The Witnesses

What do a five-year-old boy, a woman working at a train station and an African American newspaperman have in common? Samuel J. Seymour, Sarah V. E. White and Samuel H. Hatton were little-known Washingtonian witnesses to some of the most influential murders in history: those of U.S. Presidents.

Presidential assassination is a topic we’ve touched on before: after all, two of the four murders happened here in the capital. Perhaps most salient in the popular imagination was the shooting of Abraham Lincoln, when John Wilkes Booth leapt off the balcony into the stage at Ford’s Theatre, crying “Sic semper tyrannis!” with a smoking pistol in hand. On this blog, we’ve talked about Lincoln’s guests to the theatre that fateful night, Clara Harris and Henry Rathbone, and have even discussed another murder conspiracy that took place that same day.

James Garfield’s murder tends to receive less press, but we have discussed it briefly in light of its impact on the downfall of a railroad station that was once on the National Mall. President Garfield’s demise came when Charles Guiteau shot him twice in the aforementioned train station. Unlike Lincoln, Garfield died a rather slow death: many posit that his bullet wounds would not have been fatal were it not for malpractice by doctors: Garfield died of infection two months after being shot.[1]

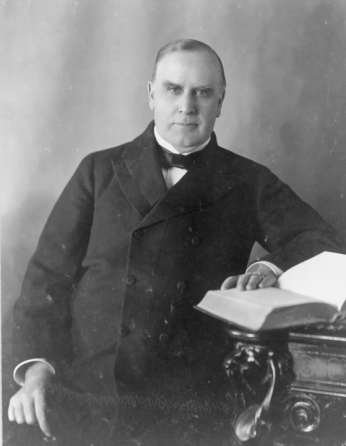

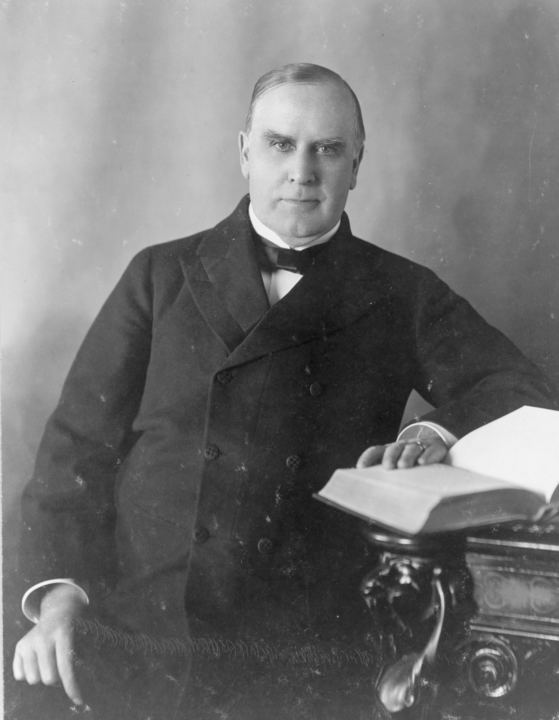

While William McKinley’s assassination took place at the 1901 Pan American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, keep reading for an interesting local connection. So, without further ado, this article will introduce and evaluate the stories of three witnesses to presidential shootings.

Samuel J. Seymour

By 1956, three presidents had been shot, but it had been half a century since the most recent assassination. So, a man named Samuel Seymour caused quite the sensation when he publicly declared that he had witnessed President Lincoln’s assassination in 1865.

At the age of 93, he authored an article for the Milwaukee Sentinel, entitled “I Saw Lincoln Shot,” telling the story of when he was five years old on a visit to Washington from his home in Talbot County, Maryland.[2] That fateful April day, his nurse, Sarah Cook and the wife of his father’s employer, Mrs. Goldsboro, took “Sammy” to go see Our American Cousin.

As Seymour put it:

“[President Lincoln] was a tall, stern-looking man. I guess I just thought he looked stern because of his whiskers, because he was smiling and waving to the crowd. When everyone sat down again and the actors started moving and talking, I began to get over the scared feeling I’d had ever since we arrived in Washington. But that was something I never should have done. All of a sudden a shot rang out—a shot that will always be remembered—and someone in the President’s box screamed. I saw Lincoln slumped forward in his seat. People started milling around and I thought there’d been another accident when one man seemed to tumble over the balcony rail and land on the stage. ‘Hurry, hurry, let’s go help the poor man who fell down,’ I begged. But by that time John Wilkes Booth, the assassin, had picked himself up and was running for dear life … That night I was shot 50 times, at least, in my dreams—and I sometimes still relive the horror of Lincoln’s assassination, dozing in my rocker as an old codger like me is bound to do.”[3]

Two years after publishing this newspaper article, Seymour appeared on a game show called “I’ve Got a Secret,” where contestants were challenged to guess a hidden fact about the guest. When one contestant figured out that the secret concerned Abraham Lincoln, she asked: “Was this a pleasant thing?” In reply he said: “Not very pleasant, I don’t think. I was scared to death.”[4]

While Seymour’s account is often taken at face-value, it is difficult to substantiate with any evidence other than his word. After all, his description is general enough that anyone with a basic knowledge of Lincoln’s murder could have made it up. There were 2,000 people attending the play at Ford’s Theatre, but there is no documentation of whether Sarah Good or Mrs. Goldsborough were among those. There is also no way to prove whether Samuel and the two women were sitting in the box across from Lincoln because Ford’s Theatre had open seating on each level.[5]

Nonetheless, there is nothing that conclusively disproves Seymour’s story, so his first-hand account opens up an interesting perspective toward the killing of our sixteenth president.

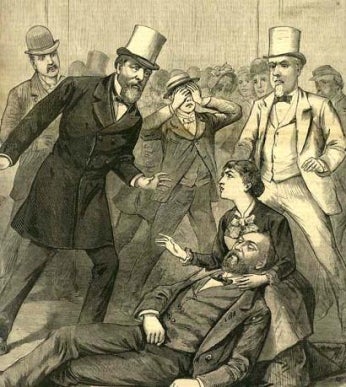

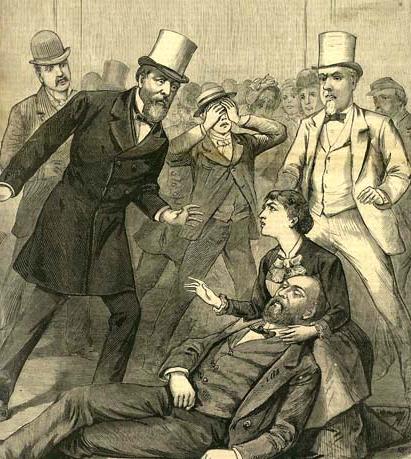

Sarah V. E. White

On July 2, 1881, President James Garfield was preparing to celebrate Independence Day in New England. He arrived at the Sixth Street station of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad with his wife and a small party of fellow travelers. Secretary of State James Blaine accompanied the president to the station to see him off. After the rest of the party were seated in the train, President Garfield and Blaine were about to part ways. While walking arm-in-arm through the ladies’ waiting room, a forty-year-old named Charles Guiteau approached them from behind and fired two shots.[6] After shooting, he allegedly said: “I am a Stalwart and [Vice President] Arthur is now president.”[7]

Interestingly, as the assassination happened in a place designated for women, it was witnessed by “some fifty or sixty ladies,” according to The Sun.[8] Local publications gave voice to one female witness of the crime, by the name of Sarah White: an employee at the railroad station, in charge of the waiting room.

Here’s what she said to journalists at the Washington Post:

“I was almost the only one in the room after the first shot was fired, and I saw the whole of it. The man that shot the President came in the door from the large waiting-room at the same time the President entered from the B-street door. The President turned past the row of seats and that made his back come toward the man, who was about five feet away. The man fired and that must have been the shot that struck the arm, for the President paid no attention to it or the man. He then fired a second time, and almost immediately the President fell right by the second row of seats. I hurried up to him and lifted up his head. Janitor Smith came right afterwards, rushed out to call the police and then came back. He assisted to raise the President up. He vomited some, and then spoke, I think it was to his son, they said that it was. He said nothing to the man that did the shooting. When they lifted him on the mattress he groaned. The man that fired the pistol walked into the main hall. I have seen him here before, I think, two or three times.”[9]

Little else is known about Sarah White, but in all likelihood she was a very credible witness, as she was interviewed immediately in the aftermath of the shooting. It is even possible that she was covered in President Garfield’s blood while she was being interviewed: as remarked in the Evening Star, “The floor was covered with the President’s blood. A number of people who were around shortly afterwards have some of that blood on their person.”[10] Three months later (and after Garfield’s death on September 19, 1881), White’s name was included on a list of witnesses who would be summoned by the government to testify in Guiteau’s murder trial.[11]

Samuel H. Hatton

Our last witness, Samuel Hatton, shares some similarities with Samuel Seymour: he was also born in the 1860s, and had a newspaper article published late in life discussing what he saw. But, Hatton stands apart in one crucial way: he was present for not one, but two presidential assassinations.

The Baltimore Afro-American published a segment called “Washingtonians You Should Know,” which highlighted Hatton in November of 1940. By way of introduction, the author writes:

“Many interesting stories of American life during the past half-century could be told by Samuel H. Hatton, former muleteer, medicine showman, steel-worker, newspaperman, and witness to the assassination of two Presidents. Born in Washington in 1868, young Hatton was bitten by the wander-bug at an early age. Shortly after his twelfth birthday, he ran away from home and obtained a job driving a mule team along the banks of the historic old Chesapeake and Ohio Canal.”[12]

It later goes on to claim:

“He was not more than fifteen or twenty yards distant when an assassin’s bullet cut down President McKinley; he was present at the old Sixth Street Depot when President Garfield was shot; He was the only person of his race present when President Theodore Roosevelt took the oath of office at the Wilcox home following the death of President McKinley.”[13]

Like in the case of Samuel Seymour, it is difficult to completely fact-check Hatton’s claims. As he died in 1950 at the age of 82,[14] he would have been 13 years old when Garfield was assassinated, and 33 years old at the shooting of McKinley. While Hatton was not included in the Evening Star’s 1881 list of witnesses, it is possible that his age and race would have discounted him as a credible witness to authorities. Also, it is noteworthy that the newspaper article does not say that Hatton saw Guiteau shoot Garfield, but that he was “present” at the train station when it happened.

In regard to McKinley’s shooting, Hatton was in Buffalo during the Pan American Exposition on assignment by the Treasury Department as a special messenger who would count silver bullion.[15] When President McKinley was shot by Leon Czolgosz, it was a sweltering September day around 4:00 PM. The President was hosting a meet-and-greet in the Temple of Music, where a long line of people trailed to shake hands with him. If Samuel Hatton was in line to meet the President, he would have likely been behind 30-40 people, given his distance of 15-20 yards.

The stories of Seymour, White and Hatton prove that witnesses to presidential shootings were diverse. Undoubtedly, there were countless other spectators whose stories remained in the privacy of their memories and families. These first-hand accounts bring American legends to life, reminding us that these assassinations impacted more than just politics.

Footnotes

- ^ Kenneth D. Ackerman, “The Garfield Assassination Altered American History, But Is Woefully Forgotten Today.” Smithsonian Magazine, March 2, 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/garfield-assassination-altered-american-history-woefully-forgotten-today-180968319/.

- ^ Colin Schultz, “1950s Game Show Guest Had a Secret: He Saw Lincoln’s Assassination.” Smithsonian Magazine, Smart News, Oct 19, 2012, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/1950s-game-show-guest-had-a-secret-he-saw-lincolns-assassination-82077477/#:~:text=A%205%2Dyear%20old%20Samuel,on%20a%201956%20game%20show.

- ^ Samuel J Seymour, “I Saw Lincoln Shot,” Milwaukee Sentinel. Found on HistoryFlicks4u, “Last Witness to President Abraham Lincoln Assassination I’ve Got A Secret.” Youtube, Video, (4:59-7:17), Mar 10, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1RPoymt3Jx4&feature=emb_title&ab_channel=HistoryFlicks4u.

- ^ HistoryFlicks4u, “Last Witness to President Abraham Lincoln Assassination I’ve Got A Secret.” Youtube, Video, (3:43), Mar 10, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1RPoymt3Jx4&feature=emb_title&ab_channel=HistoryFlicks4u.

- ^ “I’ve Got a Secret: Evaluating Historic Truth,” https://www.fords.org/blog/post/i-ve-got-a-secret-evaluating-historic-truth/.

- ^ Evening Star (Washington (DC), District of Columbia), July 2, 1881: 1. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A13D5DA85AE05A305%40EANX-13E5532112B75608%402408264-13E45E0FC1523220%400.

- ^ Kenneth D. Ackerman, “The Garfield Assassination Altered American History.”

- ^ "First Accounts of the Attempted Assassination: THE SCENE OF THE TRAGEDY." The Sun (1837-1994), Jul 03, 1881. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/534562450?accountid=46320.

- ^ "WHAT GUITEAU TOLD A DETECTIVE: GEORGE W. MCELFRCSH THROWS SOME LIGHT ON THE ASSASSIN'S MOTIVES." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jul 03, 1881. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/137846992?ac….

- ^ Evening Star, July 2, 1881.

- ^ Evening Star (Washington (DC), District of Columbia), October 12, 1881: 4. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A13D5DA85AE05A305%40EANX-NB-13E6021A3017F748%402408366-13E5FD4EB37B4688%403-13E5FD4EB37B4688%40.

- ^ Joe Shepherd, “Washingtonians You Should Know.” Afro-American. ProQuest Historical Newspapers, Nov 23, 1940, https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/hnpbaltimoreafricana….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress, May 16 1950, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1950-05-19/ed-1/seq-22/.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)