"The Obstinate Mr. Burns" and the First White House

In July 1885, the Daily Evening Bulletin, a Washington newspaper, gave its readers a local history lesson: “Reminisces of the Oldest House in the District.” The house in question—an old, dilapidated little cottage on 17th Street—was once “the cottage in which David Burns lived…one of the first residents of Washington."[1] Burns (or Burnes, as he spelled it) was, indeed, one of the original landowners in the area. The whitewashed cabin, his own residence, was all that remained of his large family farm. Looking at it, you might not guess that Burns was actually a very wealthy man, and very protective of the land that provided his wealth. That land—particularly, its prime location—made him infamous.

Within local legend, David Burns is better known as “the obstinate Mr. Burns,” a moniker given to him by the man he really managed to irritate: George Washington.

In 1791, Washington was busy planning his namesake city. Congress had just approved and passed the Residence Act, which allowed the President to create a new national capital on the banks of the Potomac River. It seemed relatively easy: Washington chose the spot he wanted, then Maryland and Virginia ceded the land. There was a small complication, though: the area was already home to several settlements and farms, all privately owned. If the President and his agents wanted to build government offices, grand avenues, and a Presidential mansion, they would have to make deals with the landowners.

It was messy and confusing, to say the least. Landowners gossiped and grouped together, trying to predict whose lands would be needed for the project. Washington and his agents changed the capital’s prospective borders a few times.[2] Eventually, though, the surveyor Andrew Ellicott laid out the official boundary lines of the ten-mile square city. Plans were made by the architect Pierre L’Enfant, indicating ideal locations for the government and public buildings, parks, and streets. When Washington’s agents finally approached the necessary landowners, many of them were ready to comply. Some negotiations did take place, land prices went as high as £25 per acre, but most were persuaded to sell.[3] Because, really, who would dare refuse George Washington—the President and hero of the country? Who wouldn’t be honored to see their land used for impressive buildings of national importance?

David Burns was known for being a difficult neighbor. If he believed that anyone had encroached on his land, he took them to court; if he believed that tenants defied property agreements, he forced them off the land.[4] One history of the city, written in 1884, calls him “a very bigoted, choleric Scotchman…fond of controversy, and never known to agree with any one in the slightest particular.”[5] But he was also one of the richest men in the area, since he owned a 600-acre tract right in the heart of Washington’s planned city. The land included Burns’s tobacco farm, orchards, a swampy area adjoining a creek, and the rickety house where his family lived. According to the 1790 census, Burns also owned twelve slaves, who lived in cottages elsewhere on the property.[6] Nowadays, his land is better known as the area around the White House. Lafayette Square, for instance, was built on the peach orchard.

When Washington’s agents approached Burns, hoping to secure his vast tract of land for their own use, he refused to accept their offers. Knowing his property was in high demand, Burns seemed to be holding out for a higher price—or, at least, terms more favorable to him. Based on what’s known of his personality, this doesn’t seem out of character. After several failed attempts to purchase Burns’s land, the matter came to the attention of Washington. “If you have concluded nothing yet with Mr. Burns,” he wrote his agents, “nor made him any offer for his land that is obligatory, I pray you to suspend your negotiations with him, until you hear further from me.”[7]

According to legend, a frustrated Washington decided to travel to Burns’s little white cottage himself, to “use all his powers of persuasion to bring about sale.”[8] Their interaction is only recounted in later local histories, most of which tell slightly varying—but very colorful—versions of the story.[9] “The curtains part to reveal the farm and orchard of the Scotch farmer, David Burns,” describes one play, written in 1932 to celebrate Washington’s 200th birthday. “Washington appears…and [knocks] on the door.”[10] The President was there to engage in calm, gentlemanly conversation, but the famous general and statesman was no match for the “sturdily built, florid” Mr. Burns—apparently, “his manner is not gracious.”[11]

The two men sat down under a tree by the creek, Washington ready to plead his case. But his attempts at civility were quickly shut down by Burns. After refusing to sell his land, he leveled a harsh blow on the President. “I suppose you think that people here are going to take every grist that comes from you as pure grain,” Burns shouted, “but what would you have been if you had not married the rich Widow Custis?”[12] Since Washington had been a relatively modest landowner before his marriage to his wife Martha, who inherited property and slaves from her first husband, this attack must have angered him—the quote is repeated by every author on the subject. Growing angry, he threatened Burns with his technical right to seize any land he needed to build the capital city, reiterating that “I have selected your farm as part of it, and the Government will take it…I trust you will, under the circumstances, enter into an amicable agreement.”[13]

In all versions of this story, Washington is the slighted hero. The hostile but somewhat amusing conversation makes for perfect local lore, especially within these nineteenth-century history books. But contemporary sources actually show another side to the story, one a bit more sympathetic to Burns. In February 1793, he wrote to Washington to explain his position—and despite his portrayals as a simple, uncivilized old man, the letter is eloquent and humble. “Sir,” he writes, “I presume to address you a second time on a subject which naturally concerns me and my family.”[14] Unlike other landowners in the area, who owned various properties and weren’t forced to sell the land they actually lived on, Burns owned “no other Lands than those in the Center of the City.”[15] The farm had been in his family since the 1690s, passed down through generations. Ideally, he wished to keep some of his home intact, but the planned city blocks would leave the land “all cut up and rendered useless for farming.”[16] In another letter, Burns even explained to Washington “with great deference” that he kept refusing agents because local gossip accused “speculators” of making inaccurate offers on the President’s behalf.[17] Reading accounts of the District’s earliest years, it seems to have been a very confusing time for landowners, who suddenly felt compelled to give up their farms and cooperate with Washington’s agents. If Burns was playing hard to get, it was probably because he just wanted to keep his land.

But, of course, the new capital city couldn’t have a large tobacco farm at its center. Washington and his agents didn’t give up their fight against Burns, continuously making new offers and threatening to seize pockets of his land through force. When L’Enfant began to survey the lands already purchased by Washington, the President instructed him to begin at the very edge of Burns’s property, “to scare” him—ironically, L’Enfant ended up befriending Burns and offered to design a mansion for him on the site of the cottage.[18] Gradually, though, Burns complied and sold off parts of his land for increasingly higher prices. Washington, feeling triumphant, bragged to Thomas Jefferson that “even the obstinate Mr. Burns has come into the measure.”[19]

But Burns did manage to have the last laugh, in his own way. Even if the stories of his rude defiance are merely legendary, the evidence shows that he held off Washington for as long as possible. He sold his land acre-by-acre, increasingly convinced that the city planners didn’t actually intend to use all of it. Throughout the 1790s, even as he developed a fatal illness, he continued to be “the obstinate Mr. Burns.” In 1798, when city building was well underway and Washington was no longer President, he finally sold the remaining lots of his land to private investors.[20] The government never got all of it. Burns died inside his cottage in 1799—the same year as Washington.

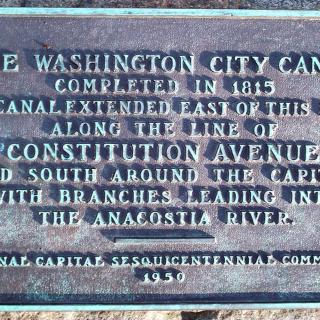

After Burns died, his daughter Marcia became one of the wealthiest heiresses in town. She ended up marrying General John P. Van Ness, a Congressman from New York—later, he became mayor of the new city and the namesake of the D.C. neighborhood. The couple lived in a mansion on what remained of the Burns property: a city block surrounded by C Street, Constitution Avenue, 17th Street, and 18th Street. According to legend, Marcia refused to demolish the little white house in which she had grown up.[21] It stood on the property, a testament to her father’s obstinance, until the late 1890s.

Footnotes

- ^ “Washington Gossip,” The Daily Evening Bulletin, July 28, 1885.

- ^ Bob Arnebeck, Through a Fiery Trail: Building Washington 1790-1800 (New York: Madison Books, 1991), 33.

- ^ Arnebeck, 36.

- ^ Arnebeck, 37.

- ^ Joseph West Moore, Picturesque Washington (Providence: J.A. & R.A. Reid, 1884), 32.

- ^ “First Census of the United States,” The National Archives, https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/_/GQFfAdPkgG-_XQ

- ^ “From George Washington to William Deakins, Jr., and Benjamin Stoddert, 28 February 1791,” The National Archives: Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-07-02-0262

- ^ Harvey W. Crew, William B. Webb, and John Wooldridge, Centennial History of the City of Washington D.C. (Dayton: United Brethern, 1892).

- ^ The story, in varying forms, can be found in the sources listed in Footnotes 8-13.

- ^ Marietta Minnigerode Andrews, “Many Waters: A George Washington Pageant,” in History of the George Washington Bicentennial Celebration 2 (Washington, D.C.: 1932), 719.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Mary Clemmer Ames, Ten Years in Washington: Life and Scenes in the National Capital (Hartford: A.D. Worthington & Co, 1873), 36.

- ^ Crew, Webb, and Wooldridge.

- ^ “Letter from David Burns to President George Washington,” The National Archives: Records of the Department of State, https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/_/igFNfbLDEboh8g

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Arnebeck, 40.

- ^ Arnebeck, 39.

- ^ “From George Washington to Thomas Jefferson, 31 March 1791,” The National Archives: Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Author%3A%22Washington%2C%20George%22%…

- ^ “Letter from David Burns to President George Washington,” The National Archives: Records of the Department of State, https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/_/igFNfbLDEboh8g

- ^ “Washington Gossip,” The Daily Evening Bulletin, July 28, 1885.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)