Can WWE Trace Its Roots to a Small Garage in Washington D.C.?

One cold night, on the corner of 14th and W Street, NW, a small garage became the scene of a bloody brawl:

“Nagurski started very briskly about the business of bumping off the city’s No. 1 ranking villain, bowling him over with three vicious flying tackles. Chewacki…retaliated with his usual strangle-hold, and succeeded in cutting off a large portion of Nagurski’s wind before it was broken. Bronko retaliated by tossing Chewacki out of the ring a couple of times, and the second time the Chief re-entered armed with a heavy board from which protruded a gleaming, tooth-like nail. He was disarmed quickly and given a punch on his distorted beak for the act…the Chief went hurtling through the ropes…a bald-headed gent in row 3 promptly arose and challenged him to a fist fight. Chewacki got in some dirty work…gnawing on Bronko’s arm like a mongrel biting into a juicy bone. He drew blood, and Nagurski…[gave] the Indian the old heave-ho. The Chief bounced up and down like an elevator with the [hiccups] before Nagurski piled on and pinned him for three…”1

But this wasn’t just any old fight in a dark D.C. garage, it was the main event of a professional wrestling show featuring Chicago Bears legend Bronko Nagurski and the dastardly Chief Chewacki at Turner’s Arena, home to the most exciting bouts in the city. Throughout the building’s life, countless wrestlers entertained crowds both in person and on television in the D.C. area, but its influence would extend much further. The venture that started at Turner’s Arena would evolve into the global wrestling juggernaut, World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE).

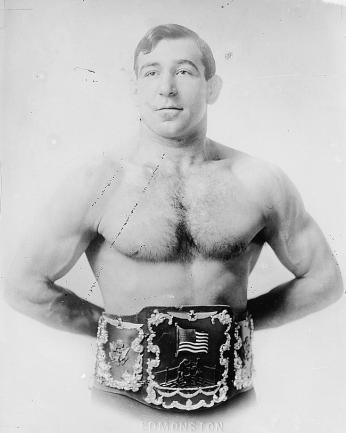

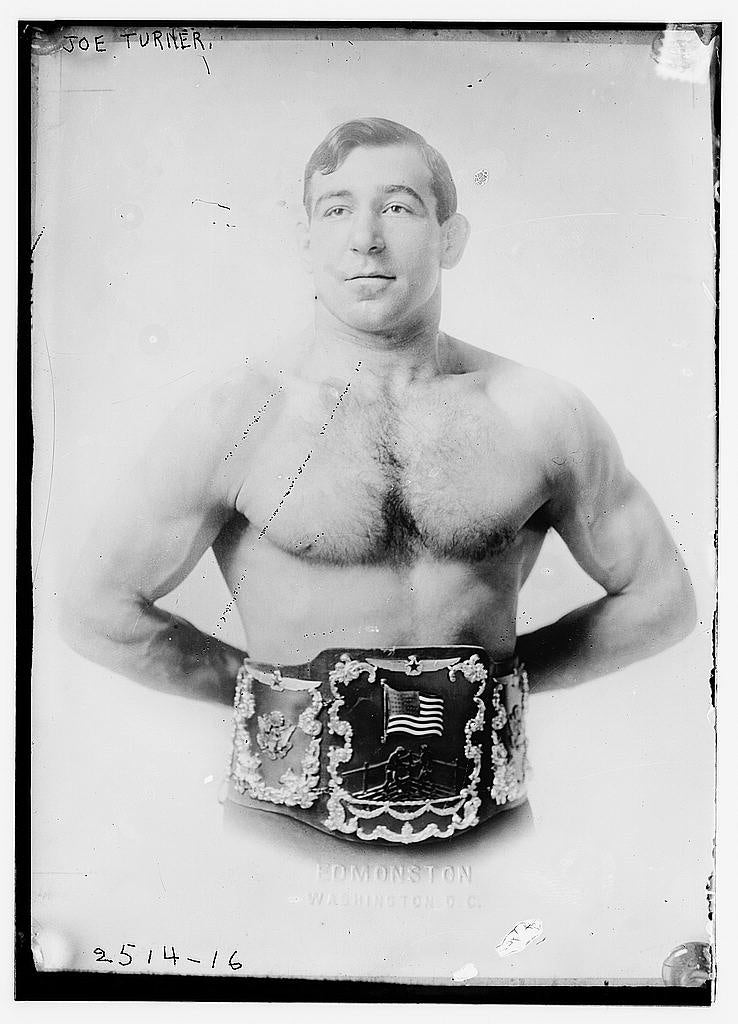

William Joseph “Joe” Turner was born on February 17, 1885, in Bowie, MD.2 Upon moving to D.C., Turner began amateur wrestling in 1904, taking on all challengers at the Georgetown Boys’ Club, before beginning his professional career two years later.3 In those days, amateur and pro-wrestling were both legitimate athletic contests. Later, pro-wrestling would evolve into the scripted performance that we see today. Though Turner failed to win the World Middleweight Championship in 1911, Police Gazette Magazine awarded him an honorary championship dubbed the “Police Gazette Belt” which he held for most of his wrestling career.4

By the 1930s, Turner had retired from the ring and decided to pursue a life of managing events in D.C. at venues including Griffith Stadium and the Washington Auditorium.5 Meanwhile, pro-wrestling had become more mainstream. Across the country, arenas drew large crowds as people used whatever money they could put aside to distract themselves during the Great Depression.6 Originally partnering with promoter “Toots” Mondt, Turner soon went out on his own after a falling-out between the two.

On October 13, 1935, he “leased…a large fire-proof building in the rear of 1341 W St NW, which will be used as his indoor sports arena,”7 the Washington Post noted. The building would include a ticket office, a concessions stand, and a dressing room with showers as well as 1,800 seats, with 700 extra seats on the floor, all facing towards a center platform. While the arena would host all sorts of different events, its connection to boxing and – especially – wrestling stands out. Christened “Joe Turner’s Arena,” it opened for business on December 2, 1935, with a boxing match between Phil Furr and Sid Silas in front of 1,500 raucous fans.8 The first wrestling show followed three days later, with the first match featuring Chief Chewacki, who was an Italian-American named George Mitchell portraying a Sioux Indian. Chewacki would become a villainous mainstay of Turner’s Arena.9

By the time the arena opened, pro-wrestling had evolved into a vastly different attraction than it had been when Turner was competing thirty years earlier. It had become less of a competition and more of a spectacle. Some lamented the change, but not Joe Turner. “I wrestled in those ‘good old days,’ and let me tell you one thing: We had few men to compare with the present crop. The ordinary [ticket sales] in those days didn’t compare with ours, week in and week out.”10

As part of the show, the wrestlers at Turner’s arena adopted larger-than-life personas, often playing on the performers’ ethnic heritage – both real and concocted. In particular, Turner’s shows featured a large cast of Native American – or Native American impersonating – combatants. In almost every case, they were described using the term “Redskin” and designated as “Chief.” Stereotypes of stoic Indians with headdresses and war-cries abounded. Chief Joseph War Eagle and Chief White Owl, who pioneered devastating moves such as the Indian Deathlock and the Tomahawk Chop, respectively, used their heritage to appear both vile and fatal. Others included Chief White Feather, who once fought Ginger the Wrestling Bear,11 and Chief Saunooke, who later was elected as the actual chief of his Cherokee community and as Vice President of the National Congress of the American Indian.12

Whether these stereotypes were harmful to the Native American community at large is up to debate. On the one hand, performers could use their heritage in the ring for profit. On the other hand, they were often made out to be villains, constantly subjected to a chorus of boos and calls for blood. It wasn’t until the 1970s when performers like Chief Jay Strongbow (an Italian-American named Luke Scarpa) and Wahoo McDaniel became “good guys” in the eyes of the fans.

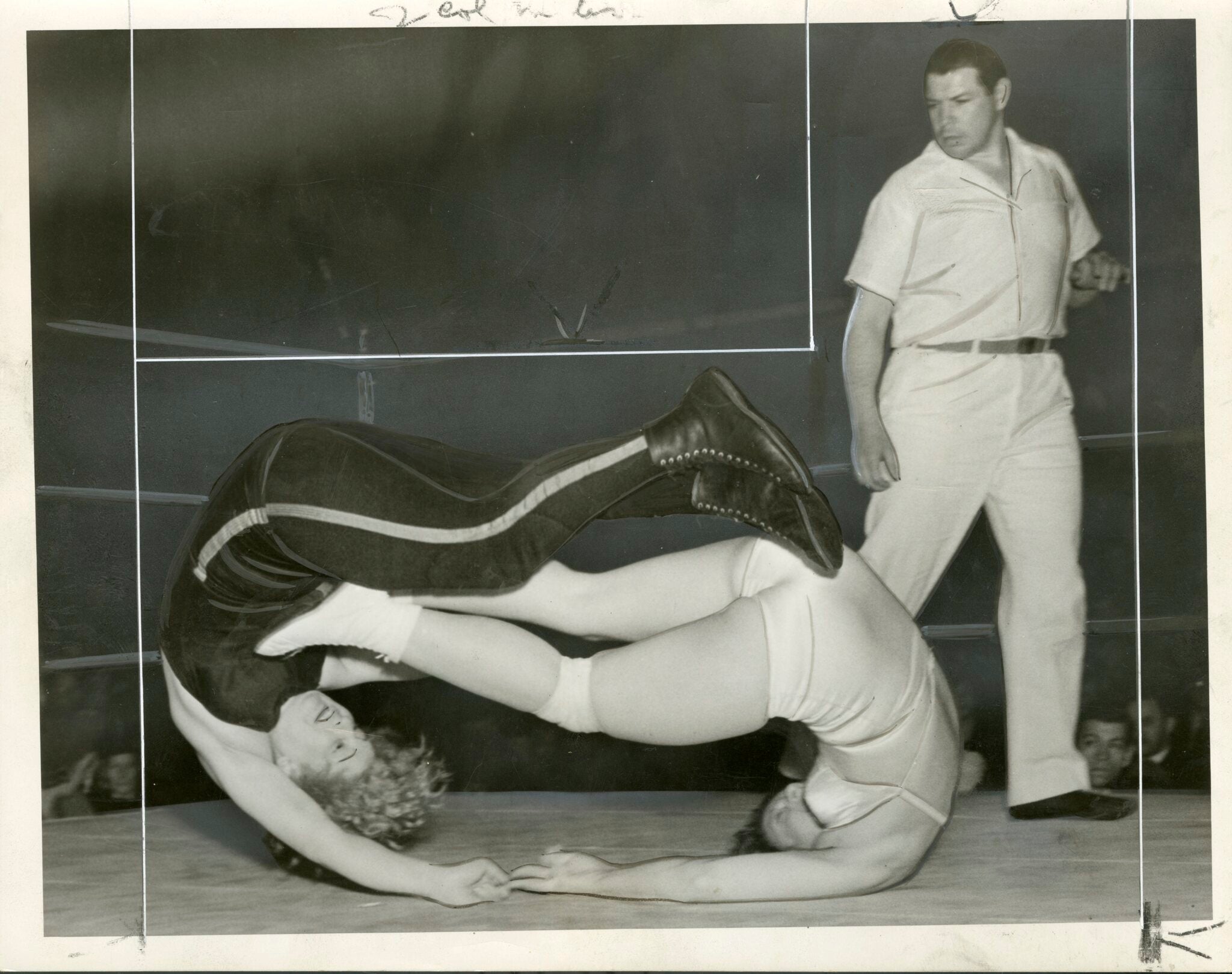

Ever the promoter, Turner hosted his arena’s first clash of “matwomen” on April 10, 1937, between “The Blonde Blizzard” Clara Mortensen and Clarice Davis. Mortensen won the match, showing Davis that “a woman’s place was in the home,” according to the Washington Post.13 But like the Native American performers before them, women wrestlers from any background struggled to achieve credibility. As one reporter opined:

“Some time tonight there should be an ominous rumble in the earth that will develop palsy in practically all the seismographs in the world. It won't be caused by an earthquake, but by thousands of deceased wrestlers revolving rapidly in their graves at the thought of such goings-on as will be taking place at Turner's Arena.”14

Women rarely featured on the marquis, though Turner’s Arena saw several female greats wrestle within its squared circle, including Celia Blevins, Nell Stewart, Gloria Barattini, and WWE Hall of Famers Mae Young, Fabulous Moolah, and Mildred Burke. Many went on to achieve larger fame elsewhere thanks to their tough nature and fiery attitudes including Mortensen, who later starred in the – poorly received – film Racket Girls, where she played a woman wrestler.

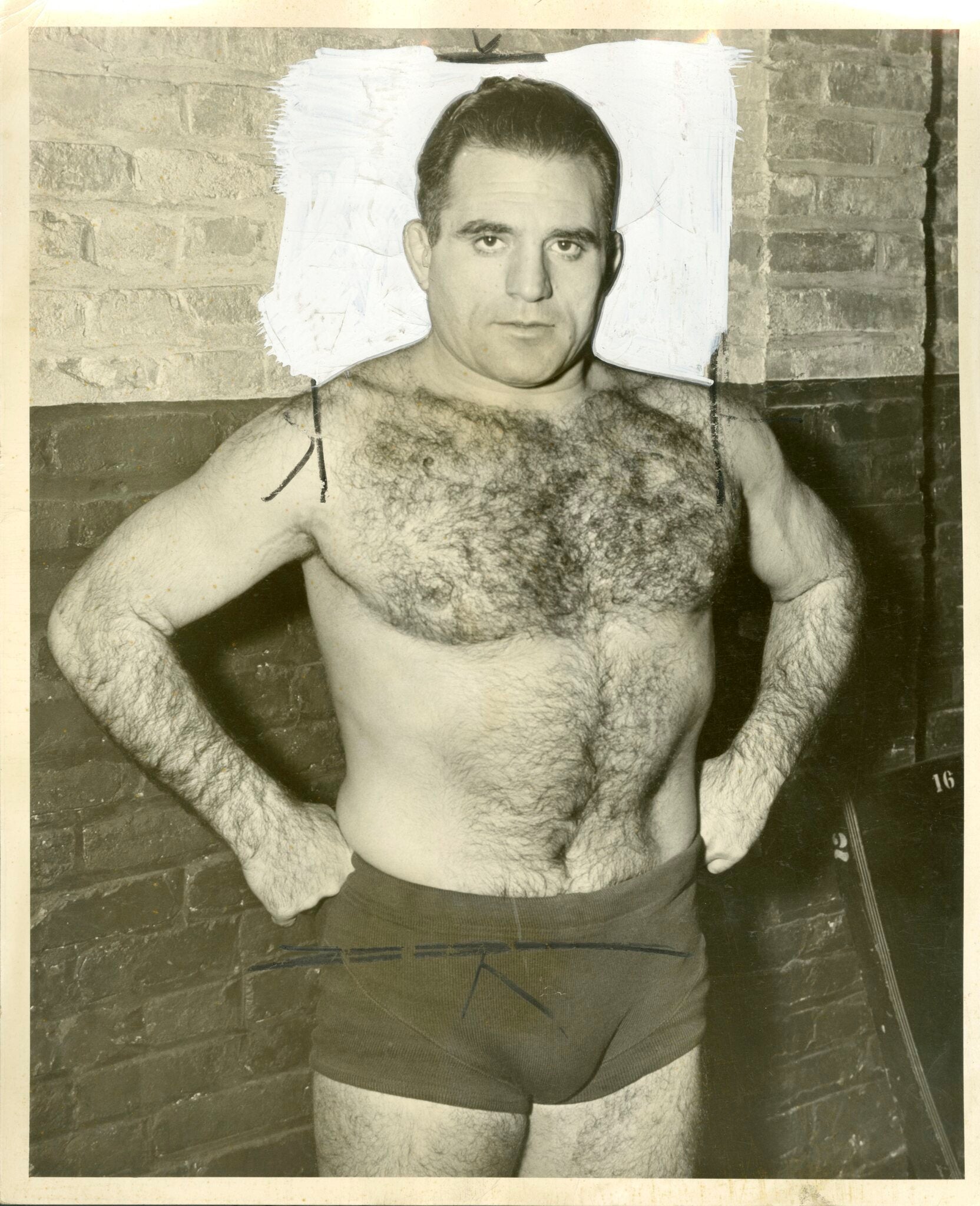

As World War II raged on, Turner’s wrestlers captured the attitudes of the time. Future WWE Hall of Famer “Baron” Michele Leone was one such opportunist. Leone, an Italian immigrant, leaned into the anti-Italian sentiment held by the crowd to become one of the greatest villains in wrestling. While at Turner’s, he dubiously beat many “patriotic” Americans. He also fought a German, miraculously becoming the more villainous of the two in the crowds’ eyes. He even shaved a “V” for victory into his chest hair to signify that Italy would win the war! Crowd sizes increased each week hoping that someone could finally beat Leone once and for all.15 Notable guests of the arena included FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, Vice President Henry Wallace, and countless senators.16

Turner is often remembered as a philanthropist who frequently hosted charitable fundraisers.17 However, at the same time, he enforced strict segregation at his events. Black attendees were forced to sit in objectively worse seats, albeit for a cheaper price.18 In 1941, the Boxing Commission of D.C., suffering from dwindling attendance numbers, forced Turner to integrate his audience. The Commission also argued for introducing mixed bouts, though Turner would only allow for a maximum of two mixed bouts per event.19 Despite further pushback from attendees, Black and White, Turner still stuck to his Jim Crow policy of segregation.20 It wouldn’t be until after his death that the arena would become an inclusive space for all.

Joe Turner passed away on February 18, 1947, most likely from a liver ailment, a day after his sixty-second birthday.21 Turner’s wife Florence married his head-matchmaker, Gabe Menendez, and they briefly ran the business, making Florence one of two female wrestling promoters in the U.S. at the time. The Menendezes hired Vince J. McMahon as the general manager of the arena in 1948 and on December 18, 1952, leased the building to McMahon.22

Attendance initially floundered under McMahon’s leadership. To remedy this, he partnered with Turner’s old adversary, “Toots” Mondt, to bring nationally recognized talent to the arena – through Mondt’s connection to the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) – from 1953 onward. In an era when pro-wrestling was extremely regionalized, the NWA consolidated the different wrestling championships from around the U.S. into one unified NWA World Heavyweight Championship. With this philosophy, they showcased wrestlers across the country at live events and on television as long as they were approved by the NWA board of directors. With their connections, McMahon and Mondt attracted a collection of future WWE Hall of Famers to the arena on W St., including Gorgeous George, Killer Kowalski, Antonio Rocca, Gorilla Monsoon, and Bruno Sammartino. When they weren’t in D.C., they were wrestling at Madison Square Garden in New York City, where McMahon's father, Jess, had previously worked as a boxing and wrestling promoter.

In December 1955, McMahon changed the name of Turner’s Arena to “Capitol Arena.”23 He then negotiated for television slots on the local DuMont network in D.C., WTTG, in hopes of attracting more fans. DuMont was skeptical but McMahon assured them televised wrestling would succeed and agreed to pay for the first two weeks of programming himself. The first show aired at 10 pm on January 5, 1956, and was an immediate hit. DuMont soon approached McMahon to add another two-hour show to the New York DuMont network, WABD. It wasn’t long before his brand of wrestling aired across eleven states under the banner of his new company, Capitol Wrestling Corporation (CWC).24 Meanwhile, Capitol Arena and Madison Square Garden received major boosts in attendance for wrestling events.25

McMahon was ruthlessly territorial of his product. Prior to the 1990s, wrestling promoters had their own “territories” across the U.S. With the introduction of his far-reaching TV show, many old-time promoters in the NWA believed McMahon was encroaching on them. McMahon was frank: “If this is the way television kills promoters, I’m going to die a rich man.”26 When a violinist-turned-wrestling promoter named Ray Fabiani began managing the Uline Arena, McMahon exclaimed “[he] had better keep his musician’s union card because after three shows he’ll be out of wrestling.”27

McMahon’s style of wrestling was dramatic, violent, and chaotic with lots of brawling. It popularized the use of highly fantastical storylines that weren’t as plentiful in other promotions like the NWA, which had a more grounded style. It was beloved by viewers like Gen. Douglas MacArthur and First Lady Bess Truman, who, upon returning to her hometown of Independence, Missouri, said the thing she missed most about Washington was “wrestling on television.”28 The show also garnered plenty of criticism for its graphic themes. A particularly violent match in 1956 between Karl Von Hess and “Wild Man” Jackie Fargo featured Von Hess performing a Nazi salute, Fargo being choked with wire and burned with a cigarette butt, the referee being tossed from the ring, and chairs thrown everywhere. Viewers wrote letters – including some to their Congressmen – to complain.

As one concerned viewer vented, “[t]his is a deplorable situation. The Von Hess-Fargo match was of an atrocious nature. The athletic commission in Washington should be taken to task for permitting such flagrant violation of the rules.” Another asked, “why do wrestlers get away with murder in D.C.?” Still another wrote, “I want to register a vigorous protest over this disgraceful event…the match was shocking and inhuman.” More criticism flowed in:

“For over 50 years I have watched the top wrestlers in this Nation. Never before have I witnessed such brawling, caveman stuff as on the show from Washington. The Capitol Arena should be renamed the ‘Bucket of Blood’...this is poor entertainment…these brawlers use their own rules. The Capitol Jungle Arena is a cesspool.”29

In 1959, a woman in the crowd was kicked in the head by a wrestler and sued the arena.30 McMahon, ever the showman, replied to these criticisms: “if the show doesn’t appeal to you…watch something else.”31

In January 1963, CWC severed ties with the NWA to form the World-Wide Wrestling Federation (WWWF) following a dispute regarding who the rightful NWA World Heavyweight Champion was: the NWA’s choice, challenger Lou Thesz, or the WWWF’s choice, champion “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers. Rogers dropped the title to Thesz, leading to the eventual split. Rogers was then christened the first WWWF Champion and headlined events at both Capitol Arena and Madison Square Garden.32

As it turned out, Washington’s days as a wrestling hotbed were dwindling. In 1965, Capitol Arena was sold to the Washington City Orphan Asylum and subsequently torn down. As the Washington Post noted during the arena’s last days, some called it “the finest arena in the South.” McMahon admitted “it was never a cathedral," but it held a special spot in the history of pro-wrestling. “We’re going to miss the old place,” he remarked. “They’ll probably start tearing it down on my birthday.” McMahon moved his promotion to Madison Square Garden, which boasted attendance numbers ten times that of Capitol’s upon its closure.33

From its home in New York, McMahon’s WWWF – later the World Wrestling Federation (WWF) and later still WWE – would become a global sports-entertainment juggernaut, enthralling millions around the world for decades. Vince McMahon’s son Vince K. McMahon (aka Vince McMahon Jr.) purchased the company from his father in 1982. Against his father’s wishes, McMahon Jr. further expanded the promotion through national television deals on NBC, TBS, and the USA Network.

Today WWE is a publicly traded company worth nearly $9 billion and home to some of the world’s most recognizable stars. Its humble origins are now a distant memory to most fans. But in Washington, it’s fun to remember that – as Vince McMahon Sr. put it – “all of this grew out of the little garage on W street.”34 Indeed, for a generation of District wrestling fans, Turner’s Arena was the place to go to experience an evening of violent entertainment for all.

Footnotes

- 1

Lewis F. Atchison, “Nagurski Is Victor Over Indian Rassler: Redskin Grappler Gets Too Enthusiastic Over Mat Title and Nagurski Gives Him the Works in 17 1/2 Minute – Good Crowd Sees Show,” The Washington Post, February 18, 1938, sec. Local News.

- 2

Al Costello, “Joe Turner, Sports Figure, Dies Here: Joe Turner, Promoter, Wrestler And Philanthropist Dies at 62,” The Washington Post, February 19, 1947.

- 3

“Wrestlers Open for Challenges,” The Washington Post, September 29, 1904.

- 4

“World Middleweight Title (District of Columbia & Mid-Atlantic),” Wrestling-Titles.com, accessed September 19, 2024, https://www.wrestling-titles.com/us/dc/dc-world-m.html.

- 5

Bob Considine, “Joe Turner Flaunts Londos’ Pact With $10,000 Stipend: Promoter of Bout With Dusek Here Tuesday Has Contract Proudly on Exhibition at Office; 15,000 Expected to See Match,” The Washington Post, August 7, 1931, sec. Sports; “Ranking Pair to Wrestle Friday: Steele and Shikat Top Joe Turner’s Card at Auditorium.,” The Washington Post, October 13, 1931, sec. Sports.

- 6

Karl Sterne, “Ultimate History of Pro Wrestling Index - DragonKingKarl Presents the History of Pro Wrestling,” When It Was Cool, accessed October 13, 2024, https://www.whenitwascool.com/ultimate-history-of-pro-wrestling-index.

- 7

“Shannon-Luchs Releases List Of New Leases: Fight Promoter Joe Turner Rents Large Building for Indoor Arena,” The Washington Post, October 13, 1935, sec. Real Estate.

- 8

Bill McCormick, “Furr Batters Sid Silas to Retain His District Welter Crown: Kindly Towel Ends Bout In 13th Champion Rallies to Win as 1,500 Watch at Arena Opening. Kirk Burk Slops Ferrar in 4th; Landers Bows to Eddie Burl. Furr Keeps Title As 1,500 Watch,” The Washington Post, December 3, 1935, sec. Sports.

- 9

Atchison, “Nagurski Is Victor Over Indian Rassler.”

- 10

“Joe Turner and Joe Grant Debate Old and New Wrestling Methods,” The Washington Post, July 15, 1933, sec. Sports.

- 11

“White Feather Fights Bear Tonight on Mat: Ginger Reported Out Of Condition for Bout At Turner’s Arena,” The Washington Post, April 11, 1940, sec. Sports.

- 12

Legendary Chief Saunooke Mourned by Great and Small,” The Smoky Mountain Times, April 22, 1965, 1 edition, Digital NC.

- 13

Bill McCormick, “Ladies Billed as ‘Tops’ but Men Succeed in Causing Riot,” The Washington Post, April 11, 1937, sec. Sports.

- 14

“Matwomen To Provide Fun Tonight: ‘Lightweight Champion’ One of Principals in Hair-Pulling Bout. Legion to Benefit From Lady Wrestling Debut in Arena Card,” The Washington Post, April 10, 1937, sec. Sports.

- 15

Steve Bryant, “SoCal Legend Baron Michele Leone Biography,” SoCalUncensored.com, February 7, 2004, https://socaluncensored.com/2004/02/07/socal-legend-baron-michele-leone-biography/.

- 16

“Fan Faces at Mat Bout,” The Washington Post, 1971, sec. Sports, Sports Wrestling-1971, The Peoples’ Archive; Dave Brady, “Sports, Entertainment, Politics Were at Home at Turner’s Arena,” The Washington Post and Times Herald, June 16, 1964, sec. Sports.

- 17

Fred Sanford, “William Joseph ‘Joe’ Turner (1885-1947)” Find A Grave, September 27, 2011, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/77177325/william_joseph-turner.

- 18

“Jim Crow Policy of Ofay Promoter Irks Fight Fans: Segregation at Washington Arena Is Called’ ‘Necessary for Order.’ Rival Groups Seek Joe Louis for Bout. Link McDonald’s Name, with Joe Turner.,” Afro-American, May 11, 1935.

- 19

Louis Lautier, “Joe Turner Draws Ire Of District Fans: Segregation Is Main Issues In Capital City,” New Journal and Guide, March 1, 1941.

- 20

“Two-Way Jim Crow: Mixed Crowds Banned at Kirsch Dances,” Afro-American, February 23, 1946, Turner’s Arena-1971, The Peoples’ Archive.

- 21

Costello, “Joe Turner, Sports Figure, Dies Here.”

- 22

Dick O’Brien, “Mrs. Menendez Leases Arena to New Group,” The Washington Post and Times Herald, December 19, 1952, Turner’s Arena-1971, The Peoples’ Archive.

- 23

“Turner’s Arena Changes Name For TV Shows,” The Washington Post and Times Herald, December 25, 1955, sec. Sports.

- 24

Herman Blackman, “McMahon’s Gamble on TV Wrestling Pays Off,” The Washington Post and Times Herald, February 2, 1958, sec. Sports; Will Burns, “The Origins of the WWF – Part Two,” Project WWF (blog), January 29, 2021, https://projectwwf.com/2021/01/29/the-origins-of-the-wwf-part-two/.

- 25

Burns, "The Origins of the WWF - Part Two."

- 26

Lawrence Laurent, “Grunt-and-Groaners Pin Down Another TV Myth,” The Washington Post and Times Herald, March 10, 1956, sec. Radio and Television.

- 27

Bob Addie, “Bob Addie’s Column…,” The Washington Post and Times Herald, January 4, 1956, sec. Sports.

- 28

William Gildea, “All Lights Go Out at Capitol Arena,” The Washington Pos and Times Herald, June 27, 1965, sec. Sports.

- 29

Herman Blackman, “Rough Wrestling Tactics Irk Television Fans,” The Washington Post and Times Herald, October 25, 1956, sec. Sports.

- 30

“Woman Kicked at Wrestling Match Loses Suit Against Capitol Arena,” The Washington Post and Times Herald, June 6, 1959.

- 31

“Promoter Answers TV Complaints,” The Washington Post and Times Herald, October 27, 1956, sec. Sports.

- 32

Will Burns, “The Origins of the WWF – Part Three,” Project WWF (blog), February 5, 2021, https://projectwwf.com/2021/02/05/the-origins-of-the-wwf-part-three/.

- 33

Gildea, “All Lights Go Out at Capitol Arena.”

- 34

Gildea, "All Lights Go Out at Capitol Arena."

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)