Wishing in a Fountain: The Protest for More D.C. Pools

In the early 1960s, the Evening Star called the Columbus Circle fountain in front of Union Station “a ready made swimming pool with ledges, platforms, and friendly statues. It is a grand place to wrestle and splash during the heat of the day, to get the shivers, and to finally recapture the heat by stretching full length on the warm bricks of the surrounding walk. Columbus looks on — pleased and noble.”[1]

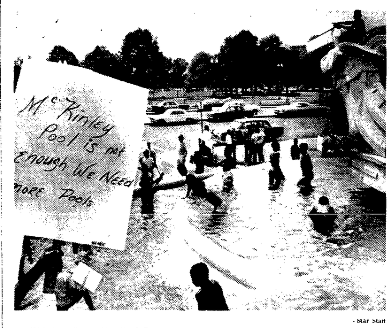

However, as inviting as it was, swimming in the fountain was technically against Park Police regulations...[2] which made it the perfect place to protest Washington’s shortage of accessible swimming pools. And so, on the steamy afternoon of August 2, 1966, dozens of inner-city children from the “heavily populated and poverty stricken” Second Precinct [today home to Shaw and Logan Circle] did just that.[3]

For over 30 minutes, they "splashed at the feet of Columbus amid orange peels and candy wrappers.” Meanwhile a throng of approximately 125 parents and other children who weren't swimming held picket signs with slogans such as “give us a pool because a pot ain’t too cool.” Workers from Neighborhood Development Center No. 1 on 9th St. NW looked on, supervising the demonstration.[4]

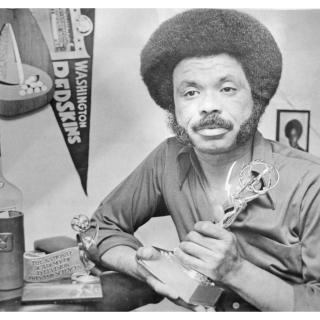

At 2:15 p.m. Seargeant Milton R. Lomax of the National Park Police, unaware that the protest was about to end, confronted one of the workers and told him he was “endangering these children’s lives by having them swim in the fountain’s unsanitary water.” That worker happened to be Petey Greene, future star of WOL Radio’s “Rapping with Petey Greene” and WDCA Channel 20’s “Petey Greene’s Washington.” Greene told the officer that the young swimmers were “out here on their own.” Then he and the other organizers decided to keep the protest going for five to 10 more minutes because of Lomax’s intervention.[5]

The problem, as Greene told the Evening Star, was an inequitable distribution of recreation facilities:

If they had 17 pools, they should have spread them evenly throughout the city, not just in Southeast and Southwest.”[6]

Greene was alluding to the United Planning Organization (UPO, an entity created in 1964 as an arm of the War on Poverty) and the D.C. Department of Recreation, which had promised to set up portable pools that summer but left residents of the Second Precinct sweating — literally. By early August, only four of the pools had actually been built, all of them in Southeast Washington.[7] The closest place for Second Precinct residents to take a dip was the McKinley Pool at Lincoln and T Streets, too far away for young children to walk to.[8]

But why were these pools so unevenly spread in the first place?

The answer had its roots in the District’s longstanding swimming pool segregation policies.

For years, Washington’s public swimming facilities – including, for a time, the Tidal Basin – were strictly segregated. Though the struggle to integrate pools was technically won in 1950, a full 16 years before the Columbus fountain protest, the victory was not so clear-cut.[9] Like many other Civil Rights milestones, just because pools were legally open to everybody did not mean everyone had equal access to them.

No new public pools were built in D.C. between 1935 and 1963.[10] The ones that did exist were primarily located in white neighborhoods, and the few that were in African-American neighborhoods were often too far away for children to walk to or were in poor condition.[11] Case in point: McKinley pool, only recently reopened by the time of the Union Station protest, had been closed since 1961 — five whole years — because of corroded piping. On July 7, 1963, 65 adults and children picketed in and around the drained swimming pool. Signs that read “We’re sweltering” and “We have to walk 20 blocks to a pool” prompted city officials to open the Cardozo High School pool for the summer to appease protesters.[12]

To tackle this ongoing problem with accessibility, the UPO had promised in the spring of 1966 to establish a Neighborhood Youth Development Program (NYDP) in the area of the Second Precinct. This program was supposed to employ older kids to help with recreation by organizing councils and neighborhood centers.

Future U.S. Senator Richard Blumenthal — then a young reporter for The Washington Post — explained, “the councils will provide an outlet for expression — give youngsters from low income areas an opportunity to debate common problems, meet and negotiate with city officials for improved schools and new parks.”[13]

But the NYDP, scheduled to begin on July 15, 1966, still hadn't started by the time of the Columbus Fountain protest on August 2. It was postponed twice throughout the summer, with the excuse that the UPO could not find nine qualified community organizers with master’s degrees in social work and experience in field work and clinical psychology.

Blumenthal reported on the lengthy staffing hang-up:

The directors said they did not expect the delay would affect operation of the program seriously. But they acknowledged that it has aggravated problems of finding space and equipment for recreation, offices for secretaries and neighborhood workers, and meeting rooms.”[14]

Whether or not NYDP directors thought the delay was serious, residents of Cardozo certainly did. Teenagers from that area formed a group known as the “Saints” to picket the UPO throughout the summer of 1966 and ensure that the NYDP could get started.

By the end of July, community organizers for the program were still yet to be hired. Karl Gudenberg, director of the NYDP, reportedly told 60 members of the Saints picketing the UPO that anyone hired “must have a college degree."

By the time you get through college,” one picketer responded, “you’re square.” Another, Mary Rivers, observed, “They just want to give us another Uncle Tom. Someone they can control.”[15]

This frustration with the UPO was a major part of the Columbus Fountain protest. During the demonstration, Petey Greene told The Washington Post:

These kids are worried about the Neighborhood Youth Program. They’re hollering about why there aren’t any recreation facilities yet. They want a building they can call their own with pool tables and stuff.”[16]

The protest at Columbus Fountain lasted only 30 minutes, but it made a big splash. That very evening, at a "stormy session” held at St. Stephen and Incarnation Episcopal Church, Karl Gudenberg told the Saints he would spend “a fair amount of time” discussing with them and helping them draft a proposal for a local youth center.

According to an article in the Evening Star, “Gudenberg applauded the Saints’ spirit, saying ‘I would hope that you could take the leadership in this area.’ He added the Saints would have to convince UPO they were representatives of ‘the thousands of kids who live around here.’”

The Saints accepted Gudenburg’s offer, and by October of 1966, a newly formed Youth Planning Committee submitted a plan tailored to neighborhood needs to be staffed by the NYDP. [17]

Youth representatives from other parts of the city got involved too, and by the summer of 1967, Betty James of the Evening Star noted, “Washington has a beautiful blueprint for special leisure-time summer programs for at least 34,000 children and youth—a program they helped design.”

That summer, fifteen shallow “walk-to-learn-to-swim” pools were built for small children throughout the city, and four new major pools were built in Southeast and Southwest. New parks and recreational programs were promised for that summer as well.

But the youth representatives, after working hard to give input on recreation programs, received discouraging news. Congress gave only a fraction of requested funding for the programs, throwing a wrench in the collaborative plans.

Ernest Middleton, a worker from the UPO center in Lower Cardozo, expressed his disappointment:

And now they are told that the money may not be available...The kids are asking what the heck did they do all that planning and hoping for?”[18]

Continual funding cuts eventually led the NYDP to be disbanded entirely in March of 1968, leaving some to wonder whether the ideas of the youth would ever be taken seriously.[19]

As Petey Greene said at Columbus Fountain, access to recreation was “only one problem in a generational protest.”[20]

Footnotes

- ^ “Fun in a fountain,” Evening Star, August 13, 1961: 169, accessed June 11, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ Although it had long been prohibited, this wasn't the first time children swam in Columbus Fountain. It was just never done in protest before. "Delight for Street Youngsters in Plunge at Columbus Fountain." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jul 18, 1922. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest…. "Columbus Discovered America, they Discovered Relief!" The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Jul 18, 1963. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest….

- ^ “Cardozo ‘Saints’ Win Pledge of Aid In Drawing Up Youth Center Plan,” Evening Star, August 03, 1966: 25.

- ^ "Children Splash in Fountain to Protest Pool Lack." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Aug 03, 1966. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/docview/142767472?accountid=57895.

- ^ Ibid., and "Cardozo ‘Saints’ Win Pledge of Aid In Drawing Up Youth Center Plan,” Evening Star, August 03, 1966: 25.

- ^ “Cardozo ‘Saints’ Win Pledge of Aid In Drawing Up Youth Center Plan,” Evening Star, August 03, 1966: 25.

- ^ “2 More Pools to Open, 13 Under Construction,” Evening Star, August 07, 1966: 85, accessed June 12, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ “Cardozo ‘Saints’ Win Pledge of Aid In Drawing Up Youth Center Plan,” Evening Star, August 03, 1966: 25.

- ^ "Non-Segregated Swimming Pools to Remain in D.C.," Atlanta Daily World (1932-2003), Sep 17, 1950, https://search.proquest.com/docview/490916184?accountid=46320

- ^ “DC Supports Plan to Provide 15 Public Pools,” Evening Star, September 25, 1963: 27, accessed June 10, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ Wiltse, Jeff, Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America, (The University of North Carolina Press: 2009), 154-195.

- ^ “Cardozo Pool Opening Seen Cutting Protest,” Evening Star, July 07, 1963: 4, accessed June 10, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ Blumenthal, Richard. "UPO Meets Snag on Youth Program." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Jul 26, 1966, https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/docview/142662088?accountid=57895.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ "Cardozo Area Youths Picket UPO," The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973),Jul 29, 1966, https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/docview/142821268?accountid=57895.

- ^ "Children Splash in Fountain to Protest Pool Lack." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Aug 03, 1966.

- ^ “Youth Unit Details Its Own Proposal for D.C. Program,” Evening Star, October 20, 1966: 26, accessed June 10, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ James, Betty, ”A Race With Summertime,” Evening Star, May 14, 1967: 1, accessed June 11, 2019, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:13D5DA85AE05A305…@?p=WORLDNEWS.

- ^ Raspberry, William. "Hill Ax Threatens Useful Youth Setup." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Feb 28, 1968. https://library.access.arlingtonva.us/login?url=https://search-proquest….

- ^ "Children Splash in Fountain to Protest Pool Lack." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Aug 03, 1966.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)