Yarrow Mamout's Place in History

While at the D.C. Historical Studies Conference last month, I had the opportunity to meet local writer and lawyer James Johnston, who wrote, From Slaveship to Harvard: Yarrow Mamout and the History of an African American Family. Johnston's work details the little-known but fascinating life of Yarrow Mamout, a man who came to Maryland on a slave ship, won his freedom and became perhaps the most prominent African American in Washington in the early 1800s.

We asked Mr. Johnston to share Yarrow Mamout's story.

The house on Yarrow Mamout’s old lot in Georgetown was scheduled for demolition in 2012, but efforts were made to save any artifacts from his occupancy as well as his mortal remains from the bulldozer.

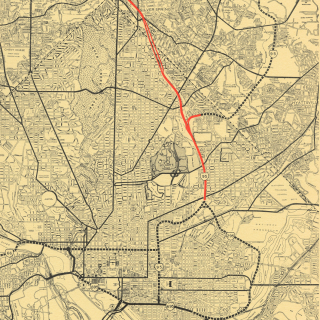

Yarrow Mamout was the most prominent African American in early Washington. He was a Muslim, educated in West Africa to read and write in Arabic. He and a sister arrived in America from on a slave ship in 1752. After forty-five years as a slave of the Beall family of Maryland, Yarrow (his last name) gained his freedom and settled in Georgetown. In 1800, he acquired the property at what is now 3324 Dent Place and lived there the rest of his life.

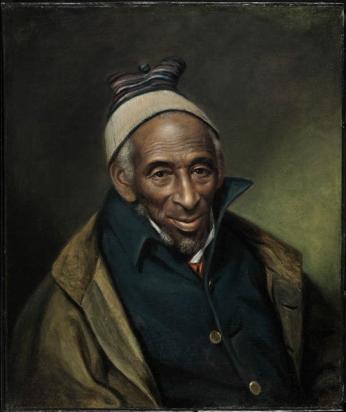

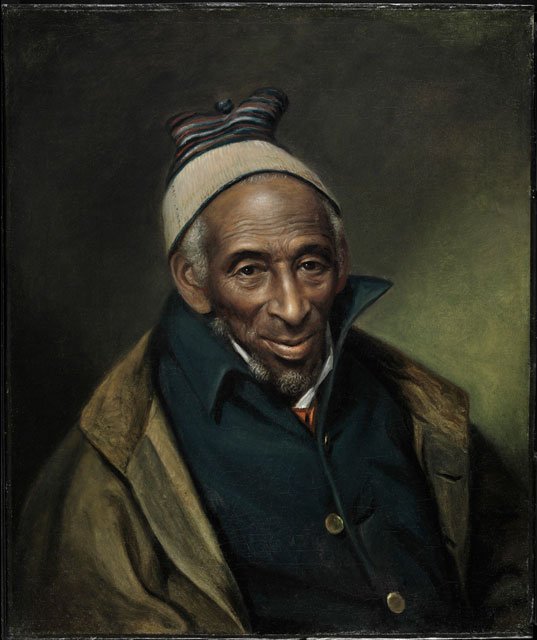

Portrait painter Charles Willson Peale heard of Yarrow while visiting Washington in 1818. He went to the Dent Place property and rendered a stunning portrait of the man. It is one of only two formal portraits of the 9.4 million people who came to the Americas on slave ships. The Philadelphia Museum of Art owns the painting. As Peale painted, he and Yarrow talked, and Peale wrote about their conversations in his diary. Thus, not only did the artist leave the portrait, he also left notes about Yarrow’s life. Peale said that besides the house and lot, the ex-slave owned stock in the Columbia Bank in Georgetown. In 1822, local artist James Alexander Simpson did another portrait of Yarrow. It hangs in the Peabody Room of the public library in Georgetown.

When Yarrow died in 1823, Peale wrote an obituary that was published in newspapers in Pennsylvania and Baltimore. It said Yarrow was buried in the corner of his lot, "the spot where he usually resorted to pray."

The property stayed in the family for several years after his death. In addition to the sister and her daughter, Yarrow was survived by a son and possibly a wife. But when the taxes on the property stopped being paid, it was sold at public auction in 1837. Wealthy Francis Dodge of Georgetown acquired the property then and probably rented it out. Dodge’s more infamous role in black history came in 1848 when he loaned his steamship Salem to the posse that chased and captured seventy slaves from Washington who tried to escape to the North aboard the sailing ship Pearl.

Yarrow’s house must have burned down or was torn down because the structure on the lot today is in the Italianate style, which came into vogue in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The lot was hardly the best address in Georgetown at the time Yarrow lived there: it bordered on the cemetery of the old Presbyterian Church. Things began to improve by the middle of the twentieth century. Newly-weds Jack and Jacqueline Kennedy rented a house across the street for a short period in the 1950s, and the neighborhood has since gentrified.

But, in the fall of 2011, a tree fell on the house, crushing the second story. Beyond repair, the property again went through a tax sale in the spring of 2012. The new owner applied for a raze permit to tear the house down. The Commission of Fine Arts has signed off and sent the application to the city government.

But demolition may pose a threat to any history that is still on the land. As mentioned, Yarrow was buried there. No one knows precisely where or whether the grave and his remains survive. Also of interest is the brick cellar beneath the house. Yarrow, among his many talents, was an excellent brick maker. An expert has said the bricks date from his time and so could be ones he made. Other artifacts from Yarrow’s occupancy might lie in the dirt under the cellar and in the large back yard. The new owner and the city have reportedly agreed to an archaeological investigation before the demolition.

James H. Johnston is the author of From Slave Ship to Harvard, Yarrow Mamout and the History of an African American Family (Fordham University Press, 2012). The book is available at Amazon.com and other booksellers.

The views posted on Boundary Stones are the views of the authors themselves and do not necessarily represent the views of WETA.

UPDATE 10/16/2020

Since Mr. Johnston wrote this piece, several updates have occurred, as pertains to the Yarrow Mamout property. In 2015, The Washington Post reported on an archaeological dig that happened onsite after the Italianite-style house was demolished. When archaelogists investigated the grounds, they discovered a cuff link, a glass medicine bottle, animal bones, clay marbles and pottery shards. What they didn't find was Yarrow Mamout's bones. Still, that doesn't necessarily mean that they weren't there. In the 1980s, the ground was disturbed when the owners installed a swimming pool, and in the words of forensic anthropologist David Hunt: "Bone does not survive real well in soils around here." According to an article on Curbed, Washington D.C., a luxury townhouse was completed at 3324 Dent Place NW in 2017 to be sold at $3.1 million the next year.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)