The Lynching of George Armwood

Editor’s note: Reader discretion advised. This post contains detailed descriptions of extreme violence from contemporary accounts and more recent analysis. We have elected to include these details in an effort to convey the horror of the lynch mob that murdered George Armwood because the crime and its aftermath illustrate the dynamics of racial terror that were all too prevalent in early 20th century America.

Across the Chesapeake Bay, in Princess Anne, Maryland, William Jones was constructing a pine casket for George Armwood, Maryland’s latest victim of a lynch mob. As the Baltimore Afro-American reporter Ralph Matthews noted, white onlookers, some of whom participated in the previous night’s “torture of a fellow human being,” stood by, watching.[1]

The sound of the 60-year-old’s hammer sending spikes into the makeshift box penetrated the stillness of the gathered crowd, comprised of both Black and white spectators—their silence in sharp contrast to the howling and terror of a town erupting with the “lust for the blood of a black man” only a day before.[2] Jones, “a little dark-skinned man,” thought back to his grandfather as he hammered the nails into the rickety coffin, who as a child he witnessed being sold into slavery, “never to return to his loved ones again.”[3]

Armwood’s loved ones didn’t appear on the scene that day. Neither his mother, his siblings, nor his friends were to be found. He received no burial ceremony either: “There were no tears, no psalms, no prayers” as the twenty-two-year-old’s charred and mangled body was laid inside the coffin and taken to a potter’s grave.[4] The “death-like silence” of the spectators as they looked upon Armwood’s body captured the inarticulate confrontation with the sadistic and savage core of white supremacy.[5] A silence whose repression among the white population left them complicit in upholding the violence and hierarchy of America’s racial order, and leaving the tortured task of remembrance to the brutalized Black community.

No one knew then that Armwood would be Maryland’s last recorded lynching, but in the environment of the 1930s there was little reason to suspect it would be. While the ‘30s witnessed a national decline of lynchings, rates surged in 1933, the year of Armwood’s murder, with at least 24 recorded Black lynchings.[6] Armwood’s murder also came less than two years after the lynching of Matthew Williams in Salisbury, Maryland and only a few months after an outbreak of “lynch fever” in the state.[7] Blacks on the Eastern Shore “were well acquainted with the reality of mob violence,” observed civil rights lawyer and historian Sherrilyn A. Ifill.[8]

Fallout from the Great Depression spurned resentment from many white Americans, who increasingly called on African Americans to be fired from their jobs. Mob assaults and racial violence also surged at this time, particularly in the South.[9] The increase in racial violence was both a brutally real phenomenon and a spectacle to be capitalized upon. The headline in a New York Times article called Armwood’s murder the “Wildest Lynching Orgy” in Maryland’s history.[10]

The Lynching

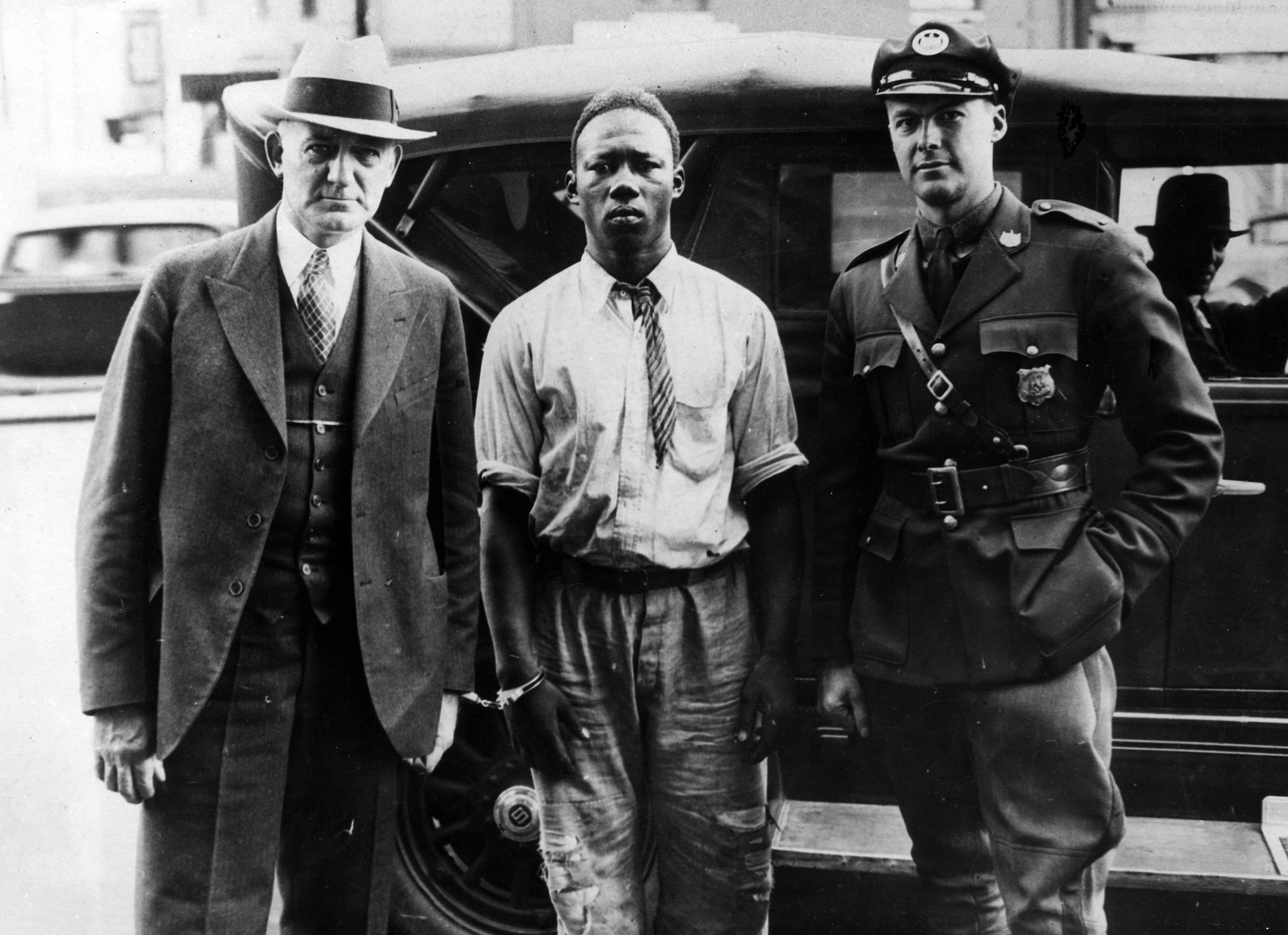

Armwood was lynched on October 18, 1933. He was accused on October 16 of attempting to assault and rape a seventy-one-year-old white woman named Mary Denston.[11] It’s believed that immediately after the alleged assault, Armwood took refuge in the home of his white employer, John Richardson.[12] Armwood was soon captured there by the police, and, according to his mother’s eyewitness testimony, was dragged out of the house and beaten so badly she thought “they would kill him” on the spot.[13] But Armwood survived, and was sent to the jailhouse in Salisbury ten miles north—placing distance between him and any potential lynch mobs in Princess Anne.[14]

To those who knew him, Armwood was “a very quiet fellow” and “a good worker.”[15] He “labored hard, never complained, and was liked by everyone who saw him.”[16] John Waters, a childhood friend of Armwood’s, added that he “was a little off at times.”[17] Armwood’s mother also claimed that his “mental condition was not the best.”[18] However, as has been noted by Sherrilyn Ifill, such claims were frequently made about lynched Black men and should be treated with some skepticism.[19]

By the time Armwood was arrested, lynch mobs were already forming in the region. Potential lynchers, driving around town in their rage to find him, even ran over and killed a 7-year-old Black girl.[20] For his own safety, Armwood was moved to a prison in Baltimore.

Almost immediately, Somerset County Judge Robert F. Duer and State Attorney John B. Robins called for Armwood’s return.[21] They were pressured by their white constituents, who, bitter over previous instances in which Black prisoners were moved to Baltimore for protection, craved vengeance.[22] Robins even promised “ample protection” for Armwood.[23] Maryland Governor Albert C. Ritchie, assured of the prisoner’s safety and warning the judge and state’s attorney that whatever happens to Armwood would be their responsibility, assented to the request.[24] On the night of the 17th, Armwood was back in Princess Anne.[25]

But Armwood’s fate was already sealed. According to one visitor, all afternoon the talk on the street was that Armwood was going to be lynched: “Everybody in Princess Anne knew it.”[26]

On the evening of the 18th, a mob assembled outside the Princess Anne jailhouse. This was the worst-case scenario for Judge Duer. Before heading off to dinner, he drove by the jail to address the crowd, telling them he was “one of them” and that he would hold them “to their honor” to avoid impeding the legal system.[27] Gov. Ritchie later stated that Duer personally called and assured him that there would be “no trouble of any kind and that it was perfectly safe to leave Armwood in Princess Anne.”[28] But the crowd spurned Duer. They stayed, and their fury grew.

By 8:30 p.m., hundreds of white men, women, and children were on the scene.[29] They taunted and assaulted the officers guarding the building. Tear gas rained down on the mob, but it wasn’t enough to prevent state police from being overwhelmed, leading to their withdrawal.[30] Using a nearby telephone pole as a makeshift battering ram, the mob broke through the jailhouse doors. They found Armwood hiding under his mattress, where he was almost immediately stabbed.[31] Then, the mob dragged him out to a howling crowd of around 2,000 spectators where he was savagely beaten.[32]

According to the Afro-American, the lynching had an “atmosphere of a bloody carnival.”[33] As Armwood was dragged down the steps of the jail, an 18-year-old came up to him and cut his ear off.[34] The mob then took Armwood all the way to a tree near Judge Duer’s house where he was hanged and tortured. One witness saw “high school girls and their boy friends parading along” the mob as he was dragged around town.[35] Afterwards, the mob dragged his body to the local courthouse, where it was doused with gasoline and burned.[36] One woman was observed telling her reluctant daughter to come “watch the N—— being barbecued.”[37] The mob then dumped Armwood’s scorched body in a nearby lumberyard, where, as scholar Andor Skotnes noted, “Black schoolchildren and adults had to pass it on their way to school and work the next morning.”[38] Mary Denston’s son, who stated he was “satisfied” with the lynching, took part of the rope that Armwood was hanged with as a “souvenir.”[39] To one Baltimorean who witnessed the lynching, the quality that stood out was the lack of drunkenness among the mob: “That crowd at Princess Anne was sober,” he said, and it howled with an indescribable noise.[40]

The Afro-American’s Clarence Mitchell captured the gory aftermath: “The skin of George Armwood was scorched and blackened while his face had suffered many blows from sharp objects and heavy instruments. A cursory glance revealed that one ear was missing and his tongue, between his clenched teeth, gave evidence of his great agony before death.”[41]

The Aftermath

In the end, none of Armwood’s attackers were ever held accountable. A grand jury hearing featured testimony from forty-two witnesses, including Black witnesses, some of whom were held in the jailhouse with Armwood on the night of his murder. All testified that they could not identify anyone involved in the lynching.[42]

When officials were able to identify suspects, the local white community rallied around them. In the weeks following the murder, the Maryland National Guard entered Salisbury to capture four suspects believed to be involved in the lynching. A riot broke out as one thousand whites from the community—who sought to protect the suspects—clashed with the Guard. After the violence cleared and the suspects were captured, a habeus corpus hearing was held the following day. The four men were cleared of any charges and released—to cheers from the white community.[43] In the end, a “conspiracy of silence” took over the town.[44]

As historian Sherrilyn Ifill remarked, Armwood’s lynching “may be the only one in the history of the United States in which nearly a dozen lynchers were identified based on the sworn affidavits of police officers, and in which four lynchers were arrested by the National Guard, and yet still no indictments were issued.”[45] The outcome was “consistent with the history of lynching investigations in Maryland. In the fourteen cases of reported lynchings in Maryland beginning in 1885 and ending in 1933, no suspected lynchers were ever indicted.”[46]

Local Reactions

After Armwood’s murder, many white residents in the Eastern Shore responded with outrage—not at the mob, but at the law. According to the Afro-American, one white resident “thought lynching was the civic duty of persons who recognized that the machinery of justice was too slow.”[47] The resident was referencing a court case involving Euel Lee, a suit in which a Black man was convicted of murder after a lengthy trial. Lee, who escaped a lynching when he was arrested in 1931,[48] was sentenced to death, but his execution was temporarily halted in October 1933 after efforts by the International Labor Defense, the legal advocacy organization of the Communist Party of the United States of America. (At the time, the ILD was also representing the Scottsboro Boys, and helped create mass publicity for the case.) Lee was executed on October 27, less than two weeks after the Armwood lynching.[49]

The Lee case and the presence of the ILD inspired many white residents to blame the communists for George Armwood’s murder.[50] Governor Ritchie was also in the crosshairs. As Salisbury minister Leonard White told the Baltimore Sun, “there would not have been a lynching” had the state had a different governor.[51] By December, especially after the battle with the National Guard, anti-Ritchie sentiment was common on the Shore—a harbinger of his political future.[52] The Crisfield Times, equivocating around the lawlessness of the mob’s action, declared that “the greatest deterrent to rape is lynching.”[53] Later, it added that while “Eastern Shoremen are not proud of a lynching,” it is “an extremely unpleasant duty that must be performed at times.”[54] In response to the Sun’s continued coverage of events following the lynching, many white Shoremen confiscated the newspaper across the region and burned them.[55]

As scholar Andor Skotnes noted, “a very large portion of the region's White community and its officials clearly supported the lynching.”[56] There were few exceptions, including one progressive white Baltimore reverend—a former Shore resident—who responded: “I feel ashamed of being an Eastern Shore man. I feel ashamed of being a white man.”[57]

But the white community wasn’t alone in their equivocation. The weight of white supremacy in the region influenced the reaction of many Blacks who faced a reasonable fear of post-lynching violence and intimidation. In December, three Black leaders on the Shore released a shocking statement that placed full responsibility for the lynching on ILD lawyer Bernard Ades, attorney for Euel Lee.[58] The authors, Rev. James. M. Dickerson, former schoolteacher James L. Johnson, and mortician James F. Stewart, denounced Ades “and his ilk,” who they charged with spreading “Communist propaganda” from Russia. The group also blamed Ades’ “tactics” for the lynching of Matthew Williams. (The Salisbury Times, where the Black leaders’ statement was published, refused to cover the Williams lynching in 1931.)[59] The statement also distorted race-relations on the Eastern Shore: “We enjoy the lives we live here on this beautiful Shore, graced by nature and abounding in plenty. We feel that our people here, on the average are more intelligent, more understanding, more prosperous, more industrious and happier than are our people in any other section of this nation.”

Others saw through the statement’s pandering to the white community. The Afro-American denounced the authors as the “Three Uncle Jameses.”[60] It added: “The Lynching Shore has sunk pretty low when it can get any colored person to issue such a left-handed glorification of murderers.”[61] Nineteen Black leaders on the Shore issued their own public denunciation, asserting that Dickerson, Johnson and Stewart “do not and cannot speak for anyone but themselves and those to whose paper the saw fit to affix their names.”[62] They also noted the underlying fear-ridden motivation: “the ‘statement’ bears all the ear marks of a command to ‘sign on the dotted line,’ by some interest which would profit most by impressing the public that the Negro on the Eastern Shore is spineless.”

The response marked a shift in Black resistance to white supremacy in the region. “They refused to acquiesce in efforts to shift responsibility for the lynchings away from Eastern Shore whites,” wrote Sherrilyn Ifill.[63] Moreover, Ifill added, by making their reply public, they offered an “unequivocal alternative account of a black response to the lynchings.”

The Black Freedom Movement is Energized

Armwood’s murder inspired a new wave of anti-lynching activism and demonstration in Baltimore, largely from center-left organizations.[64] The most active included the Baltimore Urban League, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Socialist Party of Maryland, the ILD, and other communist-affiliated groups.

Among the many actions taken, the BUL and the NAACP, along with almost 30 other interracial organizations, led a delegation to push Gov. Ritchie for a state anti-lynching bill.[65] The NAACP, whose Baltimore branch was by 1933 in decay, experienced a revival after Armwood’s lynching. It called on President Franklin Roosevelt to speak out against the lynching and drafted a new federal anti-lynching bill.[66] The Socialist Party called for Ritchie’s impeachment and the prosecution of both Duer and Robins.[67] The Afro-American helped instigate the creation of an interracial committee that denounced the governor and called on the removal of all Somerset County officials.[68]

While justice failed to arrive for Armwood, Gov. Ritchie’s handling of the lynching contributed to the end of his political career, and Judge Duer lost his re-election bid in 1934.[69] The demonstrations of local anti-lynching organizations also helped strengthen the national anti-lynching cause and bolstered Baltimore’s Black freedom movement.[70]

Reflections and Reconciliation

Almost a year after George Armwood was killed, Clarence Mitchell of the Afro-American visited Princess Anne. He found it much the same: “that is—a low element of ne’er-do-well ruffians still believe in going about looking for trouble and have a nasty habit of finding it among the colored people.”[71] While he called the town “the devil,” he held out hope that it could become “a sensible, thriving, and law abiding place just as soon as it chases the main hoodlums out.”

Nearly a century later, the specter of racial violence remains within the living memory of hundreds of Maryland residents.[72] If any racial reconciliation process is to occur, as Sherrilyn Ifill has argued, it is “vital” for a white community to confront its history of racial violence.[73]

Such efforts have grown in recent years. In 2019, Governor Larry Hogan signed into law House Bill 307, which launched the Maryland Lynching Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The commission is dedicated to investigating racially motivated lynchings in the state and holding public meetings at sites where lynchings were documented.[74] The commission, the first in America to research lynchings, held its first public hearing in October 2021 in Allegany County.[75]

“In the United States and in Maryland, they really don’t want us to know or talk about our negative history,” Tina Johnson, a distant cousin of George Armwood, told the Baltimore Sun in 2018. “I want to know all my history, whether it’s good, bad, or indifferent.”[76]

Footnotes

- ^ Ralph Matthews, “Potter’s Field Gets Last Remains of Mob Victim,” Afro-American, October 28, 1933.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid. Accounts of Armwood’s age varies. The age here comes from his mother’s testimony, Andor Skotnes, A New Deal for All?: Race and Class Struggles in Depression-Era Baltimore (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 119, 332.

- ^ Matthews, “Potter’s Field.”

- ^ “History of Lynching in America,” National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, last modified December 3, 2021, https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/history-lynching-ame…; Charles Seguin and David Rigby, “National Crimes: A New National Data Set of Lynchings in the United States, 1883 to 1941,” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 5, no. 1-9 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023119841780; “Lynchings Stats Year Dates Causes,” Tuskegee University Archives, accessed January 20, 2022, http://archive.tuskegee.edu/repository/digital-collection/lynching-info….

- ^ Skotnes, A New Deal for All?, 120.

- ^ Sherrilyn A. Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the 21st Century (Boston, Beacon Press, 2018), 29-30.

- ^ “Race Relations in the 1930s and 40s,” Library of Congress, accessed January 20, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-s…; Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 29.

- ^ “Maryland Witnesses Wildest Lynching Orgy in History,” New York Times, October 19, 1933.

- ^ “George Armwood (b. 1911 – d. 1933),” Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series), MSA SC 3520-13750, https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/013700/0137….

- ^ Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 34-35.

- ^ Levi Jolley, “Mother’s Heart is Broken from Lynch Tragedy,” Afro-American, October 28, 1933.

- ^ “George Armwood (b. 1911 – d. 1933),”; Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 36.

- ^ Levi Jolley, “Armwood Quit School in 5th Grade, Says Pal,” Afro-American, October 28, 1933.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Jolley, “Mother’s Heart is Broken.”

- ^ Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 34.

- ^ Levi Jolley, “Child is Killed as Mob Seeks Prey to Lynch,” Afro-American, October 28, 1933. Princess Anne officials “refused to conduct a hearing in the matter” of the automobile accident, ibid.

- ^ “George Armwood (b. 1911 – d. 1933).”

- ^ Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 36.

- ^ “Somerset Jury will be Recalled for Trial of Man on Assault Charge,” Salisbury Times, October 17, 1933.

- ^ Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 39.

- ^ “Police Squads Escort Negro Back to Shore,” Baltimore Sun, October 18, 1933; “Governor Puts Responsibility on Duer and State’s Attorney,” Baltimore Sun, October 19, 1933.

- ^ John Louis Clarke, “Robins and Daugherty Told Armwood Would be Lynched,” Afro-American, October 28, 1933.

- ^ Quoted in Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 39.

- ^ “Governor Puts Responsibility.”

- ^ Skotnes, A New Deal for All?, 122; Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 38-40.

- ^ Skotnes, A New Deal for All?, 122.

- ^ Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 39-40.

- ^ Skotnes, A New Deal for All?, 122; Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 40; “Roman Holiday as Armwood is Hanged, Burned,” Afro-American, October 28, 1933.

- ^ “Roman Holiday.”

- ^ Clarke, “Robins and Daugherty.”

- ^ “Sober Men Yelled Like Beasts at Lynching, Says a Witness,” Baltimore Sun, October 20, 1933.

- ^ Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 40.

- ^ “Roman Holiday.”

- ^ Skotnes, A New Deal for All?, 122.

- ^ “Glad They Lynched Him, Says Son of Alleged Victim,” Afro-American, October 28, 1933. Many “curiosity seekers” also sought souvenirs after the lynching, “Town Flooded with Curiosity Seekers,” Afro-American, October 28, 1933.

- ^ “Sober Men Yelled Like Beasts.”

- ^ Clarence Mitchell, “Mob Members Knew Prey was Feeble-Minded,” Afro-American, October 28, 1933.

- ^ “George Armwood (b. 1911 – d. 1933).”

- ^ Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 68.

- ^ “Conspiracy of Silence in Md. Lynching Orgy,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 28, 1933.

- ^ Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 92.

- ^ Ibid., 56.

- ^ Clarence Mitchell, “Observations and Reflections,” Afro-American, October 28, 1933.

- ^ "Move Suspect in Axe Killing," Afro-American, October 17, 1931.

- ^ “Appeal to Roosevelt Fails to Save Slayer,” New York Times, October 27, 1933.

- ^ John G. Alexander, letter to editor, Marylander and Herald, October 28, 1933; Skotnes, A New Deal for All?, 123.

- ^ “Shore Cleric Puts Lynching Onus on Ritchie,” Baltimore Sun, December 8, 1933.

- ^ “How Shore Feels Toward Ritchie,” Marylander and Herald, December 8, 1933.

- ^ “The Lynching of Armwood,” Crisfield Times, October 20, 1933.

- ^ “The Armwood Lynching,” Crisfield Times, October 27, 1933.

- ^ “Sunpapers are Unpopular Here,” Marylander and Herald, December 1, 1933.

- ^ Skotnes, A New Deal for All?, 123.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Colored People of Salisbury Protest Interference of Ades,” Salisbury Times, December 6, 1933; “Colored People Blame Communists and Ades,” Marylander and Herald, December 8, 1933.

- ^ Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 71.

- ^ “Three Uncle Jameses Speak,” Afro-American, December 16, 1933.

- ^ “The Three Jimmies Glorify Lynching,” Afro-American, December 16, 1933.

- ^ “Salisbury, Md., Citizens Hit the Three Jameses,” Afro-American, December 16, 1933.

- ^ Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 73.

- ^ “The Press on Maryland’s Second Annual Lynching,” Afro-American, October 28, 1933.

- ^ Skotnes, A New Deal for All?, 125-126.

- ^ “N.A.A.C.P Asks the President to Speak Out,” Afro-American, October 28, 1933; NAACP Drafts Anti-Lynch Legislation,” Afro-American, November 4, 1933; Skotnes, A New Deal for All?, 120-121.

- ^ Ibid., 124-125.

- ^ “Interracial Group Raps Governor,” Afro-American, October 28, 1933.

- ^ Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 26, 103.

- ^ Skotnes, A New Deal for All?, 138-139.

- ^ Clarence Mitchell, “Observations and Reflections,” Afro-American, September 22, 1934.

- ^ Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn, 21.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Home,” Maryland Lynching Truth and Reconciliation Commission, accessed February 1, 2022, https://msa.maryland.gov/lynching-truth-reconciliation/index.html.

- ^ Teresa McMinn, “Nation’s First Lynching Truth and Reconciliation Commission to Hold First Public Hearing in Allegany County,” Cumberland Times-News, September 26, 2021, https://www.times-news.com/news/local_news/nation-s-first-lynching-trut….

- ^ Jonathan M. Pitts, “Bringing a Dark Chapter to Light: Maryland Confronts its Lynching Legacy,” Baltimore Sun, September 25, 2018, https://www.baltimoresun.com/maryland/bs-md-lynching-in-maryland-201809….

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)