Charles Hamilton Houston and His Civil Rights Brain Trust

“The hate and scorn showered on us Negro officers by our fellow Americans convinced me there was no sense in my dying for a world ruled by them,” civil rights lawyer Charles Hamilton Houston reflected on his time serving as a Black officer in World War I.[1]

Houston’s experiences in the military served as the catalyst for dedicating his career to improving the conditions of life for Black Americans. A native son of the District, he transformed Howard University’s law school into a nationally recognized institution, built the foundation of the NAACP’s legal strategy, and empowered the parent activists of the District in their battle against school segregation.

My Battleground was America: Houston’s War Years

Houston did not volunteer for military service due to innate patriotism or belief in the war cause; rather, he served out of a sense of duty to his race.

“Woodrow Wilson’s appeal that America was in the war to save the world for democracy had left me absolutely cold because I knew that Black men had no place except as laborers in his scheme of things,” Houston wrote. He also believed Germany and other European powers were fighting the war for nothing more than “for a bigger share in the exploitation of the weaker peoples of the earth."[1]

“I was determined that if I lived, I was going to have something to say about how this country should be run and that meant sharing every risk the country was exposed to,” Houston continued, “My battleground was America, not France.”[1]

From training at Fort Des Moines in Iowa to serving in France and up until the moment they returned from their tours of duty, Houston and his fellow Black officers experienced this constant “hate and scorn” from their white counterparts, including almost being lynched by a crowd of white enlisted soldiers in Vannes, France.[2] On a train to the District from Philadelphia, a white passenger asked to be seated elsewhere after Houston and a fellow officer sat down. Houston wrote:

[We] were in officer’s uniforms with overseas service chevrons on our sleeves. I told the man we had just landed from overseas and asked him if he was going to leave the table because we were colored. He replied he could not help it if he was from the South. He moved...and I felt damned glad I had not lost my life fighting for this country.[3]

School for Social Engineers: Houston’s Howard Years

After serving in the war, Houston worked tirelessly to fulfill his goal of influencing “how this country should be run.” He studied law at Harvard and became the first Black staff member of the Harvard Law Review. Houston returned to the District to join his father in his law practice, and he moonlighted as a professor at Howard University School of Law’s evening school.

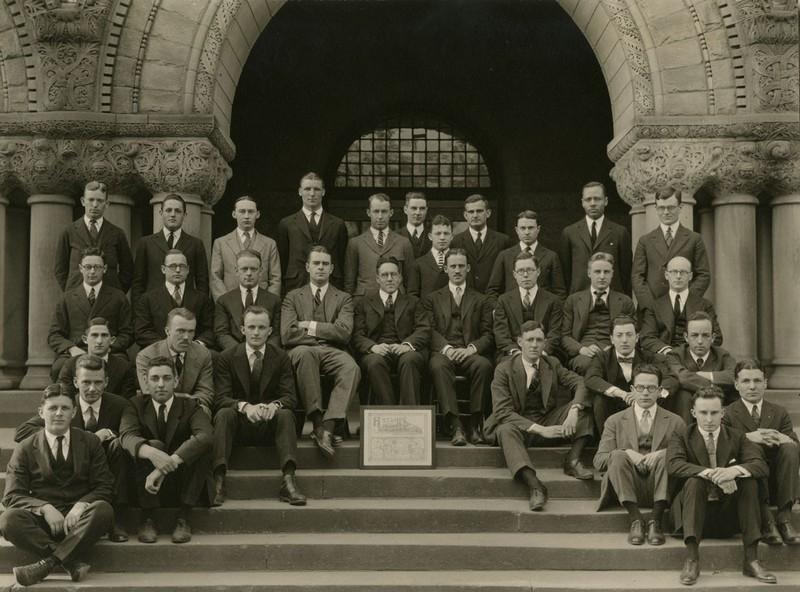

Houston soon became Vice Dean of the law school, and in this position, he was tasked with building up the law school into a world-class institution. This process would usually take a generation of work, but through Houston’s efforts, the law school was transformed into a nationally-recognized legal powerhouse and achieved accreditation by the American Bar Association within Houston’s five year tenure as Vice Dean.[4]

To meet the ABA’s standards, Houston ended the night school program. This was a controversial move as the program had afforded countless working class Black Americans, including Houston’s father, the opportunity to earn a law degree while maintaining full-time jobs. More than three-quarters of the nation’s nearly 1,000 practicing Black attorneys at the time had attended the Howard night school.[5]

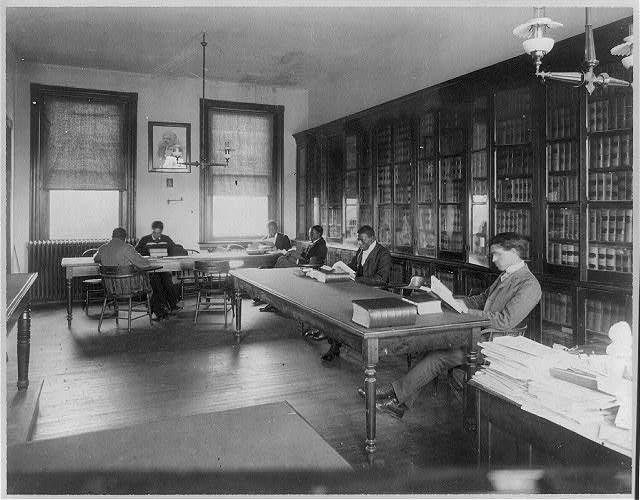

Houston compiled resources on race and segregation legal cases for the law library. Black lawyers from across the country sent in briefs, memos, and opinions from segregation cases in which they were involved. The law library became a “data bank on bias in America,” equipping the law students with the background knowledge they needed to take on the modern civil rights challenges. Houston also built a brain trust of Black legal talent at the university, recruiting lawyers like James Nabrit, who would eventually succeed Houston as head of the law school, to join the faculty.[6]

“[Houston] would dominate anything he was part of by sheer weight and activity of his mind. He did nothing with levity. His work was his only real interest in life, and he brought the full force of his personality to it,” Nabrit recalled of his tenacity and dedication.[6]

Houston also extended the length of the school year by several weeks, another unpopular decision especially among the students. Despite pushback from Howard alumni and others inside and outside of the university, Houston remained unrelenting in his work to raise the profile of the school and ensure the highest quality education. On several occasions, he turned down the promotion from Vice Dean to Dean of the law school, demanding the funds saved on his salary go toward those of the rest of the faculty.[7]

Houston’s goal for the law school was to train the next generation of civil rights lawyers because, as Houston explained, “experience has proved that the average white lawyer, especially in the South, cannot be relied upon to wage an uncompromising fight for equal rights for [Black people].”[8] Houston instilled in his pupils a belief in legal activism and that the law offers the “privilege of piloting the race in its persistent march toward full citizenship."[9]

“A lawyer’s either a social engineer or he’s a parasite on society,” Houston told his pupils. In Houston’s view, as “social engineers,” lawyers should use the legal system to expand the rights of underprivileged peoples. Social engineers were to be "the mouthpiece of the weak and a sentinel guarding against wrong.” Houston believed the legal system “enables [black people] to force reforms where they could have no chance through politics."[7]

A young student who graduated at the top of the 1933 Howard Law School class reflected on these lessons of social engineering taught by Houston, “He made it clear to all of us that when we were done, we were expected to go out and do something with our lives."[6] That student, the eventual Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, evidently did “go out and do something” with his life, fulfilling Houston’s desires for his pupils.

Marshall also reflected on how serious Houston was about his pupils’ education, “He was hard-crust...He was so tough we used to call him “Iron Shoes” and “Cement Pants” and a few other names that don’t bear repeating."[6]

Practicing What He Preaches: Houston’s Courtroom Years

Houston left the law school in 1935 to put his academic philosophy of social engineering into practice. He joined the NAACP as its first Special Counsel and enlisted other young, promising lawyers to join the legal team, including Thurgood Marshall, who would succeed him as Special Counsel. In this role, he developed the organization’s legal strategy to tear down the institutions of Jim Crow.

Houston held this role until 1940 and guided the NAACP through some of their earliest desegregation court cases. For this role, Houston has often been referred to as the architect of the civil rights movement’s legal fight.[4]

Given his deep connection to the District and his drive to end segregation, it is unsurprising that when Houston was approached by Gardner Bishop, the leader of the Consolidated Parent Group, about the school desegregation fight being waged in DC, the lawyer exultantly signed on as their counsel in 1947. “You’ve got yourself a lawyer!” Houston told Bishop.

Houston worked with the parents to litigate a series of four cases challenging the unequal conditions of white and Black schools in the District. He chose to pursue a strategy of equalization of the schools, instead of outright integration. It was believed by many civil rights lawyers of the time and some of the parents of the District that directly attacking the institution of school segregation would inevitably fail.[10]

Houston and Bishop became practically inseparable friends. “Charlie became part of us--a part of our group. I’d come by his place, and we’d sit up till three or four o’clock in the morning talking about everything,” Bishop recalled of his friendship.[11]

This unlikely duo of a nationally-recognized lawyer and a lower-class barber worked together to navigate the complicated legal and racial lines of the District. While the lawyer argued in courtrooms, the barber organized protests on the streets.[11]

Houston worked tirelessly to the point that his health began to suffer. He was hospitalized for a heart ailment at the end of 1949, and Houston’s father even blamed Bishop for overworking his son, bringing on this condition.[11]

Houston’s failing health took a toll on his barber friend too, and when the lawyer passed away in April 1950 at the age of 54, Bishop lost almost all of his motivation to continue the fight. However, before he died, Houston gave Bishop one last marching order, “"Go tell [George E.C.] Hayes and Jim Nabrit, they owe me and [to] take your case.”[10]

Footnotes

- a, b, c Houston, Charles H. "Saving the World for Democracy, Ninth Installment" The Pittsburgh Courier (1911-1950), Sep 14, 1940.

- ^ Houston, Charles H. "Saving the World for Democracy, Tenth Installment" The Pittsburgh Courier (1911-1950), Sep 21, 1940.

- ^ Houston, Charles H. "Saving the World for Democracy, Twelth Installment" The Pittsburgh Courier (1911-1950), Oct. 5, 1940.

- a, b "Charles Hamilton Houston" Howard University School of Law. http://law.howard.edu/brownat50/BrownBios/BioCharlesHHouston.html

- ^ McNeil, Genna Rae. "The Transformation of Howard University Law School" in Groundwork: Charles Hamilton Houston and the Struggle for Civil Rights. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984

- a, b, c, d Kluger, Richard. "Exhibit A" in Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

- a, b McNeil, Genna Rae. "“Dean” Houston’s School for Social Engineers" in Groundwork: Charles Hamilton Houston and the Struggle for Civil Rights. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984

- ^ Houston, Charles H. "The Need for Negro Lawyers." The Journal of Negro Education 4, no. 1 (1935): 49-52. Accessed March 25, 2021. doi:10.2307/2292085.

- ^ McNeil, Genna Rae. "Charles Hamilton Houston." National Black Law Journal 3, no. 2. [1973] Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/776794vd

- a, b McNeil, Genna Rae. "Community Initiative in the Desegregation of District of Columbia Schools, 1947-1954: A Brief Historical Overview of Consolidated Parent Group, Inc. Activities from Bishop to Bolling," Howard Law Journal 23, no. 1 (1980): 25-42

- a, b, c Kluger, Richard. "The Best Place to Attack" in Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

![This integrated classroom at Anacostia High School is the culmination of a seven year struggle against DC's segregated school system. [Source: LOC] Integrated classroom at Anacostia High School](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/AHS%20Class_0.jpg?itok=GNxSJFox)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)