Before K-Pop there was… the Arirang? The First Korean students at Howard University

Today, the K-Pop phenomenon has taken the world by storm; but it seems that American fascination with Korean music goes all the way back to the late 1800s, 1896 to be exact. Long before bands like BTS sold out stadiums, there were seven Korean (then called Chosun) students whose singing captured the attention of “dozens of damsels” at Howard University.[1]

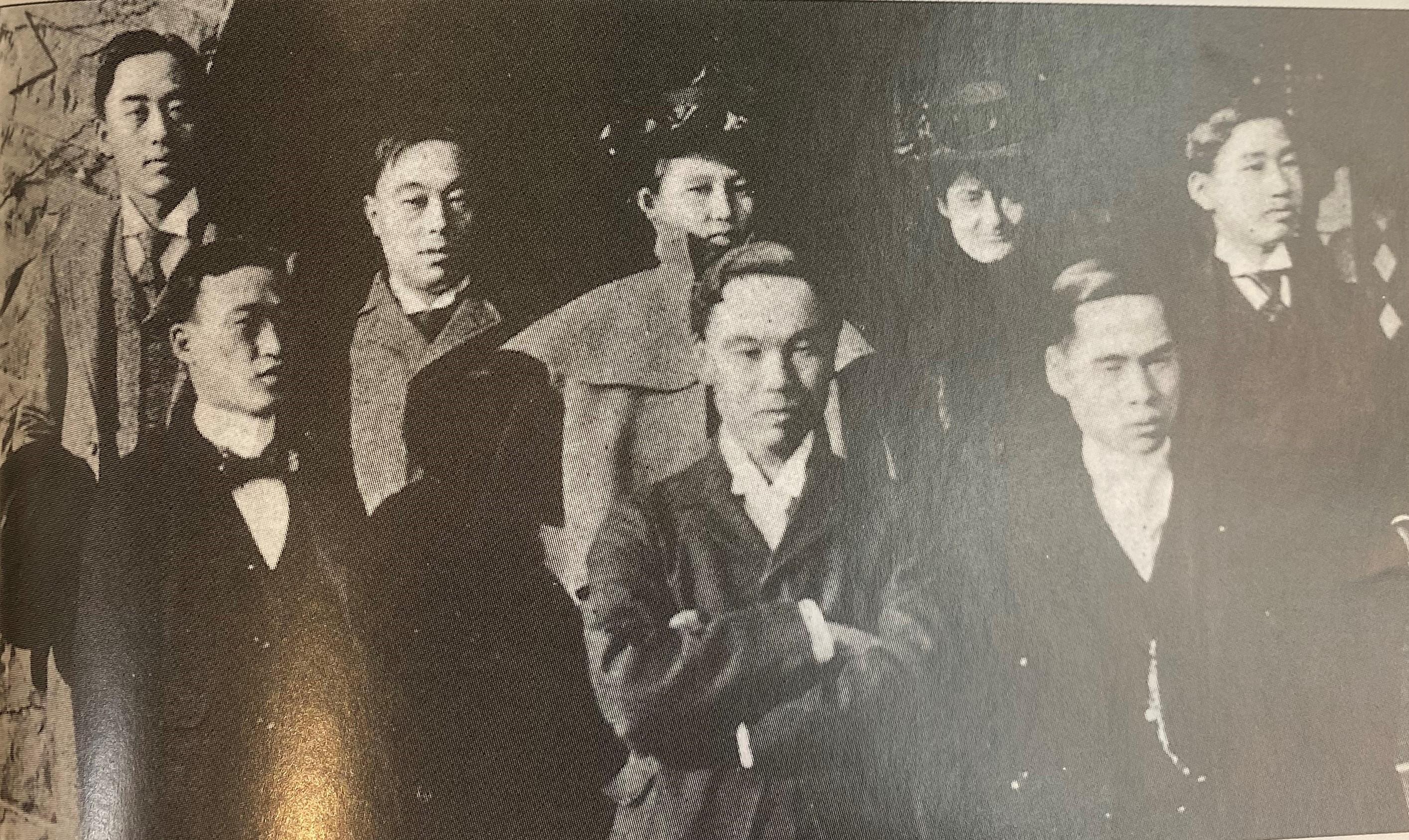

But how did Koreans end up at Howard? That’s quite a story in its own right. According to newspaper records, Im Byung Goo (19), Lee Bum Su (24), Kim Hun Sik (27), Ahn Jung Sik (23), Eyo Byung Hyun (26), and an unnamed student stole 400 won from a Korean bank in spring of 1896 and fled to Vancouver.[2] Having spent all their stolen money travelling, they found themselves in a web of their own making. Their lack of knowledge of English certainly didn’t help the situation either. In a panic, the runaways visited the Japanese Consulate and asked them to telegraph Suh Kwang Bum, the Korean Envoy and Minister Plenipotentiary to the U.S.[2] Lucky for the runaways, Suh likely empathized with their story. He himself, in a sense, also once fled to the States out of necessity.

Suh was one of the very first Koreans to ever visit D.C., accompanying Min Young Ik, a Chosun diplomat and minister, as an envoy in 1883. After the visit, Suh returned to Korea; but his leadership of an unsuccessful coup forced him to flee to America.[3] Suh headed back to Washington, presumably because he had been there before and had some connections.[4] When the reformation movement took power of the Chosun government later in 1891, Suh returned to Korea; but by 1896 he was back in Washington – again – serving as Korean Envoy and Minister Plenipotentiary to the U.S.[4]

Given Suh’s personal experience, it makes sense that he was willing to lend a hand when the seven Korean runaways contacted him also seeking to make America their new home. Suh, in turn, coordinated with Howard University where the runaways were enrolled.

A Washington Post article published in 1896 covered the arrival of the seven Korean students. The article’s byline read: “Seven Koreans at Howard: Ran Away from Home to be Educated in United States. All are sons of noble families, but do not understand a word of English -- will be kept at expense of the Minister from Korea…”[1] The article called the story of the runaways “somewhat wild and romantic.”[1] All the young men were “scions of noble families, and had been established at school in Japan, but instead of remaining there, they took it into their heads to acquire their education in the United States.”[1] The newspaper made no mention of the runaways' theft, but it did remark that “Only the minister and the runaways know the precise nature of the correspondence.”[1] The Post also commented that Suh provided for the students “at [his] personal expense,” but other records suggest Howard University also did much to aid the foreign students.[1]

Historian Ray Logan’s history of Howard University explains that:

On April 29, 1896, the Korean Minister personally requested at the meeting of the Executive Committee, that rooms be provided for…Korean young men. The Committee voted to make them available to them, free of charge, in Clark Hall, provided all other expenses were paid. The Korean minister agreed to pay for the furniture which the Treasurer was to purchase. On May 12, 1896, the Committee noted that the rooms had been fitted for the Korean students.[2]

The same Washington Post article remarked that certain professors from Howard were “interested in their case.”[1] “[The students] will be distributed among the professor’s families during the summer vacation,” wrote the Post, “and their hosts will make it a business to see that they are ‘coached’ in the English language...they now depend on pantomime and what English phrases they have picked up from their journey.”[1]

There aren’t many records of how the Korean students adjusted to Howard University or what they did after their time there, but the few stories of them that remain all suggest the students were best known for their musical abilities. Indeed, The Washington Post noted that they showcased their talents at a “social gathering of the students” that “took place on the night of their arrival.”[1] The Korean men were “solemn, sedate, and observing” and “were surrounded by a dozen persuasive damsels, who begged them to sing.”[1] They communicated that they “could not sing in English, but they were assured that that did not matter, and, after more urging, the programme of ‘Suwanee River’ and like songs was diversified by specimens of real Korean melody.”[1] The article remarked that “It was a unique occasion for everybody concerned,” as it was the university’s “first experience with the Korean.”[1]

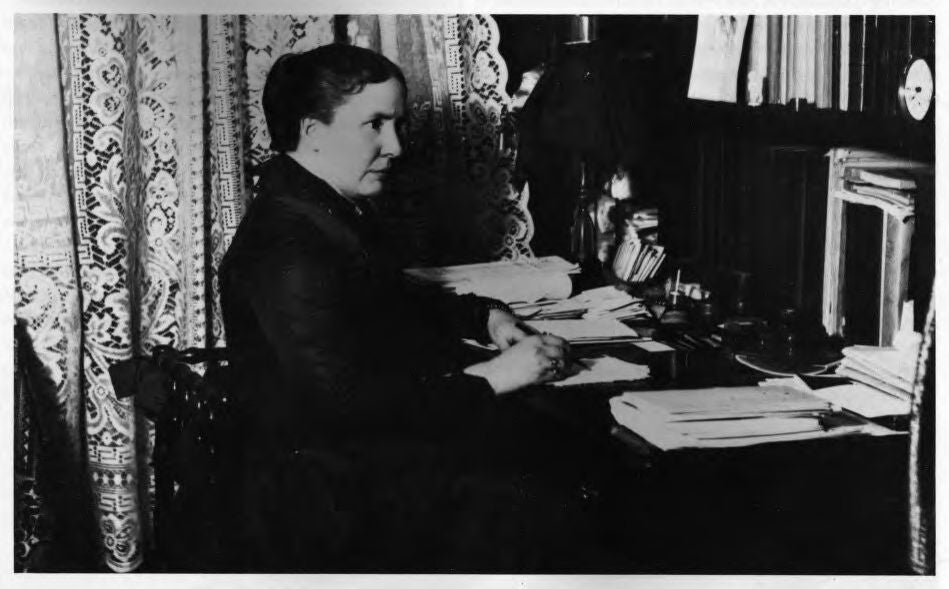

Initially, it seems that the singing was more at the request of “damsels” rather than because the men wanted to perform; however, that may have changed as they got more comfortable at Howard. On July 24th, American ethnologist Alice C. Fletcher invited three of the Korean students to her home in Washington, D.C. in order to produce the first recording of a Korean Arirang, or Korean folk song.[5] Fletcher’s work mainly focused on Native American music, so it’s surprising she showed an interest in the Arirang.[5] Her personal notes from the session don’t indicate any explanation for what piqued her interest or even what she thought of the recordings.[5] But they do give some insight into what the songs were about.

An excerpt from her notes reads:

Jong Sik Ahn. First record:

Not less than 500 years

Out of the valley of many mountains,

Stands the P[illegible]

[…]

not less than 500 years

The prayer that all good [illegible] may not grow old

[...]

In a fine moonlight night in a great

great Anthem Hail his majesty

[...]

Blooming plum tree

Out of the valley of many mts.

older than present dynasty, which is

500 yrs. and more old…

Prayer that all good men, etc….

In a fine moonlight night etc.[5]

While the excerpt above is a translation of lyrics, Fletcher also marked which parts of the recording were more general “love songs,” and according to her notes, the “love song” portion was frequent.[5] It makes sense, then, that Fletcher called the recordings "Love Song: Ar-ra-rang.”[6] It’s unclear how widely circulated the recordings were or what impact they had during their time, but more recently in 2017, the recordings were temporarily exhibited at the fifth annual Seoul Arirang Festival.[7] Today, the six cylinder recordings can be requested at the Library of Congress in their Folklife Reading Room.

At the time of the recording, Suh was in exile having defied government orders to return to Korea, and he was also suffering from chronic tuberculosis. It’s unclear when exactly Suh passed, as some claim as early as August 1896 while other sources claim Suh lived until 1898.[8] The Korean students at Howard reportedly visited Suh regularly until his death.[4] Suh was only between 38 to 40 years old when he died. Lee Bum Jin succeeded Suh as Minister, but according to a history compiled by the Korean Association of Greater Washington, Lee Bum Jin prohibited his staff at the Legation from attending Suh’s funeral, a decision that angered the Korean students at Howard.[4] Suh’s provision and care for the students must have sparked a close relationship between them and Suh.

It would take another 60 years for a substantial number of Koreans to immigrate to the D.C. area; but the story of Suh Kwang Bum and the first Korean students at Howard prove Koreans have been making D.C. home for longer than most believe, and that Americans have long been interested in Korean music.

You can listen to the Library of Congress recording of the Arirang here.

Footnotes

- a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l "SEVEN KOREANS AT HOWARD: RAN AWAY FROM HOME TO BE EDUCATED IN UNITED STATES. ALL ARE SONS OF NOBLE FAMILIES, BUT DO NOT UNDERSTAND A WORD OF ENGLISH-WILL BE KEPT AT EXPENSE OF THE MINISTER FROM KOREA." The Washington Post (1877-1922), May 08 1896

- a, b, c Rayford W. Logan, Howard University: the First Hundred Years, 1867-1967 (New York: New York University Press, 1969), 126.

- ^ Together with several others, Suh staged what’s now remembered as the Gapsin Coup in 1884. The coup aimed to overthrow members of the pro-Chinese conservative faction; but the attempt failed and only reinforced the conservative government. (Si-Woo Lee, Life on the Edge of the DMZ (Kent: Global Oriental LTD, 2008), 317).

- a, b, c, d Young Chang Chae translated by Kyu Won Lee, History of Korean-Americans in the Washington Metropolitan Area: 1883-1993 (Seoul: The Korean Association of Greater Washington, 1995), 28

- a, b, c, d, e Robert C. Provine, “Alice Fletcher's Notes on the Earliest Recordings of Korean Music,” The Academy of Korean Studies, http://www.ikorea.ac.kr/File/intro/Fletcherpreliminaryarticle.pdf

- ^ “Alice C Fletcher collection of Korean cylinder recordings,” Library of Congress Catalog, accessed 28 January 2020, https://catalog.loc.gov/vwebv/search?searchCode=LCCN&searchArg=20156553…

- ^ Yoon Min-ski, “Oldest recorded Arirang to be on display in Seoul,” The Korea Herald, 27 September 2017, http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20170927000618

- ^ Robert Oppenhiem, An Asian Frontier: American Anthropology and Korea, 1882-1945 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2016), 426.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)