Bread Kneaded on Capitol Hill

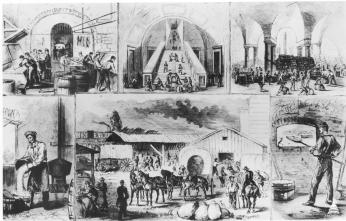

As congressmen convened for a special session in July 1861, they were welcomed into the Capitol by the smell of baking bread. Just months into the Civil War, the building had already seen thousands of troops pass through its doors, and now it was the site of one of the largest bakeries the world had ever known. Twenty ovens, each with the capacity of holding hundreds of loaves of bread, were housed in the basement, and multitudes of men spent hours tending yeast and kneading dough.[1] Having been in recess for less than four months, the congressmen were astounded, and some even annoyed, with this new mammoth bakery occupying their space. But a lot had changed for the country – and for the Capitol – in that short period of time.

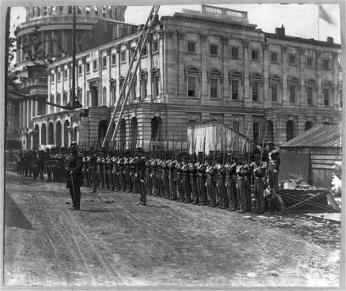

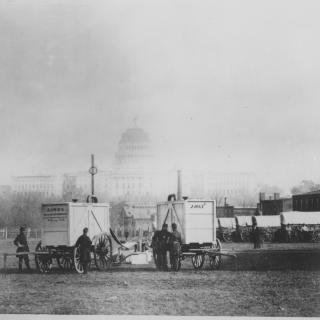

When the war broke out in April, fears of a Confederate take-over abounded in Washington. The relatively small city of about 65,000 worried about its security as the Union’s capital and the stability of the North as a whole. On April 15, President Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 militiamen to perform a 90-day service for the defense of the Union.[1] By April 19, they were pouring into Washington. But the city lacked the sufficient resources needed to lodge and feed this influx of troops... Enter the Capitol.

With Congress not in session, troops from Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New York decided to take over its building. The Capitol was still a work in progress in 1861 and was at the tail end of an extensive renovation project. Head architect Thomas U. Walter was thus unhappy to find soldiers lodging in his office, with upwards of 6,000 elsewhere. “The Capitol is to be turned into a barracks,” he wrote in May. “The noise and the tumult, and the music and the pipe smoke daily interfere with my personal comfort… [And] the smell is awful… Every hole and corner is defiled.”[2] Troops were housed everywhere from the new Senate chamber to the Rotunda. It is rumored that men from the 11th New York Infantry even entertained themselves by swinging on ropes from the cornice of the unfinished dome.[3] But though these soldiers were billeted “in the most magnificent quarters in the world,” feeding them was a problem.[4]

As the Sixth Massachusetts grumbled about being ill-fed, Lieutenant Thomas J. Cate headlined the construction of two ovens to feed the hungry troops. But demand quickly outpaced the supply of Cate’s small operation, and more ovens were built. By mid-May, the bakery was capable of turning out 10,000 rations of bread a day, enough to feed the soldiers housed at the Capitol and then some.[5] The Government seized flour from a factory in Georgetown for the use of the bakery and almost 100 carts and wagons were employed in the transport of both flour to the Capitol and bread to the troops quartered elsewhere.[6] But while the bakery enjoyed immense success, not everyone was happy with the way things were progressing.

The Capitol, supposed to be the grandest and most important building in the country, was falling apart. The renovation project had all but stopped, and doorkeeper Isaac Bassett had to remind troops not to spread grease and filth along the marble walls.[7] On May 20, the government called to remove all soldiers from the Capitol by the first of June to restore the building to its proper condition by Congress’s special session in July. As the troops filed out, busy hands got to work on cleaning, and Architect Walter and crew began again on the renovations. But while the soldiers could be housed elsewhere, the army’s Commissary General argued that the Capitol, with its plentiful gas lines, was the only feasible location for a bakery large enough to feed them. At this point, the bakery produced enough bread to nourish all troops within a ten mile radius and seemed crucial to the survival of the Union.[8] Authorities agreed that it would stay.

Over the course of the summer, the Capitol bakery produced an impressive amount of bread. By September, the 20 ovens were “turning out daily 60,000 loaves, requiring 230 barrels of flour, or over 1,600 barrels weekly, as the bakery [was] in full blast day and night, including Sundays.”[9] The operation employed around 150 men under the supervision of Lieutenant Cate, and even more were hired to drive wagons that would pick up the bread in the morning and deliver it to troops throughout the day. But especially with the limited technology of 1861, the bakery soon became a nuisance to those working in the Capitol.

Senators began to rise up against the bakery as the weather grew colder. Many of the smoke flues attached to the ovens ran into the hot air flues that warmed the Senate chamber. It was thus impossible to heat the room without smoke flooding in. This became even more of a dilemma when the same problem was discovered in the Congressional Library, occupying the floors just above the bakeries. Soot started to cover the books, causing Librarian of Congress John G. Stephenson to write to Benjamin B. French, the Commissioner of Public Buildings, on October 14:

“I am pained to see a treasure entrusted to my care – a treasure that money

cannot replace – receiving great damage from the smoke and soot that penetrate

everywhere through the part of the Capitol which is under my charge without any

means at my command to prevent it. I am now satisfied that there is no remedy,

except in the removal of the circle of bakeries that hems us in, and of those directly

under the library.”[10]

And so the Capitol bakery came under attack. In December 1861, the Senate passed a measure of inquiry to know by what authority the bakery had been constructed. The army’s Commissary General responded that authority had not been granted to build the bakery, but “maintained that it was wartime and he did not need permission.”[11] The sooty senators demanded he move it to the Old Gas House building just west of the Capitol. But representatives from the House argued it would be too costly to move the bakery that nourished so many troops. When they voted to keep it in the Capitol on December 17, Senator Solomon Foot sarcastically remarked: “I think it advisable to request the House, since their patriotism will not allow them to have the bakeries removed, to remove them over to their side.”[12] Soon after, he called on French to write to Lincoln.

But bureaucratic procedures are known to take a while, and they take even longer in wartime. It wasn’t until the next year, in the summer of 1862, that Lincoln intervened and appropriated $8,000 to remove the bakery and repair the damage it caused.[13] Within months, the bakery had been relocated elsewhere and the Capitol was back to serving its intended purpose. The building breathed a sigh of relief, and Walter was especially pleased that renovation could finally be completed. On December 2, 1863, no trace of the great bakery even existed as the statue of Freedom was placed on the Capitol’s completed dome.

Footnotes

- ^ Lincoln, Abraham, “Proclamation on State Militia,” 15 April 1861, Library of Congress, accessed 23 June 2015.

- ^ Gugliotta, Guy. Freedom’s Cap: The United States Capitol and the Coming of the Civil War… 379-380.

- ^ Leech, Margaret. Reveille in Washington, 1861-1865… 90.

- ^ “Troops Quartered in the Capitol at Washington,” The Independent, 25 April 1861.

- ^ “A Soldier’s Ration,” Evening Star, 13 May 1861.

- ^ “Seizure of Flour,” The National Republican, 22 April 1861.

- ^ Bassett, Isaac, “The Isaac Bassett Papers,” U.S. Senate, accessed 23 June 2015.

- ^ “Seventy Thousand Rations,” Evening Star, 27 June 1861.

- ^ “From Washington: Government Bakeries,” Cleveland Morning Leader, 25 September 1861.

- ^ “The Capitol as a Bakery,” The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, accessed 22 June 2015, www.philaathenaeum.org/EVExhibit/section4.html

- ^ Gugliotta, 385.

- ^ Congressional Globe, (37th Congress, 2nd session: ser. 1124), 17 December 1861.

- ^ “Congressional: XXXVIIth Congress – Second Session,” Evening Star, 11 June 1862.

>

>