How a Maryland Crime Shaped a Presidential Election

Friday, April 3, 1987 was an unseasonably chilly, spring day in the D.C. area. With rain, and temperatures only topping out at 50, it was ideal weather to begin the weekend indoors. At 7:20 p.m., Clifford Barnes arrived at home in Fort Washington, Maryland expecting to have the house to himself. His fiancée, Angela Miller, was out with friends and wasn’t expected to return until late. However, it didn’t take Barnes long to learn — in the worst way possible — that he was not alone. An armed burglar was in his home. Barnes, at wrong end of a gun, was led to the basement and tied-up, beginning a seven hour, knife slashing ordeal.[1] Having his own fate and that of his fiancée to worry about, matters would only deteriorate further.

When Miller made it home at 2 a.m., she — like her fiancée before her — walked into a trap.[2] Taken to another part of the house by the same burglar, Miller was bound and raped. At some point during the prolonged attack, Barnes “broke free and staggered to a neighbor’s home for help.”[3] It was when the intruder went to basement to check on his first hostage that he discovered the escape. Meanwhile, Miller used the opportunity to “cut herself loose” and flee through a window.[4] After the lengthy attack the tables had turned. With two hostages gone, and police likely en route, the intruder fled the crime-scene in Barnes’ car and sped off into the early morning darkness.[5]

With descriptions of the suspect and stolen car, Prince George’s County police were already on the lookout, and located the assailant quickly.[6] After a brief chase, officers caught up to the suspect in the stolen vehicle, with one pulling alongside Barnes’s car. Aware of the perimeter forming around him, the desperate criminal responded by ramming a police car and drawing a gun. The police responded by firing on him. The culprit abandoned the car, where Kerby Hill Road meets MD 210, four miles from the scene of the crime, and ran off on foot. Suffering from gunshots to the stomach and arm, he was soon discovered hiding outside a nearby home and taken into custody. Under arrest yet still unidentified, the “three sets of identification” the man was carrying meant that there would be unraveling to do.[7] In spite of this wrinkle, it appeared that it would only be a matter of time before he would be properly identified and justice could be served.

On Wednesday, April 8 — five days after the Friday evening break-in — the offender was discharged from the hospital and sent to jail. The story quickly became more noteworthy when he was finally identified. He was William Robert Horton, who, according to The Washington Post, was “the subject of a search by Massachusetts authorities since June [1986] when he escaped from the Northeast Correctional Center.”[8] For those following the story at this early stage, it appeared as though a Massachusetts inmate escaped prison, made his way down Interstate 95 and was caught in the act of a crime spree. But this case was far more complex. Horton, who was serving a life sentence for the 1974 murder of a 17-year-old gas station attendant, wasn’t an escapee in the traditional sense of the word. Rather, he had walked out of prison on an approved weekend furlough and simply never returned.

Beginning in the 1970s, furloughs permitting incarcerated persons to leave prison as a part of their rehabilitation began to spread across the country.[9] These furlough programs were not only meant to incentivize good behavior, they also offered inmates an opportunity to visit family members, pursue employment, worship and, in many cases, prepare for a return to society.[10] In 1987, “almost 10 percent of state and federal prisoners received a furlough.”[11]

The Massachusetts furlough program dated back to 1972, when Republican governor, Francis W. Sargent, signed it into law.[12] Though all 50 states would eventually enact furlough programs for well-behaved prisoners, the Massachusetts program differed from most others in that it extended the privilege to inmates who were serving life sentences without parole. South Carolina was the only other state that followed this practice in 1987.[13]

Despite his violent record, Horton had been released for no less than nine furloughs previously. He was due back from his tenth on June 7, 1986 but, he told authorities later, was running behind schedule, after church, some shopping and a movie.[14] Instead of returning to prison late, and sullying what was up to that point a clean prison record, he decided to flee. In a 1993 interview with Jeffrey M. Elliot that appeared in The Nation, Horton claimed he used earnings from illegal gambling to afford bus fare to Washington, D.C. and while in transit, he befriended a man on his way to Florida and decided to tag along.[15] In a 2015 Marshall Project interview, Horton related a story of making it to Florida by way of buses and stolen cars.[16] After spending about a year working construction there, an unemployed and anxious Horton either moved to Baltimore to stay with friends or joined a group off travelers from Prince George’s County on their return home.[17] What is indisputable is that on April 4, 1987, Horton was arrested after he led police on a chase in Barnes’ car, which was loaded with the brutalized couples belongings.[18]

Horton would be tried and convicted of multiple counts of rape, kidnapping and attempted murder later that same year.[19] At his December 1987 sentencing, Prince George’s County Judge Vincent J. Femia intoned that Horton was a man “devoid of conscience” who “should never draw a breath of free air again.”[20] With nothing to lose, Horton requested that he be allowed to serve his time in Massachusetts. Judge Femia denied the request with a scathing indictment of Massachusetts:

“With all due respect to the citizens of our sister state, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, . . . I’m not prepared take the chance that Mr. Horton might again be furloughed or otherwise released . . . . He [Horton] now belongs to the state of Maryland."[21]

Judge Femia’s remarks would soon become fodder for the contentious 1988 presidential campaign.[22] Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis was running for president and all eyes were on the Bay State. His opponent, Vice President George H.W. Bush pushed a tough-on-crime platform as he sought remove the clouds of 1987’s Iran-Contra scandal.

While Dukakis tried to position himself as a “President for the 1990s” and touted economic growth, the Bush campaign took aim at Massachusetts’ prison furlough policy and put Horton’s crime in suburban Maryland into the spotlight.[23] The goal was clear: paint Dukakis as soft on crime. Speaking before a group of donors in Atlanta shortly before the DNC convention, Bush campaign manager Lee Atwater joked that if given the opportunity Dukakis would put “Willie Horton on the ticket.”[24]

While Clifford Barnes was publicly critical of Dukakis, the Bush campaign kept him and Angela Miller “at arms length” in order to avoid appearing exploitive.[25]Barnes pointed out that he was a registered independent and called the furlough program “a common sense issue,” and not a partisan one. He added, “If it was Bush’s furlough program that let Willie Horton go, I’d be out talking about Bush.”[25]

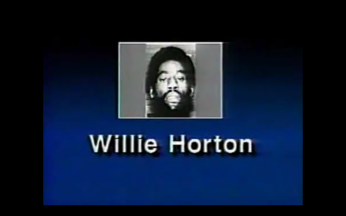

Even without directly involving the victims, the campaign sought to put Horton center stage. A series of attack ads, which fit nicely within the nascent 24-hour-new-cycle, further tied Horton’s crimes to Dukakis. In one spot, paid for by the Bush-Quayle campaign, “A Crime Quiz” leads off with the question; “Who gave weekend passes to murderers not even eligible for parole?” In another official ad, the “Dukakis furlough program” is starkly depicted as a revolving door, where furloughed inmates, leave prison only to commit more crimes “like kidnapping and rape.”[26] The most infamous of these ads, however, didn’t come from the official campaign but, rather, the National Security Political Action Committee. Instead of implicitly referring to Horton and his crimes like previous ads, this one featured Horton’s mugshot and a tally of the crimes he committed that April 1987 night in Fort Washington.[27]

William Horton – he claimed that he never went by “Willie” as had been depicted in the press – had effectively become the albatross around Dukakis’ bid to the White House and there would be no escaping. As Dukakis’ campaign manager, Susan Estrich, remarked later, the GOP had succeeded in their goal “to make Willie Horton into Dukakis’ running mate.”[28] The strategy was politically effective. On November 8, 1988 George H.W. Bush was elected President of the United States of America by a landslide.

So why was the Horton ad so effective? That’s a complicated question, but scholars have pointed to one factor above all others: race.

Even though race was not explicitly mentioned in the Horton ad, it was a big part of the messaging. As scholars Jon Hurwitz and Mark Peffley note, “While the ad could have conveyed exactly the same information without graphics, NSPAC elected to superimpose the most menacing possible picture of Horton, an African-American, over the narrative.”[29] In effect, without explicitly saying it, the ad creators were implicitly connecting race and crime – specifically African Americans and crime.

In doing so, they were resurfacing very old race-based fears, which had been proven to resonate with white voters. Indeed, stereotyping African Americans as criminals had been prevalent in American culture since the country’s inception, and had been used to justify slavery, lynching, Jim Crow, and institutionalized discrimination. As political scientist Tali Mendelberg argues:

"To understand why implicit appeals exist, why they work, and why they cease to work when they are explicit, we must understand the influence of racial stereotypes, fears, and resentments; party coalitions based on race; and the ability of a message to prime racial dispositions in white voters' minds.[30]

In effect the Horton ad was a 1980s page out of an old political playbook, which had been used time and again over the course of American history: stoking racism to shape public opinion. The implicit technique was different from earlier eras (see George Wallace’s impassioned public comments in defense of segregation in the 1960s), but the goal was the same. As University of California, Berkeley law professor Ian Haney-López noted in his study, Dog Whistle Politics, politicians in recent decades have gained success “while articulating a new vocabulary that channeled old, bigoted ideas.”[31]

Today, William Horton remains imprisoned in Maryland for his Fort Washington crimes. He has, in the years since, become a symbol of when politics speak to fear. As new attack ads are trotted out every election cycle, the name Willie Horton functions a barometer of sorts, used to determine if political campaigns have gone too far.

Footnotes

- ^ “Suspect in P.G. Rape, Torture Hospitalized After Chase.” The Washington Post, April 6, 1987, p. D4

- ^ Bidinotto, Robert James. “Getting Away With Murder.” Readers Digest,. July 1988, p. 57-63.

https://www.scribd.com/document/392182949/Getting-Away-With-Murder-by-R… - ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Suspect in P.G. Rape, Torture Hospitalized After Chase.” The Washington Post, April 6, 1987. p. D4

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Crime Watch: Southern Prince George’s County Neighborhood Report.” The Washington Post, April 9, 1987. p. 129.

- ^ “Md. Suspect Is Escapee.” The Washington Post, April 8, 1987, p. D9.

- ^ Reid, T.R. “Most States Allow Furloughs From Prison.” The Washington Post, June 24, 1988. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1988/06/24/most-states-allow-furloughs-from-prison/ad22836e-111b-4f09-aa6d-6651d2e9a04e/?utm_term=.8f64763416d1

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Bill Keller and Beth Schwartzapfel. “Willie Horton Revisited.” The Marshal Project, May 13, 2015. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/05/13/willie-horton-revisited

- ^ Duggan, Paul. “The Barneses and The Horton Debate.” The Washington Post, October 28, 1988, p. D04.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Elliot, Jeffrey M. “The Man and The Symbol: An Interview with ‘Willie’ Horton.” The Nation, August 23, 1993.

Simon, Roger. “How A Murderer And Rapist Became The Bush Campaign’s Most Valuable Player.” The Baltimore Sun, November 11, 1990.

https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1990-11-11-1990315149-story.html - ^ Ibid.

- ^ This mention of stolen cars could be a confession or it could be a way to explain stealing Clifford Barnes’ car, without confessing to the attacks.

Bill Keller and Beth Schwartzapfel. “Willie Horton Revisited.” The Marshal Project, May 13, 2015. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/05/13/willie-horton-revisited - ^ Ibid.

Elliot, Jeffrey M. “The Man and The Symbol: An Interview with ‘Willie’ Horton.” The Nation, August 23, 1993. - ^ Simon, Roger. “How A Murderer And Rapist Became The Bush Campaign’s Most Valuable Player.” The Baltimore Sun, November 11, 1990.

https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1990-11-11-1990315149-story.html - ^ Ibid.

- ^ Moss, Jonathan M. “P.G. Judge’s Prison Furlough Remarks Become Political Issue.” The Washington Post, August 18, 1988, p. MD21.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Femia who claimed in a Washington Post interview to be unaware that Dukakis was running for president in December 1987, had an autographed photo of himself with George H.W. Bush from 1982 displayed prominently in his office.

Moss, Jonathan M. “P.G. Judge’s Prison Furlough Remarks Become Political Issue.” The Washington Post, August 18, 1988, p. MD21. - ^ Seavey, Robert. “Dukakis’ ‘Peruvian Mother’ Speaks of Affectionate ‘American Son Miguel.’ ” Associated Press, October 15, 1988.

https://www.apnews.com/ae0a5b2daeeabeb52d8339b087e198d7 - ^ Edsall, Thomas B. “Race: Still a Force in Politics; GOP Stronger Among Whites in Heavily Black States.” The Washington Post, July 31, 1988. p. A 01.

- a, b Duggan, Paul. “The Barneses and The Horton Debate.” The Washington Post, October 28, 1988, p. D04.

- ^ Harrington, Rebecca. “Roger Ailes produced one of the most infamous political ads of all time…” Business Insider, May 18, 2017. https://www.businessinsider.com/roger-ailes-revolving-door-ad-bush-elec…

- ^ “This 1988 ad about convicted felon Willie Horton inspired the GOP’s latest attacked on Tim Kaine.” The Washington Post, October 3, 2016.https://www.washingtonpost.com/video/national/this-1988-ad-inspired-the-gops-latest-attack-on-tim-kaine/2016/10/03/c74931f8-8980-11e6-8cdc-4fbb1973b506_video.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.065e287144c9Horton claims to never have gone by Willie.Rodricks, Dan. “Trying to find the real Willie Horton.” The Baltimore Sun, August 12, 1993.https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1993-08-12-1993224224-story.ht…

- ^ CNN, Doug Criss. “This Is the 30-Year-Old Willie Horton Ad Everybody Is Talking about Today.” CNN. Accessed April 23, 2019. https://www.cnn.com/2018/11/01/politics/willie-horton-ad-1988-explainer-trnd/index.html.

- ^ Jon Hurwitz and Mark Peffley, “Playing The Race Card In The Post-Willie Horton Era.” Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 69, No. 1, Spring 2005, p. 99-112.

- ^ Mendelberg, Tali. “The Race Card: Campaign Strategy, Implicit Messages, and the Norm of Equality.” Princeton University Press: New Jersey, 2001, p. 7.

- ^ Haney López, Ian. “Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism & Wrecked the Middle Class.” Oxford University Press: New York, 2014, p. 16.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)