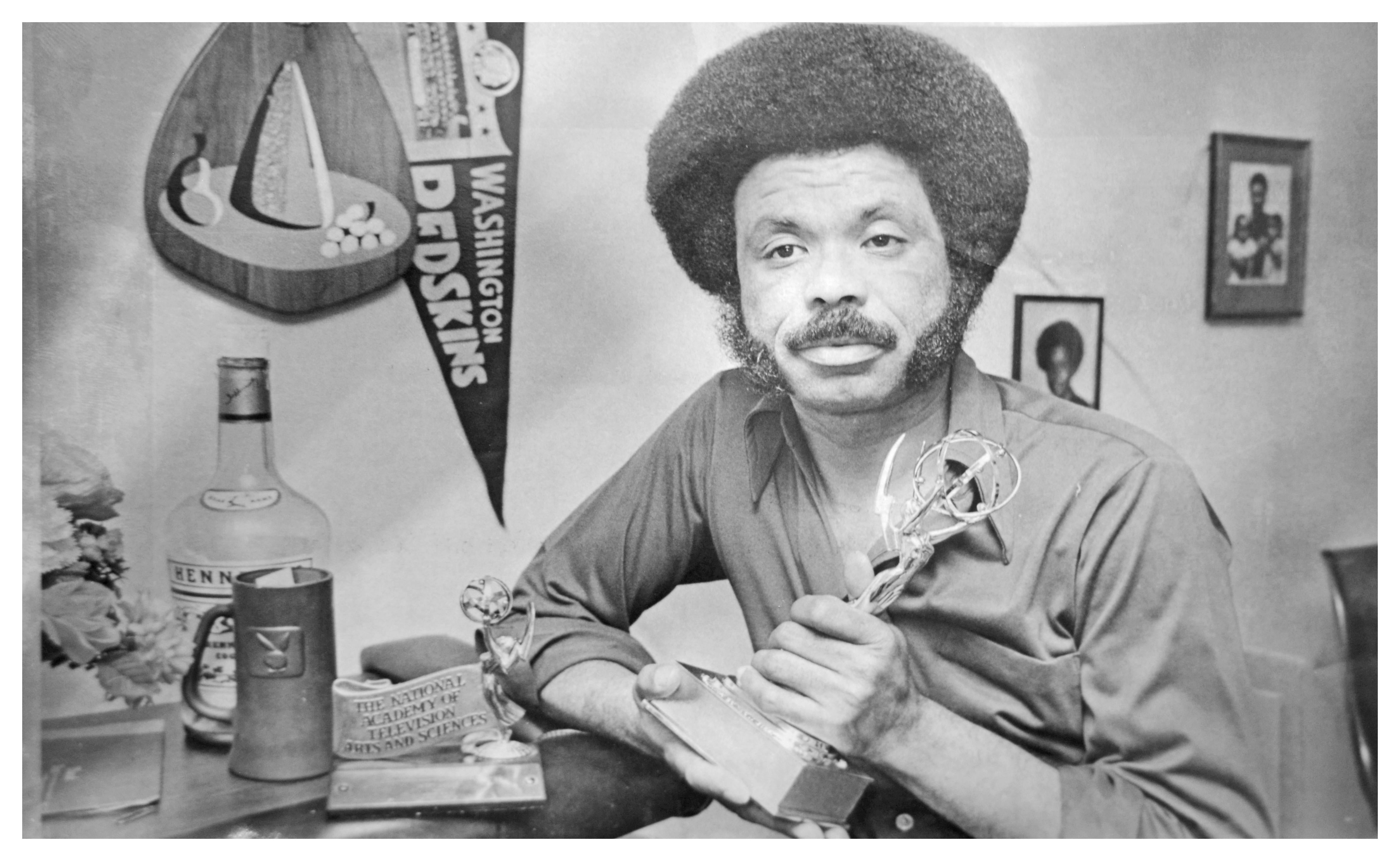

Petey Greene Talks Down the Riots, 1968

"God gave me a talent, and that talent was verbal skills."[1] Critically acclaimed as America’s first “shock jock,” Petey Greene had the mouth and charisma to roar in the ears of people in the streets of Washington, D.C. His impact was no more apparent than in April of 1968 during the aftermath of Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination.

Running down the streets outraged, a group of about thirty young people burst into a drug store. “Martin Luther King is dead,” they shouted. “Close the store down!"[2] 26-year old Stokely Carmichael, former chairman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the initiator of the what became the “Black Power Movement” in 1967, led Washington, D.C. civilians down the streets demanding that all businesses close out of respect of the death of King.

Although the initial goal was to maintain peace, things quickly went out of Carmichael’s hands. Emotions boiled and violence broke out.

Carmichael’s group ran into Walter Fauntroy, then a Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) official, and Fauntroy reportedly said, “This is not the way to do it, Stokely. Let’s not get anyone hurt. Let’s cool it.”[3] Carmichael responded, “All we’re asking them to do is close down the stores.” However, the situation had escalated into a full-fledged riot.

The violence took over the U-street corridor, H-street corridor and other areas of the city for three days as an estimated 20,000 people were involved in the rioting; there were 12 riot-connected deaths[4] and the city lay smoldering. But even as the fires and looting spread, a calming voice on the radio started to break through the noise.

Petey Greene was the uncle of the African-American community in Washington, D.C. Born during the great depression; his young life was marked with drug addiction and imprisonment for robbery.[5] But, while in prison at Lorton Reformatory, he developed a following from prisoners and guards alike for his wit and cutting language, which he honed on the prison’s public address system.

Upon his release from Lorton in 1965, Greene turned to changing the lives of people and the perspectives of black culture on the radio, landing a job at Washington’s R&B station, WOL 1450 AM. His challenging humor and social awareness made it easy for him to connect with members of the black community who he described as being “real poor.”

Sharing the anger that many felt over King’s death, Greene used his position and fame to channel that anger into something else. On air for hours as the riots raged, he urged peace. His message was remembered in the 2008 Independent Lens documentary “Adjust Your Color.”

“I don’t know why we hate each other, we find it so easy to hate when it’s really hard ... but as long as you’re hating you are tearing yourself down mentally and financially.”

Greene’s words were heard, as many credited him for helping bring an end to the riots.

He remained a powerful voice in the District for years afterward, first on radio and then on television. Greene used wit and cutting language that would immediately catch listeners ears; and his programs showed different perspectives of black culture. He never shied away from controversial issues like sexual abuse, race, and social activism and his broadcasts included a range of topics relating to everyday life of African-Americans — everything from lessons on teaching whites how to eat watermelon to his famous theory of “Hustlin’ Backwards.”

"I'll tell it to the hot, I'll tell it to the cold. I'll tell it to the young, I'll tell it to the old. I don't want no laughin', I don't want no cryin', and most of all, no signifyin'. This is Petey Greene's Washington." Petey Greene, a voice that was always heard.

Footnotes

- ^ James Hablin. “How Not to Eat a Watermelon.” The Atlantic (2013): 1. Aug 23. Web. 7 May 2014.

- ^ David Ginsburg A Washington attorney, The Washington Post Co. "The Story of Washington's April Riots." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973): 1. Nov 02 1968.

- ^ James Hablin

- ^ Leonard D.,Jr. "1968 FLAMES OF OUTRAGE." The Washington Post (1974-Current file): 5. Apr 09 1978.

- ^ Richard Traub. “HE BUILDS NEW LIFE THROUGH OWN EFFORT.” The Free-Lance Star (1977): 2. Jan 11 1977.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)