The Deal Done in the Dark

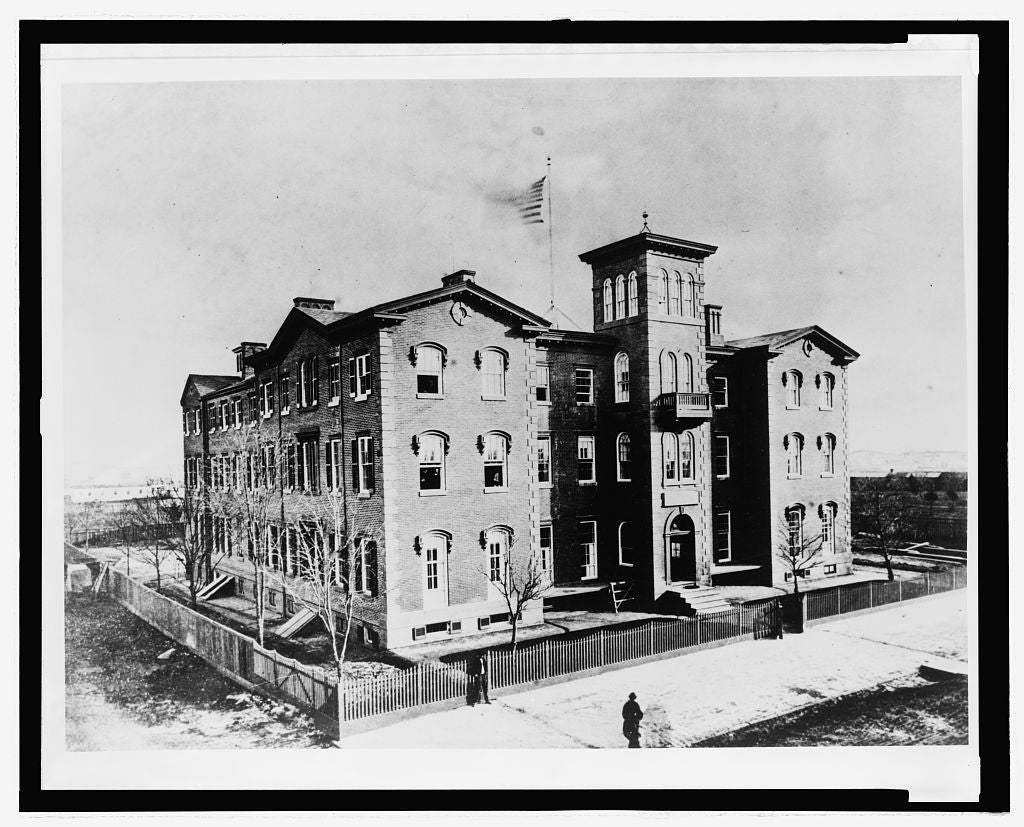

In 1866, the Washington City Orphan Asylum was not a place of childhood care, as its name suggests.

Instead, it was a place of diplomacy and treaty-signing.

Situated on the corner of 14th and S streets NW, the three-story brick structure had been erected upon the grounds of an old cemetery. It was described as cramped, “suburban in character,”[1] and not quite meeting fire safety protocols (it almost burned down twice). But from late 1866 to mid-1875, this was the location of the Department of State.

In the years following the Civil War, State Department employees were forced out of their old offices in the Northeast Executive Building because an extension to the Treasury Department was being constructed on that site. As a result, the nearly-completed Orphan Asylum was temporarily rented to the government.[2] Though the move was less than ideal, the walls of the new State Department would soon see major historical and diplomatic events unfold.

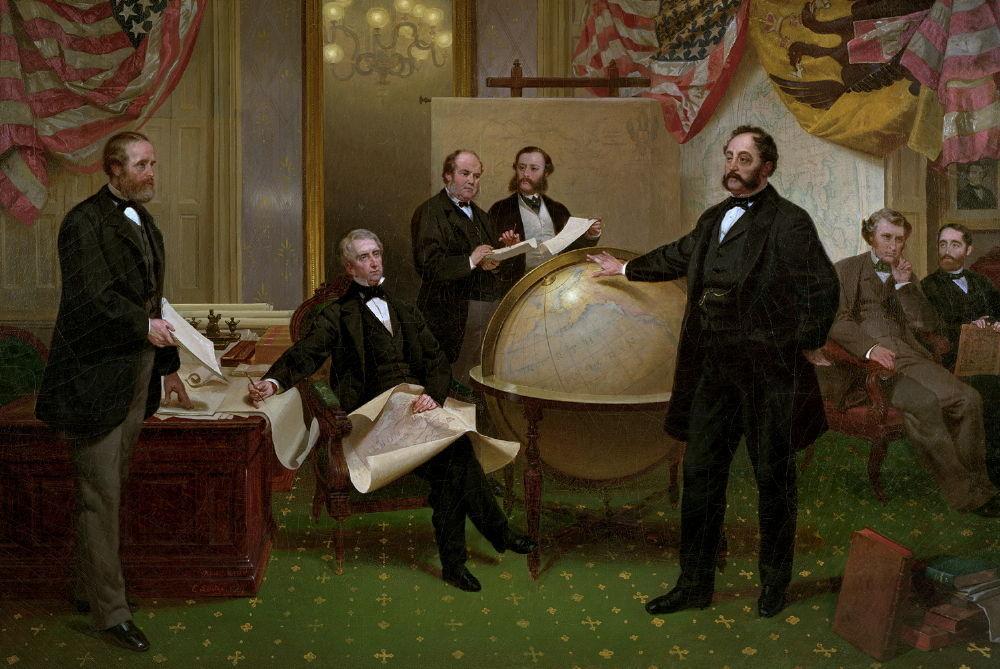

Emanuel Leutze’s painting “Signing of the Alaska Treaty” famously depicts one particularly remarkable occasion from 1867: a group of men gather in a room in the State Department, lamp light glowing in the latest hours of the evening, maps and flags strewn about the space. Most prominently, Russian Ambassador Baron de Stoeckl stands before a globe, his hand hovering over the Russian-American lands he is looking to sell; and Secretary of State William Henry Seward sits before him, listening intently.[3]

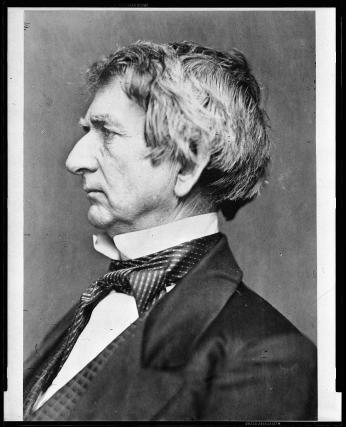

Seven years earlier, William Seward had spoken to a crowd in St. Paul, Minnesota. He was short, his stature awkward, his shockingly red hair slightly tousled. But his words were bold, and he was seeking the Republican nomination for the 1860 presidential race.

During this September 1860 campaign speech, Seward spoke of the Russian-American territory that was gradually establishing in the northwest region of the continent, asserting:

“Go on, and build up your outposts all along the coast, up even to the Arctic ocean; they will yet become the outposts of my own country—monuments of the civilization of the United States in the North-west!”[4]

But for the next seven years, Seward’s dream of acquiring Russian America was paused. Though he did not win the presidency in 1860, Seward still found himself moving to Washington, D.C.; upon Lincoln’s election, he became his secretary of state, living right across the street from the White House in Lafayette Square. The ensuing Civil War would be Seward’s primary concern for the time being.

After the tumultuous events of the war, and following Lincoln’s untimely death, Andrew Johnson became president in 1865. He kept Seward on as secretary of state and offered him the opportunity to, once again, look toward the lands in the great northwest.

Seward always hoped that America would expand widely into the West. The Alaska territory particularly interested Seward; where many saw barren, unprofitable waste lands, Seward saw a wealth of natural resources, an opportunity to trade with East Asia, and the possibility to later acquire British Columbia.

When the moment came to jump into negotiations with Russia about the territory, then, Seward did exactly that. He befriended Eduard de Stoeckl, Russian Ambassador to the United States. Seward peaked his interest in making a sale to America, convincing him that this land was the key to amicable relations between the two countries. Word went back and forth between Russia and the United States, Stoeckl and Seward. They developed draft after draft of a treaty, whereby Russia would sell its property for roughly $7 million in gold. By the last days of March in 1867, all that was left to do was await permission from the Russian emperor to go through with the sale.[5]

Late in the evening on March 29, Seward was sitting in the library of his Lafayette Square home, enjoying a pleasant Friday night with his family. They were playing a game of whist when a knock came at the front door.

Stoeckl was soon brought into the room. He announced, “I have a dispatch, Mr. Seward.”

Seward looked up from his game. Stoeckl continued, stating that he had received word of the emperor’s consent to the sale. Realizing that it was nearly ten o’clock in the evening, however, he offered to meet Seward at the State Department the following day, so that they could finish and sign the treaty.

The secretary of state merely smiled, and replied:

“Why wait till tomorrow, Mr. Stoeckl? Let us make the treaty tonight.”

“But your department is closed,” said Stoeckl. “You have no clerks, and my secretaries are scattered about the town.”

“Never mind that… if you can muster your legation together before midnight, you will find me awaiting you at the department, which will be open and ready for business.”[6]

Just five months after moving his department into the new space, Seward conducted the purchase of Alaska in the small rooms of the orphanage-turned-State Department. Surrounded by hundreds of books still settling into their shelves, and hallways full of empty offices,[7] the men negotiated; as Seward’s son, Frederick, recalled, “Light was streaming out of the windows of the Department of State, and apparently business was going on there as at mid-day.”[8] From midnight until four o’clock in the morning, Seward, Stoeckl, and their select colleagues negotiated the sale of a land far outside their odd spot in Washington. Finally, they signed the treaty in the early hours of March 30, 1867.[9]

Seward’s decision to conduct the purchase of Alaska in the middle of the night is, though intriguing, not entirely surprising. The secretary of state was clever, and he knew that this timing was close to perfect: the Senate would be ending its session at noon on March 30, and Seward hoped that if he presented a completed treaty to the Senate that morning, they might approve it. Unfortunately, the Senate insisted that they needed more time to consider the treaty, so a special session would start two days later for that to happen.[10]

At the moment the treaty was signed on March 30, though, few people outside the room of the State Department knew of the negotiations between Russia and America. Seward hoped to keep outsiders from learning about the purchase while it was still in the works; he believed that false press reports might be released before he and Stoeckl had even agreed upon the purchase’s terms.[11]

That said, news did eventually come out about the purchase. As Seward appealed to various members of the Senate and Congress in the coming days, hoping to win them over so that the treaty could be officially ratified (which it was on April 9, 1867),[12] word of the purchase reached American citizens via newspapers—and there was a mix of reactions to the event.

Most press responses were positive. One article, published in Washington’s Evening Star, shared a testimony from a person who had recently visited Russian America: “…its value is greater than has been supposed. The rejection of the treaty would cause great dissatisfaction on [the West] coast…. fisheries and timber may be very valuable.”[13] Similarly, a New York Times article praised the resources available in the land, detailing its various minerals, sources of timber, and climate, concluding that “upon the whole, Russian-America … is a valuable country in itself, viewed intrinsically.”[14]

On the other hand, however, the occasional newspaper responded negatively to the Alaska purchase. Attempting to express that the territory had no true worth and was purchased under suspicious and unethical circumstances, the New York Tribune described the purchase as “folly”: “There is not, in the history of diplomacy, such insensate folly as this treaty.”[15]

Over a century later, the term “Seward’s folly” has persisted as a moniker for the Alaska purchase. This is peculiar, considering that today, few would argue with the idea that the purchase of Alaska turned out to be an incredible investment for the United States.[16] So why did this nickname prevail? Though difficult to say, maybe it is a reference to the secrecy of the event, and the resulting uncertainty some individuals felt about the decision. Indeed, backroom deals in the cover of darkness are often viewed with a healthy level of skepticism.[17]

But ultimately, the purchase of Alaska was worthwhile, despite 19th century views of the matter—and Seward had known it all along. After retirement, when asked what he believed his most significant accomplishment as secretary of state had been, Seward allegedly replied:

“[The Alaska purchase]… but it will take the country a generation to appreciate it.”[18]

Footnotes

- ^ John Clagett Proctor, "Distinguished Woman Served Orphan Asylum in Century and a Quarter," Evening Star (Washington, DC), November 24, 1940, 40.

- ^ United States Department of State, "Washington City Orphan Asylum: November 1866-July 1875," Office of the Historian, https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/buildings/section26.

- ^ Emanuel Leutze, Signing of the Alaska Treaty, 1867, illustration, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alaska_purchase.jpg. The painting now hangs in the Seward House Museum in Auburn, NY.

- ^ Frederick W. Seward, Seward at Washington (New York: Derby and Miller, 1891), 346.

- ^ Walter Stahr, Seward: Lincoln's Indispensable Man (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012), 482-484.

- ^ Seward, Seward at Washington, 348.

- ^ "The New State Department Building," The Evening Star (Washington, DC), November 19, 1866, 2.

- ^ Seward, Seward at Washington, 348.

- ^ The title of this post, “The Deal Done in the Dark,” comes from a phrase coined over time by staff and interpreters at the Seward House Museum in Auburn, NY, referring to the Alaska purchase as having been completed a) in the dark of night, b) without Seward having ever actually visited Alaska, and c) with much of the U.S. public and government “in the dark” about the purchase at the time it was completed.

- ^ Stahr, Seward: Lincoln's, 486-487.

- ^ Stahr, Seward: Lincoln's, 484.

- ^ "The Russian Treaty," The Evening Star (Washington, DC), April 10, 1867, 2.

- ^ "The Russian-American Treaty," The Evening Star (Washington, DC), April 6, 1867, 2.

- ^ "Letter from Mr. Collins to Secretary Seward," The New York Times (New York), April 9, 1867.

- ^ "The Russian Treaty," New York Tribune (New York), April 9, 1867, 1.

- ^ The Seward House Museum in Auburn, NY commemorates Seward’s story and his purchase of Alaska. Recently, the Museum celebrated the 150th anniversary of the purchase with the unveiling of a statue.

- ^ The public was not entirely wrong to be concerned about the secrecy of the treaty; in fact, it seems that Seward, himself, was engaged in, or at least aware of, some questionable financial actions surrounding the purchase. On at least two separate occasions in casual conversation, Seward referred to possible bribes that Stoeckl had paid in exchange for support of the treaty by newspaper editors and politicians. See: Stahr, Seward: Lincoln's, 517-518.

- ^ John M. Taylor, William Henry Seward: Lincoln's Right Hand (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 1996).

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)