The Longest Walk's Final Destination

Content Warning: mention of the history of violence and genocide against Native Americans.

“Only the living Indian people here are the original people of America. Our roots are buried deep in the soils of America,” said Phillip Deere on the Capitol steps on July 17, 1978. “We are the people that still speak the language that was given to us by the Creator. Our religion has survived. Our languages have survived. Long before this building was built, our ancestors walked and talked the language I talk today. And I hope to see my Indian people continue to live long after this building crumbles.”[1]

Deere—a Muscogee (Creek) healer, spiritual leader and activist—was speaking to a crowd of thousands standing shoulder-to-shoulder, among a group of Native American protestors who had just travelled 3,000 miles for an event dubbed the Longest Walk. His voice was soft yet firm, and amplified by microphones over the sounds of chanting and the rhythmic clicks of camera shutters. The feather in his hair came to a vertical point that rivals the Capitol behind it.

The participants, hailing from more than 80 Indigenous tribes, began their journey at Alcatraz Island in San Francisco, and ended it in Washington, D.C. Thousands joined for parts of the journey, while a core two dozen demonstrators made the entire trek from sea to shining sea. Through changing terrains and changing seasons, the cross-continental journey was completed in July, five months after it began in February.

The Longest Walk was both a spiritual and political demonstration. On the spiritual side, it was meant to unify and strengthen the American Indian diaspora by practicing shared cultural and religious traditions. Politically, the protest sought to shed light on eleven bills that would strip Native nations of hunting, fishing, land and water rights, allow resources to be extracted from reservation land, and abrogate all treaties between the American government and American Indians.[2] Demonstrators also staged educational “teach-ins” across the country to raise awareness about other issues faced by Indigenous peoples, such as forced sterilization, environmental endangerment, and a lack of civil rights and equal opportunity.[3] (Check out this televised debate between Buffy Sainte-Marie and Rep. Jack Cunningham to see the two sides argue their positions.)

Beyond ideological battles and months of travel were eight concrete, event-filled days on the ground in the District of Columbia and surrounding neighborhoods. Newspaper articles, photographs and documentary footage allow glimpses into the sights and sounds of the demonstration.

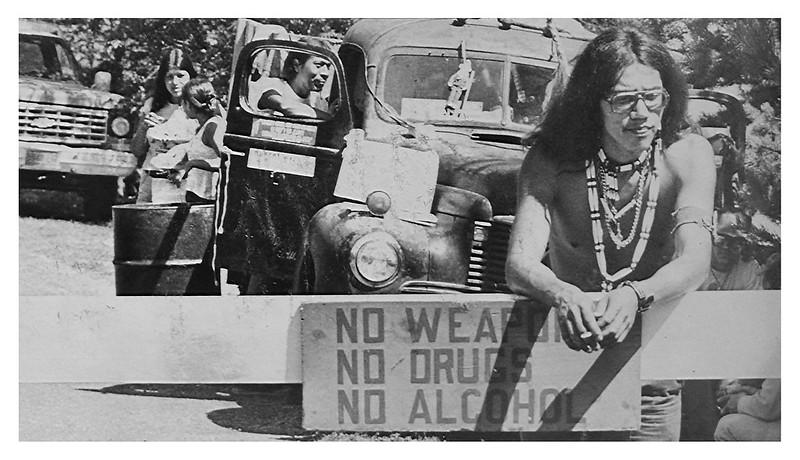

The march approached the District from the North, travelling along U.S. 29 from Patapsco Valley State Park outside of Baltimore to Silver Spring, before setting up camp in Greenbelt Park in Prince George’s County, Maryland.[4] Roughly 2,500 would stay in Greenbelt Park for the week; the Interior Department arranged for Metro buses to transport protestors ten miles to the heart of the Capital each day.[5]

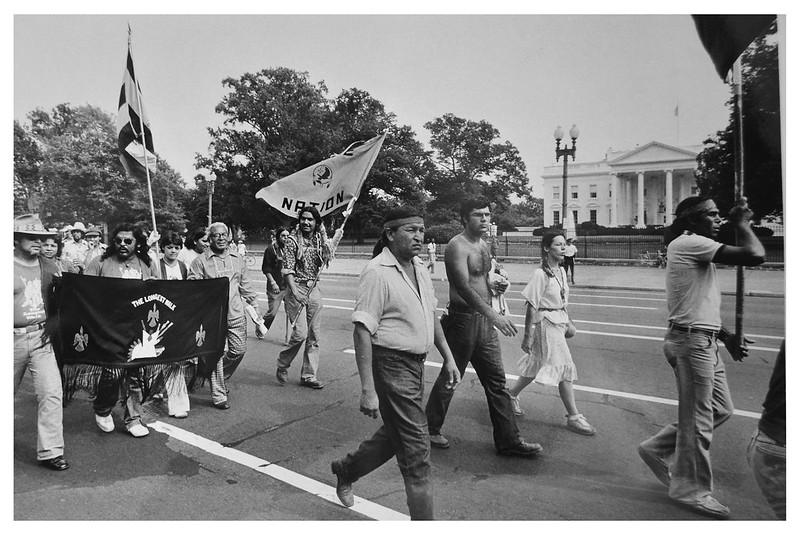

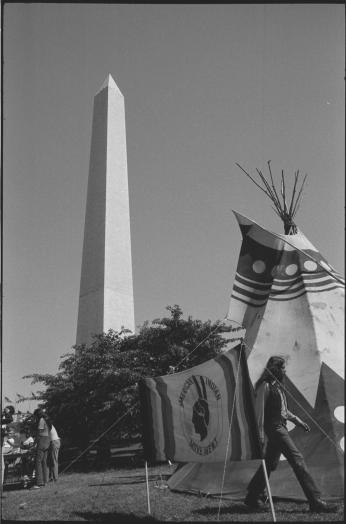

The demonstrators arrived in Washington on the sixteenth of July: the heat and humidity was (as you might expect) stifling. In an interview with The Sun, a participant named Red Cloud (Athapaskan) remarked, “It was hot, thirsty. I’m tired. I just want to get it over with. But we are united."[6] That same day, The Washington Post described: “Shepherded by police and Indian security guards, the cavalcade came down Georgia and Arkansas avenues and 16th Street NW into Meridian Hill Park (also known as Malcom X Park) for a midday rally before moving past the White House to the Washington Monument Grounds. ‘Welcome to Indian country,’ shouted Longest Walk leader Bill Means to a cheering crowd.”[7]

To many in Washington, the Native Americans’ methods appeared unconventional. In one Evening Star article, the authors remarked about how Park Police were surprised to find protestors picking up “each scrap of debris” after a rally in an effort to “respect mother earth.”[8] The Washington Post reported on conflicting ideologies between American Indian protestors and D.C. officials. As one British Columbian demonstrator (Carrier) put it: “The bureaucrat says the meeting will start at 2 p.m. and end at 4 p.m. We say the meeting will start when everyone gets there and end when everybody’s finished talking.”[9]

Notably, American Indian protestors did not walk alone, and were joined by Black, Chicanx and White allies, along with a group of Japanese Buddhist monks.[10] Multiple Black leaders and writers spoke about solidarity and sympathy with Native American causes. In Afro-American, a Baltimore publication, one writer editorialized: “As the weary, distraught, tired and sweaty band of Indians marched through the Washington Ghetto on the way to the White House, the watching Blacks must have shared the pain and hurt in their Red faces.”[11] Upon welcoming the march at the D.C. city line, Representative Ron Dellums of California said: “I thank you for not only dramatizing the history of oppression and genocide, broken promises and broken treaties of the Red people, but also dramatizing the oppressive conditions under which Blacks, Browns, Reds, Yellows, and militant Whites live in this country."[12]

Respectfully, event organizers asked White supporters to walk behind Native Americans and other groups of color to acknowledge the disproportionate discrimination faced by non-White people in the United States. Leaders said: “We do not wish to be insulting, but let our White brothers take up the rear.”[13]

In the subsequent days of protest, Longest Walk demonstrators presented the “Native American Manifesto” at a rally, marched on the White House and organized workshops at the monuments to educate about “treaty issues, sovereignty, energy development control, education for survival and other matters.” On July 23rd, the events concluded with a benefit concert at the D.C. Armory Starplex to raise funds for the protestors to go home.[14]

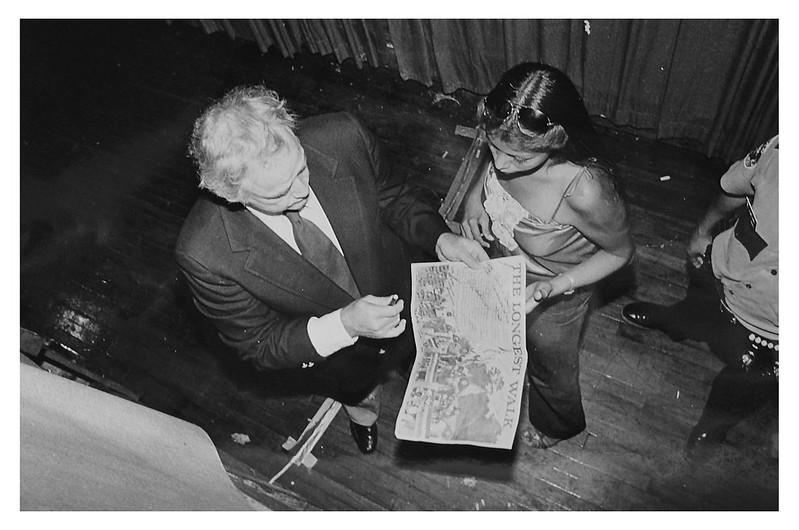

With tickets to the tune of $6, $10 and $25, eventgoers certainly got their money’s worth.[15] The benefit was star-studded. Flyers advertised performances by Buffy Sainte-Marie (Cree), Richie Haven, Floyd Red Crow Westerman (Dakota Sioux) and Dick Gregory. But, music and comedy weren’t the only things on the bill: heavyweight legend Muhammad Ali would also box a ten-round exhibition fight with a sparring partner. Marlon Brando and Stevie Wonder made guest appearances too, though it is unclear whether or not they also performed. In one legendary photograph, these performers are all gathered around a piano. The image is busy and candid, with every person looking in a different direction. Some are smiling, some present neutral, and others appear to be mid-sentence. The single frame speaks volumes about the energy and creativity behind the movement.

On many levels, the Longest Walk was a grand success. Congress did not pass any of the eleven bills, and the movement successfully spread word about American Indian issues to the American public.

As an Apache participant, Nasewytewa, said at a campfire gathering: “Now we have our own legends, like the first spark of a fire, but now the spark is a fire burning like a pine tree. We have power now. How are we going to use it the right way?”[16] As the first Longest Walk became legendary, it also became tradition: since 1978, there have been four others staged between 2008 and 2016 to raise awareness about environmental rites, sacred sites, diabetes, Native sovereignty, drug abuse and domestic violence. With measure, deliberation and thousands of steps, these marches have put Native American issues at the forefront where they cannot be ignored, demanding equity and justice for the country’s original inhabitants.

Footnotes

- ^ Naabahii Keediniihii,“The Longest Walk 1978_3,” Vimeo, August 2, 2013. Video, 3:08. Vimeo, https://vimeo.com/71600655.

- ^ “Native Americans Walk from San Francisco to Washington, D.C. for U.S. Civil Rights, 1978,” Global Nonviolent Action Database, Swarthmore College, https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/native-americans-walk-san-francisco-washington-dc-us-civil-rights-1978.

- ^ Naabahii Keediniihii,“The Longest Walk 1978_4,” Vimeo, August 30, 2013. Video. Vimeo, https://vimeo.com/73476953.

- ^ Paul W. Valentine Washington Post, Staff Writer. “Indians’ Walk Reaches Washington,” The Washington Post (1974-Current File), July 15, 1978, https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/146844632?accountid=46320.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Indians March on the Capital,” The Sun (1837-1994), July 16, 1978, https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/542165343?accountid=46320.

- ^ Paul W. Valentine and Patricia Camp Washington Post, Staff Writers. “Indians March into Capital,” The Washington Post (1974-Current File), July 16, 1978. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/146965476?accountid=46320.

- ^ Duncan Spencer and Rick MacArthur, “Indian Walk Ends; Protest Begins This Week,” Evening Star (Washington (DC), District of Columbia), July 16, 1978. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A13D5DA85AE05A305%40EANX-NB-14F40340A4DCBCB5%402443706-14F3F54DBA6DD382%400-14F3F54DBA6DD382%40.

- ^ Paul W. Valentine Washington Post, Staff Writer. “Indians Leave Baffled Bureaucrats,” The Washington Post (1974-Current File), July 24, 1978. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/146956847?accountid=46320.

- ^ Spencer and MacArthur, “Indian Walk Ends,” Evening Star.

- ^ Mark Hyman, “Indian Protest: Black Tears for Red Tears,” Afro-American (1893-1988), August 5, 1978, https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/532433900?accountid=46320.

- ^ Keediniihii, “The Longest Walk1978_Pt 3,” Vimeo.

- ^ Spencer and MacArthur, “Indian Walk Ends,” Evening Star.

- ^ “Activities Scheduled for Longest Walk,” The Washington Post (1974-Current File), July 17, 1978, https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/146812840?accountid=46320.

- ^ “A ‘Longest’ Benefit,” Evening Star (Washington (DC), District of Columbia), July 21, 1978. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A13D5DA85AE05A305%40EANX-NB-14E687CDD48A89FF%402443711-14E5700D65DA2814%4036-14E5700D65DA2814%40.

- ^ Brad Holt, “Ancient Rite Celebrates a New Legend – The Longest Walk,” Evening Star (Washington (DC), District of Columbia), July 19, 1978, NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A13D5DA85AE05A305%40EANX-NB-14F4035F76D9AB80%402443709-14F3F57048D579B2%4022-14F3F57048D579B2%40.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)