The Time Abraham Lincoln Argued a Case at the Supreme Court

For some lawyers, it’s the highlight of their career. For others, it doesn’t even make it onto their Wikipedia page.

The accomplishment? Arguing a case in front of the United States Supreme Court.

We’ve all heard about how William H. Taft became Chief Justice of the United States after he was President, but another President made a less well-known stop at the Highest Court in the Land on his way to the White House.

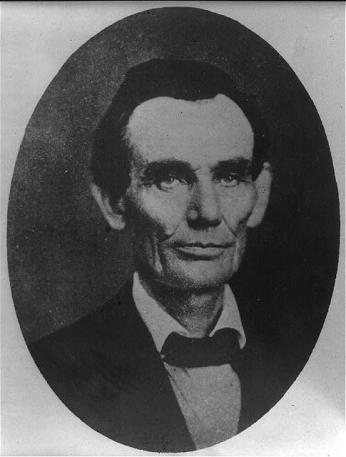

In 1849, Abraham Lincoln was wrapping up his first and only term as a Congressman. During his time in Congress, Lincoln was a member of the Whig party.[1]

Before Lincoln returned to Illinois, he got to experience the judicial branch of the federal government first-hand. On March 7 and 8, 1849, Lincoln argued on behalf of the defendant in the Supreme Court case Lewis v. Lewis, which was about the statute of limitations in relation to a contested land deed.[2] (Don’t worry, we won’t bore you with the details of 19th century Illinois state law.)

Lincoln was a self-taught lawyer, studying from books he borrowed from his future legal partner John T. Stuart.[3] In September 1836, Lincoln received his license to practice law in Illinois.[4] He was admitted into the Bar of the Supreme Court of the United States 13 years later — on the same day he argued the Lewis case.[5]

Honest Abe didn’t have to go far to make those arguments. The current Supreme Court building was not completed until 1935, and the court moved around a handful of times in its early years. From 1819 to 1860, the court heard arguments in the Old Supreme Court Chamber, which was in the basement of the Capitol.[6] So, Lincoln — who was nearing the end of his term in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1849 — only had to go downstairs from his day job. (Side note: Justice John Canton, “later blamed the dark, dank basement quarters for the bad health of many of the justices.”[7] But we digress…)

The oral arguments in Lewis v. Lewis lasted two days,[8] and Lincoln argued that the statute of limitations had expired, thus the plaintiff could not collect damages in the case.[9] He was only 40 years old at the time, but his preparations for the case have since been praised by legal scholars.

“The notes of Mr. Lincoln contain an accurate chronology of the relevant events, a clear statement of the issues, and a thorough canvass of the authorities which, while recognized to be not directly in point, were considered persuasively analogous,”[10] Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Arthur Krock[11] wrote in The New York Times in 1948.

Krock also added, “the text, according to the few who have inspected it, reveals Lincoln as a lawyer of great skill and competence, which some biographers have slighted and some have denied.”[12]

Despite his relative youth, in 1849, Lincoln’s “success as a trial lawyer was by then well established,” legal scholar James Simon wrote in 2011. “He spoke plainly and effectively to both juries and judges.”[13]

After the arguments, the court took just five days to render a verdict. Chief Justice Roger Taney wrote the majority opinion.[14] Lincoln lost the case.[15]

The case and its decision isn’t a particularly noteworthy moment in history, but it was the beginning of Lincoln’s adversarial relationship with Taney.

Born in Maryland in 1777, Taney succeeded Chief Justice John Marshall in 1836. Taney served as President Andrew Jackson’s Treasury Secretary, where he worked to help end the National Bank before Jackson nominated him to the High Court.[16]

In 1857, Taney wrote the majority opinion for the court in Dred Scott v. Sanford, the landmark case that considered whether Dred Scott, a Missouri slave who was bought by a new master and taken to live in the free state of Illinois and, later, the free territory of Wisconsin, had the right to sue for his freedom. The court decided that as a black man, Scott was not entitled to U.S. citizenship, and therefore did not have standing in the U.S. court system to sue.[17] As a candidate for Senate in 1858, Lincoln publicly disagreed with Taney’s decision.[18] (The short-lived Whig party dissolved in the 1850s,[19] and Lincoln was running as a Republican.)

On March 4, 1861, Taney gave Lincoln the Oath of Office, but during Lincoln’s time in the White House, the two continued to stand on different sides of the hot-button issues of the day, including the writ of habeas corpus and cargo seizures during a Civil War naval blockade.[20] Taney held his position as Chief Justice until he died in 1864, and he’s buried in St. John’s Cemetery in Frederick, MD.[21] On Dec. 6, 1864, Lincoln nominated his former Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase as Taney’s successor.[22]

In 1934, the Clerk of the Supreme Court, Charles R. Cropley, searched for other documents from Lewis but was only able to find the Court’s decision. Cropley believed the rest may have been destroyed in an 1898 fire.[23] So it was a nice surprise when Lincoln’s handwritten notes for the case surfaced after staying in his family for about 100 years. His son Robert held on to them, and after he died in 1926, his wife gave them to J. Spalding Flannery, a member of the District of Columbia Bar. Flannery then gave the papers to Chief Justice Fred Vinson in 1948, and they are now in the Supreme Court archives.[24]

Footnotes

- ^ “LINCOLN, Abraham | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives,” @USHouseHistory, 2013, https://history.house.gov/People/Detail/16982.

- ^ Lewis v. Lewis, 48 U.S. 776, 12 L. Ed. 909, 1849 U.S. LEXIS 372, 7 HOW 776 (Supreme Court of the United States March 13, 1849, Decided ).

- ^ Martha Neil, “Abe Lincoln’s Self-Study Route to Law Practice a Vanishing Option” (ABA Journal, January 22, 2008), https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/abe_lincolns_route_to_law_pract….

- ^ “Abraham Lincoln Legal Career Timeline,” www.abrahamlincolnonline.org, 2020, http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/education/lawhighlights.htm.

- ^ “Timeline | Articles and Essays | Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress | Digital Collections | Library of Congress,” The Library of Congress, 2015, https://www.loc.gov/collections/abraham-lincoln-papers/articles-and-ess….

- ^ “Building History,” www.supremecourt.gov, https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/buildinghistory.aspx.

- ^ JAMES F SIMON, “Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney,” Journal of Supreme Court History 35, no. 3 (2010): 225–42.

- ^ “Lincoln’s Oral Argument: Text of Notes for His Only Supreme Court Case,” American Bar Association Journal 34, no. 9 (1948): 791–828.

- ^ JAMES F SIMON, “Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney”

- ^ Arthur Krock, “Lincoln’s Clear Legal Mind Shown By Rare Text of His Notes in Suit,” The New York Times, February 12, 1948.

- ^ “Arthur Krock of The New York Times,” www.pulitzer.org, https://www.pulitzer.org/winners/arthur-krock-1.

- ^ Arthur Krock, “Lincoln’s Clear Legal Mind Shown By Rare Text of His Notes in Suit

- ^ JAMES F SIMON, “Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney”

- ^ Lewis v. Lewis, 48 U.S. 776, 12 L. Ed. 909, 1849 U.S. LEXIS 372, 7 HOW 776 (Supreme Court of the United States March 13, 1849, Decided ).

- ^ JAMES F SIMON, “Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney”

- ^ "Roger B. Taney." Oyez. https://www.oyez.org/justices/roger_b_taney.

- ^ Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393, 15 L. Ed. 691, 1856 U.S. LEXIS 472, 19 HOW 393 (Supreme Court of the United States March 5, 1857, Decided; December 1856 Term ).

- ^ JAMES F SIMON, “Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney”

- ^ “The End of the Party < The American Whig Party (1834-1856) - Hal Morris < 1801-1900 < Essays < American History From Revolution To Reconstruction and Beyond,” Let.rug.nl, 2012, http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/essays/1801-1900/the-american-whig-party/the-….

- ^ JAMES F SIMON, “Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney”

- ^ “History | St. John’s Cemetery - MD,” St.John’sCemetery-MD, https://www.stjohnscemetery-md.org/history.

- ^ “Salmon Portland Chase, 1864-1873,” supremecourthistory.org, https://supremecourthistory.org/timeline_salmonchase.html.

- ^ Arthur Krock, “Lincoln’s Clear Legal Mind Shown By Rare Text of His Notes in Suit”

- ^ “Lincoln’s Oral Argument: Text of Notes for His Only Supreme Court Case”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)