An Assault for Slavery: Preston Brooks Canes Charles Sumner on the Senate Floor

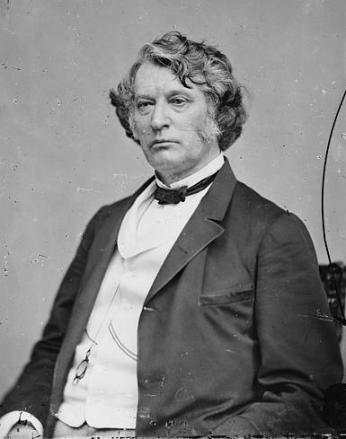

The Senate has adjourned for the day, and the legislators, journalists, and visitors that had filled the chamber file out into the warm evening. Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, a well-known abolitionist, remains at his desk, scribbling notes among his spread of papers. Although he needs glasses, he is not wearing them; he feels they aren’t flattering.

This is partly why he does not recognize the man who approaches him from the aisle. He is well-dressed, with a gentlemanly demeanor, but the smile on his face is tight. He is holding a cane with a knobbed golden head.

He leans over the larger Sumner, still seated, and lowers his voice. He reproaches Sumner for disparaging a relative of his in a speech given several days prior. Sumner still does not know who is speaking to him.

It is May 22, 1856, and as the stranger raises the cane over his head, the nation is about to lurch closer to civil war.

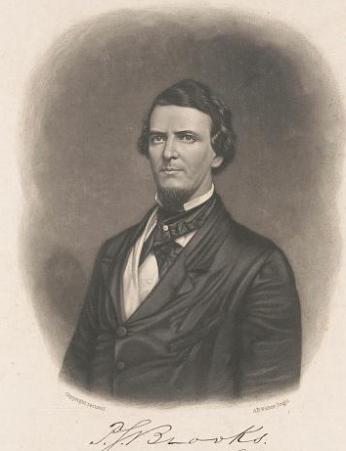

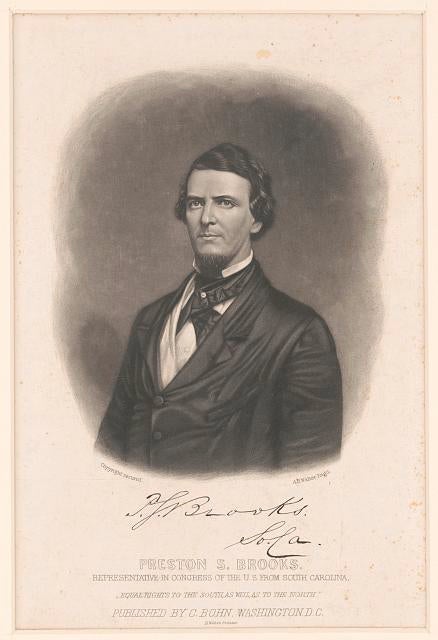

The caning of Charles Sumner by Preston Brooks on the floor of the Senate remains one of the darkest days in the chamber’s history. Sumner had recently given a speech railing against the injustices of slavery and all but accusing Southern lawmakers of depravity. In response, Brooks (a South Carolina Democrat) took it upon himself to avenge his family and Southern honor, unintentionally becoming a cause célèbre for pro-slavery Democrats and secessionists, a role he embraced with pleasure. Though Sumner returned to the Senate for eighteen more years, he never fully recovered from the caning.

Charles Sumner was a man already acquainted with controversy. A lawyer by trade and a radical abolitionist, he had made a name for himself as a “lightning rod for Southern proslavery fury.”1 Sumner had had a singular oratory style—well-researched, elaborate, formal, occasionally biting, and full of educated flourish—and regularly unleashed it on his political opponents.

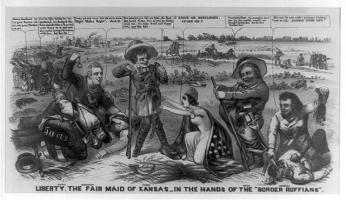

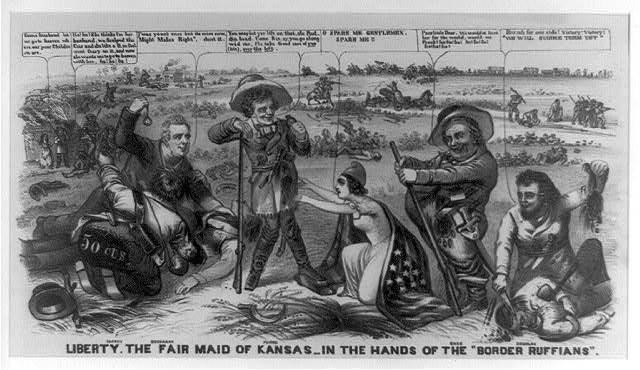

In the 1850s, the pressing issue was slavery. Tensions were tempered but not solutioned by various legislative compromises, the latest and most contentious being the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Initially intended to organize the Nebraska Territory, Southern lawmakers engineered the bill to replace the Missouri Compromise (which would have outlawed slavery in much of the massive Territory) with “popular sovereignty,” in which residents voted on the legality of slavery.2

But because this law did not define what a resident was, violence erupted immediately as pro- and anti-slavery settlers flooded in to cast votes. The events of Bleeding Kansas resulted in dozens of casualties and a fraudulent pro-slavery government elected by thousands of illegally-cast votes.3

Rhetoric throughout Congress grew more heated following the Act’s passage and fallout. Southerners “openly talked of secession” and Northern abolitionists developed “bolder and more radical” condemnations of the South and advocated for emancipation no matter the economic cost to slaveowners.4

Sumner was well-aware of this fraught environment when he stood on March 19 to address his colleagues. Before a full Senate and packed galleries, he gave his “Crime Against Kansas” speech—a “combination legal brief and public discourse” explaining why the Kansas-Nebraska Act was “contrary to both law and… understandings of the limits of slavery.”5

Reciting extensively from memory, Sumner excoriated the main culprits of the “crime,” namely Stephen Douglas of Illinois and Andrew Butler of South Carolina. For two days, he condemned the illegal incursion into Kansas, criticized the political sway of slavery, and relentlessly mocked Douglas and Butler—who had publicly ridiculed him in the past.

Sumner also deployed motifs of sexual imagery in his speech. He accused the South of “the rape of a virgin territory” and Southern senators of sexual immorality with enslaved women.6 Of Butler, making a reference to the insane knight Don Quijote, he said:

“[Butler] believes himself a chivalrous knight with sentiments of honor and courage. Of course he has chosen a mistress… I mean the harlot, slavery. For her, his tongue is always profuse in words.”7

Most damningly, Sumner implied that by breaking the Missouri Compromise, Southern lawmakers—many of them lawyers—were in breach of contract with America. They broke their word and dishonored themselves. Among Southerners, for whom reputation was a person’s “most valuable asset,” this was the gravest of insults.8

The Senate listened, many in shock. During the speech, Stephen Douglas reportedly said to another senator: “This damn fool is going to get himself killed by some other damn fool.”9

He was very nearly right.

Preston Brooks, Representative of Edgefield, South Carolina, was infuriated by Sumner’s personal attacks on Butler, his cousin. As a Southerner, he was compelled to challenge Sumner to a duel, but fellow SC delegate Laurence Keitt dissuaded him. Not only was Sumner, a Northerner, unlikely to agree to such showmanship, but he did not deserve to be dueled as a social equal.

Instead, Brooks intended to physically punish Sumner for his words. The worst he would be charged with was “simple assault and battery.”10

For his weapon, Brooks selected a gutta-percha cane with a gold head and a hollow core. The cane itself was deeply symbolic—men used them to “discipline unruly dogs”—but also practical.11 It would be difficult to wrench out of his hand. Brooks feared that if the larger Sumner disarmed him, he would be forced to draw his pistol and “do that which I would have regretted.”12

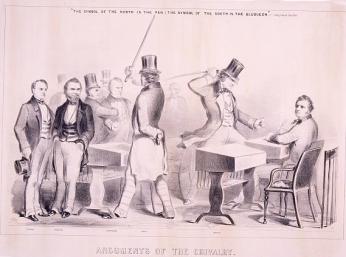

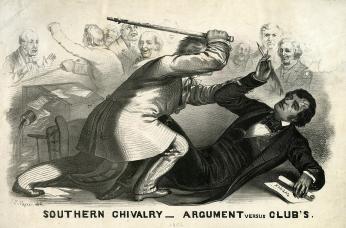

On May 22, Brooks entered the Senate chamber with Keitt and Representative Henry Edmundson of Virginia in tow. Cane in hand, Brooks approached Sumner, who was bent over his desk. To the Senator, he said calmly: "Mr. Sumner… You have libelled my State and slandered my relation, who is aged and absent, and I feel it to be my duty to punish you for it.”13

Before Sumner could speak, Brooks raised his gold-topped cane and brought it down on the Senator’s head.

Almost immediately, Sumter was blinded by his own blood. He struggled to stand, but his desk was bolted to the floor. Brooks delivered a swift and searing flurry of blows with the cane.

Pinned and helpless, Sumner raised his hands to defend himself. Brooks did not stop. Later, he would recount that after his first strike, he “repeated it until I was satisfied. No one interposed.”14

Indeed, Edmundson and Keitt blocked other legislators from intervening.15 Some Southerners stood by of their own accord, crying, “Go it, Brooks,” and “Give the damned Abolitionists hell!”16

By some reports, Sumner freed himself from the desk with a surge of adrenaline, tearing it from its bolts. As the Massachusetts senator “reeled convulsively around the seats,” Brooks pursued him, still hitting him, still unchallenged.17

Brooks’ cane snapped from the force of the strikes, but he continued to beat Sumner with what remained of it. Blood trickled down his face where he had cut himself on a backswing.

Sumner collapsed in the aisle, but Brooks did not stop. Blood had soaked most of Sumner’s coat and shirt, and his shirtsleeves were bloodied from the strikes on his raised arms.

Finally, New York Representatives Ambrose Murray and Edwin Morgan rushed in. As they struggled to restrain Brooks, Senator John Crittenden of Kentucky ran up the aisle shouting, “Don’t kill him!”

Finally pausing, Brooks replied, “I did not intend to kill him, but I did intend to whip him.”18

Keitts and other Southern allies ushered Brooks out of the Senate chamber—not before Crittenden rescued the golden head of Brooks’ snapped cane. Meanwhile, Rep. Morgan supported a bleeding, unconscious Sumner.

The scene left behind was brutal: the chamber floor soaked with blood, Sumner’s desk in disarray. The Senator himself was slumped unconscious on the ground, surrounded by shards of Brooks’ cane. A witness described it as “one of the most cold-blooded, high-handed outrages” in history.19

As Sumner was “bleeding copiously from [his] frightful wounds,” Brooks calmly walked down the steps of the Capitol and out into the city.20

In the street, he met the governor of Missouri. Since Washington would be “full of rumors” in the coming days, he wanted his “friends to understand precisely what I have done, and why I did it.” Brooks had no regrets: he had “punished [Sumner] to my satisfaction.”21

In fact, he would have “forfeited my own self respect” had he not committed the assault.22 Publicly, Brooks always maintained calmly that Sumner “caused the attack, invited the violence, and deserved his beating.”23

In private, though, he was far more enthusiastic about his actions. In a letter to his brother, he wrote, “Every lick went where I intended.”24

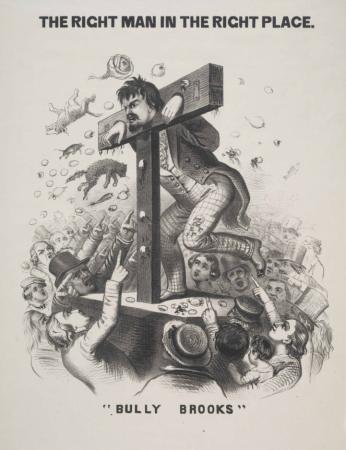

Brooks was arrested shortly afterwards but immediately freed by friends on a $500 bond. When his case saw trial, he was merely slapped on the wrist.

The legal milieu of Washington was “very friendly to” the neighboring South’s honor culture and sympathetic to Brooks’ claim of offense.25 He was fined $300 and served no jail time, partly because the government’s attorney—the son of Francis Scott Key—reviled Sumner and was lax in his prosecution of Brooks.

In Congress, Brooks also avoided real consequences. The Senate ruled it had no right to punish a non-member. A House motion to expel Brooks and censure Keitts gained a majority but not the necessary two-thirds of votes. In a show of conciliation, both resigned anyway.

But the gesture really was just that—gesture. Both were “assured of reelection” in districts that overwhelmingly approved of their actions.26

In the South, “combined glee and righteousness” swept constituents and politicians alike, as gifts—especially sturdier canes—flooded into Brooks’ office.27 Southern Senators wore shards of Brooks’ cane on chains around their necks; Brooks bragged that they were “as sacred relics.”28 At a DC rally in Brooks’ support, a banner advanced amidst the crowd, reading: “Sumner and Kansas: Let Them Bleed.”29

Convalescing at home, Sumner received letters of “sympathy, anger, shock, and indignation” even from those who did not agree with his political provocations.30 He suffered head trauma, an infection and fever, and likely developed post-traumatic stress disorder.31 Meanwhile, Democrats and Southerners accused him of feigning his injuries and taunted him for cowardice when he did not return to the Senate for months.

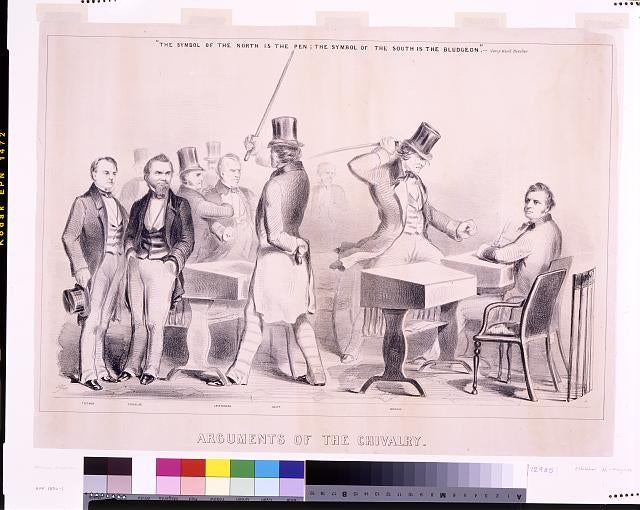

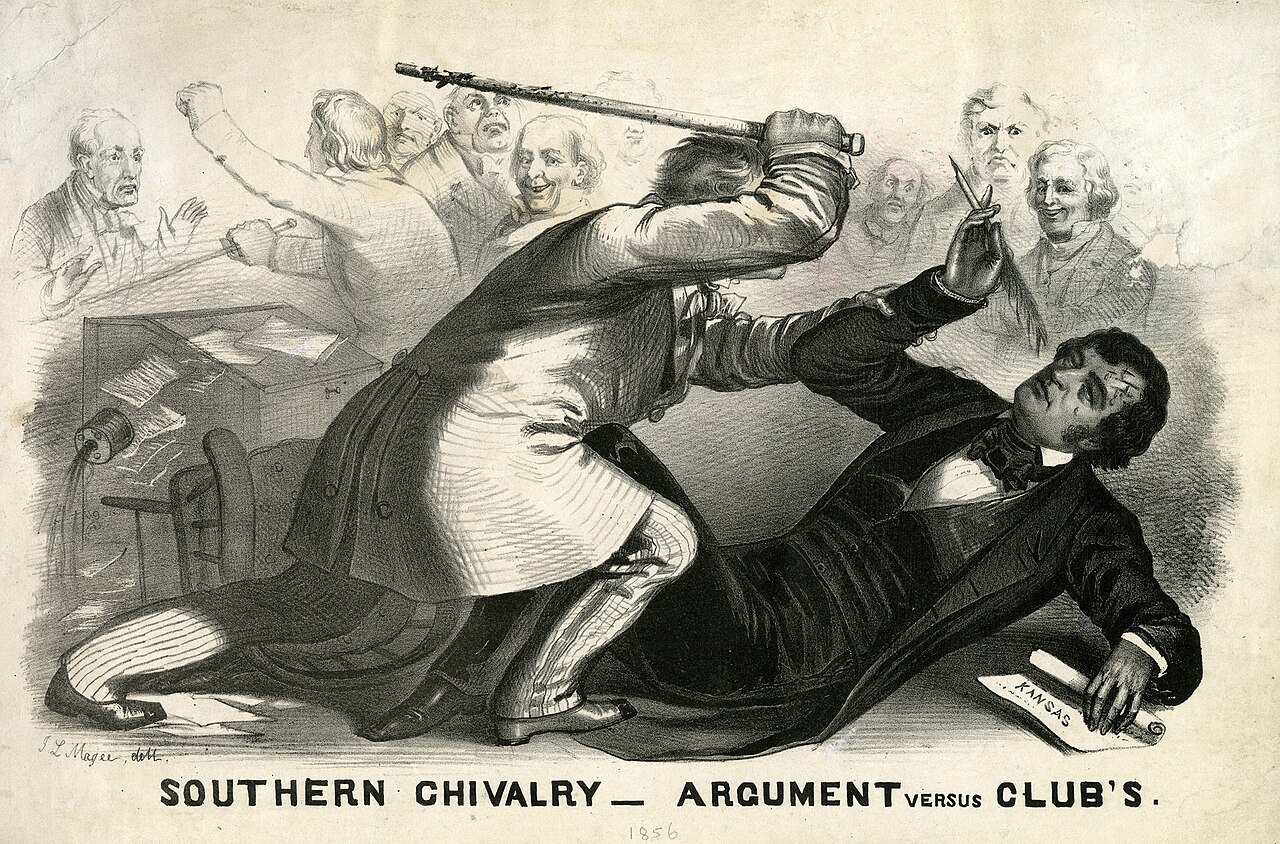

The rest of the country followed the story as newsrooms across America erupted in clamor. Both sides of the press called for violence: Southern papers proposed that the attack modeled a novel solution for dealing with abolitionists, while Northern journalists suggested revenge on Brooks.

Papers sympathetic to Sumner recounted the “gross attack” and disparaged Brooks for “outrival[ing]” the violent pro-slavery settlers in Kansas.32 They analogued Brooks’ attack on Sumner to the South’s aim to bully anti-slavery advocates into silence. The New York Evening Post asked its readers: “Are we to be chastised as they chastise their slaves? Are we too, slaves… when we do not comport ourselves to please them?”33

Conversely, pro-slavery writers were quick to characterize Brooks’ “coolness and courage” compared to the “craven-hearted wretch from Massachusetts.”34 They praised him for his “most glorious deed” and recommended a “double dose” of “thrashing” as a “remedy” for abolitionist views.35

Democrat-aligned papers reprinted reports of Sumner’s alleged fake illness and called for him and other abolitionists to be “punished… hung or put in the penitentiary.”36 Some even stressed the event as evidence that the South should consider leaving the Union.

A spare few took a more moderate stance. Some journalists were dismayed that the “sanctity” of Congress had been violated.37 Others felt that Sumner and Brooks were both (but not equally) in the wrong, one for his words, the other for his actions, and that the deterioration of civil debate was increasingly unworkable and venomous. If Brooks was “a hot-blooded bully,” then Sumner was “an educated ruffian in cold blood.”38

The Louisville Journal was particularly prescient. It pained the authors to see “a very great portion of the press” writing “to excite to a still greater degree of fury the mad fanaticism that is driving the Union into imminent danger of speedy dissolution.”39

Only four years later, divisions over slavery would spark the Civil War.

The brutal assault on Charles Sumner contributed to the breakdown of civil discussion in Congress and further polarization between pro- and anti-slavery legislators and citizens. It radicalized moderate Northerners to the abolitionist view that “proslavery Southerners—stripped of their gentlemanly finery and veneer of cloying politeness—were little more than savages.”40 It also put the nascent Republican party on the ascent. In only four years, the party would elect their first president: Abraham Lincoln, who would make Sumner’s dreams of abolition a reality.

Footnotes

- 1

Hoffer, William James Hull. The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor, Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War. JHU Press, 2010. https://archive.org/details/caningofcharless0000hoff.

- 2

Senate Historical Office. “U.S. Senate: The Kansas-Nebraska Act.” United States Senate. Accessed March 16, 2025. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/Kansas_Nebraska_Act.htm.

- 3

Howard, William A.; Sherman, John; Oliver, Mordecai (1856). Report of the Special Committee Appointed to Investigate the Troubles in Kansas (Report). Washington, DC: United States House of Representatives. https://www.loc.gov/item/rc01000093/

- 4

Puleo, Stephen. The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War. Westholme Pub Llc, 2013. https://archive.org/details/caningassaulttha0000pule.

- 5

Hoffer, William James Hull. The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor, Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War. JHU Press, 2010. https://archive.org/details/caningofcharless0000hoff.

- 6

Hoffer, William James Hull. The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor, Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War. JHU Press, 2010. https://archive.org/details/caningofcharless0000hoff.

- 7

Storey, Moorfield (1900). American Statesmen: Charles Sumner. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 139–140

- 8

Hoffer, William James.

- 9

Walther, Eric H. (2004). The Shattering of the Union: America in the 1850s. Lanham, Maryland: SR Books. p. 97

- 10

Puelo, Stephen.

- 11

Senate Historical Office. “U.S. Senate: The Caning of Senator Charles Sumner.” United States Senate. Accessed March 15, 2025. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/The_Caning_of_Senator_Charles_Sumner.htm.

- 12

Puelo, Stephen.

- 13

Testimony on the Assault of Senator Charles Sumner; 1856; Records of Early Select Committees, 1793–1909; Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, Record Group 233; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/testimony-on-the-assault-of-senator-charles-sumner, March 15, 2025]

- 14

Testimony on the Assault of Senator Charles Sumner; 1856; Records of Early Select Committees, 1793–1909; Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, Record Group 233; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/testimony-on-the-assault-of-senator-charles-sumner, March 15, 2025]

- 15

Puelo, Stephen.

- 16

Hoffer, William James.

- 17

Puelo, Stephen.

- 18

Puelo, Stephen.

- 19

Puelo, Stephen.

- 20

Puelo, Stephen.

- 21

Testimony on the Assault of Senator Charles Sumner; 1856; Records of Early Select Committees, 1793–1909; Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, Record Group 233; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/testimony-on-the-assault-of-senator-charles-sumner, March 15, 2025]

- 22

Puelo, Stephen.

- 23

Hoffer, William James.

- 24

Hoffer, William James.

- 25

Hoffer, William James.

- 26

Hoffer, William James.

- 27

Puelo, Stephen.

- 28

Puelo, Stephen.

- 29

Puelo, Stephen.

- 30

Puelo, Stephen.

- 31

Thomas G. Mitchell, Anti-slavery politics in antebellum and Civil War America (2007) p. 95

- 32

Carroll free press. [volume] (Carrollton [Ohio]), 05 June 1856. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83035366/1856-06-05/ed-1/seq-1/>

- 33

Gienapp, William E. (1988). The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852–1856. Oxford University Press. p. 359.

- 34

The New York herald. [volume] (New York [N.Y.]), 11 June 1856. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030313/1856-06-11/ed-1/seq-4/>

- 35

Various, “Southern Newspapers Praise the Attack on Charles Sumner,” SHEC: Resources for Teachers, accessed March 4, 2025, https://shec.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/1548.

- 36

The New York herald. [volume] (New York [N.Y.]), 11 June 1856. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030313/1856-06-11/ed-1/seq-4/>

- 37

Puelo, Stephen.

- 38

The star of the north. [volume] (Bloomsburg, Pa.), 11 June 1856. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025182/1856-06-11/ed-1/seq-2/>

- 39

The New York herald. [volume] (New York [N.Y.]), 11 June 1856. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030313/1856-06-11/ed-1/seq-4/>

- 40

Puelo, Stephen.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)