A General, a Queen, and the President

“The noblest art is that of making others happy” — P.T. Barnum

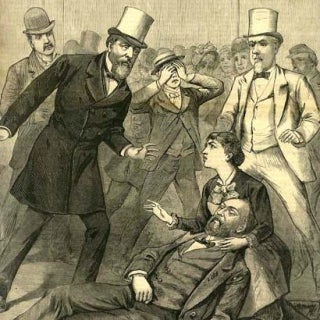

February of 1863 saw one of the most anticipated celebrity weddings of its time—after all, what better to provide a momentary distraction from the realities of the Civil War than a little star gossip? The bride and groom were General Tom Thumb (Charles Stratton) and the Queen of Beauty Lavinia Warren, of P.T. Barnum’s American Museum (which would later become Barnum’s Circus) in New York City. At 12:30 p.m. on February 10, 1863 in Manhattan’s Grace Episcopal Church, Tom and Lavinia wed in the presence of an enormous crowd, which spilled out onto Broadway and for many more miles into the City, thanks to Barnum’s extensive publicizing of the event.[1]

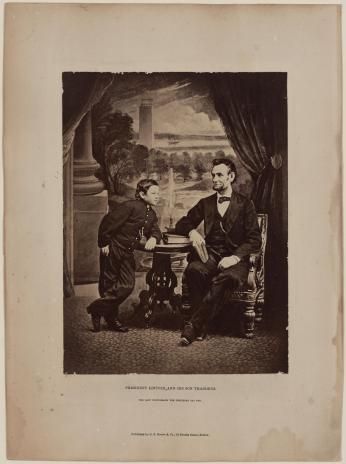

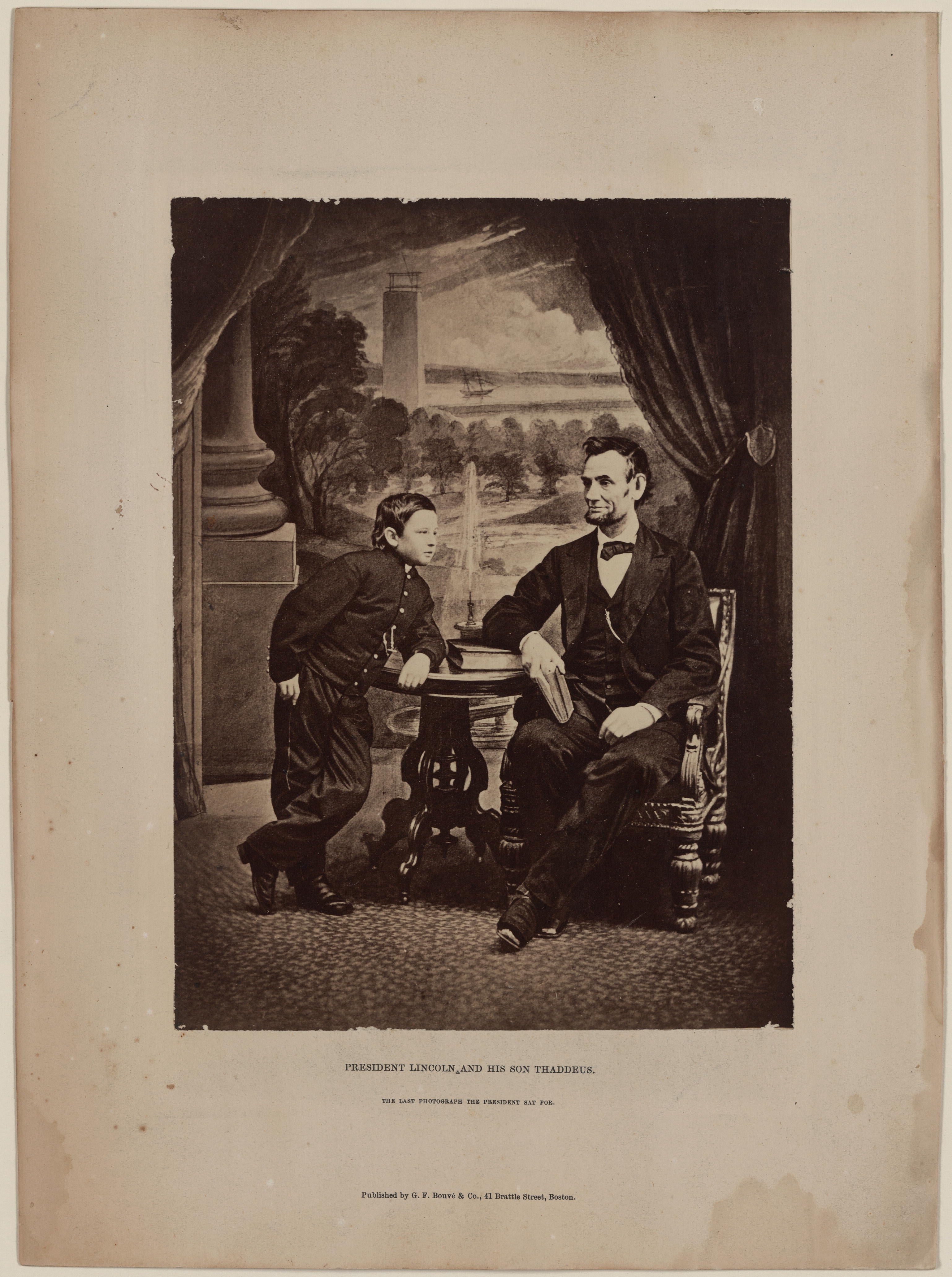

The more than 2,000 invited wedding guests appeared to be a who’s who of American nobility, including a number of congressmen and high-ranking generals, in addition to the thousands of average New Yorkers who showed up hoping to catch a glimpse of the famous tiny couple. The New York Times even described the population of New York that day as “those who did and those who did not attend the wedding.”[2] People across America were fascinated by Barnum’s Tom Thumb and the President of the United States was no exception. The Lincolns were so enthralled by Barnum’s acts that they invited the newlywed Strattons to the White House for a wedding reception just a few days later.

So after their extravagant wedding and party hosted by Barnum at the Metropolitan Hotel in Manhattan, the couple traveled to the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C. arriving on February 12. That evening, much to the excitement of local guests, the couple attended a hop in the hotel ballroom from 10 to 11 p.m. which included dancing and music provided by Goodall’s 10-piece capital band.[3]

The next day, Friday, February 13, 1863 the Strattons arrived at the White House for an exclusive 8 p.m. party hosted by President and Mrs. Lincoln—an event that, in addition to the Lincolns’ infatuation with the Thumbs, was undoubtedly arranged as a consequence of P.T. Barnum’s loyal Republican status.[4] The Lincolns sent out limited invitations to the party, which was viewed as tomfoolery to some within their stiffer social and political circles.[5] Even Lincoln’s eldest son Robert felt that hosting the Thumbs at the White House was an embarrassing triviality, though he did end up attending the party.[6]

Among the excited guests in the Executive Mansion that evening were Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, Union General Benjamin Butler, and Sara Jane Lippincott, better known by her pen name Grace Greenwood— an author and one of the first female journalists to gain access to the Congressional press galleries.[7] In a later reflective piece on Lincoln, Greenwood wrote a detailed account of the evening, including the moment that a 2 foot 10 inch Tom Thumb shook hands with the 6 foot 4 inch President Lincoln:[8]

“The reception took place in the East room; and when, following the loud announcement, ‘Mr. and Mrs. Charles Stratton,’ the guests of honor entered from the corridor and walked slowly up the long salon, to where Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln stood, to welcome them, the scene became interesting, though a little bizarre. The pigmy ‘General,’ at that time still rather good-looking, though slightly blasé, wore his elegant wedding suit, and his wife, a plump but symmetrical little woman, with a bright, intelligent face, her wedding dress—the regulation white satin, with point lace, orange blossoms and pearls—while a train some two yards long swept out behind her.

I well remember the ‘pigeon-like stateliness’ with which they advanced, almost to the feet of the President, and the profound respect with which they looked up, up, to his kindly face. It was pleasant to see their tall host bend, and bend, to take their little hands in his great palm, holding Madame’s with especial chariness, as though it were a robin’s egg, and he were fearful of breaking it. Yet he did not talk down to them, but made them feel from the first as though he regarded them as real ‘folks,’ sensible, and knowing a good deal of the world. He presented them, very courteously and soberly, to Mrs. Lincoln, and in his compliments and congratulations there was not the slightest touch of exaggeration which a lesser man might have been tempted to make use of, for the quiet amusement of on-lookers; in fact, nothing to reveal to that shrewd little pair his keen sense of the incongruity of the scene.” [9]

Mrs. Lavinia Stratton herself also looked back on her evening at the White House fondly, and gave a detailed account of her personal interactions with the Lincolns in her autobiography:

“Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln received us cordially. When Mr. Lincoln stooped his towering form to greet us, there was a peculiarly quizzical expression in his eye, which almost made me laugh outright. Knowing his predilection for story telling, I imagined he was about to utter something of a humorous nature; but he only said, with a genial smile, ‘Mrs. Stratton, I wish you much happiness in your union.’ After receiving the congratulations of all present, the President took our hands and led us to the sofa, lifting the General up and placing him at his left hand, while Mrs. Lincoln did the same service for me, placing me at her right. We were thus seated between them.” [10]

Lavinia goes on to mention that the Lincolns’ younger son, Tad, accompanied his parents at the party, and at one point during conversation, asked his mother if she thought it was funny that his father was so tall, while the Strattons were so little. “The President, overhearing the remark, replied, ‘My boy, it is because Dame Nature sometimes delights in doing funny things. You need not seek for any other reason; for here you have the short and the long of it,’ pointing to the General [Stratton] and himself. This created quite a laugh.”[11]

Indeed it appears that in addition to refreshments of cake, wine, and ices, the night was filled with humor and solace. Greenwood recounted:

“Later, while the bride and groom were taking a quiet promenade by themselves up and down the big drawing room, I noticed the President gazing after them with a smile of quaint humor; but in his beautiful, sorrow-shadowed eyes, there was something more than amusement—a gentle, human sympathy in the apparent happiness and good-fellowship of this curious wedded pair—come to him out of fairyland.” [12]

Around 9:30 p.m., the Strattons left the White House and returned to the Willard where they attended a second reception in the hotel’s ballroom for another hour and a half.[13] The next morning, before departing the District, the couple received a pass and permit from the President allowing them to cross the Long Bridge over the Potomac and visit the Army Camp in Arlington Heights, where the 40th Massachusetts Regiment, of which Lavinia’s brother Benjamin was a part, was passing through on its return from the war front.[14] Lavinia spoke of their reception upon that visit:

“As we rode through the vast camp, we were greeted with cheers, throwing up of caps, and shouts from all sides, such as, ‘General, I saw you last down in Maine!’ – ‘I saw you in Boston!’ – ‘I saw you in Pennsylvania!’ – ‘I saw you in old New York!’ – ‘Three cheers for General Tom Thumb and his little wife!’ etc. It seemed a joy to them to see a face which recalled to their minds’ memories of happy days at home. It was a grand but a sad sight to me. I reflected how many of those brave fellows would perhaps never again see home, wives, or children, but their bodies now so full of life be lying inanimate on the battle field.” [15]

Lavinia’s reflection on their visit to the Union camp is a poignant one, as it also speaks to the unusual nature of their White House wedding reception. While some of Lincoln’s counterparts might have viewed this party as something of a pop culture charade, Lincoln himself appeared to think nothing of the sort, showing that these small moments of humor and hope were crucial in allowing him, and the Union, to overcome a dark moment in American history.

Footnotes

- ^ “THE LOVING LILLIPUTIANS: WARREN-THUMBIANA. Marriage of General Tom Thumb and the Queen of Beauty.” New York Times. February 11, 1863. http://search.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/docview/91714849/abstract/24….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “The Hop at the Willards: Presence of the Distinguished Lilliputians.” Evening Star, February 13, 1863. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/page/v2%3A13D5DA85A….

- ^ Greenwood, Grace. Abraham Lincoln: Tributes from His Associates, Reminiscences of Soldiers, Statesmen and Citizens. T.Y. Crowell, 1895. 108-113.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “That One Time Abraham Lincoln Threw a Wedding Reception for Tom Thumb,” August 13, 2011. https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/28504/one-time-abraham-lincoln-thre…; Greenwood, Grace. Abraham Lincoln: Tributes from His Associates, Reminiscences of Soldiers, Statesmen and Citizens. T.Y. Crowell, 1895. 108-113.

- ^ Greenwood, Grace. Abraham Lincoln: Tributes from His Associates, Reminiscences of Soldiers, Statesmen and Citizens. T.Y. Crowell, 1895. 108-113.

- ^ Nilsson, Jeff. “General Tom Thumb Gets Married | The Saturday Evening Post.” The Saturday Evening Post, February 9, 2013. https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2013/02/general-tom-thumb-marries-l….

- ^ Greenwood, Grace. Abraham Lincoln: Tributes from His Associates, Reminiscences of Soldiers, Statesmen and Citizens. T.Y. Crowell, 1895. 108-113.

- ^ Warren, Lavinia. “Some Recollections: The Story of My Marriage and Honeymoon from Mrs. Tom Thumb’s Autobiography.” New York Tribune Sunday Magazine, October 7, 1906. https://www.disabilitymuseum.org/dhm/lib/detail.html?id=1131&page=all.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Greenwood, Grace. Abraham Lincoln: Tributes from His Associates, Reminiscences of Soldiers, Statesmen and Citizens. T.Y. Crowell, 1895. 108-113.

- ^ “Movements of Gen. Tom Thumb and Lady.” Evening Star, February 14, 1863. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2%3A13D5DA85AE05A3….

- ^ Warren, Lavinia. “Some Recollections: The Story of My Marriage and Honeymoon from Mrs. Tom Thumb’s Autobiography.” New York Tribune Sunday Magazine, October 7, 1906. https://www.disabilitymuseum.org/dhm/lib/detail.html?id=1131&page=all.

- ^ Ibid.

![Brady, Mathew B., Approximately, photographer. The Fairy Wedding group / From photographic negative in Brady's National Portrait Gallery, from photographic negative by Brady., 1863. [New York: E. & H.T. Anthony, 501 Broadway] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017659631/. Brady, Mathew B., Approximately, photographer. The Fairy Wedding group / From photographic negative in Brady's National Portrait Gallery, from photographic negative by Brady., 1863. [New York: E. & H.T. Anthony, 501 Broadway] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017659631/.](/sites/default/files/styles/embed/public/The_Fairy_Wedding_group_-_From_photographic_negative_in_Brady%27s_National_Portrait_Gallery%2C_from_photographic_n.jpg?itok=-35HUT-4)

![Brady, Mathew B., Approximately, photographer. The Fairy Wedding group / From photographic negative in Brady's National Portrait Gallery, from photographic negative by Brady., 1863. [New York: E. & H.T. Anthony, 501 Broadway] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017659631/. Brady, Mathew B., Approximately, photographer. The Fairy Wedding group / From photographic negative in Brady's National Portrait Gallery, from photographic negative by Brady., 1863. [New York: E. & H.T. Anthony, 501 Broadway] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017659631/.](/sites/default/files/The_Fairy_Wedding_group_-_From_photographic_negative_in_Brady%27s_National_Portrait_Gallery%2C_from_photographic_n.jpg)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)