Last modified July 17, 2018. https://www.thoughtco.com/usonian-style-home-frank-lloyd-wright-177787.

- ^ National Building Museum. "The Pope-Leighey House: An Interview with Loren Pope." Blueprints 24, no. 3 (2006), 3-7.

- ^ Reiss, Steven M. Frank Lloyd Wright's Pope-Leighey House. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014. Pg. 59

- ^ National Building Museum. "The Pope-Leighey House: An Interview with Loren Pope." Blueprints 24, no. 3 (2006), 3-7.

- ^ The Sunday Star (Washington, D.C.). "Falls Church Personals Of Note." March 30, 1941, 56.

- ^ National Building Museum. "The Pope-Leighey House: An Interview with Loren Pope." Blueprints 24, no. 3 (2006), 3-7.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Evening Star. "Falls Church Boy, 2, Drowns In Duck Pond." May 17, 1941, 5.

- ^ Reiss, Steven M. Frank Lloyd Wright's Pope-Leighey House. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014. Pg. 60

- ^ The Evening Star. "Suburban Sale - Virginia." November 7, 1946, 50.

- ^ Hutchinson, Carol. "College Consultant Loren Pope Commissioned a Wright House." The Washington Post, September 27, 2008, B6.

- ^ Reiss, Steven M. Frank Lloyd Wright's Pope-Leighey House. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014. Pg. 79

- ^ Ibid. pgs. 79-80

- ^ Diggins, Peter S. "Rte. 66 Perils 'Haven' on Earth." The Washington Post, October 3, 1962, C1.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Pope, Loren. "Letters to the Editor: Vandalism." The Washington Post, November 21, 1962, A16.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Washington Post. "Obituary: Robert A. Leighey." July 31, 1963, B6.

- ^ The New York Times. "House By Wright Faces Demolition; Udall Tries to Save Building From Virginia Highway." March 20, 1964.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Tuck, Lon. "Udall Acts On Wright House Fate." The Washington Post, March 21, 1964, B1.

- ^ Tuck, Lon. "Wright Living Room Diplomacy Practiced by Udall to Save House." The Washington Post, March 22, 1964, B2.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The New York Times. "Udall Drive to Save Wright House Gains." May 4, 1964, 13.

- ^ Reiss, Steven M. Frank Lloyd Wright's Pope-Leighey House. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014. Pg. 91-92

- ^ Tuck, Lon. "Udall Acts On Wright House Fate." The Washington Post, March 21, 1964, B1.

- ^ Franklin, Ben A. "A Wright House In Virginia Saved." The New York Times, July 31, 1964, 20.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Secrest, Meryle. "U-Turn Preserves House for History." The Washington Post, June 18, 1965, C2.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Von Eckardt, Wolf. "Wright Would Chuckle at the Irony." The Washington Post, March 8, 1964, G8.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Reiss, Steven M. Frank Lloyd Wright's Pope-Leighey House. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014. Pg. 111,117

- ^ "Pope-Leighey House." Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Accessed November, 2018. https://franklloydwright.org/site/pope-leighey-house/.

- ^ E, Marcy. "Two Very Different Historic Houses - Review of Woodlawn & Pope-Leighey House, Alexandria, VA." TripAdvisor. Last modified May 15, 2018. https://www.tripadvisor.com/ShowUserReviews-g30226-d536537-r580428446-W….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ "Woodlawn & Frank Lloyd Wright's Pope-Leighey House." National Trust for Historic Preservation. Accessed November, 2018. http://www.woodlawnpopeleighey.org/tours/.

- ^ Diggins, Peter S. "Rte. 66 Perils 'Haven' on Earth." The Washington Post, October 3, 1962, C1.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)