The Michelangelo of the Capitol

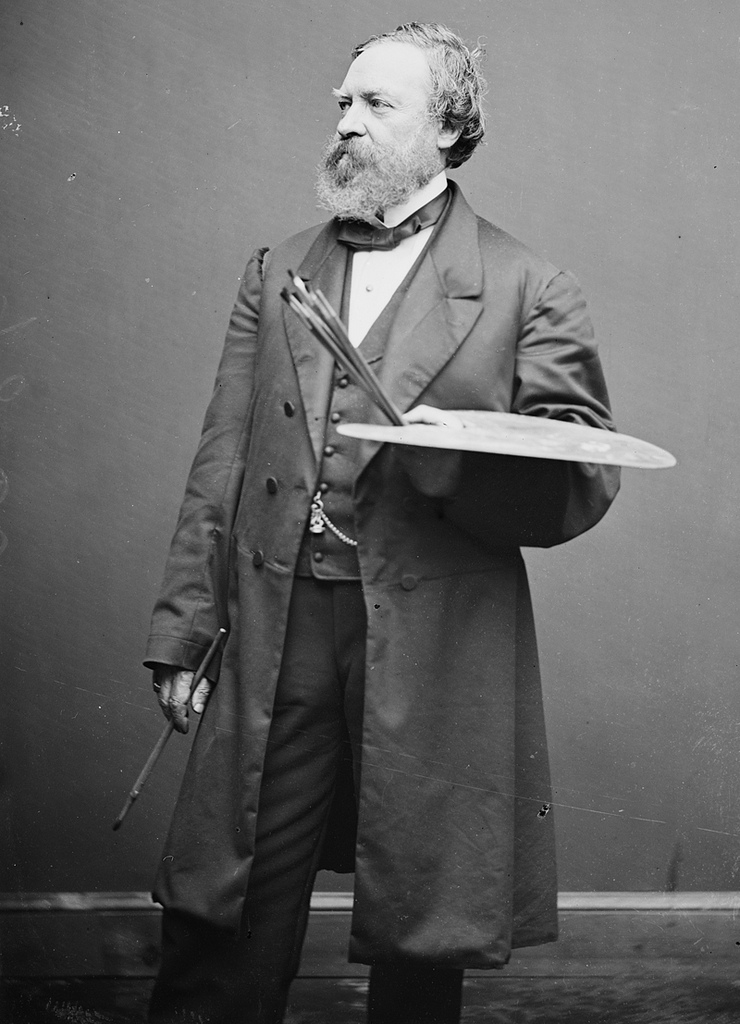

In the U.S. Senate's sculpture collection, there are plenty of busts of instantly recognizable historical figures such as Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln. But enshrined alongside them, there's also the lushly-bearded, bowtie-wearing likeness of an obscure 19th Century Italian-American artist. While Brumidi, who signed his work "C. Brumidi Artist Citizen of the U.S.," isn't a famous name, he left a lasting mark on the U.S. Capitol, by creating striking frescoes and murals that add charm and grace to the building's interior.

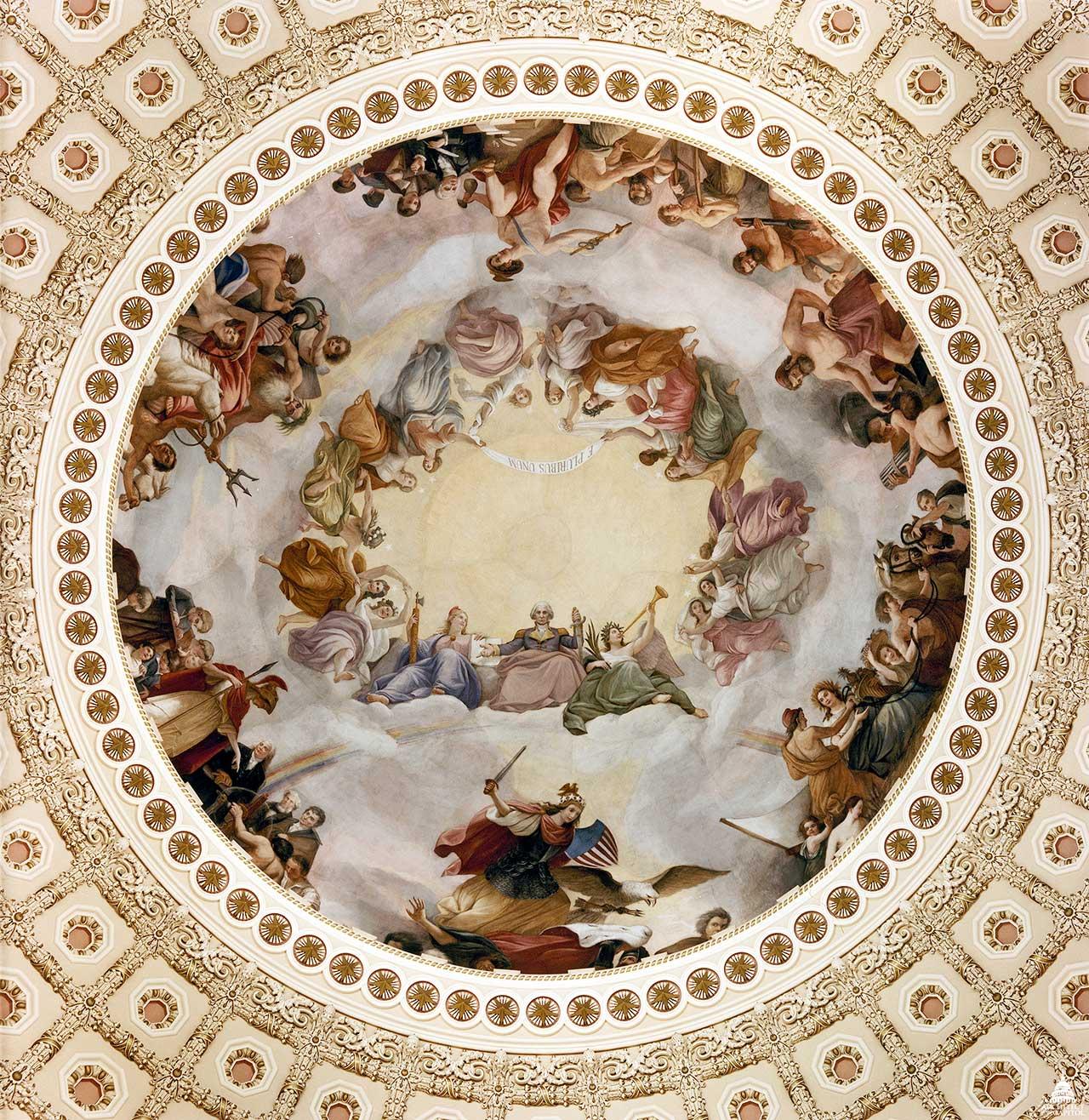

Brumidi's work, which can be found throughout the Capitol, includes the fresco The Apotheosis of Washington in the Rotunda canopy. But his masterwork is the hallways on the first floor of the Senate wing, an assortment of frescoes and murals known as the Brumidi Corridors. Inspired by Raphael's Loggia in the Vatican, Brumidi's art is distinguished by his blending of classical imagery with patriotic American themes. The Washington Post once described Brumidi as "the genius of the Capitol," and noted that "so many of its stateliest rooms bear the touch of this tireless brush that he shall always be associated with it." Art historian Francis V. O'Connor has called him "the first really accomplished American muralist." A journalist of his time went even further, labeling him "the Michelangelo of the U.S. Capitol."

It's odd to think that the man who earned such accolades came to the U.S. under a cloud, fleeing to avoid a prison sentence for revolutionary activities, and that his foreign birth and skill as as a muralist earned him some enmity from American artists who, as O'Connor puts it, "could not paint a wall to save their lives."

Brumidi was born in Rome in 1805, before Italy became a unified modern nation. His father owned a coffee shop. He began studying art at age 13 at the Academy of St. Luke. There, he spent the next 14 years learning how to paint in various media — including the difficult art of fresco painting, in which pigments are applied to freshly-laid, wet plaster, which allows little margin for error, and forces an artist to work against the clock to finish a section before the plaster dries. Painting on walls had a venerable history in Italy, and Brumidi eventually found work decorating the villa of a wealthy family with some of the same classical motifs that he later used in the Capitol. As his talent won recognition, he also was hired by the Vatican, for whom he restored frescoes and painted church murals. He was so highly thought of that he was even commissioned to paint the official portrait of Pope Pius X.

Even so, Brumidi was not paid enough to make a living solely as an artist, and he helped support his family by continuing his father's coffee shop. He continued along that path uneventfully until 1849, when Italy — like other parts of Europe — fell into revolutionary turmoil. After revolutionaries seized Rome and the Vatican, Pius IX was forced to flee the city in a disguise. Brumidi, who reluctantly served as a captain in the Papal civic guard, by one account removed valuable objects from church buildings to hide them from looters; when order was restored, what sounds like diligence on Brumidi's part was interpreted as thievery, and he was arrested, jailed for 13 months, and eventually sentenced by a court to 18 years in prison. The U.S. Capitol might have bare walls today, except that the pope whose portrait he'd painted took pity upon Brumidi and pardoned him, with the understanding that he would leave Italy and go to the U.S., where he had been offered work decorating churches. (Brumidi would later romanticize his revolutionary experience, claiming that he'd been arrested because he refused to fire on civilians.)

When Brumidi arrived in New York in 1852, he was nearly 50 years old. He cut an odd figure — just five feet five inches tall, with wild, unruly hair and a bushy beard, and gray-blue eyes that contrasted with his dark complexion. With his bohemian appearance, it would have been easy to mistake him for an anarchist revolutionary. But Brumidi was grateful to still have his freedom, and he had no interest in stirring up any more trouble. Instead, he immediately applied for U.S. citizenship and then began working energetically, taking on commissions to do private portraits and painting alterpieces and murals in churches, including a 22-by-44-foot mural of the Crucifixion in St. Stephen's in Manhattan that the New York Times once noted "rivals Baroque masterpieces in Italy."

But in December 1854, the opportunity of a lifetime came Brumidi's way. He traveled to Washington and managed to land an interview with with Capt. Montgomery C. Meigs, the engineer who supervised the expansion of the U.S. Capitol that had been designed by architect Thomas U. Walter. Meigs had a vision for decorating the Capitol's expanded interior with artwork inspired by the Vatican and the villas of Pompeii, and Brumidi — an Italian with a demonstrated mastery of fresco technique — seemed like a perfect fit for the job. Brumidi painted a test mural depicting the Roman general and dictator Cincinnatus, and it was so successful that he got the job of decorating the rest of the Capitol. He began in 1855, and continued for the next 25 years, until his death.

It was a monumental task, especially for a man who didn't even speak or write in English when he started it. (A quick study, he somehow taught himself the language as he worked, and within a few months was writing letters in English, albeit ones filled with grammatical errors.) Meigs and other American officials suggested general subjects for his work, but it was up to Brumidi to fill in the details. He went to the Library of Congress and studied books on American history, and familiarized himself with James Herring's 1854 book National Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Americans, to get an idea of how to depict famous figures. All that merged in his mind with the classical Roman artwork and architecture that he'd studied in his youth. "He tried to make his work American," the Washington Post noted in his obituary.

Brumidi's Apotheosis of Washington, which he completed in 1865, exemplifies his blend of classical and patriotic themes. The immense fresco, which looms 180 feet above the floor in the eye of the Capitol Rotunda, depicts a godlike Washington rising toward the heavens, surrounded by women representing liberty and victory.

In 1878, at age 73, Brumidi began his final work, the ambitious Frieze of American History, which encircles the Rotunda. Two decades before, Brumidi had sketched out the plan for a series of scenes, beginning with the landing of Columbus, rendered in a fashion that would create the illusion of monumental sculpture. But by then, the artist was in failing health, and the task turned out to be too arduous. While working on the scene of William Penn with the Indians, his chair slipped on the scaffold, and he was left clinging to the rung of a ladder 50 feet up for 15 minutes, until he could be rescued. The mishap took something out of him, and he was able to return the scaffold only one more time. He spent his last few months at his home at 921 G Street NW — now the site of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Library — working on drawings, before passing away in February 1880. The Frieze eventually was taken over by two other artists, Filippo Costaggini and Allyn Cox, who completed the last three panels in 1951.

In 2014, the Government Printing Office published a new edition of a book devoted to Brumidi's work, Amy Elizabeth Burton's To Make Beautiful the Capitol: Rediscovering the Art of Constantino Brumidi.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)