"Belair at Bowie": Segregated Suburbia

By 1963, “Belair at Bowie” was thriving. Since its opening in 1961, over 2,000 of the Maryland development’s homes had been occupied.[1] Every week, real estate agents at the Belair offices sold 35-40 more, with even more streets and neighborhoods planned to meet the steady demand.[2] Churches and schools were being built around the new homes, businesses were moving into the shopping center, and a private bath and tennis club had just opened to residents. Thanks to the growth, Bowie had even become a city, with its own mayor and local government. From the beginning, Belair’s chief creator and salesman, the property developer William Levitt, had envisioned the ideal community: attractive, affordable, spacious, friendly, and convenient. Now, three years after he first came to the Washington area, that community was “a complete one.”[3]

But, evidently, Levitt’s vision of the perfect neighborhood only included one type of neighbor: white.

In July 1961, nine months after Belair first opened to sales, Levitt’s company was accused of racial bias. The Washington Post reported that “Levitt salesmen refused to sell houses to two Negroes,” having told the potential buyers that the new development was “for whites only.”[4] It shouldn’t have come as a surprise, since other Levittowns — other Levitt communities in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania — followed the same unofficial but prevalent rule.[5] Even in 1957, when Levitt was still trying to convince the local Prince George’s County council that “we will be good neighbors,” he assured them he was planning an ideal community, not “any insipient slum area.”[6] They must have understood exactly what he meant.

The controversy caught the attention of the American Veterans Committee (AVC), since the two men denied housing had applied for a home loan through them. The AVC was also concerned by another incident, in which “non-white diplomats” had been denied housing in the area.[7] International reputation, as well as injustice at home, was now at stake — Levitt couldn’t be another offender. “It is incredible that a racist policy should be established for a development of 4000 houses,” the AVC said in a statement. “It is obvious that our foreign relations might further be damaged should an African or Asian diplomat seek housing in Belair ... however, AVC is equally concerned about the treatment of Americans.”[8]

The AVC, partnering with local civil rights groups, took the fight directly to President John F. Kennedy. They urged him to pass an executive order that would advocate for fair, equal-opportunity housing throughout the country — and they cited “the large Maryland housing development being completed near Bowie, Md., by the William Levitt firm” as a specific offender.[9] Since Levitt’s racist policies also attracted attention at his other developments in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Kennedy was persuaded to take action.[10] On November 20, 1962, he signed Executive Order 11063, which permits agents to “take all action necessary ... to prevent discrimination because of race, color, creed, or national origin” in developments that received federal financial assistance.[11] It was a victory, right?

Not quite. In the months following the order, it became clear Levitt had no intention of changing his practices. At a shareholders meeting, he declared that his company would make decisions based on business strategy, rather than “sociological and moral questions.”[12] He continued: “We will integrate, or not integrate, solely on the basis of what is good economically.”[13] And Levitt was just the famous face of a wider issue — other area developers and landlords also actively denied housing to people of color. It meant Levitt faced little pressure from officials, only activist organizations, and individuals desperate for change.

The tension reached a boiling point in December 1962, when Levitt salespeople refused to sell homes to black clients — again. Karl D. Gregory, an economist at the Bureau of the Budget, was struggling to find affordable housing for his growing family and, despite the controversy, decided to try buying in Belair. Knowing Levitt’s history, he brought two white friends and advocates with him. The two white men, Marvin Caplan and Peter Robertson, entered the sales office first, where they were welcomed by a clerk and told all the available buying options. When Gregory sat down with them, the deal was suddenly off the table. The clerk informed them “the company policy was not to sell to Negroes” before refusing to accept Gregory’s $100 deposit.[14] Caplan — a Levitt shareholder — and Robertson — the President of the National Capital Clearinghouse for Housing Democracy — urged Gregory to file a complaint with the Federal Housing Administration (FHA).

Though the FHA agreed to advocate for Gregory and “attempt to break the race barrier at Belair,” they admitted that Levitt had the legal advantage.[15] Thanks to a loophole in Executive Order 11063, Belair at Bowie was actually exempt from the new housing law. “The terms of the executive order apply only to FHA commitments taken out after Nov. 20,” a Levitt spokesperson argued. “Our commitments were taken out before that date.”[16] Because Levitt had already received his funding, federal agents couldn’t enforce the executive order. Gregory’s case was picked up by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, the Civil Liberties Union, and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), but it was ultimately a losing battle. By early summer, it seemed that they were powerless against the legal loophole. In June, the FHA declared “that it can do nothing about practices of the developers, Levitt and Sons.”[17]

For his part, Levitt seemed unfazed. Though protests had forced him to relax his segregationist policies at other Levittowns, he dug in his heels when it came to Bowie — the company continued to adhere to the idea that the integration of Belair was bad for business. Not only would white buyers be put off, Levitt “didn’t think an open-occupancy policy would bring any big rush of Negro buyers.”[18] His reasoning, as quoted by the press, was as horrific then as now:

“In the first place ... the Negro is the same as any other minority group. He is clannish and tends to select neighbors who are of the same background and race as he ... The other major factor is the price bracket. Our houses sell for $17,000 to $27,000 and this obviously eliminates all those who can’t afford such housing.”[19]

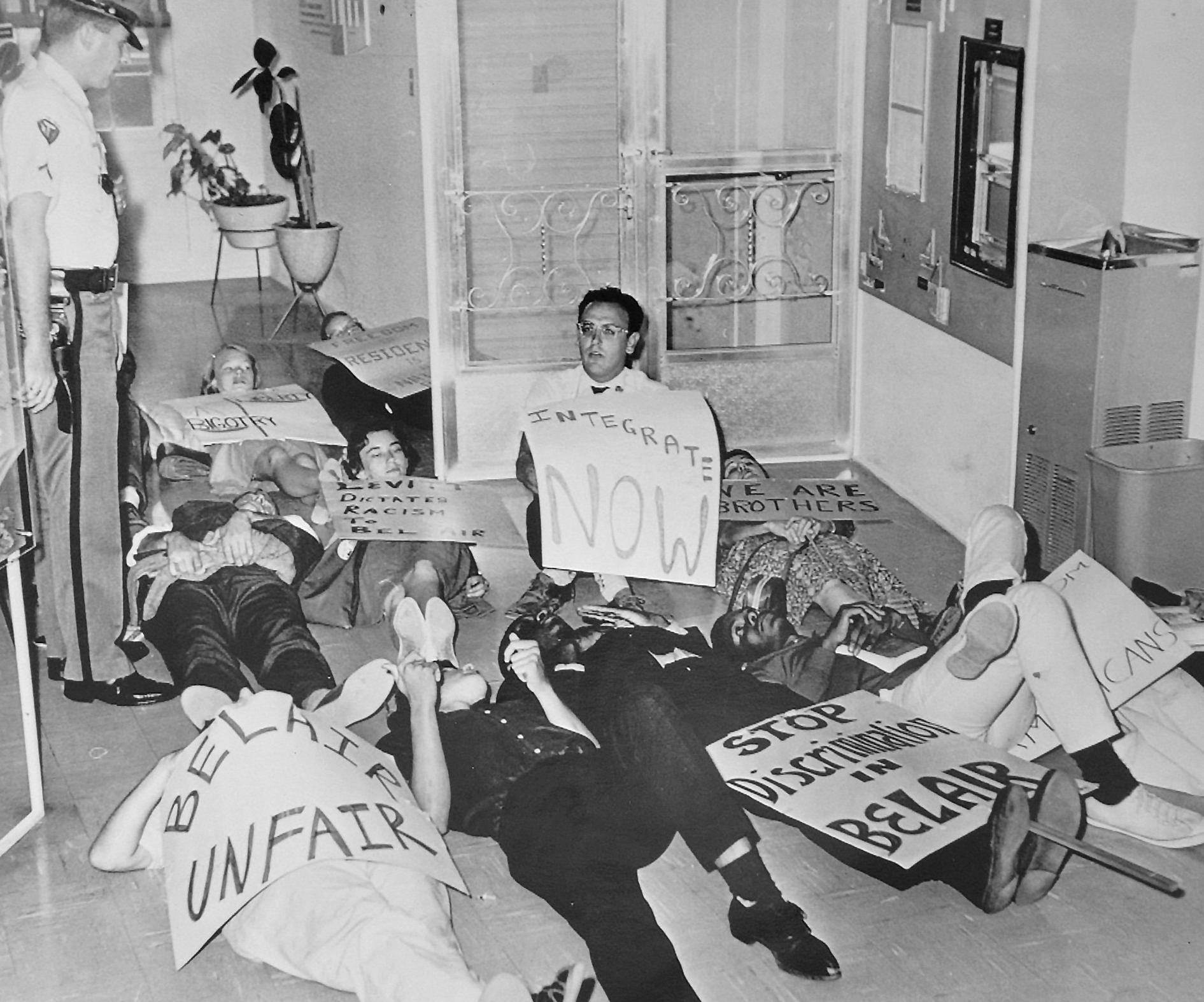

Outraged by Levitt’s refusal to integrate, CORE — the organization heavily responsible for organizing the Freedom Rides — decided to stage a summer-long picket of the Belair development in 1963. Activists marched along the street of model homes, where the main sales office was located. They also called on prospective buyers and Belair residents to join their protest, putting pressure on Levitt’s company.[20]

CORE picketed the Belair office all summer and into the fall, eventually expanding their protest to other area developments that followed Levitt’s example. The largest day saw 150 picketers marching, staging sit-ins, and deterring Levitt customers — many were arrested.[21] Still, Levitt refused to budge, even filing for a restraining order when the marches and sit-ins began preventing normal operations.[22] By October, the CORE demonstrations ceased. Levitt, victorious, went ahead with more expansion, adding numerous “sections” to the Belair community.

Officially, Belair at Bowie remained whites-only. The Levitt sales team continued to refuse houses to any black clients, who still tried and failed to buy throughout the 1960s. The policy even extended to Levitt’s other developments in the Washington area, including Greenbriar in Fairfax County. Nothing changed until April 1968, following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Perhaps seeing the writing on the wall, Levitt announced that the company was dropping its non-integration sales policy “as a tribute to the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.”[23] In many ways, it was a hollow gesture since Congress was about to pass a civil rights bill that included more specific bans on housing discrimination. But, regardless, the fight was over at last.

And in the end, Levitt really did lose. However much his legacy carries on in Bowie — in his houses, his sectioned neighborhoods with the alliterative streets, in his schools and churches — he probably didn’t foresee his community’s ultimate fate. The Levitt and Sons company couldn’t control the re-sale of houses to black families — nor defy the new civil rights laws — so, over the years, Belair residents gradually gained more black neighbors.[24] According to census data from 2000, Prince George’s County is now the wealthiest majority-black county in the United States — and Bowie the largest city within that county.[25] Most of the people currently living in Levitt’s houses, in communities he designed or inspired, are the people he didn’t think worthy enough in the 1960s.

Footnotes

- ^ John V. Reistrup, “Town Has 10,000 Newcomers but No Old-Timers: Putting Down Roots,” The Washington Post, May 4, 1963.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Builder Levitt Accused of Bias in Home Sales,” The Washington Post, July 15, 1961.

- ^ David Kushner, Levittown: Two Families, One Tycoon, and the Fight for Civil Rights in America’s Legendary Suburb (New York: Walker & Company, 2009), 64.

- ^ “Belair Won’t Lift Taxes, Levitt Tells ‘Neighbors,’” Washington Evening Star, December 18, 1957.

- ^ “Builder Levitt Accused of Bias in Home Sales,” The Washington Post, July 15, 1961.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Housing in Washington: Hearings Before the United States Commission on Civil Rights 81-962 (Washington, D.C.: 1962), 237.

- ^ Kushner, 193.

- ^ “Executive Orders: Executive Order 11063—equal opportunity in housing,” The National Archives: Federal Register, https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/…

- ^ “Levitt May Lift Racial Bar Here,” The Washington Post, June 30, 1962.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Rasa Gustaitis, “House Sale Refused, Negro to Tell FHA,” The Washington Post, December 16, 1962.

- ^ “Kim Willenson, “FHA to Take Up Charge of Belair Discrimination,” The Washington Post, February 4, 1963.

- ^ Gustaitis, “House Sale Refused.”

- ^ “Can’t Crack Belair Ban, FHA Says,” The Washington Post, June 16, 1963.

- ^ “Negro Ban Reaffirmed by Levitt,” The Washington Post, August 30, 1963.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Three ‘Sleep-In’ at Housing Tract After Rival Groups Picket Salesroom,” The Washington Post, August 11, 1963.

- ^ “150 Pickets Are Led by CORE in Belair,” The Washington Post, October 7, 1963.

- ^ Donald Himes, “Levitt Given Permission to Seek Picket Injunction,” The Washington Post, October 25, 1963.

- ^ Bart Barnes, “Levitt Drops Sales Ban to Subdivision Negroes,” The Washington Post, April 10, 1968.

- ^ Kushner, 193.

- ^ Tom Howell, Jr, “Census: Md. Economy Supports Black-Owned Businesses,” Census 2000: Maryland Newsline Special Report, April 18, 2006.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)