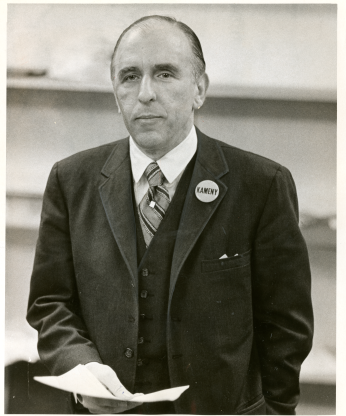

Fired for Being Gay, Frank Kameny Spent the Rest of His Life Fighting Back

By the late 1960s, Frank Kameny was receiving regular letters from men and women around the country, all employed in the federal civil service or the United States military. They wrote to him seeking help after having been interrogated or fired, denied a security clearance or threatened with dishonorable discharge. Why? Because they were gay. Kameny, as president of the Mattachine Society of Washington, an early gay rights organization, fielded letters, offered advice and helped workers appeal their dismissals or mount a legal challenge.

“I hope you can help me,” one Marine Corps private wrote in early 1969, “I told my commanding officer that I am gay.”[1]

Threatened with a dishonorable discharge and even time in the brig, the man wrote to the Mattachine Society seeking help, not wanting to face discipline for "being the way I am."[2]

Kameny would spend months corresponding with this man and his superiors trying to fight the dishonorable discharge. For Kameny, it was personal. In 1957, he lost his job as a civil servant thanks to a policy that justified firing employees for “sexual perversion,” which encompassed homosexuality.[3] The government, however, surely had no idea that firing Kameny would take a Harvard-educated astronomer and turn him into one of the early, unrelenting leaders in the fight for gay rights.

In 1950, Kameny was pursuing a doctorate degree in astronomy at Harvard. Meanwhile, in Congress, a Senator from Wisconsin was making waves with accusations about subversives in the State Department. Most are familiar with the Red Scare—Joseph McCarthy’s crusade against communists in the State Department. But what has been largely missing from history textbooks is the story of the Lavender Scare, an effort spanning three decades to rid the federal government of homosexuals.[4] David K. Johnson, a historian, has written the definitive history of the Lavender Scare, chronicling its origins and it impacts.

Motivated by the same post-war anxieties as the Red Scare, McCarthy and other U.S. officials claimed that homosexuals were “security risks” because foreign governments could use their sexual orientation as blackmail.[5] Officials saw homosexuality as a psychological defect and used phrases like sex perverts and sexual deviants to label their crusade against gays in the federal government.

McCarthy, in his 1950 Wheeling West Virginia speech, famously claimed to have evidence of 205 card-carrying communists in the State Department. When pressed for evidence in Congress, he testified for hours and noted specific cases, including two that involved gay men.[6]

In defense of the State Department, the head of its security program, John Peurifoy, denied there were communists at the agency, but he announced that State had fired some 200 employees deemed “security risks,” 91 of whom were gay.[7] The Peurifoy revelation set off a frenzy of media coverage, calls for Congressional investigation and public fear about slipping morals in the United States. It brought the Lavender Scare out into the open, but anti-gay purges in the State Department had in fact begun, quietly, years earlier. In the late 1940s, the State Department adopted a new policy for screening loyalty and security risks, which classified a series of behaviors, including homosexuality, as grounds for dismissal.[8]

The Lavender Scare sparked multiple Congressional investigations, and though McCarthy’s prominence would be short-lived, the impacts of the scandal would continue for years. In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower signed an executive order that barred homosexuals from working for the government or government contractors.[9] Johnson estimates between 5,000 and 10,000 people were fired or resigned during the Lavender Scare.

The Lavender Scare was, in part, a reaction to the growing gay subculture in D.C. and the relative acceptance members of this community enjoyed in the nation’s capital.[10] Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, young people flocked to Washington to work for one of the New Deal agencies or to support the war effort—among them gay and lesbian Americans.

Historians suggest the reason that many of us know so little about the Lavender Scare is because, when these workers lost their jobs, they tried to keep the basis of their firings a secret. Staffers confronted with allegations often chose to resign and avoid publicity, which meant the Lavender Scare was a largely faceless scandal. While the situation generated press coverage at the height of the McCarthy era, it later slipped from the headlines. And unlike the blockbuster hearings of accused communists like Alger Hiss, purges of gay and lesbian workers continued for a decade in drab interrogation rooms before anyone vocally challenged the practice.

Everything changed with Frank Kameny, a World War II veteran with a Ph.D. from Harvard, who lost his government job because he was gay.

Kameny moved to D.C. for a teaching post at Georgetown University in the mid-1950s, but after a year, he left to work as an astronomer for the Army Map Service. Only five months into the job, Kameny was on assignment in Hawaii when he got word that he should return to Washington immediately.[11] It was late 1957, and investigators from the Civil Service Commission brought him into an interrogation room to question him about a California arrest record from 1955. In August of that year, Kameny was arrested in a known “gay cruising area” and charged with lewd and indecent conduct.[12]

The agency accused him of falsifying a government form by misrepresenting the arrest when he applied for the AMS position. Investigators asked Kameny the same question they asked countless workers in the same position: “Information has come to the attention of the U.S. Civil Service Commission that you are a homosexual. What comment do you care to make?”[13]

Kameny argued he couldn’t give an intelligent reply without knowing precisely what information the CSC had about his sexuality. He refused to answer further questions, stating that his private life was “not the proper concern of the CSC or of the US Government.”[14]

Kameny lost his job, and the Civil Service Commission disqualified him from federal employment for three years, on the grounds of his “immoral conduct.” But unlike so many of the gay men and women dismissed throughout the preceding decades, Kameny was not willing to let things lie. He appealed his firing to the Army Map Service and the Civil Service Commission. Both were denied.

Throughout the appeals process, Kameny was rankled by the government’s refusal to give him any information about the “immoral” acts he allegedly committed, beyond the arrest record. He balked at the CSC’s assertion that he was given an opportunity to explain himself, suggesting in his appeal that “it is impossible to give explanations when one is not informed of what one is to explain.”[15]

In the appeals, Kameny emphasized the skillset he brought to the Army Map Service—astronomers were needed and he was good at his job. It wouldn’t benefit the government to see him dismissed, he wrote.[16]

The New York-born scientist never envisioned himself becoming an activist. He had grown up in Queens obsessed with stars and came of age in time for the space race, when good astronomers were in high demand. In fact, when Kameny began searching for a new job, he discovered he was “in excessively great demand.”[17] A number of companies were willing to “woo” him, but the plans always derailed when “the security question came up each time.”[18] Unable to work, Kameny was forced to rely on unemployment insurance and donations. There was an eight-month period where he got by on 20 to 25 cents per day. It was a treat, he later recalled, when he could afford the extra five cents to put a pad of butter on his mashed potatoes.[19]

“I was determined that while I would compromise up to a point on the type of work I would do,” Kameny wrote in 1960, “I was NOT going to throw away my training and abilities on some menial job, even if I starved first – and I almost did.”[20] Left with few options, Kameny decided his next step would be to challenge the federal government in a way no one ever had before. For the first time, somebody would ask the courts to recognize discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

In lower court filings, Kameny relied on a logic that distanced himself from the charges of homosexuality, and according to Johnson, argued he should “be examined as an individual.”[21] The courts sided with the government, and Kameny’s lawyer abandoned the case as hopeless.[22] So, despite having no legal training himself, Kameny in 1960 wrote his own pro se[23] petition asking the Supreme Court to hear his case.

His arguments grew bolder, and the brief took a revolutionary stand for the time. Kameny said the government was treating an entire group of Americans like second-class citizens. He framed the anti-gay discrimination as an issue of civil rights, the same as discrimination based on race or religion:

In World War II, petitioner did not hesitate to fight the Germans, with bullets, in order to help preserve his rights and freedoms and liberties, and those of others. In 1960, it is ironically necessary that he fight the Americans, with words, in order to preserve, against a tyrannical government, some of those same rights, freedoms and liberties, for himself and others.[24]

Kameny argued the government had no right to determine what is or is not “moral.” But, well beyond that, he asserted “flatly, unequivocally, and absolutely uncompromisingly, that homosexuality, whether by mere inclination or by overt act, is not only not immoral, but … for those choosing voluntarily to engage in homosexual acts, such acts are moral in a real and positive sense, and are good, right, and desirable, socially and personally.”[25] (Emphasis added)

Kameny’s story, however, didn’t end with a triumphant Supreme Court victory, some landmark decision that altered U.S. policy. The Court declined to hear his case, and change would come slowly for the gay community. After the rejection, Kameny co-founded the Mattachine Society of Washington and used this platform to advocate for gay rights. The society led the first public protest for gay rights outside the White House in 1965—years before the riots at the Stonewall Inn in New York. Kameny participated in pickets outside other D.C. buildings, like the Pentagon, and an annual protest at Independence Hall in Philadelphia. It was a new, more militant style of advocacy for the gay community, and Kameny even faced internal resistance to these tactics among members of the Mattachine Society.

Some of the picket signs they carried outside the White House read, “Sexual preference is irrelevant to employment,” and “First class citizenship for homosexuals.” Kameny’s stated, “We want: federal honorable discharge, security clearances, conferences with our govt officials.”[26] Federal employees had a new ally in Kameny who helped numerous people challenge their firings, fight for a security clearance or shepherd a case through the courts. He offered guidance, served as personal counsel or connected those in need with an ACLU attorney.

When Kameny took on someone’s case, he would sometimes warn the client’s supervisors that he wouldn’t be afraid to generate publicity. He wrote letters to officials deriding anti-gay discrimination in the strongest terms, at a time when other members of the gay community were reluctant to use their real names in public.

It was a radical approach that forced the government to defend the logic behind its discriminatory policies.

By the late 1960s, the courts were beginning to question the status quo. The judicial system would hand down small victories, starting with Clifford Norton, a NASA employee fired for immoral conduct. The court ruled in his favor, stating the government had not demonstrated any link between Norton’s private behavior and his job performance.[27] It created a new standard which meant homosexuality alone was no longer grounds for dismissal.

It took until 1975 but the civil service commission—today called the Office of Personnel Management—reversed its policy on gay and lesbian employees. As one man who Kameny had counseled wrote to him that year, it was a good sign that government agencies were beginning to “drop their ludicrous harassment of homosexuals, allowing us to do the jobs we can so well do.”[28]

For Frank Kameny, the new policy was a victory in a fight he did not seek out, but refused to run from. Recalling his firing in 1989, the astronomer-turned-activist said he felt it “was a declaration of war against me by my government.” But, he continued, “A, I don’t grant my government the right to declare war against me. And B, I tend not to lose my wars.”[29]

The U.S. government eventually acknowledged as much. In the 1990s, President Bill Clinton signed an order prohibiting the denial of a security clearance based on sexual orientation. In 2009, John Berry, the first openly gay director of the OPM, issued an apology to Kameny for his firing.

Footnotes

- ^ Letter to Frank Kameny, January 1969, Kameny, Frank, and Mattachine Society Of Washington. Frank Kameny papers. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://lccn.loc.gov/mm2006085340.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ U.S. President. Executive Order. “Security Requirements for Government Employment, Executive Order 10450 of April 27, 1953.” Federal Register 2489, 3 CFR, 1949-1953 Comp., p. 936: https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/…

- ^ Johnson, David K. The Lavender Scare. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2004. Print.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ U.S. President. Executive Order. “Security Requirements for Government Employment, Executive Order 10450 of April 27, 1953.” Federal Register 2489, 3 CFR, 1949-1953 Comp., p. 936: https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/…

- ^ Johnson.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Kameny, Frank, and Mattachine Society Of Washington. Frank Kameny papers. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://lccn.loc.gov/mm2006085340.

- ^ Frank Kameny to the United States Civil Service Commission, “Sworn appeal by Dr. Franklin E. Kameny to decision received from the Civil Service Commission on January 18, 1958.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Letter from Frank Kameny to the Mattachine Society, Inc., “Letter from Frank Kameny to the Mattachine Society Inc.,” May 5, 1960, Frank Kameny and Mattachine Society Of Washington. Frank Kameny papers. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://lccn.loc.gov/mm2006085340.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Marcus, Eric. “Episode 05 - Frank Kameny.” Making Gay History, Making Gay History, 17 Apr. 2019, makinggayhistory.com/podcast/episode-1-5/.

- ^ Letter from Frank Kameny to the Mattachine Society, Inc.

- ^ Johnson.

- ^ Mills, Donia and Phil Gailey, “Kameny’s Long Ordeal Personifies Wider Gay Struggle.” The Washington Evening Star, 10 April 1981: p. A8

- ^ Pro se meaning for oneself

- ^ Franklin Edward Kameny v. William Brucker, Secretary of the Army, et al., Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, no. 676, U.S. Supreme Court, October 1960 term

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Marcus, Eric. “Episode 05 - Frank Kameny.”

- ^ Johnson.

- ^ Letter to Frank Kameny, August 18, 1975, Frank Kameny and Mattachine Society Of Washington. Frank Kameny papers.

- ^ Marcus, Eric. “Episode 05 - Frank Kameny.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)