Black History Sites in D.C. That Deserve More Attention

Recently, Washington’s Black community has – rightfully – pushed for more memorials and markers honoring Black leaders and the city's rich African American heritage. While we wait for our city’s landscape to reflect more of its history, we highlight some existing sites that deserve more attention.

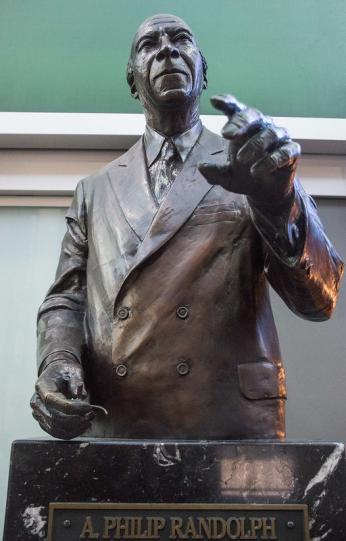

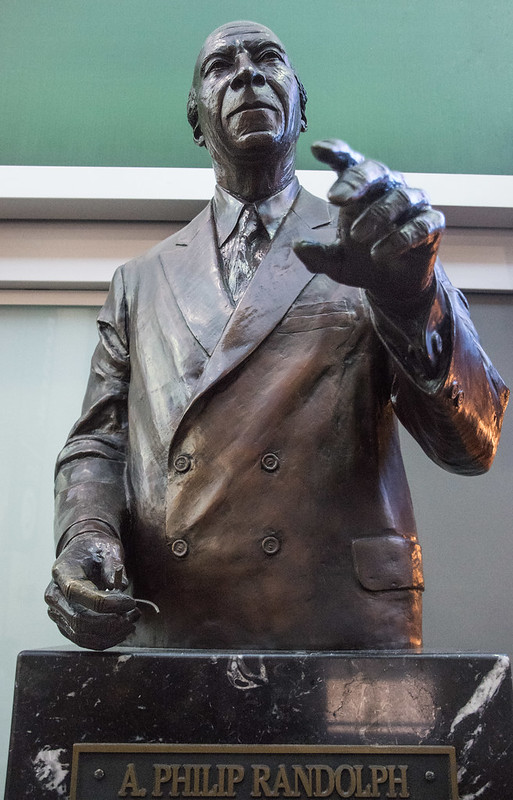

1. A. Philip Randolph monument, Union Station (interior).

This impressive bronze sculpture honoring Civil Rights activist A. Philip Randolph may seem unusually located, but its placement also means you’ve likely passed by Randolph’s likeness often while heading in and out of D.C. The monument sits in Union Station, not far from the station’s Starbucks café. History professor Touré Reed explains that its placement is a thoughtful nod to Randolph’s “career as a successful civil rights organizer.”[1] Randolph took on one of his first roles as a Civil Rights activist in 1925, when the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, “one of the first labor unions led by Black Americans,”[1] elected Randolph president. Artist Ed Dwight – a legend in his own right, as the first African-American to enter NASA’s Air Force training program – sculpted the monument.[2]

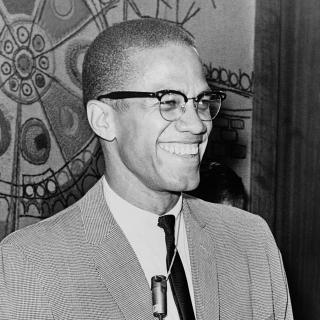

2. Malcom X. Park (also known as Meridian Hill Park), 16th St. & W St. NW.

Meridian Hill dates back to 1804 and has a rich history. Most Columbia Heights & Adams Morgan locals, though, remember the park most for its ties to Black history and the Black power movement.[3] In 1876, Meridian Hill was the site of Wayland Seminary College, one of the first higher education centers for newly freed people.[4] Later, in the 1960s, the park’s convenient proximity to the Pitts Motor Hotel made it a common gathering place for Black activists visiting the District.[5] Many credit scholar and activist Angela Davis for being the first to contest that Meridian should be renamed Malcom X. Park in 1969. Though congressional attempts to rename the park failed, you can still visit and pay homage to the “ground zero for Black power organizing in D.C."[5]

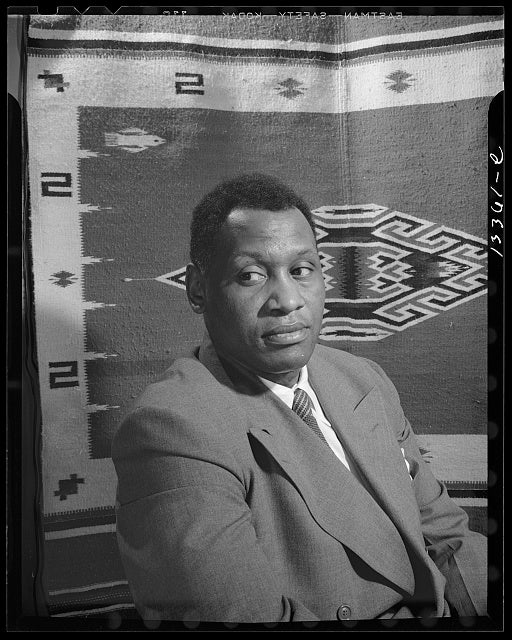

3. "Here I Stand – In the Spirit of Paul Robeson," intersection of Kansas Ave NW, Georgia Ave NW and Varnum St NW.

Paul Robeson, an athlete, singer, actor, and activist, never actually lived in D.C., but he certainly made waves in Washington. After earning an LL.B. from Columbia in 1923, Robeson took his baritone to Broadway and soon gained stardom. In the 1940s, though, his outspoken views regarding segregation and exploited Black workers, as well as his associations with communism, motivated the State Department to pressure the NAACP and Jackie Robinson to issue statements against Robeson.[6] It wasn’t long before Robeson became blacklisted. Robinson later amended his statement, commenting that Robeson “sacrificed himself, his career and the wealth and comfort he once enjoyed” in order to “sincerely…help his people.”[6] In 2001, Washington-based artist Allen Uzikee Nelson sought to honor Robeson’s legacy. Nelson sculpted “Here I Stand” (named after Robeson’s book) out of Cor-Ten steel and crafted the sculpture with African influences.[7]

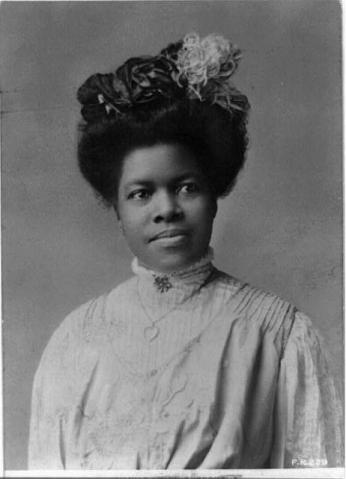

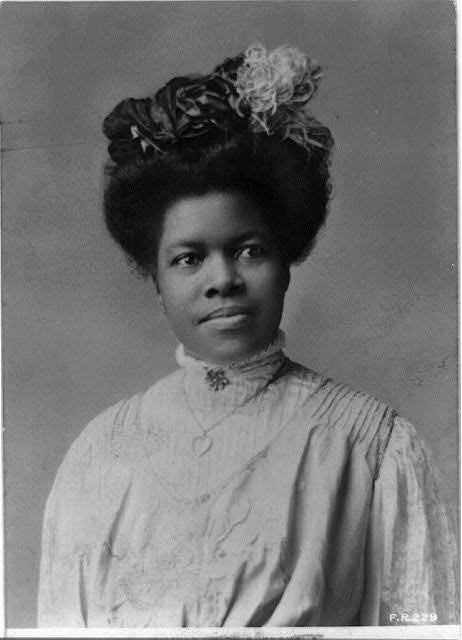

4. The Nannie Helen Burroughs School (formerly the Trades Hall of National Training School for Women & Girls), 601 50th St. NE.

Nannie Helen Burroughs was born in 1879 in Orange, VA to two formerly enslaved parents, but she moved to the District as a child.[8] A religious leader, activist, and educator, Burroughs is best remembered for her work with the National Baptist Convention, her support of Dr. Martin Luther King,[9] and, of course, her work in founding the first vocational school for African-American girls in 1909.[10] Burroughs believed the school could instill “the fiber of a sturdy moral, industrious and intellectual woman” into each student, and she curated a diverse, rigorous curriculum.[11] She served as the school’s principal until her death in 1961.[12] Though there’s not yet a statue to honor Burroughs herself, the Nannie Helen Burroughs school was recognized with a “gleaming bronze plaque” in 1976.[13] In 1991, the National Parks Service recognized the school as a historic landmark.[10] The school closed in 2006, but the Progressive National Baptist Convention, the building’s new occupants, continue to honor her legacy.[11]

5. The Whitelaw Hotel,1839 13th St. NW Washington D.C. 20009.

This grand hotel, founded by D.C. resident John Whitelaw Lewis, was one of the few places Black people could enjoy luxurious accommodation in Washington amidst racial segregation. Lewis started his career as a construction laborer, but he soon dedicated himself to ensuring that fellow Black District residents would be able to gain space in the city. In 1913, he founded the first Black owned bank in Washington, The Industrial Savings Bank, to help the Black community buy homes.[14] Not long after, Lewis began plans for a hotel built “by Black people and for Black people,” and he hired prominent Black architect Isaiah T. Hatten to oversee the hotel’s design. The Whitelaw Hotel opened its doors in 1919, and by the 1930s, it was well-known as the regular gathering place for “Washington’s black elite.”[15] Cornelius Jenkins, who worked at the hotel during its heyday, remembered that “if you [were Black and] were travelling through Washington, the Whitelaw was the only place you could stop. The big hotels were for white only.”[16] Jenkins carried the bags of “prominent figures like boxing champion Joe Lewis, entertainer Cab Calloway, civil rights lawyers Charles H. Houston and Thurgood Marshall,…and black scientist George Washington Carver.”[16] The Whitelaw’s popularity declined after WWII, as more hotels became accessible to Black patrons. In 1977, the hotel’s owner, Talley R. Holmes Jr., expressed concern over the gentrification of the area, worrying that the hotel would be razed for the construction of “luxury apartments.”[16] The hotel was slated for demolition later that year. Thankfully, a non-profit housing company acquired the hotel and restored it, opening the hotel up as affordable housing in 1992. The hotel was registered on the National Register of Historic Places soon after, and you can still admire its grand façade today.[17]

Footnotes

- a, b Natalie Zareli, “One of D.C.’s Best Statues is Hidden in Plain Sight,” History, 21 August 2017, https://www.history.com/news/one-of-dc-s-best-statues-is-hidden-in-plai….

- ^ Jacqueline Trescott, “African Americans honored by artworks throughout D.C.,” The Washington Post, 24 Aug 2011: H.17.

- ^ Rachel Kurzius, “Is it Meridian Hill Park or Malcolm X Park? Your answer is meaningful” The Washington Post, Nov 2, 2018.

- ^ “The School on Meridian Hill,” The Washington Post, 25 Mar 1999: A36.

- a, b Rachel Kurzius, “Is it Meridian Hill Park or Malcolm X Park? Your answer is meaningful” The Washington Post, Nov 2, 2018.

- a, b Gilbert King, “What Paul Robeson Said,” Smithsonian Magazine, 13 September 2011, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-paul-robeson-said-77742433/

- ^ Valerie Paschall, “Reintroducing Here I Stand,” Curbed Washington D.C., 11 February 2014, https://dc.curbed.com/2014/2/11/10145192/reintroducing-here-i-stand-in-…

- ^ “Nannie Helen Burroughs,” National Parks Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/nannie-helen-burroughs.htm

- ^ “Burroughs, Nannie Helen,” Stanford King Encyclopedia, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/burroughs-nannie-helen

- a, b “USDI Registration Form: National Training School,” National Parks Service, https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NHLS/91002049_text

- a, b “Trades Hall of National Training School,” National Parks Service, https://www.nps.gov/places/national-training-school-for-women-and-girls…

- ^ “Nannie Helen Burroughs,” Black Past, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/burroughs-nannie-hel…

- ^ Vernon C. Thompson, “Honoring a 'total person': Nannie Helen Burroughs,” The Washington Post (1974-Current file), Jul 8, 1976.

- ^ Millroy Courtland, “A former hotel still houses hope in D.C.” The Washington Post; Washington, D.C. [Washington, D.C]19 Feb 2020: B.1

- ^ Joseph D. Whitaker. “Washington: Whitelaw Hotel Is Closing After Checkered History Once Proud Hotel Ends in Misery,” The Washington Post (1974-Current file); Jul 4, 1977;

- a, b, c Joseph D. Whitaker. “Washington: Whitelaw Hotel Is Closing After Checkered History Once Proud Hotel Ends in Misery,” The Washington Post (1974-Current file); Jul 4, 1977;

- ^ “NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM,” United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/98001557_text

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)