A Tale of Two Photographers: Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner

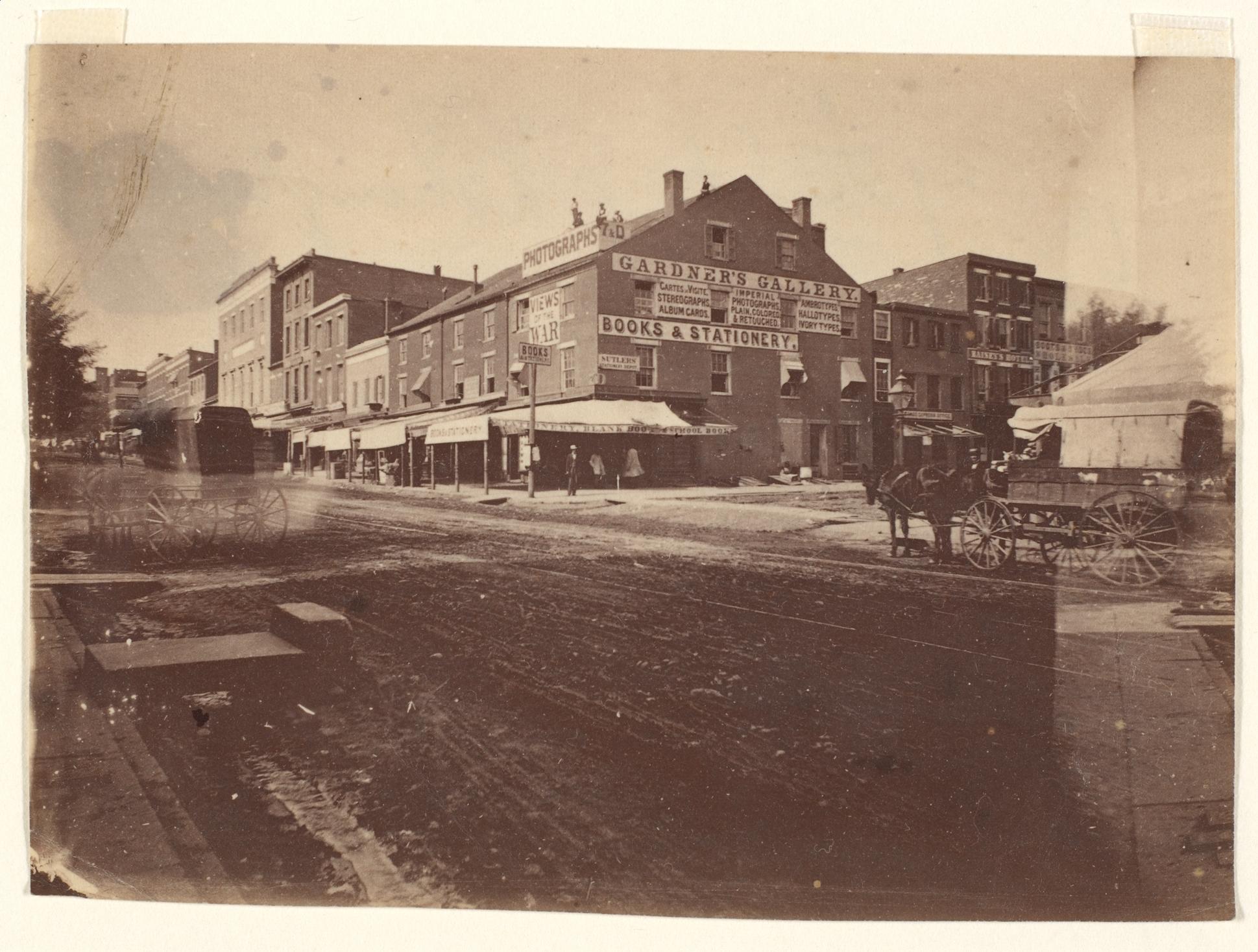

If you lived in nineteenth-century D.C. and wanted your picture taken, you couldn’t just whip out your own camera — you’d visit Pennsylvania Avenue NW, known locally as “photographer’s row.” This stretch of the avenue, between the White House and the nearly-finished Capitol building, was home to a cluster of photography studios and galleries. Between 1858 and 1881, the most fashionable and famous was Brady’s National Photographic Art Gallery.

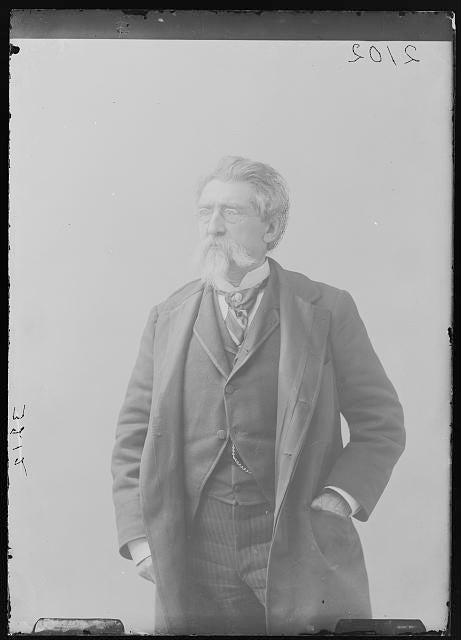

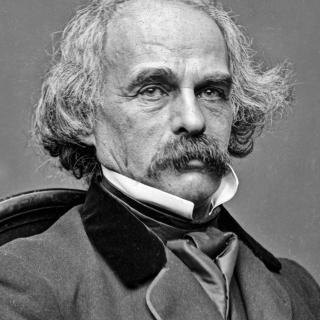

Mathew Brady is probably best known for his work during the Civil War when he took and collected thousands of photographs documenting the aftermath of major battles. But before and after the war, Brady was known as a prominent portrait photographer. In the mid-nineteenth century, when photography was a new and expanding art, Brady pioneered an industry which flourished for well over a hundred years. His studios hosted numerous famous guests: presidents, politicians, authors, actors, socialites, and other “great men” of the nineteenth century. However, Brady’s appetite for celebrity — and his notoriously bad business skills — drove away his biggest asset in Washington: studio manager Alexander Gardner, the man behind some of the most noteworthy images of the war period. Their rivalry had consequences: Brady’s empire collapsed, while Gardner’s achievements and contributions were largely eclipsed by his boss’s fame.

Photography became a worldwide phenomenon in the early 1840s after the Frenchman Louis Daguerre invented his namesake camera. Taking a “daguerreotype” image was a long and expensive process. A photographer treated sheets of copper with hazardous chemicals, exposed them to varying amounts of light and darkness, then developed an image by exposing the sheets to mercury fumes. Those sitting for a daguerreotype portrait would have to remain perfectly still for 60-90 seconds, or else risk a blurry photograph. Even still, recording likenesses had never been easier.

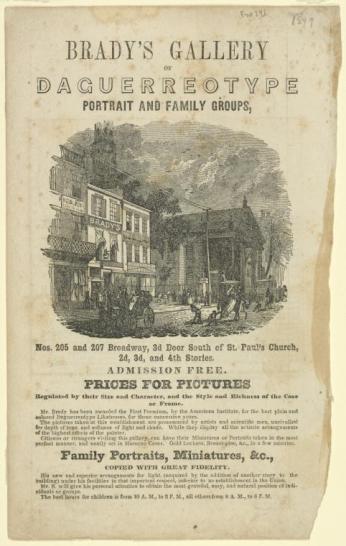

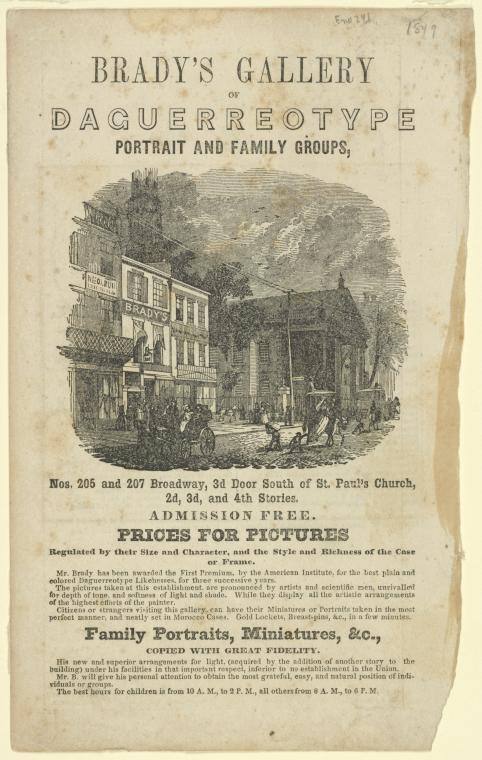

Brady traveled to New York City from his hometown upstate, eager to make a name for himself. What set Brady apart from other budding photographers was his willingness to experiment with the new art. A journal article from 1851 notes that Brady “resolved to bring the Daguerreotype to perfection by elevating it into the dignity and beauty of an art of taste.”[1] When he opened his New York studio in 1844, he advertised a style of formal and artistic portraiture that appealed to high society. He also understood the importance of advertisement. His greatest method for attracting business was what he called his “national portrait gallery”: a window display showing the portraits of well-known people. Clients with some claim to fame could pose for free, as long as Brady got to keep the finished product. Attracting them was slightly more difficult — Brady often snuck into high-profile parties in search of celebrities, trying to lure them back to his Broadway studio.[2] But in order for his gallery to show a variety of notable individuals, Brady needed to photograph the chief notables of the day: the politicians. There was only one place to do that.

Brady first arrived in Washington in 1848, on a mission to photograph as many big names as possible. Luckily, he began with a living legend: former First Lady Dolley Madison, who introduced him to many potential clients. Business must have been good because Brady decided to set up a temporary studio. In early 1849, he rented rooms from a watchmaker on Pennsylvania Avenue and 4th Street NW, in the already-established photography district. During that year’s inauguration celebrations, he photographed the new President Zachary Taylor — a former client — at the White House. But despite his success, Brady fell out with his landlord and faced harsh competition from other Washington photographers. By 1850, he was back in New York.

The next decade marked the peak of Brady’s career as a portraitist. His studio stayed busy thanks to the growing “national gallery.” Patrons could view the famous portraits for free and then, hopefully, travel upstairs for their own sitting. After the development of negative plates, which allowed for the mass reproduction of images, they could also purchase a print of their favorite celebrity. At this point in his career, Brady was rarely the man behind the camera. Contemporary sources confirm that he suffered from severe nearsightedness — a problematic handicap for a photographer.[3] Instead, he oversaw a staff of twenty-five people: photographers, developers, artists, framers, and sales clerks. One of these hires became especially significant for the future of the Brady empire.

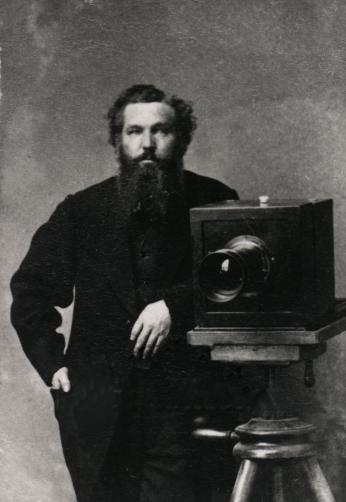

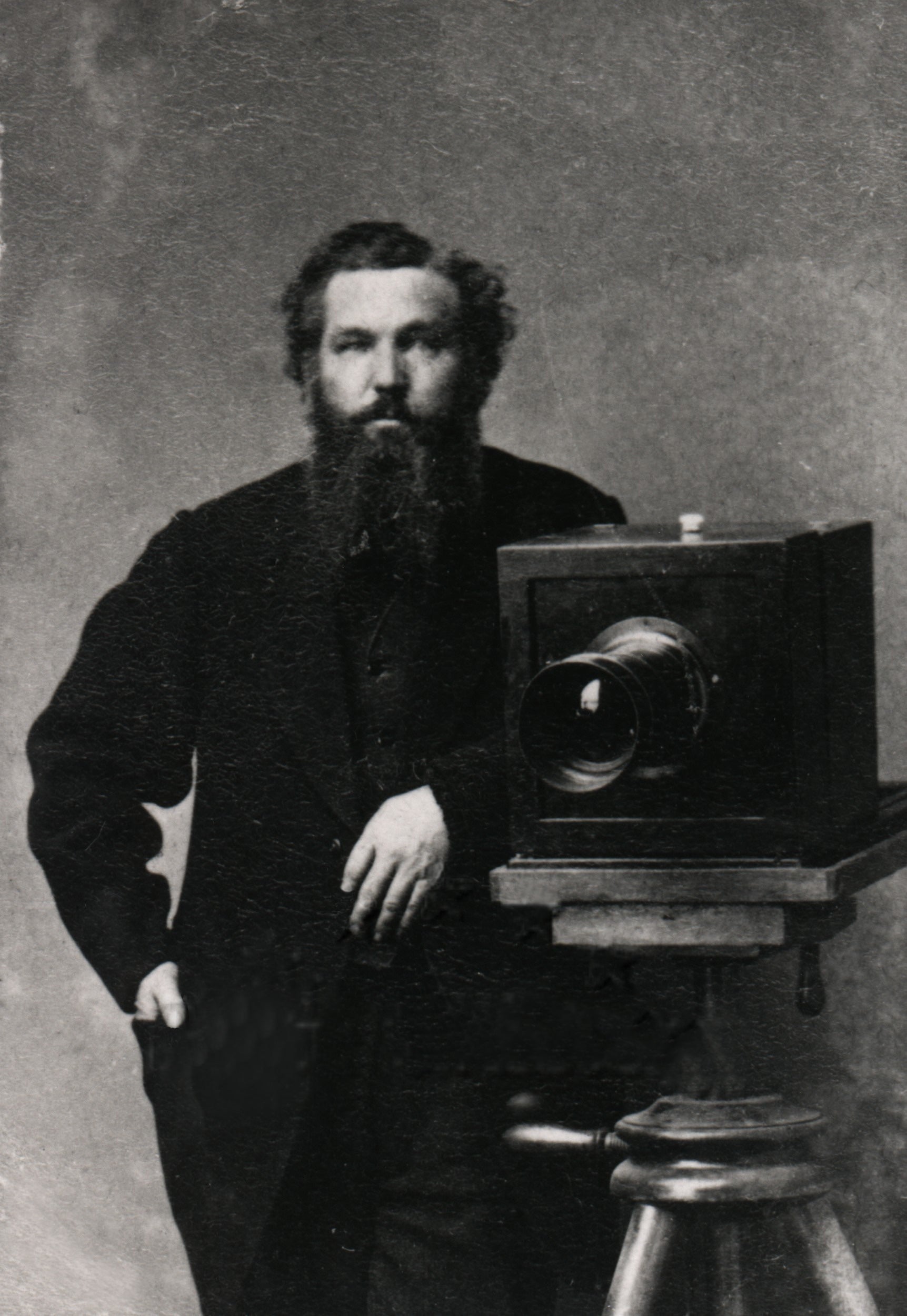

Alexander Gardner came to Brady’s studio in 1856. A Scottish immigrant, he worked as a portrait photographer in Glasgow before he moved his family to New York. Brady was clearly attracted to his new employee’s breadth of experience and business know-how; among his many odd jobs, Gardner had owned and operated a successful weekly newspaper. He also specialized in taking large photographs and developing enlarged prints, something previously unknown at the Broadway studio. As they developed a positive working relationship and partnership, Brady began to rely on Gardner more than any other employee. So, when Brady decided to give Washington another go, he made Gardner the studio’s new manager.

Despite abandoning his first D.C. studio in 1850, Brady never gave up his desire for a second branch in the capital. It made sense for business, as he often made short trips to photograph new Congressmen and Presidential administrations. He had personal ties to the city, too, since his wife was from Maryland. With the Broadway studio enjoying unprecedented success, Brady seized the opportunity to expand his brand. The new-and-improved National Photographic Art Gallery in Washington opened in April 1858. Brady rented rooms in photographer’s row, a few blocks away from his original location — this time, the studio occupied three floors of a building on Pennsylvania Avenue, between 6th and 7th Streets NW.

As in New York, the main draw of the studio was the gallery space — free to visit and open every day except Sunday. In addition to the usual collection of celebrity portraits, potential clients could see examples of the services available at the studio: mounting and framing, hand coloring with oils and crayons, and Gardner’s enlarged “Imperial” prints. For added amusement, Brady installed a stereoscope display which showed a panoramic view of Niagara Falls.[4] The National Intelligencer reported the space was “perfection,” and that Washingtonians “who have not yet seen this charming gallery would do well to while away an hour in scanning this array of beauty, diplomacy ... and celebrity.”[5]

The actual studio, where the two cameras were set up, occupied the top floor of the space — there, skylights and a “window wall” allowed for the best exposure. Photographers arranged the studio’s collection of furniture and props: chairs, tables, rugs, books, and other decorative items. Some — especially an elaborately-carved chair and a clock always set at 11:52—became trademarks.[6] The finished portraits were captured on negative plates and sent to the development team, who produced prints for the clients. Passersby probably noticed the racks on the roof, where the negatives developed in full sunlight. In fact, appointments were canceled on rainy days.[7]

Brady didn’t spend much time in his new studio after the grand opening. Gardner was in charge of the day-to-day business: organizing appointments, managing staff, keeping the books, and taking some of the photographs. Just as Brady made society connections in New York, Gardner became friends with the many notable Washingtonians who came to sit for him. His relationships with government agents — including future General George McClellan — would benefit him during the war years. But the studio didn’t welcome its most famous guest until 1861. On February 22, staff received a telegram from their boss in New York: “President-Elect Lincoln will visit the gallery on the 24th. Please ready equipment.”[8] Brady had already met and photographed Lincoln during a campaign event in New York, but now his studio would be the first to host the new President. Gardner was understandably nervous about the celebrity appointment, but Lincoln was impressed by his professionalism and skill. In fact, though the portrait circulated under Brady’s name, Gardner was becoming just as well-known in Washington as his boss. It would come to have major consequences for Brady and his studio.

Ironically, the tension between Brady and Gardner escalated as the country also headed towards civil war. Brady began to spend more time in the capital and, consequentially, his studio there. He and Gardner, with their “oversize personalities,” were “not likely to do well together in the confines of a single gallery.”[9] Gardner was used to running the place himself; and during the early months of 1861, he was especially busy. As war became increasingly likely, he predicted that a wave of soldiers, fearing the worst, might come to the studio to have their portraits taken. The new fad in photography was a type of more affordable portraiture known as cartes de visite: small prints, the size of modern business cards, that were cheap to produce. Gardner sensed the business opportunity and purchased special cartes de visite cameras for the Washington studio, allowing photographers to take and produce soldiers’ portraits quickly and efficiently.[10] Brady wasn’t as enthusiastic. An artist at heart, he found the mass production of portraiture “distasteful,” since it “required little skill ... with no opportunity for artistic embellishment.”[11] But Gardner’s instinct proved to be correct: so many soldiers came to the studio that the wait was hours long.[12]

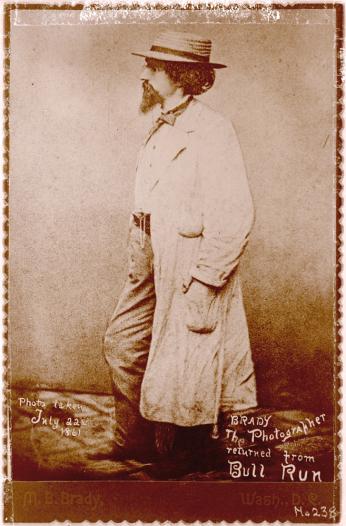

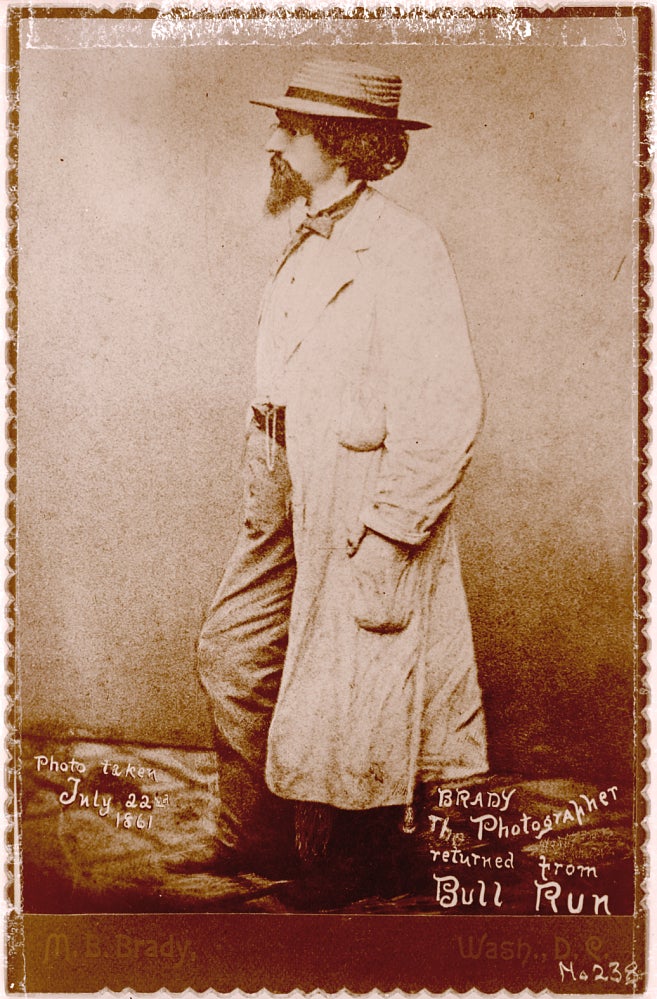

Brady was considering the value of photography in wartime. Beyond capturing the likenesses of men in uniform, photography could document the actual war, allowing the national public to witness it. That summer, when the First Battle of Bull Run broke out, Brady took two wagons to Manassas and photographed the action. Although dangerous, his effort was celebrated in the press. “The public are indebted to Brady,” wrote a columnist in Humphrey’s Journal, “for numerous excellent views of ‘grim-visaged war.’ He has been in Virginia with his camera, and many and spirited are the pictures he has taken.”[13] He was determined to continue this newfound mission.

“My wife and my most conservative friends had looked unfavorably upon this departure from commercial business to pictorial war correspondence,” Brady recounted later, but “I can only describe the destiny that overruled me by saying that…I felt that I had to go.”[14] He organized an army of his own, employing photographers from the Washington studio to accompany and assist him on the road. One of them was Gardner, though he didn’t work directly under Brady anymore. In August 1861, General George McClellan visited the Washington studio and offered Gardner — his old friend — a job: the official photographer for the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers. Brady’s biographer Robert Wilson believes Gardner still worked for Brady during his time with the army, doing “dual service” for both of his employers.[15] It’s hard to tell because all of the images captured by Brady’s staff were actually credited to Brady himself.

There’s no concrete evidence of a feud between Brady and Gardner, but most Civil War historians believe that the rift between them stemmed from Brady’s tendency to promote his own name over the skills of his employees. Thousands of images “photographed by Brady” exist in the Library of Congress and other archives, but historians can’t be sure who took them. Another Brady biographer, Roy Meredith, argues that Brady stayed in Washington and acted as the “director” of operations, following the news and dispatching his staff to nearby battlefields, like Antietam.[16] These photographers acted on their boss’s behalf, so the photos they took were owned by the Brady brand. This became especially evident when Brady published catalog albums of his war photos: none of his staff received any credit. It’s easy to deduce that someone like Gardner, with equal skill and influence, resented this.

Though he never cited any official reason for his decision, by the end of 1862, Gardner had quit the Brady studio.[17] On May 26, 1863, Gardner established himself at a studio at 7th and D Streets NW, only a short distance from his former workplace. Meredith writes that the move “must have been a shock” to Brady, but none of Brady or Gardner’s genuine feelings were ever recorded.[18] Based on Gardner’s further actions, though, it seems that there was little love lost between the two. He took hundreds of negatives from Brady’s studio — portraits and war images that he photographed and considered his property.[19] He hired several of his former colleagues, who quickly abandoned the Brady gallery in favor of Gardner’s new studio. And later that year, one of Brady’s most famous patrons also followed Gardner: Lincoln. Brady was apparently so offended by the betrayal that Lincoln felt obligated to sit for him a few weeks later.[20] Ultimately, though both men often photographed the President, Gardner took the most (and most recognizable) portraits of Lincoln. He also captured many of the most recognizable images of the Civil War. In 1866, he published a two-volume “Photographic Sketchbook” that rivaled Brady’s similar publications. The major difference: Gardner credited every member of his staff, even the developers, throughout the book.

When the Civil War ended in 1865, Brady and Gardner had captured thousands of war images. But in peacetime, sales of their respective photo albums plummeted. No one wanted to be reminded of the horrors of war. As the public moved on from scenes of soldiers and battlefields, the photographers had to return to their studios. The Pennsylvania Avenue studio had never quite recovered after Gardner left. Though his idea to photograph the war had been overwhelmingly successful, Brady spent $10,000 of his own money on the venture — money he never recovered. By 1864, business was so bad he sold 50% of his shares in the Washington gallery, running it with a less-capable partner.[21] Brady constantly petitioned Congress to purchase his war images, knowing they would be of great historic value. Though they did eventually purchase some, they couldn’t save Brady from financial ruin. In 1870, he sold the Washington studio. It operated under the same name until 1881, when it finally closed for good.

Gardner’s popularity also diminished after the war, though he received notable commissions. In the summer of 1865, he was the only photographer present at the execution of the Lincoln assassination conspirators, having been chosen over Brady. In 1867, he was appointed the chief photographer of the Union Pacific Railway. His stereoscopic images, which documented the land through which the railway was built, were later compiled into another album: Across the Continent on the Union Pacific Railway. But by the early 1870s, Gardner had apparently lost interest in his studio — and photography altogether. His obituary in the Washington Post reported that he “left photography” to establish an insurance company, eventually becoming the President of the Equitable Building Association.[22]

Both photographers have been posthumously reunited in Washington. Gardner, a full-time resident of the District, died in 1882 and was buried in Glenwood Cemetery in Northeast. Brady divided his time between Washington and New York, living in hotels and giving interviews to pay his bills. After both of his studios closed, he lived in poverty for the rest of his life. He died in 1895, in the charity ward of a New York hospital. His funeral was actually paid for by veterans, who also funded his burial at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington. He is there next to his wife, marked by a headstone that reports an incorrect year of death.

It's interesting that, despite their separation and supposed feud, Brady and Gardner didn’t thrive after their split. Even today, Alexander Gardner’s accomplishments are overshadowed by the Brady name and enterprise. In 1893, his work became better known thanks to a former assistant, who discovered over 5000 negatives hidden in a Pennsylvania Avenue home.[23]The developed images, which showed famous Civil War politicians and various battlefield scenes, helped shed light on just how prolific Gardner’s Washington career had been. However, even though Gardner doesn’t always get the historic credit he deserves, his former boss suffered without his business skill and savvy. Remembered by history and often called the “father of photojournalism,” Mathew Brady actually died a humble death, having witnessed the collapse of his life’s work. Their golden years were spent together in the Washington studio.

The Penn Quarter area, which Brady and Gardner once knew as “photographer’s row,” looks extremely different today. The building which once housed Brady’s National Photographic Art Gallery is now the headquarters of the National Council of Negro Women. But if you go around the back and look up, you’ll see that the famous “window wall” is still visible on the top floor. Now imagine priceless photos of famous nineteenth-century politicians —s ome of which are on display at the National Portrait Gallery — drying on the roof.

Footnotes

- ^ C. Edwards Lester, “M.B. Brady and the Photographic Art,” in The Photographic Art Journal 1 (New York: W.B. Smith, 1851), 37.

- ^ Robert Wilson, Mathew Brady: Portraits of a Nation (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), 23.

- ^ Josephine Cobb, “Mathew B. Brady’s Photographic Gallery in Washington,” in Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington D.C. 53/56 (Washington: Historical Society of Washington D.C., 1953), 31.

- ^ Cobb, 42.

- ^ The National Intelligencer, June 21, 1858.

- ^ Cobb, 43.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Wilson, 67.

- ^ Wilson, 53.

- ^ Cobb, 47.

- ^ Cobb, 47-48.

- ^ Wilson, 82.

- ^ Humphrey's Journal of the Daguerreotype and Photographic Arts and the Sciences and Arts Pertaining to Heliography 13 (New York: Joseph H. Ladd, 1861-1862), 133.

- ^ Roy Meredith, Mr. Lincoln’s Camera Man: Mathew B. Brady (New York: Dover, 1946), 88; Wilson 111.

- ^ Wilson, 116.

- ^ Meredith, vii.

- ^ Wilson, 147.

- ^ Meredith, 144.

- ^ Wilson, 148.

- ^ Wilson, 169.

- ^ Wilson, 200.

- ^ “ALEXANER GARDNER DEAD: A Prominent Figure in Masonic and Other Circles Passes Away,” The Washington Post, December 11, 1882.

- ^ “War Time Photographs: Negatives for Years Neglected Have Been Discovered,” The Washington Post, 1893.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)